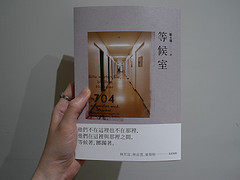

“I found this book in some bookstore. I had never heard of it before, nor had I ever heard of the author. I was attracted by the cover featuring a waiting room that looked like a hospital corridor. I started to leaf through it, and ended up reading the entire book in one ‘standing’ at the bookstore. It was easy to read and difficult to put down. I ended up buying the book even though I had finished reading it. I liked to copy favourite passages into my notebook, and as I copied her sentences I kept thinking to myself: if only I could have written these lines. I know what it’s like to be neither here nor there, to be in between, waiting for someone, or something.”

Michelle Wu first fell for <<等候室>> (Denghou shi) or The Waiting Room (2013) – Tsou Yung-shan’s highly visual and sensual novel about a Taiwanese migrant’s struggle to find his identity alone in Berlin – first as a reader and then as its translator. She’s currently pursuing the familiar labour of love of being the book’s ardent translator without yet having a publisher for it, but certainly has the right attitude: “At least I don’t have a deadline”. Though La Salle d’Attente is forthcoming with French publisher Piranha Edition, you won’t be able to buy The Waiting Room in a book shop any time soon, though Michelle is aiming to finish her translation this summer.

What’s the point of an article about a book you can’t read the whole of, you ask? Well, according to The Grayhawk Agency (the first literary agency to represent Taiwanese authors internationally) only one novel by a Taiwanese author has ever been published in English translation by a trade publisher: The Man with the Compound Eyes by Wu Ming-yi, published by Harvill Secker in the summer of 2013 and translated by Darryl Sterk. This means there’s not much of a chance to review Taiwanese literature in translation. It creates a kind of Catch 22: no book means no review, no review means no visibility, no visibility means no exposure leading to interest, no interest may mean even less chance of publishing, resulting in: no book. So: this one’s for all the great books yet to be translated.

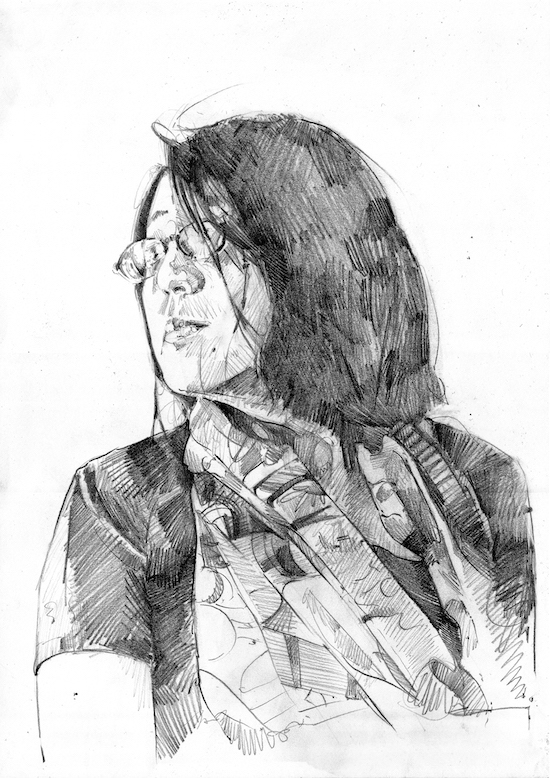

Tsou Yung-shan is one of many great writers profiled on Books from Taiwan – a new gatekeeper and grant-giver to contemporary Taiwanese literature and its translation into English – but stands out both for her engagement with globalised identities, and the way her writing has a European quality while viewing Europe from a beguiling external perspective. More rightly, she sits ‘between’ European and Taiwanese identities. A native speaker of Mandarin and Taiwanese, Tsou learned English and German in her twenties. Having first studied mechanical engineering in Taiwan, she decided to study a graduate degree in fine art in Berlin and relocated to Germany in 2001. She calls her visual work – which in turn influences her written work – Aufzeichnungen (the German for notes, records, documents) on inbetweenness, and can be considered more part of a nomadic literary tradition rather than necessarily in terms of a national one, or part of ‘world’ literature:

“I started the novel with a different kind of question: “What does ‘home’ mean?” instead of “Who am I?”

