“I like art where the blood is streaming and the flowers are blooming like hell.” – Peter Brötzmann

Pitiful royalties. Chronic ticket gouging. Shuttered venues. Charts clogged with nepo babies. Generative AI. Slashed arts funding. Brexit red tape. If you’re looking for signs that music is struggling, you hardly need 20/20 vision. Fortunately, that’s not the whole story.

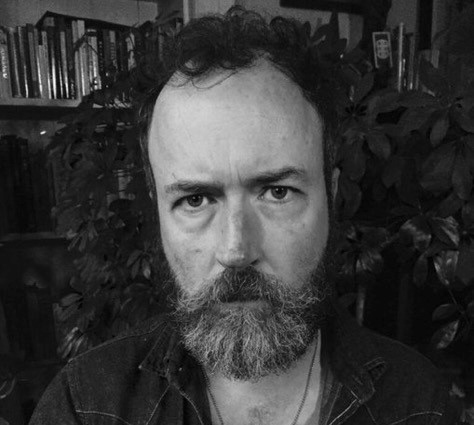

For music to survive all you need are two things: someone to make it and someone to take it seriously. In Scottish author and music critic, David Keenan, we have a writer dedicated to the serious business of music. I don’t mean business in the fiscal sense. Keenan’s interest in underground music has little to do with remuneration and just about everything to do with spirit. He knows that music is important. That art is a worthwhile venture. That igniting thoughts, feelings, and emotions in others is a pursuit far nobler than streaming figures and chart positions dare dream.

Keenan’s life altered irrevocably at the age of 17 after picking up and devouring the posthumous Lester Bangs collection Psychotic Reactions and Carburetor Dung. Here was a writer who wrestled with rock & roll like his life depended on it. And with Volcanic Tongue, Keenan has his own collected work, issued prehumously, that grapples with the output of sonic lifers. He does the work. He knows the players. He knows where they’ve come from and what and how they play. He writes in a way that makes you want to write. He makes you want to listen. When you read of AR & Machines’ Echo as “a classic of questing psychedelic Gnosis, with guitar spirals carved from nothing but afterimages of themselves and tracks that consist of huge billowing waveforms that vibrate like distant galaxies”, he makes you think that you have listened.

For Keenan language is a form of sorcery. “Letters are atomic,” he informed Stephen Pastel, adding that “words are magic, that sentences are incantations and that books are God-works in God’s shadow”. During the article that laid the foundations for his 2003 book England’s Hidden Reverse, he notes that “the core of the English Underground – Coil, Current 93, to a lesser degree Nurse With Wound – shares an obsession with esoterica and the occult.” It’s fitting then that Gnostic gnotions are streaked throughout Volcanic Tongue.

Keenan posits Jandek as “a glyph, a tarot card – the hanged man” following the musician’s confession that he likes to hang upside down. Bill Drummond’s approach is “intuitive magick”. Synaesthesia abounds with the likes of Faust, Peter Brötzmann, The Dead C, and Chip Chapman all seeking out sound’s “smell”. Brötzmann and Faust evoke Germany’s ghost as gasoline for creativity whilst Shirley Collins reminisces about ghost sheep encounters on the South Downs. And it’s through her eyes that Keenan treats the Second World War as a turning point in Britain, writing that “England woke from a dream within a dream.”

These aren’t the only apparitions haunting Keenan’s collection: Albert Ayler is repeatedly mentioned but rarely discussed. The main unspoken protagonist, however, is Keiji Haino. Haino joins the dots between Sonic Youth, John Fahey, Enka Music, Brötzmann (again), Faust (one more time), and Mayo Thompson. His spectre presides over the text like a storm cloud of ecstatic psychedelia striking an abundance of the book’s subjects. It’s particularly surprising as it was Keenan’s article on the Japanese guitarist that caught the eye of The Wire’s Tony Herrington. In an interview with Loud & Quiet Keenan explained that Herrington “left a message on my answer machine saying would I like to come and write for them. It was a dream come true; the next day I had to go in and meet Tony, and he never fucking turned up. But after that I wrote for The Wire for 25 years.”

