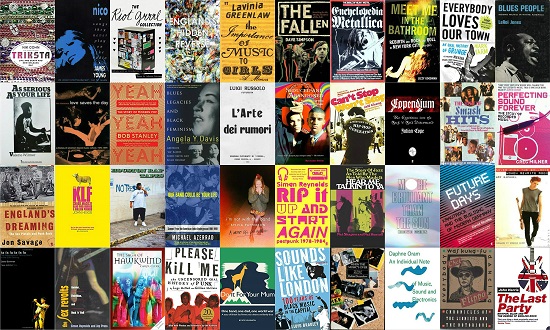

For this feature, we asked tQ’s esteemed contributors to select their favourite books about music. We’ve decided to omit straight-up memoirs (no Art Sex Music, unfortunately!) in favour of biographies, histories, compendiums and outsider explorations.

In response, we received a hefty list of brilliant works, writing on music from hip-hop to jazz, from krautrock to Britpop and from punk to dance. It’s a list of great variety, from Luigi Russolo’s early manifesto on The Art Of Noises to Lisa Darms’ tremendous riot grrrl compendium from a few years back.

There are some brilliant biographies too, like John Higgs’ extraordinary and sprawling delve into the mystical world of The KLF, and James Young’s irresistible warts-and-all story of Nico. We hope you enjoy this extensive delve into the finest of musical tomes.

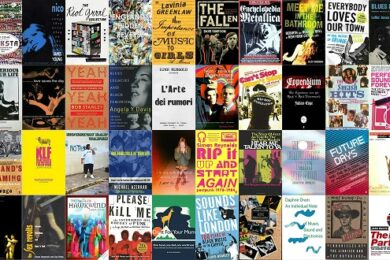

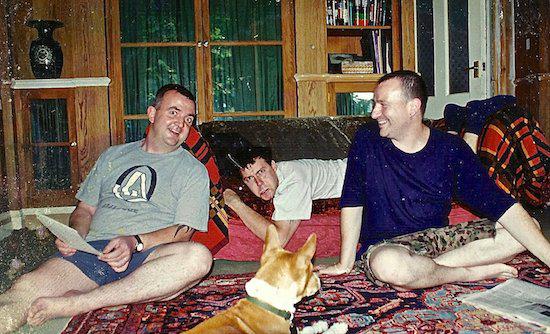

Love Saves The Day: A History Of American Dance Music Culture – Tim Lawrence (1994)

The Loft: picture courtesy of Duke University Press

From Tim Lawrence, lecturer in cultural studies at UEL, co-founder of the Lucky Cloud Sound System and author of the great Arthur Russell biography Hold On To Your Dreams, this is a thorough, academic, yet intimate account of disco in its nascent years in 70s New York and beyond. From David Mancuso’s humble beginnings, via the birth of the 12” single, to a point where we can look towards a culture ‘organized around pleasure rather than drudgery’, the book is a celebration of a definitive 10 years of dance culture.

Loft-style ‘parties’ are having a renaissance among a new generation for whom going out and dancing has been packaged up and sold to them at extortionate prices. Love Saves The Day is ever-relevant: an antidote to that commodification; a bible for those looking to facilitate nightlife with a similar ethos, or to forge that spiritual connection between the music and the dancers that bleeds from its pages.

Poppy Turner

Triksta: Life And Death And New Orleans Rap – Nik Cohn (2006)

Fifty years ago, Nik Cohn wrote Awopbopaloobop Alopbamboom, the first book on rock and roll. A few years later he wrote Tribal Rites Of The New Saturday Night, the New York Magazine story that Saturday Night Fever is based on. That’s already more than most music writers, even the really really good ones, will achieve in several lifetimes. Then, two or three decades later, he wrote Triksta.