“In the globalised era, mankind’s situation is getting more complex. “I named this situation inbetweenness. The characters in the book remain ‘inbetween’, they are outsiders. As well as having existential identity as its more classical subject, social identity is defined in the book through bureaucratic processes. This alienation makes a person feel dissolved, detached and outside of himself. To present the absurdity of the bureaucratic system, I set important parts of the plot at the Foreign Affairs Office in Berlin; the Ausländerbehörde.”

Maria Meyer, who works at the Office, is central to the book through her own stagnated existence and also as designator of destinies to main protagonist Hsu Ming-chang, his Belarusian landlady and the Turkish-German artist Christina, who he befriends. The Waiting Room is not only the waiting room of the administration office, but the room Hsu Ming-chang rents, his state post-divorce, his ambiguous relationship with Christina (who, like Tsou, works in Aufzeichnungen), his creative development and his transforming sexuality, awakened by neighbour and graffiti artist Christian. As Darryl Sterk (translator of that one Taiwanese novel in English) states in his report on the book, it’s ultimately an inversion of the typical immigrant story in that Hsu Ming-chang successfully ‘makes it’ in his new home and is not overwhelmed by unfamiliarity.

Tsou shares a certain literary kinship with her favourite Taiwanese writer, pioneer of Chinese modernism Pai Hsien-yung. Pai wrote the semi-autobiographical ‘Death in Chicago’ and ‘Pleasantville’ in 1964, having moved from Taiwan to America to study the previous year. Both stories explore the alienation experienced by their Chinese protagonists in post-war America, and similarly The Waiting Room charts the limbo state and search for identity of a Taiwanese literary editor who has moved to Berlin, mirroring Tsou’s experiences. With The Waiting Room charting the fluctuating statuses of estrangement and connection experienced by its migrant protagonist, the process of translation is itself ironically similar with regard to Tsou’s pursuit for compromise and contentment as the book’s writer. There’s also the question of whether the reader is actually bypassing the ‘foreignness’ of the text completely:

‘I’m always very curious about how readers experience my written work without being confronted my own language. It’s a bit different from facing my visual work. The translation is a re-creation of my book by the translator, and I am not really able to influence her or his interpretation of my written work and I don’t want to, but I would like to have some kind of exchange with the mind of the translator if it’s possible.”

Tsou’s work is distinctly marked by her way of seeing as a visual artist, with writing being one method of mark-making and one more medium for intersemiotic transformation. Included among the writers she most admires is Georges Perec, the master of constrained writing, and similarly in Tsou’s visual work she sees the worth in creating distance between the reader and writing by bringing attention back to the word or character as ‘sign’ or ‘image’, or as an object for constructing an overall picture:

“In the calligraphy workshops I teach I’m most concerned with the image of the characters. First I explain the materials and tools, then the gesture of holding the brush, and how the stroke should look. The gesture decides the stroke, and having a proper physical relationship between the brush and the paper lets you have a stroke with a certain quality, which is the basis of the aesthetics of Chinese calligraphy. When a good stroke is done, then comes the composition of strokes and the subtle grey scale of the ink. The ‘set’ of strokes builds up the characters, and the black-white relations within or around the characters forms the whole image on the paper.

“I pay most attention to bronze inscriptions, which deliver the essence of the Chinese logographic system. I think the bronze inscriptions have a stunningly artistic quality, which hasn’t yet been revealed, and I think the quality has the possibility of being very contemporary. From researching them I try to build up a specific understanding of Chinese calligraphy. This process is somehow also a kind of translation.”

The physical book is part of the overall experience of reading and is a vital and irremovable part of the ‘novel’ for Tsou. Reading Tsou’s work in this online context really makes it a double translation: one interlingual, one textual/contextual/paratextual.

“When I make book objects, I also consider the interaction between the reader and the book. The physical relation between them influences the reading too. That’s why I think the materials, the book format, weight, the bookbinding can be part of the content.

“If physical expressions – sight, touch, sound, smell, even taste – were also considered a language, the set of the tracks of senses could be systemised as another kind of semiotics. The movement among the languages – spoken, written, painted, sketched, filmed – is for me translation too. The switch between media and materials is also a form of translation. Multiple languages widen the possible range of expression, and enrich the original ‘image’ when it’s re-documented, either in its own medium or ‘translated’ into another artistic form.”

from The Waiting Room by Tsou Yung-shan, translated from Chinese by Michelle Wu

00

It was 7:30 in the morning. He sat in the waiting room of the Ausländerbehörde—The Foreigners’ Registration Office—with his head bent. He didn’t read anything to kill time, nor did he bother to look around. Now and then people speaking different languages chitchatted around him, but he didn’t know what they were talking about most of the time. Once in a while, the sound of Chinese drifted down the corridor. In the past, he used to lift his head to follow the voices, but not anymore.

