Viv Albertine as ‘D’ in Joanna Hogg’s ‘Exhibition’

Seen from one angle, Viv Albertine’s autobiography is an exhaustive inventory of masturbation, menstruation, crabs, childbirth and surgery that leaves the reader feeling more familiar with the contents of her knickers than the content of her head. It’s not a criticism, the fact that she’s chosen to frankly foreground what women are taught to keep respectably hidden. Albertine’s guileless, matter-of-fact writing style means that this memoir is both full-frontal and disarmingly discreet: sex is barely there and rarely prurient, while the body-horror of STIs, illness, fertility treatment and medical intervention is unflinchingly described in almost dissociative close-up. Her narrative is driven not by the childish desire to shock but the unwillingness to let self-consciousness dictate one’s self-expression. Both writer and reader are constantly made aware that being female is an exercise in self-consciousness-raising, that growing up a struggle to overcome it, and that growing-up is a process that many women may never really feel they’ve completed.

Carrie Brownstein, ex-Sleater-Kinney guitarist, has already nailed what’s great about Albertine’s recent solo career, in a review that’s quoted in the book itself:

If there is a voice in music that’s seldom heard, it’s that of a middle-aged woman singing about the trappings of motherhood, traditions and marriage… She places in front of you – serves you up – an image of the repressive side of domesticity, the stifling nature of the mundane, and turns every comfort and assumption you hold on its head. It raises questions that no one wants to ask a wife or mother, particularly one’s own… Because after a certain point, we’re supposed to feel settled, or at the very least resigned. [p.364]

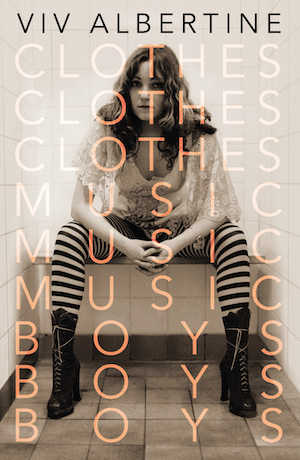

When describing Albertine’s journey to this point, Clothes Clothes Clothes, Music Music Music, Boys Boys Boys does exactly what it says on the tin. Her picaresque trek from truculent schoolgirl to artschool drifter to Slits ingénue to postpunk grande dame is tracked through her fascination with all three, and the notable clothes, music and boys of each significant period in her life are listed in condensed form at the book’s end in the manner of a teenage diary (or maybe just the manner of my teenage diary). But even if a woman’s life revolves around clothes, music and boys, they all introduce broader questions on how to live that life. How do you reconcile the domestic with the artistic? How do you deal with the gap between fairytale dreams and frequently nightmarish reality?

The Slits’ associate Don Letts has described 70s Britain as ‘the dark ages’ for women, a judgement which is brought home hard in Albertine’s recollections of her teens and twenties. In the debate around Savile and Harris and other still redacted names, we’re used to hearing the excuse that Times Were Different Back Then, but cultural mores aside, the world that Albertine depicts has young women routinely at risk of verbal harassment at best and physical or sexual assault at worse. When out at night, girls do not travel home alone on public transport, but the streets are equally volatile spaces: Albertine’s teenage bandmate Ari Up is knifed on two occasions by men who take exception to her outfit, and Viv herself spends her time dodging the fists, boots and rape threats of skinheads and Teds inbetween fending off the advances of friends, bosses, customers, travelling companions and chance encounters.

The Slits’ casually confrontational appearance and behaviour drew wildly negative reactions, but it’s hard not to see it as a logical response to a context where punk was making little headway against entrenched chauvinist and sexist attitudes which did not take women seriously, particularly as musicians. Part of Albertine’s initial vision for her all-girl band is: ‘I want boys to come and see us play and think I want to be part of that. Not They’re pretty or I want to fuck them but I want to be in that gang, in that band.’ Instead, the young Paul Weller, chatting at a party, considers letting her join his band as ‘crumpet’. Interviewers persistently question the band on their sex life. Managers ‘treat us like malleable objects to mould or fuck or make money out of’. Photographers and art directors attempt to shroud them in ‘sexy’ ripped pink plastic.