In the four-page preface, Cohn really gives us the whole story: he’s loved New Orleans his whole life and then one hot afternoon, sick with hepatitis, enraged and a little deranged, he storms off – an ageing white bloke with a fat wallet – to the Iberville Projects. He’s duly surrounded by young black men, and he’s terrified. Later he realises something that makes him ashamed; “my deepest dread had not been of getting robbed or even shot,” he writes. “I’d been afraid of blackness itself.” He thinks of his life, “the posters on my wall, the records, all the black artifacts I thought were part of me.” And he doesn’t stop thinking, he doesn’t flinch. “What I saw in myself – the bloated sack of half-truths and jive – was something I couldn’t live with.” The next morning, he walks through New Orleans again. In the seventh ward a pickup truck goes past playing New Orleans bounce. Cohn follows it, and so do we. Where we end up is kind of unbelievable, and frequently heartbreaking, and this is never less than the best music book you’ve ever read.

Anna Wood

Nico, Songs They Never Play On The Radio – James Webb Young (1992)

Whether Nico would have thanked musician James Young for this devastatingly honest account of his time spent playing with the one-time Velvet Underground collaborator between the early 1980s until her death in 1988 is open to question. Nico fans, too, might sometimes have preferred it if he’d kept certain details to himself: he opens with a recollection of her shooting up in his Manchester bathroom, and his gaze remains relentless, shedding unflinching light on the reality of life as a fading, struggling icon. But Young’s book, which sometimes reads with the ease of a novel, is both intimate and sympathetic, a witty portrait of an enigmatic woman whose art usually kept her audience at arm’s length. Ostensibly a memoir built around tales of shabby tours of seedy venues and sessions with John Cale to record her final solo album, Camera Obscura, it allows Young to share the greater story of the German’s career, humanising her in a warts and all fashion that nonetheless pays tribute to her extraordinary, unique talent.

Wyndham Wallace

The Fallen: Life In and Out of Britain’s Most Insane Group – Dave Simpson (2008)

Steve Hanley was the longest-serving member of The Fall apart from Mark E. Smith and when I met him recently he expressed frustration with Dave Simpson’s book. You can see Hanley’s point. Despite their years of commitment to the Fall cause, he and his brother Paul appear in one short chapter whereas, as Hanley put it, you get pages and pages on some bloke who played bassoon for one gig. (For Hanley’s full perspective check out his own excellent memoir The Big Midweek.) Yet for your average Fall fan, and even those without anything approaching an encyclopaedic knowledge of Greater Manchester’s best ever band, The Fallen is a hoot.

As befitting The Fall, it is a fairly repetitive hoot and you’ve got to admire its chutzpah. There’s even a Melvillian Moby-Dick quality to Simpson’s normality-derailing obsession to track down every person who’s ever played in The Fall with the elusive drummer Karl Burns acting as Simpson’s own white whale. Will this mad quest destroy our beloved narrator? Not quite. It’s not about the whale; it’s about the journey. Or something.

J.R. Moores

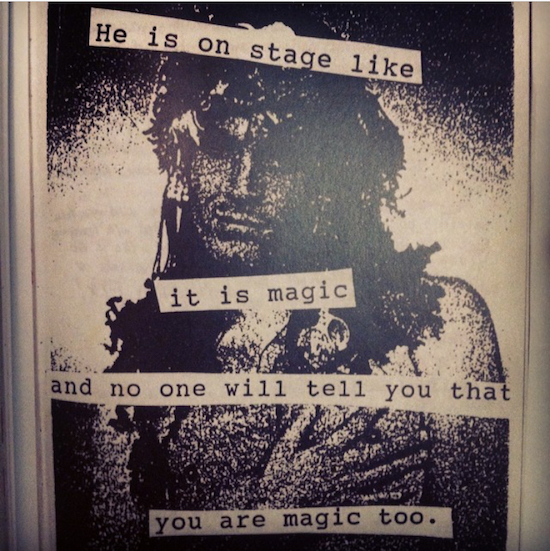

The Riot Grrrl Collection – ed. Lisa Darms (2013)