People waiting in the waiting room rarely conversed. Only those who came together talked to each other and they would talk about their common worries. Those who came alone usually sat alone with their own thoughts. Even though they were gathered in this room for the same purpose, they were all too tired to tell the strangers beside them anything about themselves. As the scattered conversations subsided, some closed their eyes for a brief moment of repose.

The sky was still dark when he was waiting in line outside the Ausländerbehörde. The quota for reservations had already been filled and those who had failed to make one in advance had to huddle up in a queue outside, in the dark, in minus ten degrees cold, until the guards opened the gate at 6:30. He had been there since 4:30 that morning and was lucky to have gotten a number. Those who had arrived thirty minutes after him were asked to leave because all the tags had been given out.

After a while, the sky slowly lit up. It was a gray and brittle winter morning. The skinny tree branches silhouetted against the window resembled pencil sketches on coarse, grayish paper. The little holes that punctured it were bird nests perching on branches. Further down the street huge sheets of translucent ice floated on the dark waters of the canal, resembling chunks of white paint showing through under the pencil markings. The cracks and fissures screeched and a lone goose perched on the ice flapped its wings and took flight.

The flashing red number on the screen beeped and the person seated beside him accidentally brushed his elbow when he stood up. The person apologized and he said not to worry. This was his first interaction with another human being in the waiting room. He shifted, cupping his chin with his hand, and tilted his head to count the nests in the tree. A bird had flown into the wrong nest. Finding that it was too small, it flew away. He followed the bird with his gaze, watching it fly over the canal and disappear into the buildings across the water. Inexplicably, his mood dampened.

It had been many years since he left Taiwan, that damp and rainy island. The climate in continental Europe was relatively dry and it didn’t rain non-stop like it did over there. When feeling blue, he often remembered the bone-chilling dampness that he experienced back home during the winters. He bowed his head to prevent the rain in his heart from welling up in his eyes. He bent his head low, so low that the pungent smell of the moist earth entered his nostrils, so low that the worms that had hibernated in the ground all winter could crawl up onto his hair. He was waiting and there would be no end to it.

He daren’t imagine an end to it. He looked down. He seemed to be staring at the number tag between his thumb and index finger, but really he wasn’t looking at anything at all.

Having bowed his head for so long, he felt a strain in his neck. So he looked up and stared straight ahead. Language schools had posted advertisements on the wall. ‘Come learn German’ was written in many different tongues. He stared. Finally the number that flashed on the screen was the same as the number in his hand.

He dragged his feet along the corridor flanked by offices. A map of the world was posted on the wall between doors. Colorful paper cut-outs Willkommen in Deutschland had been pasted on to the world map. He passed by the slogan, paused before the door of the office, knocked and went in.

[…]

02

After leaving the Ausländerbehörde, Hsu Ming-Chang tucked his collar in and wound his long, scruffy scarf around his neck several times. He sighed, emitting a puff of white smoke. He stood waiting by the bus stop, still thinking about what had happened between him and his wife and the incomprehensible events that had left these gaping holes in his heart. Yet, there was no going back. The forlorn feelings drifting through the holes in his heart were more pernicious than Berlin’s winters. No amount of heavy clothing could ward off the cold.

‘Don’t you have anything to say to me?’ she asked, before leaving him. She had already made up her mind regarding everything else. Hsu Ming-Chang didn’t see what there was left to discuss now. If this was how it was going to be, what more could he say?

In fact, he had a lot to say to her but none of it had anything to do with her decision or whether or not they had anything to negotiate. But he didn’t know where to start, so he didn’t say anything. This time, however, she didn’t wait indefinitely. She didn’t hang around, waiting. Before he knew what to do, she had left and he was left having said nothing at all.

She left. He stayed. Staying was unbearable and he grew fearful that somehow staying meant she could leave him again, and again he would be unable to find the words. The next day she returned, looked at him as if he were a stranger, waited for him to sign the divorce papers, told him to meet her at the lawyer’s office a few days later to straighten things out and then left. He allowed her to push him on and he barely remembered now what the lawyer had said to them. He then packed up his things, left the house that was leased in her name and boarded the night train to another city. His only moment of initiative. He chose Berlin.

