There is a Henry Rollins stand-up routine, available on YouTube, which skewers a certain type of music fan a little too well. In it, Rollins is giving dating advice to his audience: don’t, he tells them in his characteristically emphatic terms, ever ask a woman her ‘top five’ anything. The answer might be terrible and it’s not worth it. Don’t ask what she’s reading at the moment; don’t — especial don’t — ask what the CDs are in her changer right now. ‘That,’ Rollins intones, ‘is that High Fidelity list shit’.

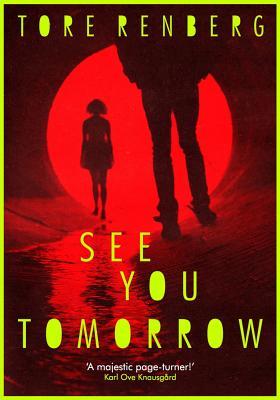

If there’s anything Tore Renberg’s novel See You Tomorrow is not, it’s ‘High Fidelity list shit’. Recently released by Arcadia Books in an English translation by Seán Kinsella, this is a novel soundtracked immaculately yet with little pretension. It is, to use a hackneyed phrase, profoundly down to earth; in contrast to both the recently popular Nordic Noir television series The Killing and Bla and the much-discussed novels of Renberg’s long-term friend Karl Ove Knausgård, See You Tomorrow deals with admittedly extraordinary circumstances in a deceptively straight-forward style. Literary and learned as Renberg undoubtedly is, the epigraph he selects for this novel is a Nick Cave lyric, and not an especially lyrical one:

Calling every boy and girl

Calling all around the world

Get ready for love!

It sets the tone perfectly for what’s to come: a fast-paced, polyvocal tale which races through its eleven characters with a rare fluidity. Although its structure is undoubtedly crafted with care, any fault lines between converging stories or, indeed, generic distinctions are ironed out. Its mixture of the exceptional and the everyday is perfectly proportioned: aspects of the novel seem utterly ordinary, but taken in its behemoth whole, it dazzles.

Presumably, Renberg’s ease in combining a multi-layered narrative with well-selected cultural references is a gift of his background. Known initially for his short stories — his debut collection Sovende Floke won the prestigious Tarjei Vesaas’ debutantpris — and subsequently for his works for screen, Renberg has also played in several bands, carving space in both the library and popular worlds. See You Tomorrow is as boundary-crossing as its author: defying easy genre designations, it centres around a crime story but tempers its grit with romance, humour and a generous dose of pop culture.

The novel opens with a portrait of fatherhood, as the troubled, debt-ridden Pål contemplates his dog (and his daughters), and closes with the impending motherhood of another character, Cecilie. In between these bookending depictions of the parent-child connection — arguably the relationship at the core of all interpersonal ones — Renberg undertakes a study of people and their bonds which somehow feels unassuming yet arresting at once. See You Tomorrow is not interested in looking too cool or clever, and as a consequence, it shines.

Its music is a case in point. Although the novel hangs heavy with references to films, television series and shops (a scarf from H&M gains some significance), its detritus is purposeful; rather than free-floating jetsam there for decoration, or to flatter a knowing audience, each cultural artefact is allied closely to a character. Popular culture is a means by which the cast of See You Tomorrow recognise themselves, and we in turn recognise them, as they become visible as much through their tastes and possessions as through words or actions.

Nowhere is this as obvious as in the novel’s music. Songs appear in the usual ways of fiction, as leitmotif or to signal a certain chronology, but they also serve as an emotional keystone. Music energises, comforts, forges identities; characters use conversations about bands to threaten, to negotiate, to intimidate or strengthen bonds. The bands in question are well-suited, too. In his jacket quotation for the book, Knausgård praises See You Tomorrow for its ‘pulsating passion for Balzac’, and there is something of the French novelist’s commitment to detail in Renberg’s musical reference. The novel is unflinching in its gaze; even when characters cite art which is, not to put too snobbish a point on it, fairly terrible.

It’s not unusual for a novelist to write morally ugly characters — to encourage empathy with well-meaning but faintly embarrassing ones is rarer. But See You Tomorrow lets nobody off the hook, and flies the flag for verisimilitude. The character of Tiril, a troubled teenager, has a love of Evanescence so deep it is hard not to cringe: having discovered their music on YouTube, we find her bemoaning the inconvenient number of letters in the band’s name, which prevents her writing their name across her knuckles in felt-tip á la ‘LOVE/HATE’ tattoos.

Later in the novel, two characters’ argument over the relative virtues of Coldplay and heavy metal music is not just a display of musical insight or inter-personal tension, but indicative of a deeper, more complicated fault line between their two personalities. The absence of pop culture, too, is meaningful: at the outset of the novel, when Pål realises how removed he has become from cultural life — ‘He’s not able to watch TV, he’s not able to read the papers, he can sit with a book in his hand reading the same page sixteen times over without grasping what’s written’ — it is immediately apparent that something has deeply unsettled him. Music in See You Tomorrow plays in people’s heads, triggers conversations, advances the plot; intimately intertwined with characters’ personalities in a way that is both vivid and mundane, it is as close to the music of Ulysses as High Fidelity.

Broader matters of identity are similarly finely-tuned. The characters consume international media — their music taste is almost exclusively Anglo-American — but pantomime, rather than absorb, other nationalities:

‘Cut that English crap out,’ he hears on the other end of the line.

‘It’s Americano, brother,’ he answers, laughing.

‘Whatever, it’s stupid, you’re from Norway, from Rogaland, from Stravanger, from Tjensvoll. Don’t put on an act ….’

For all their outward-looking vision, the cast of See You Tomorrow see elsewhere as filtered through pop rather than, say, international news or travel. The story’s criminals speak in a cinema inflected German which is half-sinister and half-playful. Their Norwegian town is the constant nexus of the tale, and the gravity exerted by one’s origins an inescapable force. When Tiril dreams of Evanescence she wishes she, too, could be from Little Rock, Arkansas.

With such weighty concerns, however, See You Tomorrow’s formal innovation remains impressively understated. Despite its length and complicated structure (it has, after all, eleven characters to represent) its form has a far more conventional feel than, say, Knausgård’s exhaustive project. There is a deft use of prosody in the different rhythmic footprints which accompany various characters’ moods, the impact of which in English owes much to Kinsella’s translation, but overall the novel’s third-person prose is refreshingly ordinary.

Structurally, See You Tomorrow’s most notable feature is the occasional chapter in a different style: one, for instance, is the transcript of a character’s private prayer, and another the dialogue of a phone conversation. But even these do not so much work against conventional narrative as display an irreverence towards traditional and self-consciously radical strategies alike. It commits to storytelling substance over literary style. It is a novel which shows human nature through bad taste and clumsy fun rather than careful scrutiny. It is inclusive, not exclusive. Made for every boy and girl, See You Tomorrow would never ask for your top five anything.

See You Tomorrow is out now, published by Arcadia Books. Photograph by Arne Bru Haug