When I’m reading a book, it’s my custom to turn to the acknowledgements first. In The Long-Player Goodbye, I noticed a lot of thank yous to record shops including my own favourite, Flashback on Essex Road in Islington. And of course a beautiful dedication to your better half (and occasional Quietus scribe) Emily. This made me wonder how much tolerance friends, loved ones and family members need to have towards you if you’re a record collector. It is more of a disease than a pastime isn’t it? My girlfriend is a record collector herself but has still had to put me on a strict one-in, one-out policy regarding vinyl recently, due to excessive browsing of the car boots . . .

Travis Elborough: "I am so glad you start there, it’s also something of a ritual of mine too. I also try to do the same with LP sleeve notes. There are some albums where I can hardly remember anything about the record itself but the acknowledgement remains lodged in my brain. I’ve got a Desmond Dekker LP from the late 1980s called the King of Ska, I think. I am buggered if I can recall any of the songs on it. Though I have a suspicion there may well be one called the ‘King of Ska’. I could just wander over to the rack and dig it out, of course, but that would spoil things. Because what I cherish about that LP now is simply knowing that there is a ‘thank you’ to the Wandsworth branch of the NatWest for lending him the money to record it, on the back cover.

"But, yes, I think you are right, record collecting certainly is a disease — or at least some kind of genetic malfunction. I am not especially convinced by a lot of the stuff put forward by biological determinists. But there’s always that moment when I first get through the front door with that day’s haul and catch myself in the mirror in the hall. And bam, there I am, a pool of Flashback, Haggle Vinyl and Help the Aged carrier bags at my feet and a sinking feeling that at least the ancestors might have dragged something back to the cave they could eat. Wear. Burn. Or hit someone over the head with, at very least. Don’t you think we also dignify the whole thing with that word ‘collector’? It’s a great way to justify the expenditure, isn’t it? Why do you have all these records? Oh, I collect them. It’s a bit like why do you need to drink four bottles of wine a night? Oh, I am oenophile. In my own case, while I was working on the book, I certainly felt able to justify virtually any record purchase — to myself, if perhaps not as convincingly to Emily — on the grounds that it was for ‘research.’"

Busman’s Holiday: Emily and Travis on the decks

Apart from buying loads of albums, what other research did you do before embarking on writing The Long-Player Goodbye?

TE: "Though it might not seem it, the book had quite a long gestation period. It was something I began to think about writing around the time the iPod first took off. I was struck by how quickly we had all got used to having so much more music, more easily, to hand. I vividly recall Nick Hornby appearing on Desert Island Discs in about 2001 and requesting an iPod as his luxury and thinking that undermined the whole point of the show. I’ve no particular beef with Hornby. But why go to the bother of selecting eight discs, if you are able to slip a lifetime’s worth of music onto the island anyway?

"So I just started to mull over the whole notion of musical formats, limitation, choice and so on. There were also some men who used to drink frighteningly strong lager in a park near where I live, and they seemed to spend most afternoons getting bombed out of their minds and listening to Fisherman’s Blues by the Waterboys on a portable cassette player. Only ever Fisherman’s Blues. And it made me wonder what on earth it would be like to just have the one, single album . . . Nothing else.

"By chance I also happened to come across a think piece in an old issue of High Fidelity magazine in the British Library, mourning the demise of the 78 record and complaining that the LP was putting too much music, too easily to hand. Which brought me up short — and sent me on a two-year-long rummage through whatever other hi fi mags were in the library’s collection.

"I also interviewed people like the record producer and field recordist Sam Charters, who told me about tracking Lightnin’ Hopkins down to a tenement in Houston. Hopkins had been out of action for a while and had previously only recorded on 78 — and it took Charters some time to convince Hopkins to play more than two songs for him for this new type of disc.

"And over the course of writing the book, it morphed in scope and size, quite a bit. I went to quite a few record fairs and interviewed punters and dealers but none of that stuff made into the finished book. Likewise, quite early on, I spent a very entertaining afternoon with Storm Thorgerson, the Hipgnosis sleeve designer, and a lot of what he said was really germane but somehow it didn’t quite fit in with narrative in the end, which became much more historical than I had originally envisioned.