Hsu Ming-Chang sat in a second-class carriage looking out the window with his chin propped in his hand. The train wasn’t moving very fast and he could see the tall straight birches flanking the railroad. The wind blew over the murky tips of the trees and a crescent moon hung in the inky blue sky. The train came to a halt for a while at Dresden. The eerie fluorescent light on the platform banished the dark, but accentuated the loneliness. Time seemed to come to a standstill. The sinking stillness weighed him down and he fell into a fuzzy dreamlike state, the images started moving again but there was no sound.

He fell asleep and then woke up. Morning had broken and the glow of sunrise spread across the rolling fields in the distance, an expanse of crimson red glowing under the deep blue sky. The colors of the sky turned a lighter shade and it became misty. By the time the morning fog had lifted, the train had arrived in Berlin.

He got off at Berlin Ostbahnhof, walked into train station and looked around. The morning sunlight had a grayish hue, so the train station, with its muted color scheme, also seemed gray. He had arrived too early and the stores were not yet open. People were few and far between. A janitor pushing his cart filled with cleaning utensils passed by, leaving two wet wheel tracks on the charcoal floor. His first impression of Berlin.

He waited until the stores opened and bought a map of the city. He checked his present location and that of his meeting later that afternoon and planned his route. He had found a sub-let in the classifieds and was going to see the room that afternoon. The apartment was located in Charlottenburg in the western part of Berlin. Hsu Ming-Chang didn’t want to drag his suitcase halfway across the city, so he left it in storage at the train station.

The S-Bahn was elevated so Hsu Ming-Chang could see buildings and scenery along the way. Berlin was much bigger than Munich, less refined and less orderly. His second impression of Berlin.

There had been a sudden downpour while he was on the train. Black storm clouds covered the sky. As the train entered the rainy zone, torrents of water splashed the windows and huge droplets moved in the opposite direction, leaving trails on the glass, blurring his view. By the time he reached the station, the rain had stopped and the sky was so blue that you would have no idea it had been pouring only a few minutes ago. The air after the rain was so refreshing that one gulp of it in your lungs made you feel as if you were made anew.

Charlottenburg houses resembled those of Munich. The atmosphere of the neighborhood also resembled the one he had left behind, and yet, there was an awkward feeling about the place that was difficult to describe. Hsu Ming-Chang stood on the ground floor with his bag looking for the name of the apartment’s occupant and, after some difficulty, found ‘Nesmeyanov.’ Ming-Chang waited downstairs until the time of the appointment and then rang the bell.

The landlady came downstairs to meet him. She was a solemn and hefty middle-aged woman. She didn’t look German. She showed him a room to the side of the apartment. The doors flanking the corridor were closed and the lights turned off, making it quite dark. When the landlady opened the door of the available room, Ming-Chang was welcomed by a bright and spacious feeling: the space was big with a tall window and French doors. Sunlight flooded the room, lighting up the dark corridor behind him. The French doors led to a tiny balcony offering an expansive view, from which he could count the chimneys of the neighborhood buildings. Hsu Ming-Chang made up his mind to rent it right away. The landlady looked at him with a solemn expression but, without much hesitation, told him he was welcome to move in.

They signed a contract, putting both at ease. The landlady invited Hsu Ming-Chang to sit down for a little chat to get to know each other a bit. She could barely speak English and Hsu Ming-Chang’s German wasn’t exactly fluent, so they had to resort to gestures and body language. Fortunately they managed to get through to each other without too many obstacles. The landlady’s name was Nesmeyanova and she had come to Berlin from Belarus with her husband. The couple had a son and the room for rent belonged to him. They found it difficult to pronounce each other’s names, giving up after several attempts. Hsu Ming-Chang summarily explained his occupation and was relieved to find that Mrs Nesmeyanova felt no need to ask too many more questions.

§

On the day that Hsu Ming-Chang moved into Mrs Nesmeyanova’s home, he only brought one suitcase with him. Everything he owned was in that suitcase. Dragging it behind him, he walked into the middle of the room. A mattress, a closet, a chair. Mrs Nesmeyanova glanced at his luggage and said if he didn’t mind, she would gladly provide him with a pillow and blanket. He accepted.