As Free Love and more freely available contraception made it harder for ‘liberated’ girls in the 60s to say no, so punk’s nihilistic and unsentimental perspectives, in which sex was viewed as emotionally meaningless, seems to have made its refusal harder for the women in Albertine’s scene: if sex meant so little, why not have it with any man who asks? At one point, she reflects: ‘we’re the children of the first wave of divorced parents from the 1950s, we’ve seen the domestic dream break down. It was impossible to live up to. We grew up during the ‘peace and love’ of the 1960s, only to discover that there are wars everywhere and love and romance is a con.’ In Albertine’s story, punk’s official jadedness and disdain for the body, sex, and relationships combines uncomfortably with the emotional intensity that grew between individuals in a close-knit scene. Viv exhibits a blasé innocence in her early sexual encounters, but in her on-off relationship with the Clash’s Mick Jones the desire for emotional stability, built on a ‘traditional’ relationship, is constantly in conflict with the expectations of punk: their attempts at a casual, open relationship lead to jealousy and possessiveness, Jones’ desire to protect her clashes with her fear of being made to look weak through reliance on a man. Not to mention the anxiety experienced over such un-punk acts as holding hands in public.

The space provided by punk for female emancipation can be overstated, but the Slits were unarguably, in the words of their contemporary Caroline Coon, ‘driving a coach and various guitars straight through… the concept of The Family and female domesticity’. In a context where young women were on one hand expected to supply sex on demand, and on the other violently reviled for falling short of conventional femininity, the Slits come across as necessarily radical, even if their shock tactics of self-expression may seem puerile or rudimentary to us now. Considering her own psychological battle against repressive female stereotypes, Viv admires Ari Up’s almost prelapsarian state of comfortableness with her body and its functions ‘in these times when girls are so uptight and secretive’ about both. Admittedly one might struggle to see Ari’s willingness to piss onstage, or the Slits’ on-air discussion of the stains left by menstrual blood, as a straightforwardly revolutionary act. But then again, one might also struggle with the concept that the treatment Albertine records from men throughout her life is either acceptable or inevitable. Like Germaine Greer’s advocacy of tasting one’s own menstrual blood, the Slits’ plain speaking on sex and sexuality, in an age where women were caught between sexploitation and slut-shaming, could be usefully subversive in its shockingness.

Beyond the sexual and emotional minefield, this memoir also captures the fun, compelling atmosphere, experimental then pioneering, in which bands like the Slits fell together and clicked creatively, writing, recording and performing in the febrile atmosphere of West London art-squats, Soho dives, and bohemian Chelsea. The Slits’ early music and performance was a squall of untrained, instinctive energy, challenging and disrupting ideas of what women – particularly women in bands – could and should be, and Viv draws strength and solidarity from the collectivism, collaboration, and mutual inspiration that marks her membership of the Slits’ sometimes dysfunctional family. The band’s aesthetic and behaviour onstage and off is frequently, and lazily, described in exoticising terms of wildness and ferocity – an analysis as recent as Simon Reynolds’ Rip It Up and Start Again in 2009 still introduces them as a ‘feral girl gang’ – but here the Slits come across as ordinary girls experimenting with the unprecedented free rein that punk handed them. Their eclectic backgrounds and musical tastes remind us that the Slits’ stuff was often more diverse than punk is traditionally thought to be, incorporating the dub, reggae and lovers’ rock in which their social scene was immersed. Their musical chemistry is shown as something natural and organic, but not necessarily ‘amateur’ (let’s leave ‘authentic’ out of it entirely).