"I hadn’t initially, for instance, intended to write that much about classical music. But, as I quickly discovered, the desire to stick complete a symphonic movement on one disc — rather than having it broken up on several four-minute-long 78s — was the chief motor in the development of the LP in the first place, so I had to make more room for that. I had no idea that, say, something that is as tiresomely ubiquitous as Vivaldi’s Four Seasons, was really a file-under-Bach footnote until the LP. And for much the same reasons — better clarity of sound, and an ability to hear it as a song cycle — it enjoyed such success again on CD."

Well, I don’t know about the oenophiles but enduring Fisherman’s Blues even a couple of times would be enough to persuade me to drink four bottles of wine in a sitting. What are the discs that you’re mad about — the albums you always have to get out when people come round the house?

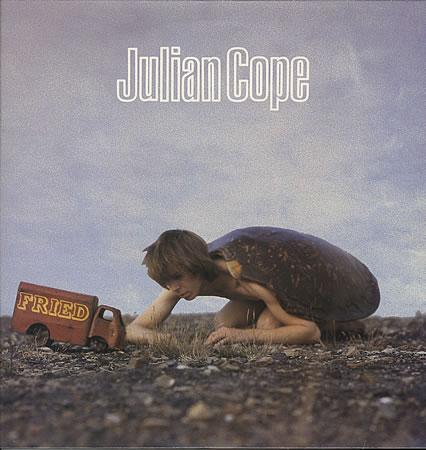

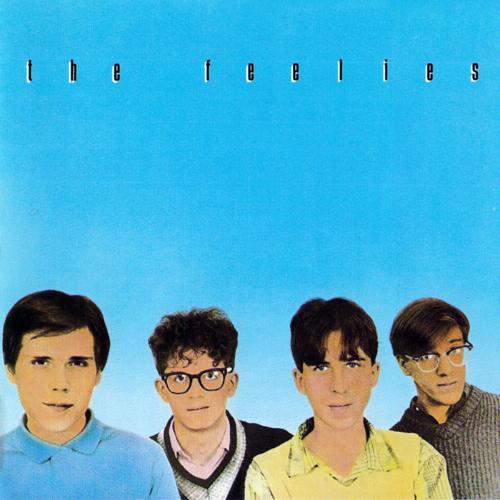

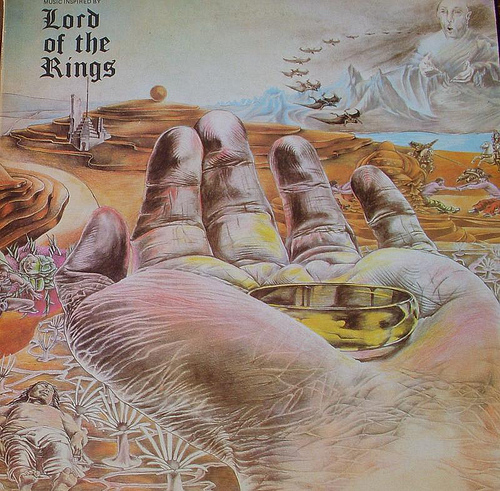

TE: "Currently the first Polyrock LP and the Feelies’ Crazy Rhythms are usually inflicted on most guests. That and Michel Legrand’s Brian’s Song Themes and Variations. And although I hate Tolkein, Bo Hansson’s Lord of the Rings album is also another staple. As is Julian Cope’s Fried."

A work of genius for ‘Sunspots’ alone . . .

What I found really interesting was how, in some senses, things are very much the same as they always have been. The war of formats between 78s and vinyl is similar to any other format debate I can remember whether that’s CD versus MP3 or CD versus vinyl or even VHS versus betamax.