Having accepted the pillow and blanket, Hsu Ming-Chang went to put them on the mattress. It was then that he discovered he didn’t like the mattress being directly placed on the wooden floor. It was very thin and definitely not comfortable to lie on. Furthermore, when Mrs Nesmeyanova showed him around his room, she had kept her shoes on. It occurred to him when he moved in that the floors might not be clean. He took off one sock and walked around and found a layer of dirt had stuck to the base of his foot. He set the pillow and blanket down on the chair and asked Mrs Nesmeyanova to give him a cloth. He got down on to his knees and wiped the floors twice, including the area under the mattress. When he lifted it, he could hear small pieces of grit rolling onto the floor.

He put the mattress back in position, made his bed and burrowed into the blanket for his first night in an unfamiliar room. The pillow had a strong smell of laundry detergent, keeping him wide awake even though he was exhausted; the silvery moonlight shone into his room, landing on his blanket. He looked out the window and could see wisps of smoke from the chimneys against the moonlit sky. Though he had wiped the floor, there was still some dust caught between planks and his nose itched. The unfamiliarity of it all gave him insomnia. The next day, he cleaned his room again.

He ran into Mrs Nesmeyanova on his way to the bathroom to fetch water in a bucket. Worried, she asked him if he was comfortable in his room. Ming-Chang meant to reply that all was well and that he was not uncomfortable, but he blurted out ‘no’; in the German context, this meant that he was not comfortable and Mrs Nesmeyanova gave him an uneasy look before returning to the kitchen. She later kept quiet about his constant floor-wiping.

The floor no longer felt grainy when he walked barefoot. This made him feel much better. The days passed like falling sand. He wasn’t in the mood to decorate his room. He didn’t have a lot of possessions and settling in wouldn’t have been any trouble, he just had a vague feeling that he could leave this place any time, so his clothes stayed in his suitcase without making their way into the closet. A new place to live, but this didn’t necessarily translate into a new beginning. The room with one mattress, one closet, one chair, one suitcase, one pillow and one blanket that he couldn’t really call his own; none of it gave him the feeling that he could easily start anew.

Apart from wiping the floor every other day, he engaged in no other regular activity. He only left his room to eat, drink and to go to the bathroom. He stayed in his room all day without communicating with anyone. He read the novels from his suitcase, one after another. There were no curtains, so the sun shone directly into the room, illuminating the dust motes that floated in the air; the sun shone on his feet, then his abdomen and chest, then his face and into his eyes. He moved his chair around the room to avoid it.

On the balcony ledge were pots of herbs that Mrs Nesmeyanova had planted in the spring. When he moved in Mrs Nesmeyanova stopped taking care of them, so he watered them from time to time and when winter came, he moved the plants into his room to prevent them from freezing. When Mrs Nesmeyanova found out that he was looking after her plants, she gave him a bouquet of dried lavender as a token of her appreciation. Taken by surprise, he hesitated for a moment before accepting the lavender, discovering as he did so that Mrs Nesmeyanova had delicate hands. As he thanked her, he noticed that Mrs Nesmeyanova’s facial muscles, normally so tense, seemed relax a little.

He stroked the bouquet of dried lavender, releasing a heavy scent into the air. The room seemed to brighten up. He left half of the bouquet on the windowsill and tucked the other half into his suitcase.

Credit: Chapters O and 2 from The Waiting Room by Tsou Yung-shan, translated from the Chinese by Michelle M. Wu. © Michelle M. Wu. With permission from The Grayhawk Agency.

Tsou Yung-shan graduated from National Taiwan University before moving to Germany in 2001 to pursue a graduate degree in art, where she now lives and works as an artist. She won the Taoyuan Literature Prize in 2013, the Taipei Book Fair Foundation Sponsorship Prize 2013/14 and the National Museum of Taiwan Literature Sponsorship Prize 2013. She was one of four featured Taiwanese authors at the Taiwan Pavilion at Frankfurt Book Fair 2o14. Her debut novel The Waiting Room was published by Muses, Taiwan in 2013 and will be published in French by Piranha Edition in late 2015/early 2016.

Michelle M. Wu is assistant professor of professional practice in the foreign languages and literature department at National Taiwan University.

Jen Calleja is a writer, literary translator and musician based in London. Her short fiction, poetry, articles and reviews have been published by The Quietus, Structo, Huck and Modern Poetry in Translation, and she has translated prose and poetry from German for Bloomsbury, PEN International and the Goethe-Institut. She edits the Anglo-German arts journal Verfreundungseffekt. She plays in the bands Sauna Youth, Feature and Monotony.