“Riot grrrl is the gateway drug that girls use to find feminist history,” says Kathleen Hanna of Bikini Kill. A complex, textured, messy, raging history unfolds in the DIY posters, zines, ripped out personal memos curated in Lisa Darms’ Riot Grrrl Collection. Darms, the archivist and founder at the IRL Riot Grrrl Collection at home in Fales Library, NYU, lived through the 90s cultural and music revolution in Olympia and experienced the era of cut-and-paste, gloriously angry feminism first-hand. In these pages lives a breathing, screaming manifesto, a movement captured at its stunning highs and deep lows: an original essay by Le Tigre’s Johanna Fateman, clippings of seminal zine Gunk, an open letter on harassment, an early 90s op-ed on the scene’s white feminism problem, and full-colour gig flyers.

It’s a message of liberation and cultural disruption that blew up the male-dominated punk scene, a movement pasted on one grrrl’s bedroom wall, and screamed into hazy, beer-bubbling air breathed in by another squashed happily against a speaker in front of a whirlwind four-piece. “Whatever riot grrrl became – a political movement, an avant-garde, or an ethos – it began as a zine,” Fateman writes. This is one for all the rebel girls.

Anna Cafolla

Yeah Yeah Yeah: The Story Of Modern Pop – Bob Stanley (2013)

A doorstop tome with the subtitle The Story Of Modern Pop that’s been penned by the bloke from Saint Etienne? It might not be top of the average tQ fan’s reading list. You prefer studying transgressive S&M performance artistes while listening to a mechanic in a thong who produces scratchy blastbeats using nothing but the most rudimentary analogue cassette machine and a collection of his victim’s hair, don’t you? As such, you’ll be delighted to discover that Stanley interprets pop music in what’s probably the widest and broadest possible sense, concentrating mostly on stuff that’s managed to slip its way into the charts, but even the really mad shit. Skiffle, doo wop, dub, glam, folk, prog, country & western, ska, mod, hardcore punk, metal, new wave, indie, rap, rave, techno, etc., etc., etc. The book’s breadth is astounding and its author’s insightfulness apparent from page one. By the end, this anti-rockist evangelist will have convinced you of many things including who is definitely best out of Patti Smith and Debbie Harry. (The winner is not the one clutching a well-worn copy of Rimbaud.)

JR Moores

England’s Hidden Reverse – David Keenan (2003)

Coil

For years England’s Hidden Reverse was something of a sacred texts among fans of the post-Throbbing Gristle quasi-‘industrial’ scene of Coil, Nurse With Wound and Current 93. First released by S A F Publishing in 2003, Hidden Reverse remained out of print, going for silly sums on eBay, before Strange Attractor’s repress in 2016. The music of Coil, especially, is surrounded in myth, hearsay and eye-watering Discogs resale prices – David Keenan’s narrative cuts through that to uncover a world of people pushing themselves as they pushed their music to stranger places. Unlike many who follow those groups, Keenan’s account is far from hagiographic, never failing to point out the dangers of extreme indulgence in drugs, magic, and over-enthusiasm for the art and aesthetics of Enid Blyton’s Noddy.

Luke Turner

Fa Fa Fa Fa Fa Fa: The Adventures of Talking Heads In The 20th Century – David Bowman (2002)

“Forming a rock group is an American mythic tradition”. With this, the first of a ceaseless torrent of switchblade-sharp epithets, author David Bowman takes the reader across a landscape populated with and scarred by that same mythos, conjuring his own in the process. Bowman’s keen, cumulative eye for the detail in the biographical makes the Talking Heads story read more like a surveillance report than a mere cultural diversion. The roads that led Byrne, Frantz, Harrison and Weymouth towards each other and their collective moniker Talking Heads are the launching pad for an incantatory cultural odyssey through an entire century’s creative methodologies – dada, cybernetics, performance art, oblique strategies – while leaving the purely sensational and the genuinely sordid resolutely on the record. It makes you want to watch Twyla Tharp dance, wallow in Bernie Worrell’s grooves, and listen to Jerry Harrison’s solo albums. No mean feat.

