“The creator of the new composition in the arts is an outlaw until he is a classic,” wrote Gertrude Stein. Lynne Tillman’s long out of print 1980 novella feels like a forbidden classic; the kind you spy on your parents’ shelf aged nine, read by torchlight under the covers and return with a frown and a tingle. Republished in 2015 by New Herring Press (a small indie press on the West Coast of the US), UK-based independent publishing house Peninsula Press has now brought Tillman’s compact and beguiling early work to UK readers.

Weird Fucks is a compelling, uneasy, and haunting ride through a series of encounters and relationships during the 70s, as the protagonist (the unnamed ‘I’) travels across Europe, London, and back to New York. It is a rollicking, at times almost diaristic and somewhat emotionally detached portrayal of a young woman’s formative years. Or rather, those years when you’re just figuring it all out, you know? Those years when you end up on a crappy date, stay even though things are clearly quite crappy and then have no idea what to do afterwards. Perhaps you leave, perhaps you sleep with them anyway, perhaps your diaphragm gets stuck and you have to embark on “a Herculean task never before recorded” to retrieve it in a communal hallway bathroom. Such is the privilege of freedom: the heady fallout of a 60s utopia. People go as quickly as they come in Weird Fucks, and when they go, and when it hurts that they have gone, ‘I’ turns to Valium and a Victorian nightgown and is on the move again. She is slippery, sometimes she is confused, and she is radical.

From exploring how much room women have to roam in both Haunted Houses (1987) and Motion Sickness (1991), to thinking about the effect of feminism on men born after the women’s movement in Men and Apparitions (2018) to her self-reflexive musings on art and culture through the character of Madam Realism, Tillman’s work – not least of all Weird Fucks, her first long manuscript over ten pages – often offers an uncompromising perspective on the evolution of Western feminism and against an essentialist stance towards the body and gender. When I spoke to Tillman about the book and its germination over the phone from London, I told her I wished I had read it sooner, wished it had been a companion to my twenties.

Reading Weird Fucks in 2021 holds a particular thrill, not only because of its nomadic quality, but because its stylistic verve – chapters cut close to the bone, rubbing up next to each other – is a reminder of how jagged our bodies can be, how easily we can miscommunicate and how silences can be a source of suffocation as well as power. A taut tease of a talisman, it lures you into rereading. “Part of my object in writing,” Tillman tells me, “is to find other ways to say things that strip language of some of its troubles or cultural attitudes.” And once stripped? I can’t help but think that freedom, like forgiveness, has its limits. Sex, like a sentence, is a performance and radicalism, like words, is weird. The consequences of revolution are never uncomplicated. It’s a wonder it was out of print for so long.

It is the 9th May 1960, and in the USA, the FDA has just approved the pill for contraceptive use rather than “severe menstrual disorders” alone. It is the birth of freedom. In his seminal lecture, ‘Two Concepts of Liberty,’ the philosopher Isaiah Berlin outlines two types of freedom: freedom ‘from’ and freedom ‘to’. “We may have had, we women, suddenly freedom from the risk of pregnancy, but then we had the freedom to… and do what? And that becomes another question.”

Lynne Tillman will spend a decade travelling across Europe after college, working in various experimental fields, reading and learning how to write. She is, for now, A Secret Writer, publishing anonymously, part of a film cooperative involved in structural film, part of “the sexual revolution,” she tells me, “and always a feminist from the age of eight.” She unlearns as much as she learns, reading Céline, Horace McCoy, the Bowleses. She was always reading. “It’s how I learned to write,” she says.

It is 1967, the Summer of Love. In England, London is prospering and people think it’s going to last forever. The mods are changing into kaftans, the underground magazines are making kids leave home and the hippies are the new aristocracy. Everyone believes the world is going to change. Former college lecturer and Ezra Pound fanatic William Levy is done with editing the underground paper International Times and is seeking new flesh, fresh words. A radical group coalesces – London, Amsterdam, New York – to bring, in the words of Willem de Ridder (the Dutch artist and early member of Fluxus) the intellectuals and the scene together on “this dangerous subject”: sex. Enter the complex soon to be superstar of feminism, Germaine Greer; founder of the London based alternative arts centre Arts Lab, Jim Haynes; poet Heathcote Williams and his supermodel girlfriend Jean Shrimpton. And so, in September of 1969, SUCK, the first European sex paper, an experiment in pantheistic freedom and expression (and ‘obscenity’) is born.