If the Slits’ music was painstakingly pioneering, Albertine’s lyrical reference points could be surprisingly traditional: 50s-flavoured doomed romance and domesticity, vacant consumption, bad-boys and would-be housewives strung out on smack rather than Valium. Her life and emotions are often filtered through self-conscious iconography; exploring Newcastle with Subway Sect’s Rob Symmons, she muses: ‘It’s a dirty old town, just like Ewan MacColl’s song about Salford. ‘I feel like we’re in one of those sixties films, Saturday Night and Sunday Morning or A Kind of Loving’, says Rob’. Much later, embroiled in a vague flirtation with Vincent Gallo, she imagines herself in Badlands, or Bonnie & Clyde, or on the cover of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. Intriguingly, the times she doesn’t fall back on external artistic reference points are usually when describing the Slits, who are engaged in creating a new iconography of their own.

It makes sense that the end of a career like the Slits’ would leave one exhausted and in need of a break, and there is almost something post-traumatic in Albertine’s retreat behind domestic lines after the group stumble to a close in 1981. In ‘Side Two’, the book relates the untold and perhaps unsuspected adventures not of Viv the Slit but Viv the at-a-loss aerobics teacher, the mature student, the filmmaker, the estranged daughter, wife, and – eventually, gruellingly – mother. Exhausted, unsettled and ideologically out of step with the Thatcherite 80s, the mismatch between fantasy and reality is harshly restated as Viv doggedly searches for her knight in shining armour, but encounters only a dispiriting array of ‘nutters’ and ‘plonkers’ and, even when she thinks herself up to being emotionally adventurous or robust, her own body betrays her in excruciating ways.

She is also haunted by indecision over whether to opt for motherhood or a creative career. Although many punk and postpunk women moved into other fields after music – visual art, photography, writing – to continue their self-expression, for Albertine such experiments are fraught and prone to exasperation. She finds fulfilment in her work as a filmmaker, but then chooses to concentrate on marriage and housewifehood which, although initially agreeable, soon recede into an unsatisfactory backdrop, although she cannot quite galvanise herself into returning to art either. At a ceramics course in 2007, told to consider expressing herself in her work, she snaps: ‘I’m sick of expressing myself! I’ve expressed myself to death! I just want to make nice brown pots to put in the living room.’

Refusing to succumb to the pressures of physical and emotional fragility, Albertine movingly recounts the constant struggle to define herself and to be taken seriously, her unhappiness stemming from the kind of basic dissatisfaction which many feel but few feel able to express. More specifically, she finds herself still patronised, excluded, talked down to, accosted and assaulted, as though the gains of punk and their impact on her personally had never happened. As her marriage slowly and softly disintegrates, she realises: ‘It’s just like the fifties. If you are a full-time mother without a private income, you’re a chattel, a dependant.’ Throughout all this, she drifts. She deals with it. She attempts to preserve her integrity, and to survive.

Clothes Clothes Clothes, Music Music Music, Boys Boys Boys makes clear that none of these things define Viv Albertine. Nor does her time in the Slits, and, despite the opportunities it granted her, nor does punk – both are merely moments of inspiration in a life of inspired and inspiring moments. When she returns to music in 2008 as a provincial housewife, listless and loveless, battling through a local open-mic night, she is as incongruous, as rebellious, and as punk, as she was in the Slits. As Carrie Brownstein’s gig review acknowledges, the Slits offered a prototype for subsequent women in music, particularly riot grrrl, in both their music-making and their self-expression. As Albertine saw so many women as sources of inspiration and aspiration – from Yoko Ono, Patti Smith and The Avengers’ Emma Peel to her own mother and schoolfriends – so she finally derives some measure of self-validation by seeing that she has become a source of inspiration to others, not least her own daughter. Her memoir makes it possible to see how the radicalism that fuelled punk can extend throughout a woman’s life, allowing her to admit her discomfort with the role of girl-singer, girlfriend, groupie, wife, or mother, and to refuse to sacrifice her own happiness and integrity in order to shore up the crumbling pillars of feminine convention.

Clothes, Clothes, Clothes. Music, Music, Music. Boys, Boys, Boys. is out now, published by Faber & Faber