Kevin McCaighy

Blues Legacies And Black Feminism: Gertrude ‘Ma’ Rainey, Bessie Smith And Billie Holiday – Angela Y. Davis (1999)

Ma Rainey

Davis’ 1999 text, Blues Legacies and Black Feminism, is a thorough and contextualised dissection of the blues tradition, looking into the cultural consequences of post-slavery and segregation through the lives of the genre’s matriarchs – Gertrude ‘Ma’ Rainey, Bessie Smith and Billie Holiday. One of the book’s most interesting takes is the acknowledgement of the overt sexuality in the lyrics of the early Blues, and how this is a reaction on the part of African-American woman to the hyper-feminine values of the early 20th-century American middle class.

Black women were the first to sing the blues, yet at the time reaped meagre benefits in terms of both finance and recognition, having their standing usurped by black men, and then white men and women. In producing this intellectually feminist text, Davis provides an indispensable analysis of the social, political and historical influence on the blues, and how this in turn led three undervalued women of colour to inspire the blueprint for American, and thus global, popular music.

Olamiju Fajemisin

England’s Dreaming – Jon Savage (1991)

For this writer, Jon Savage’s history of the Sex Pistols and the first wave of punk rock is, quite simply, the greatest book written about popular music and youth culture.

This weighty tome benefits from a number of crucial factors, chief among them is Savage’s ability to prioritise context and historical data over mythology and hyperbole. It still beggars belief now as it did then that the Britain of the 70s was a country still recovering from the ravages of the Second World War. The economic boom of the 60s and its accompanying social mobility was over and in its place was a country blighted by economic strife, political uncertainty, racism and the feeling that the nation was headed for the rocks. Sound familiar?

It’s against this backdrop that Savage tells the tale of a youth cult that had to happen. Factor in fashion, a history of pop culture, radical philosophies and a desire to simply have fun whilst finding meaning, England’s Dreaming is exhaustively researched whilst never being an exhaustive read.

Julian Marszalek

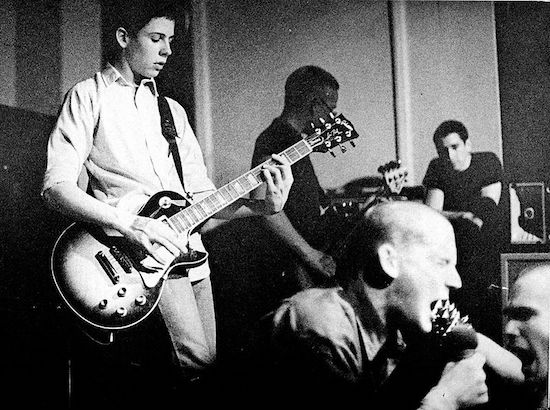

Our Band Could Be Your Life: Scenes From The American Indie Underground, 1981-1991 – Michael Azerrad (2001)

Minor Threat

Azerrad’s 2001 history of Amerindie offers 13 potted biographies of bands who represent a crucial, overlooked decade in American rock. It rakes over a fertile patch of pre-grunge history with roots in Reagan-era economics that yields bands like Black Flag and Hüsker Dü, labels like SST and Touch & Go, characters like Beat Happening’s Calvin Johnson and Minutemen’s D Boon, whose stories play out in cities and towns across America, in close-knit yet interdependent communities. The emphasis here is on stories and characters rather than a unifying sound. Like many great music books, it’s not really about the music at all.

Azerrad (also the author of 1993’s Come As You Are: The Story Of Nirvana) relishes the detail of the DIY lifestyle, one that as Ian MacKaye (Fugazi, Minor Threat) points out with characteristic Zenlike focus, takes a lot of doing. Standing out amid all the get-in-the-van guts-slogging, Mission of Burma’s first national tour takes in 11 cities in 22 days via a United Airlines offer that means they have to fly everywhere via Atlanta, including Seattle to San Francisco. While Greg Ginn’s proud dad goes to teach at Los Angeles’ Harbor College in shirts with the Black Flag bars in marker pen on the pocket. There lies the essence of this book; love and true dedication. How even amid the worst social and political dissolution remains the possibility of reintegration by music, the communion that preserves the human spirit.

