When Janis Joplin left Austin for San Francisco in January of 1963, she didn’t immediately find the success and acceptance that she was hoping for. It had started promisingly enough; after hitching cross-country for three days straight, she and Chet Helms had gone straight to Coffee and Confusion, an old-style beat-folk coffee bar in North Beach that ran a ‘non-stop hootenanny’ at which performers were unpaid, and strictly forbidden from soliciting donations from the audience. But apparently Janis’s half-dozen country, blues and gospel tunes (sung a cappella bar the odd strum of her autoharp), got such a rapturous reception from the assembled folkniks that the proprietor broke with tradition for the first time, and allowed a hat to be passed. Depending on which source you believe, Janis earned anything from fourteen to sixty dollars that night.

The nearby Coffee Gallery became Janis’s regular haunt however, where she performed alongside other budding folk and blues musicians who would soon become mainstays of the California rock scene. After living in Texas the sense of freedom in San Francisco seemed intoxicating; it was more or less possible to get by without money, and Janis crashed in the basement of a communal house on Sacramento Street, salvaged discarded food from the street markets or the docks, and ate at church soup kitchens. You could dress as raggedy and weird as you wanted and nobody cared; if you sang or played music you were instantly accepted into this freewheeling community where ideas, energy and escaping the rat race were more important than ‘making it’ or worrying about the future.

These notions had existed in Austin too, of course, but in San Francisco there were so many more freaks, and there was a sense that they belonged to some kind of half-recognized bohemian tradition. Moreover this funky, sprawling city, facing west onto the great Pacific Ocean, somehow felt that much more open, optimistic and full of possibilities. In Austin, the hipster community was like the Alamo, heroically holding out while under siege by overwhelming opposition. In San Francisco, they felt more like pioneers, carving out a bold if precarious new lifestyle at the end of the western trail.

The west was still wild however, and San Francisco had its dangers, especially for a young woman as brazen, outspoken and unconventional as Janis. She was barred from the Coffee Gallery after she rejected the advances of a particularly influential player within the local folk scene, and was beaten up by a motorcycle gang after leaving a lesbian bar. She attracted some record company interest and the odd high profile gig, such as performing, unbilled, at the 1963 Monterey Folk Festival, but none of them came to anything, possibly because the San Francisco folk scene still preferred their female singers to be willowy, pure-voiced Joan Baez types, romantic pre-Raphaelite maidens in gossamer gowns.

Most damaging of all though was Janis’s predilection for hard liquor and shooting speed, bad habits which were condoned and even encouraged by the more extreme and edgy west coast bohemia she found herself in. She was drinking heavily from the moment she arrived, and at some point began injecting Methedrine, possibly when she spent the summer of 1964 in New York. Certainly not long after she got back she began dealing as well, and early in 1965 was so strung out, hallucinating and paranoid that she attempted to check herself into the San Francisco General Hospital as a mental patient. She was turned away, and began using heroin instead, as a way to numb the pain of the speed comedown.

In May 1965, mentally shattered, physically emaciated and at the end of her wits, Janis came home to Port Arthur. She came back not only to recover her health and her sanity, but also to get married. She had met a guy who seemed like a perfect romantic gentleman; handsome, smartly-dressed, well-mannered, charming and to all appearances absolutely besotted with her. Unfortunately he was also a sociopathic con artist and a compulsive liar, who was even more deeply into speed than Janis was; and he was already married.

While waiting for her bigamous fiancée to join her, Janis moved back in with her parents and made another of her periodic attempts to go straight. She stopped drinking, re-enrolled yet again at Lamar College, scraped her hair back into a bun and wore demure, conservative dresses, with long sleeves to hide the track marks on her arms. Eventually the fiancée turned up and duly charmed Seth and Dorothy Joplin, formally asking Seth for his daughter’s hand in marriage. But he did suggest they hold off publicly announcing the engagement until he had sorted out one or two minor details. He then split, never to return. For a while he stayed in touch, sending letters to Janis and her family and calling Janis on the phone. But when he failed to visit her over the Christmas holidays, everybody gradually began waking up to the fact that the wedding was off.