In Amsterdam, a refuge from UK obscenity laws, writer and translator Susan Janssen will join the gang as ‘Purple Susan’, as will editorial assistant ‘Dinah Armstrong’, aka: Lynne Tillman. Armstrong assumes the mantle of a restless housewife, arguing for the same sexual freedoms as men, arguing for whorehouses: “Women must revolt against the male tyranny.” In SUCK magazine’s fifth edition, Greer (‘Earth Rose’) will write, “Confrontation is political awareness […] we will have to generate enough energy in ourselves to create a pornography which will eradicate the traditional porn by sheer erotic power […] We must commission films, make films, write, act, cooperate for life’s sake.”

In the run up to the eighth and final issue, Greer will approach the photographer Keith Morris in London: “I want a close up of my cunt and you’re the only fucking photographer I can trust who won’t sell it.” The plan is for the whole editorial team to follow in their birthday suit(s), male and female – the body as a site of polemics; sex positivity as power. But it didn’t quite work out as intended. Greer is published somersaulting on the floor, legs akimbo, head pressed between. And if she is not entirely alone in this stance within the final issue of SUCK, she is alone with her very bright and visible, rather than distant and shadowy, arsehole. But then, Greer will always be the lone wolf, always out of step – the price of being a radical? Which kind?

SUCK was a social experiment, and just like that, by 1974, the experiment was dust.

In the 1970s, feminist writing was a feature of the public consciousness. In terms of the era’s expanding sexual freedoms and politics, British columnist Jill Tweedie – writing in the Guardian’s controversial ‘Women’s Page’ in 1975 (since 1922, the first feminist women’s pages on any newspaper) – called sex “that modern obsession”. Gender rules and the meaning of the body were being challenged (how is it supposed to act, what is it for). In amongst that challenge, sex was – in both the US and the UK – on the agenda of radical transformation.

Tillman returned to New York wanting to figure out a way to write differently about the sexual experience. “I think that [American curator and writer] Alison Gingeras sees it, and probably quite rightly, as my having developed this inclination from being around all of this pornography and sexual material,” she says now. “And it was basically dominated by the male editors, and one in particular, and they wanted to be open and inclusive of women and all of that, but… nonetheless I wasn’t finding my way. I wasn’t finding what I wanted to find with the work that was done there, far from it.”

Men had of course written about sex in a certain way for a long time, and when women were writing about it, it was, Tillman thought, in a way that had nothing to do with writing as writing. “It sounded very funky and awkward,” she says, “and not what I would think would be writing that would stand up to be read later – although who knows of course, I was much younger and I had thoughts like that.” It’s a desire that can be traced through to Eimear McBride’s Lesser Bohemians – sex as writing, rather than sex in writing – where McBride’s white gaps that punctuate the page (the characters’ synching breaths, leapfrogging sexual thoughts) are akin to Tillman’s structural frictions, glossed penetrations; language evoking sexual truth, or the truth of sexual emotion. Form as experience. Tillman recalls wanting Weird Fucks to be “very severe in a way, although sometimes I think some of the chapters […] are very funny or parts of them – but severe in the way it was written. I really wanted to avoid sentimentality for one […] it was so bold, you know, I was so determined … to be frank, severe, unsentimental, all of that.”

There is a separateness to the thirteen chapters in Weird Fucks that makes us question what it means to put the experiences that the ‘I’ has in proximity to each other. The reader needs to do the work of figuring out what they mean cumulatively, which is in part why the novella casts a certain thrall. The other is its near universal eliding of the sexual acts themselves – the brevity of their mentions often feeding the humour. The focus is rather on the precision of language. The concision of poetry has always interested Tillman, as well as the notion of finding the right word – not relying on a story in and of itself to be interesting, but in focusing on how it’s told.

Tillman’s archives at the Fayles Library in New York are a treasure chest for any fangirl. One early reader notes that its apparent glib toughness – a trait that places Weird Fucks in the urban American genre alongside Raymond Chandler and Dorothy Parker – belies its subtle changes of voice. The ‘I’ of Weird Fucks is a searchlight; not described by others, not (seemingly) desperate to be understood. She is “passionately uncaring,” easily disarmed, keeps “comforting men,” is cast as the “young thing who arrives in town and enters a world she doesn’t understand” until she realises that she has a taste for masochism and feels “trapped” by so-called “nice” men. On reading the manuscript, the American poet Paul Violi wrote to Tillman, “She’s got a warm heart and a cold eye.” Who is she? As Tillman has written, “We are all unreliable narrators.” It’s our secret justice.