Jenny Bulley

The KLF: Chaos, Magic And The Band Who Burned A Million Pounds – John Higgs (2013)

John Higgs is a brilliant writer; able to weave wild digressions into a cohesive central thesis, to veer off into the wilderness and still somehow end up in the right place. Everything he writes is approached from an oblique angle and yet his intuitive, synaptic connections never seem forced or laboured.

This is ostensibly a book about the KLF and their 1994 money-burning. But there’s nothing so linear as biography here unless it’s a biography of ideas. Instead, this is a book about magic, myth-making and miracles. It’s also a journey through time and timelessness – to read it is to imagine that The KLF existed before Bill Drummond and Jimmy Cauty were born and will outlive them too, possibly by millennia.

Because as Drummond, Cauty and the various mischief-makers who preceded them (Robert Anton Wilson, Ken Campbell, Alan Moore, a demonic rabbit) prove, almost anything can be willed into being with enough courage, humour and inspiration. As such, it’s a history but it’s an index of future possibilities too.

Philip Harrison

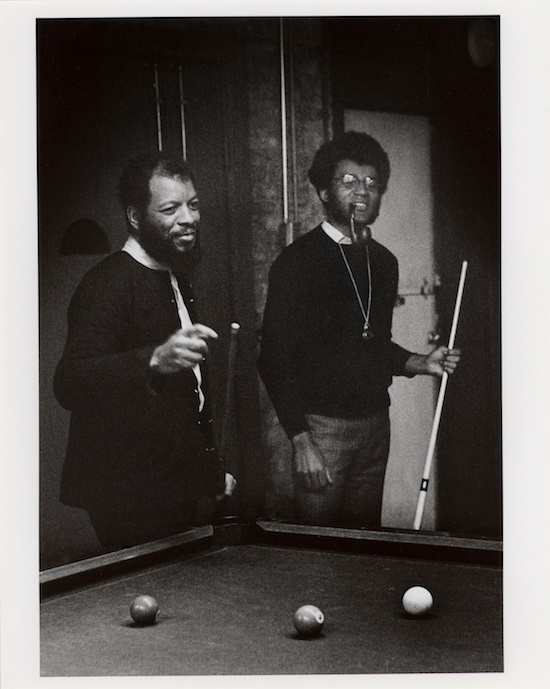

As Serious As Your Life: Black Music and the Free Jazz

Revolution, 1957-1977 – Val Wilmer (1977)

Ornette Coleman and Anthony Braxton play pool in New York, 1971: photo by Val Wilmer

First published in 1977, this thrilling and enlightening account of the new black music in 60s and 70s America offers vivid depictions of free jazz revolutionaries like Sun Ra, Albert Ayler and Ornette Coleman, and explores their genius against a backdrop of social, racial and political struggle.

Jazz writer, photographer and music historian Val Wilmer also examines the culture’s deep-rooted gender imbalance (ie Sun Ra’s exclusion of women in the studio, lest they cause a ‘distraction’), and gives welcome credit to the crucial roles performed by women, on and off stage: she celebrates the mothers, grandmothers, sisters, wives, managers and financial supporters who were, in the words of Clifford Thornton, “pillars of strength and encouragement”, alongside trailblazers like Alice Coltrane and Monnette Sudler.

As Serious As Your Life, which was reissued by Serpent’s Tail earlier this year, is a fascinating book that’s as radical, liberating and vital as the free jazz at the heart of its subtitle.