TE: “Completely. Though the really interesting thing about the format war in the late Forties was that you not only had vinyl vs shellac 78s but you also had the so called ‘Battle of the Speeds’ between two new vinyl formats: RCA with their 45 RPM 7-inch and Columbia with their 10- and 12-inch 33 ⅓ RPM LP. As we know now, both of the new vinyl formats survived, killing off the 78. The 7-inch quickly going on to become the perfect medium for popular song and covetable by a newly-emerging generation of teenagers, and the LP helping to supply classical music, jazz, mood music, shows and films scores and so on to a mainly adult market. But it was a format war fought purely out of pique. David Sarnoff, the head of RCA at the time, was just pissed off that Columbia had managed to produce a workable, longer-playing vinyl record before they had. And RCA had tried to come up with something similar in 1930s without success. Rather than lose face and simply adopt Columbia’s technology, Sarnoff got his engineers to produce an entirely new rival vinyl record and then spent a fortune launching and promoting it. And it was a close run thing, after decades of 78s, consumers were suddenly faced with a profusion of formats. Record sales actually fell in the year after Columbia and RCA unleashed their respective vinyl records, and it was by no means certain that either would out the old speed and format."

It’s true isn’t it that so many leaps and bounds forwards in domestic comestibles can be traced back to the either the war or the military?

TE: Again, yes. Without the V-discs — a range of field-hardy polyvinyl records distributed as part of a scheme to supply allied troops with morale boosting music — it’s plausible that the vinyl LP as we know it would never have been born. And it’s really magnetic tape, finessed by the Nazis as a tool to aid propaganda broadcasts, that made the LP fully viable, allowing lengthier — and, importantly, editable — recordings to be undertaken."

Sadly, it appears to be true to say that the 40-minute album that people of our generation grew up with was solely about how much music could be fitted onto a disc rather than any aesthetic consideration. But at the end of the day isn’t there some kind of sublime ratio of music going on with the vinyl album, or am I just being sentimental? It feels like 40 minutes with a break in the middle is the right amount of time for an album whereas the 70 minute CD never did . . .

TE: "I don’t think you are being especially sentimental. I do personally think that the forty-odd-minute LP is/was an ideal length for an album. But it was entirely arbitrary and driven simply by the desire to put 90 per cent of the classical repertoire on two sides of a record — the technology was finessed with that aim in mind. As just over thirty years later the CD was designed, or so the mythology goes, to accommodate Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony — allegedly the head of Sony, or his wife’s or their dog’s, favourite piece of music.

"One of the most horrendous things the CD encouraged was prolixity. All those 25 track ‘Best Of’s and 70-minute albums.

"But it is quite extraordinary, really when you look back, just how long it took jazz, rock or pop musicians to really get their heads around even forty minutes of playing time back in the day. And personally I like the fact they often failed and resorted to filler. British pop, in particular, owes almost everything to the fact that the Chris Barber Band didn’t even have enough songs to fill up a 10-inch LP and that the group’s banjo player Lonnie Donegan plugged the gap with a couple of Skiffle numbers."

Isn’t the title of your book somewhat misleading given that in some quarters vinyl seems to be fighting a rearguard action against downloading?

TE: "Quite so, vinyl sales are indeed up. And as far as the album goes, it’s been telling that over the last few years that we’ve seen an increase in records — no matter what format they’ve been delivered on — whose raison d’être — or more crassly, selling point — is a conceptual theme or idea. Both are slightly rearguard, if perfectly reasonable, responses to way music is now largely consumed — in every sense of that word.

"I suspect that in the end convenience will out. I love vinyl — and there’s sixty years worth of the stuff out there for us all to enjoy and some great new things coming out on the format too — but in the book I make a couple of comparisons with photography. When I was growing up, my family probably took less than twenty photos a year, if that — and stuck the lot, regardless of how bad many of them were, into a cod-leather album. Now practically no single evening out goes by without someone taking twenty shots or whatever on their mobile phone. This glut tends to make any individual image seems less precious. But it’s hard to imagine any of us being able to go back to the days when you’d post your film off to Trueprint and wait two weeks for someone else’s snaps come back. And it’s the same with music. We all have access to so much more music via so many different means now. And we can’t unlearn that, no matter how much we might want to."

The paperback edition of Travis Elborough’s The Long-Player Goodbye: The Album from Vinyl to iPod and Back Again is published by Sceptre. He has another fine book in print called The Bus We Loved: London’s Affair With The Routemaster

The picture of Emily and Travis courtesy of Nick Tucker