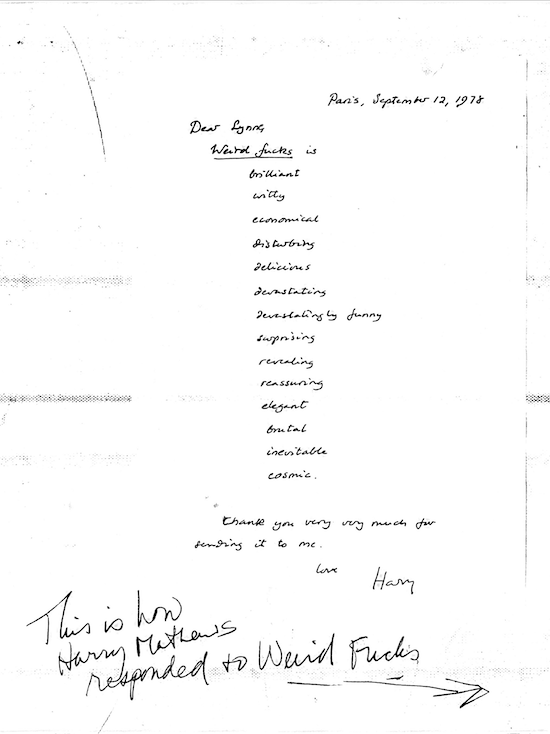

Letter from Harry Matthews, an early reader of the manuscript before publication, from The Lynne Tillman archives (Fales Library and Special Collections, New York)

Correspondence from publishers in the early 1980s, when the novella – or ‘novelette’ as one publisher wrote – was first sent out comment on its difficulty to place. Is it a collection of interrelated short stories, or an extended inventory or catalogue? It’s too short, there’s too much meat missing: who are these people, these men, really? Some note difficulty around publishing something with that title, “I mean, how could I give a book called Weird Fucks to my mother, no matter how good it is?” (Bill Zavatsky, SUN Press). Others advise adopting the more hardline punk collage style of Kathy Acker (a move into the more mutinous?) or of moving out of the “confessional” genre, in order to help its commercial viability – as if the ‘I’ is always oneself.

Yet there is another thread running through this early correspondence. One publisher asks to keep the manuscript a little longer, “I’m not sure why yet, but something about it bothers me, easy and bright as it is.” (Grand Street) Why? Lynne Tillman gets under your skin, makes you realise how strange skin is, makes you wonder at it, forces you to think of its malleability. “For reasons I don’t comprehend, Weird Fucks […] picked me up and sent me careening into a state of mind I last recall in my teens lurching drunk around Paris – aping Rimbaud my hero at that time.” (President and Owner of Thames and Hudson, Walter Neurath, February 1981). If Kathy Acker railed at the limitations of the word, fists to the sky, Tillman seems to survey it from a distance, plot its downfall in crisp chess moves, then head to the bar.

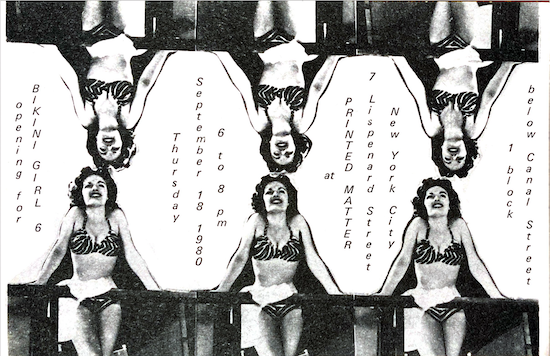

Weird Fucks first appeared in the US in the sixth issue (1980) of Lisa B.Falour’s (also known as Lisa Baumgardner) punk zine Bikini Girl (1978-1990), in such small print, it was a feat to read. The novella then appeared in Tillman’s first publication in the UK, in Serpent’s Tail’s Absence Makes the Heart (1990), and went largely unnoticed. It was only when New Herring Press published Weird Fucks as a book on its own in 2015, Tillman explains, that attention was paid to it. Announcement from The Lynne Tillman archives (Fales Library and Special Collections, New York)

Weird Fucks’ words mosh, anticipating punk. The sentences are slick, serpentine, and just when you think you have a hold on them, they slip away, like Houdini in a leather negligé: “A guy who hawked at a carnival wanted me to join the circus and run away with him. I was coming down from speed and learning to drink beer.” You become an ‘inmate’ to the pages. Inmate, this word, like many, rebounds, haunts. Like the figure of a mourning lover in a Victorian nightgown, soaked in Valium and numbed for two years, “I’m an inmate with a pass for the night”. I know this woman, I remember her. In-mate: insertions, exertions, interiors blinked at through a glass darkly. In-mate: lovers transition, sometimes into friends, sometimes they reappear (but on what terms?), often they just disappear through cajoling, ghosting or manipulation, “We knew you’d be back. You’re too smart for that.” Things seem in-evitable to the in-mate: “I hadn’t the slightest desire to fuck Tim but there seemed no way out. There was an inevitability about the night […] It was impossible to prove to him that I was not crazy.” Plus ça change?