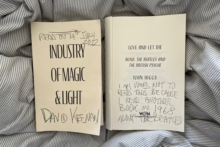

I first encountered Keenan, as have many, through his music writing. Specifically, his foray into the esoteric underground of England. Its hidden reverse. Of course, all of his writing is music writing, even if not labelled as such. His breakout novel This Is Memorial Device is the sort of book that all aspiring rock & roll critics imagine they should or could write. It blends the currency of niche knowledge with a libidinal swagger, mythmaking and, the energies best pronounced in Lester Bangs’ immortalisation of Peter Laughner: “I will not forget this kid killed himself for something torn t-shirts represented in the battle fires of his ripped emotions.” Its prequel Industry of Magic & Light, with its references to the likes of Fluxus, Impulse, and Avant Garde Italian composers, maintains the course.

Lester Bangs’ rousing words left an indelible mark on Keenan, lighting a touch paper for the sort of work that he could create. Glimpses of his private life bubble up through the sentences. A pivotal gig watching The Pastels in Glasgow with his larger-than-life father sets the tone. From there we take a trip with Keenan into New Weird America where paths cross with his now partner, “Texan pedal steel player and throat conjurer Heather Leigh Murray” who he describes as “tearing at the strings of her instrument with her bare hands, her eyes bobbing like pennies in her skull.” Then, later, a “vision in plasters and a gold-flecked 70s gown and scarf, she attacks the drums in a blur of sticks before breaking off into a series of moves that are half ghost dance, half Saturday Night Fever.” A year later Leigh had relocated to Glasgow and the pair opened the legendary record shop from which this book takes its name.

It’s a personal history. A life’s work spent investigating the life’s work of musicians. So, it’s their history too. In a 2014 feature, the notoriously elusive Jandek makes the assertion that he “led the boos when Dylan went electric at Newport in ’65.” Keenan rolls with Jandek’s imagery, picturing him Zelig-like throughout history: Jandek as Judas. Jandek as the lone gunman. Yet it is Keenan who we find time travelling. The annals of the 20th century’s lefthand musical path is viewed, more often than not, from the comfortable distance of the 21st. He slides through wormholes, utilising the advantage of time and distance to provide a lucid perspective. Investigating the artists within Volcanic Tongue will gift you an education and insight into worlds of not insignificant delight. In this way, it acts like Peel’s Christmas selections or the legendary Nurse With Wound list.

Be aware, however, that this collection is conspicuous in its absences. Hip-hop doesn’t get a mention. Nor do most forms of dance music. Keenan is speared solely by the soul of rock & roll and the myriad ways in which he sees it manifested. Be it in the snorting horns of David S. Ware, or Derek Bailey’s schizophrenic guitar work. Coil’s dancefloor dalliances aside, the closest Volcanic Tongue swerves in that direction is with his Hypnagogic Pop article in which he birthed a sort of proto-vaporwave genre that resulted in such an overzealous and reactionary backlash that I’m surprised he didn’t accessorise his usual dapper style with one of those chic neck support braces. The responses to that article hint at why he steered his craft away from those waters.

Volcanic Tongue is also a record of the music industry’s dilapidation and the spirit of resilience shown by those for whom the art matters much more than seeing their faces plastered on to a billboard. A prime example is Einstürzende Neubauten shifting their approach (what the industry would no doubt term “engagement pivoting”) during the creation of Perpetuum Mobile to allow their fans to watch the recording process via livestream. This form of invited surveillance punctured layers of mystique whilst allowing for a dialogue with and creative input from the band’s audience, as well as a little financial buoyancy.

Flicking further through Keenan’s pages, you’ll find Richard Branson meddling with Faust’s recordings, the mistreatment of Shirley Collins, and the un-minced words of Ben Chasny: “say ‘fuck you’ to complacency and people who think music doesn’t matter if it’s not being played on the radio, to say ‘fuck you’ to corporations who suck the magic out of life and music.”

Writing is a form of immortality. Or at least it’ll seem that way until every book is lost in the great server fires to come. These marks on a page leave a mark upon the world. Here the carnal language of rock & roll is translated, immortalised, sometimes even euthanised. Yet still Keenan feels and fuels that flame. It burns and surges, with ideas catching like wildfire in a headwind. His language dances up to the cliff edge, casting spells, and peering perilously over at the precipice of the world, just as these musicians cling heroically to their instruments, daring to glance down before pirouetting back towards the warm glow of safety. It’s enough to give you a little hope.