By this time Janis had tentatively started singing again. Though she initially avoided her old Austin crowd, she had kept in touch with friends from Port Arthur like local newspaper columnist Jim Langdon, who after many attempts convinced her to get up and sing at the Halfway House coffee bar in Beaumont at Thanksgiving. He gave her a respectful and encouraging write-up in his ‘Nightbeat’ column, and this led to a handful of low-key performances in Houston. In mid-December, not long after the 13th Floor Elevators had played their debut show at the Jade Room, Janis returned to Austin for a guest spot at the popular blues club, the Eleventh Door. Powell St John remembered seeing her set, and being shocked at how staid and prim she looked, like a school-mistress. Her voice however was intact, and more fierce and bluesy than ever.

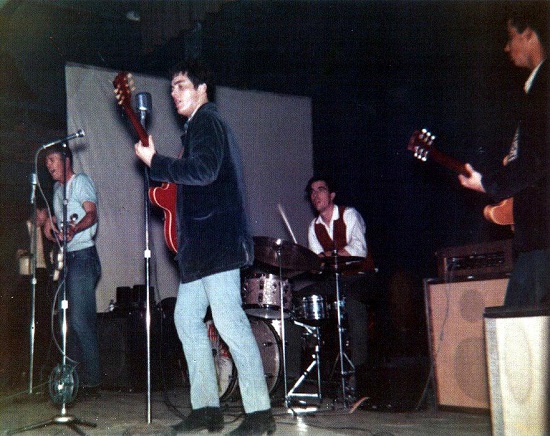

With Janis at the Eleventh Door, the 13th Floor Elevators at the New Orleans Club, the Wig at the Jade Rooms, St John and the Conqueroo at the IL Club and the Chelsea at the Fred, Austin in the early part of 1966 was starting to get lively. The different threads of the underground were starting to coalesce, as art students, rock n’ roll kids, beer-drinking cowboys and introspective peyote eaters all mixed and mingled, and country, blues and folk, rock n’ roll and R&B all went into the same pot. Collaborations naturally followed. Tommy Hall asked his close friend Powell St John to write some songs for the Elevators, knowing that he was an early initiate into peyote and LSD, as well as an experienced songwriter. Roky Erickson met Janis Joplin at a party, and Roky immortalised the moment in the line "I’ve seen your face before, I’ve known you all my life." He then gave this to Clementine Hall, who wrote the remaining lyrics for what became one of the 13th Floor Elevators’ best-loved songs, ‘Splash 1’.

The show that in most peoples’ memories really captures this sense of great potential beginning to bloom was a benefit concert for the blues musician Teodar Jackson at the Methodist Student Centre on March 12th 1966. Jackson was a blind fiddler from rural Gonzales County who often played alongside Mance Lipscomb; he had become seriously ill and was in urgent need of money to pay his medical bills. Tary Owens had become aware of Jackson’s plight while in the process of documenting local blues musicians on his reel-to-reel tape recorder, as part of his work as UT’s official folklore archivist. And though Jackson sadly died within two months of the benefit show, on May 1st at Austin’s Brackenridge Hospital at the age of 62, the funds raised did at least ensure his final days were relatively comfortable and dignified.

The concert featured the 13th Floor Elevators, Janis Joplin, organiser Tary Owens, Powell St John, Kenneth Threadgill, Bill Neely, John Clay, Mance Lipscomb and Robert Shaw. Despite being very much a blues event, the concert is also said to have featured Austin’s first psychedelic lightshow, created by future Vulcan Gas Company lighting genius Roger Baker using a bubble machine. In fact, Houston White’s Jomo Disaster lightshow were already active and had actually backed the Elevators at a show in Kerrville the previous night. Dressed in a severe black dress and accompanying herself on acoustic guitar, Janis sang the blues-folk standards ‘Codeine’, ‘Going Down To Brownsville’ and ‘I Ain’t Gotta Worry’, plus (according to some) Ray Charles’ ‘Drown In My Own Tears’ and as an encore her own composition ‘Turtle Blues’. Jim Langdon naturally described her set as the most exciting portion of the programme, and wrote that she "literally electrified her audience with her powerful, soul-searching blues presentation." This in a concert that he also noted "featured perhaps the finest package of blues talent ever assembled under any one roof in Austin."