With sexual freedom on the table, desire was on the front burner of feminist discourse in the 70s and 80s. Not just who you had sex with, but what kind were you having? “I think many of us women didn’t know what to do with that freedom,” Tillman says. “Did it now mean we should just fuck anyone, because we were free to do it? What were your reasons for saying no? […] You don’t know what to do with something if you haven’t really experienced it before, been allowed to play with it. And it was a very confusing time.”

So much so that, during the 80s, none of Tillman’s books, she recalls, were carried in feminist book stores, but rather in gay book stores. “I didn’t write positive female characters. Weird Fucks would not have been seen as helping the race!” She laughs. Lynne Tillman laughs often, a roasted marshmallow kind of laugh, a kind of laugh that says, ‘ask me what you need to ask me.’ Or at least this is what I tell myself. “The identity politics at that time was really about establishing positive role models, which is a terrible thing to foist on anybody, as if to try to exclude the flaws of any kind of human being – gay, black, woman, man, heterosexual, straight, un-gendered, whatever obviously. The idea that you have to create idealisations […] that was sort of going on in my work […] it just didn’t toe the line.”

In the late 80s, early 90s in the States you had the idea of ‘bad girls’ writing, and Tillman thought this was, well, bullshit. “You don’t want good girls or bad girls you want human beings,” she says. “They’re female, they’re male, they’re whatever they are. And so, what did they all write about? Sex. And that made them bad girls.”

One of the most open and curious writers, Tillman has always been dedicated to subverting expectations, always “at war with the obvious”, as she herself has written. Desirous to challenge or object to the way things have been written; to unshackle the body from a pre-determined role, from the idea that it is the foundation of everything. “I felt that the way in which girls lives and women’s lives were written, for the most part, ignored the incredible struggle that had to do with just becoming a girl,” she says, “how difficult it was to be a girl and to ‘become’ a woman. I just thought … that men had been portraying the struggle of manhood and becoming a man and all of this, but the idea that there was no struggle but childbirth was really horrible to me.”

My questions are thinly veiled yearnings. An overzealous schoolgirl caught up in the past, I have come seeking what it means to be radical now, why the striving for equality, for justice, is still so hard. “But you know with progress comes big problems,” Tillman tells me. “Everything goes so slowly, really, you know in terms of being able to take this in. And we’re not yet there.” Nothing is won forever.

I can’t help but recall Judith Butler who, writing in 2020, noted: “Feminism has always been committed to the proposition that the social meanings of what it is to be a man or a woman are not yet settled. We tell histories about what it meant to be a woman at a certain time and place, and we track the transformation of those categories over time.” Whilst some radical feminists of that era have mutated with the word into something more sinister in the UK (not seemingly the case in the US), Tillman has always maintained a progressive and empathetic mentality, seeking to loosen gender from its essentialist shackles. “I always feel that when I’m reading a good story or novel there’s something that’s being adjudicated,” she says. “That the writer is struggling with certain ideas, that in some very broad way have to do with justice – what is just, what is fair, how could this happen? Why is it going on?” Thinking about the ending of Weird Fucks now, Tillman is reminded a little of the end of a Chekhov story, where things that happened in the story will forever affect a future, where there are always consequences for things as they accumulate. “I mean no one gets off lightly, no one has all these experiences and just sort of dances into the night [she laughs] so I suppose that lets the reader know that this will affect her future life.”

Revolting has always been a tricky business, especially when it comes to women and the agency over their bodies. “The language has shifted and it has much less meaning,” Tillman says, “so when I called the birth control pill a radical thing I’m using it very deliberately, and it’s not appreciated for that. You know if you think of the millennia in which women were trying to control pregnancy and couldn’t… but of course anything that happens for women and to women would be less historically significant to men.”

In 2080, I hope Weird Fucks will get a centenary reissuing too. I hope it adorns teenage shelves in between now and then. I hope people will argue about its importance and its sexual politics and its spaces and how it goes down the throat like a jagged pill and how real world utopias were and are fleeting and vexed and incendiary and bliss and then agree that it’s missing the point. I hope I’m wrong. I hope it’s all figured out, less abstract, or maybe more so, but still tantalising. “I don’t – and I’m unusual in my age group I think in this respect – I don’t regret it,” Tillman insists. “I don’t regret even the anguish of having that freedom because I’d rather have it than not, you know?”

I can’t help but linger on Tillman’s choice title: weird as in wyrd, as in the fates, as in Macbeth’s weird sisters, those unearthly creatures. Wyrd women are prophetic. Weird women keep you on your toes. Wayward women keep you guessing. Whatever will they do next?

Weird Fucks by Lynne Tillman is published by Peninsula Press