The Elevators meanwhile arrived at the venue just before they were due to take the stage, and left immediately afterwards. Since they’d been busted they didn’t want to stick around anywhere long enough for the cops to catch on, and their sudden appearances and disappearances only furthered their enigmatic outlaw legend. However, Tommy Hall did arrive early enough to catch Janis’s set, and was impressed enough to ask her to consider joining the band as a second vocalist. Janis for her part watched the Elevators’ set and was equally impressed by Roky’s fiery, soulful hard rock singing, which many felt was a great influence upon her own subsequent style. Despite rumours though Janis never sang with the Elevators, and the possibility of her joining them as a second singer remained unfulfilled. It seems unlikely that Janis would have considered such a move at this stage anyway; she was still trying to go straight, terrified by the fact that she’d nearly destroyed herself with drugs in San Francisco. She was wary of the music scene as a whole because of the temptation of drugs, and with the notoriety of their recent bust still hanging over them and their open and continuous use of acid both onstage and off, the 13th Floor Elevators were surely the last group Janis would have considered joining.

Remaining resolutely on the folk-blues circuit, Janis continued to perform sporadically at the Eleventh Door club and elsewhere, including the Barrelhouse Blues Festival at the Union Auditorium on May 5th. As her health and confidence improved she began to loosen up and became more like her old self again. That month she quit college at Lemar and moved from Port Arthur to Austin, a sign that she was serious about resuming her singing career. However, at the end of that month she abruptly returned to San Francisco, this time for good.

Travis Rivers had come back from the West Coast with an open offer from Chet Helms for Janis to audition for a new band he was managing called Big Brother And The Holding Company. He convinced Janis that the heavy drug scene that had ensnared her before was all over, and that there was a new wave of electric folk-rock bands that she really needed to be a part of. Travis took her down to the Fred to see the Chelsea, who by then were playing a heavily blues-based set, closer to the band members’ true passions than British Invasion covers. Eventually Janis was won over. "Yes, that’s what I want to do," she admitted. She conveyed her decision to her closest friends; Jim Langdon, who wasn’t thrilled that she was walking out on her existing commitments, and Powell St John, who gave her a song he’d just written as a farewell gift. That song was ‘Bye Bye Baby’. Janis and Travis left in a car-load of freaks on May 30th.

Powell St John was also seriously thinking of quitting Austin. When the Elevators were initially arrested, many thought it was the prelude to the ‘big bust’ that would round up all the undesirables in town. Rumours of a mass arrest circulated every week, and such a plan was in fact being mooted by the police department. Powell was fully aware that his name was on the list and that he was under surveillance. He had noted how the police, the FBI and the University authorities had observed and harassed the Ghetto; now he was aware of an unmarked car following him everywhere he went. This encroaching atmosphere of doom and paranoia wasn’t helped by a beating he suffered at the hands of a group of rednecks around this time.

The final straw happened on the 1st of August 1966, with the notorious Whitman killings. Charles Whitman, a 25-year-old former engineering student and US marine, climbed to the top of the 307-foot university tower and began shooting students and citizens in the streets around the campus, seemingly at random. Armed with a sawn-off shotgun and a selection of high-powered rifles, his range extended to a quarter of a mile. He murdered sixteen people and wounded 32 others in the first mass shooting of its kind in America.

Powell had just finished rehearsing with the Conqueroo and had gone over to black East Austin to get a ticket for a James Brown concert that night. "Little did I know at the time that I was within range of this former Eagle Scout and marine sharpshooter," Powell told Terrascope, and in fact Whitman shot a cyclist who was riding down the same street. The good folk of Texas were advancing on the tower with deer rifles in hand, ready to take the assassin down; meanwhile, at the ticket outlet, a crowd of black Austinites gathered round the radio, waiting anxiously for the latest news on the shootings. They knew that if the sniper turned out to be black, their whole community would suffer reprisals. Powell for his part was equally fearful lest the killer turn out to have long hair and a beard.

"We were saved when it turned out that the guy was white and had a crew cut," Powell recalled. "About three weeks later I left Austin for Mexico, vowing never to return."

Ben Graham’s A Gathering Of Promises is available to buy here