Nicola Meighan

The Sex Revolts: Gender, Rebellion And Rock ‘N’ Roll – Simon Reynolds and Joy Press (1995)

Some couples do crosswords or home remodeling projects, but imagine Simon Reynolds and Joy Press whiling away the connubial evenings of 1994 and 1995 with this unsparing dissection of ‘rock’s psychosexual underpinnings’. The Sex Revolts was hardly the first book on gender and rock, but like nothing before it proved how rich and accessible an analysis rooted in critical theory could be. In these proceedings, ‘more like an interrogation than a trial,’ the bad cops all have footnotes. Here is Gilles Deleuze, Gramsci, and The Clash’s soldier-boy posturing; Lacan, Lydia Lunch, and Julia Kristeva; the Freikorps, the Orb, the Beats, and body horror. For plenty of readers, this callow youth among them, following Reynolds and Press down ‘the path of critical awareness’ made the contradictions of rock’s rebellion permanently unignorable, and made rock itself never sound the same way again.

Andrew Holter

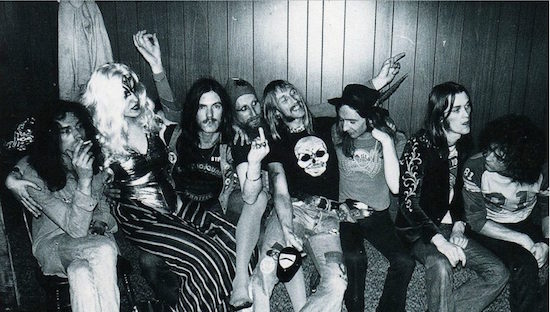

The Saga Of Hawkwind – Carol Clerk (2004, updated 2009)

The late Melody Maker journalist Carol Clerk was deeply embedded in the music scene of the 80s, holding her own with ease against any given rock star in the boozy culture that accompanied the inkies through their heyday. This is revealed in her expert biography of the apparently immortal space-rockers Hawkwind, written in a breezy but thorough style that floats through your brain as smoothly as a vintage MM article or indeed, any of the mind-addling substances so associated with Hawkwind’s music and philosophy. The book powers effortlessly along, from the band’s early days with Lemmy playing bass, singing their biggest hit ‘Silver Machine’ and being booted out for taking the wrong drugs, through to the ever-fluid group’s later and current status as senior statesmen of English psychedelia. When Clerk died in 2010, Hawkwind’s leader Dave Brock expressed his admiration for her book – the goal of any third-person biographer.

Joel McIver

Houston Rap Tapes – Lance Scott Walker (2014)

Breaking free of the artificial east coast vs. west coast narrative in hip-hop became a hell of a lot easier when Atlanta rose to prominence with the post-millennial trap revolution. Even still, rap progenitors in American cities down south like Memphis and New Orleans remain largely underserved by literature. Put together by native Texan Lance Scott Walker, Houston Rap Tapes lets the talent speak for themselves. An impressive oral history paired with stunning shots by Peter Beste, a photographer better known for documenting the black metal scene, Walker’s essential book rightfully presents H-Town as a hip-hop stronghold, with entertaining and informative interviews with everyone from Bun B and Paul Wall to DJ Gold and KB Da Kidnappa. The spectres of departed legends DJ Screw and Pimp C loom over the pages, yet more often than not Houston Rap Tapes showcases the breadth of a scene far bigger and deeper than some might suspect.

Gary Suarez

Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History Of Punk – Legs McNeil and Gillian McCain (1996)

Iggy

McNeil & McCain’s Please Kill Me is the definitive account of the Blank Generation. it chronicles the self-destruction and wild energy of Warhol’s Factory, Max’s Kansas City, CBGB’s and No Wave scenes and is told verbatim through connected musicians, artists, interlopers and writers. Frequently gossipy, and in many places hilarious and equally tragic, this meticulously researched tale of the birth of American punk is an essential read. Detroit’s MC5 and The Stooges provide the highlights with one of the finest warts-and-all accounts of Iggy Pop’s rise and fall, including interviews with the Ashetons, Danny Fields, Wayne Kramer, Alan Vega and John Sinclair. The central argument is that the British killed punk by taking an American tradition – which started with garage – and neutered it. It is written with such finesse that you may well read it in one go. Please Kill Me is truly exceptional and a must-have for any music library.

Adelle Stripe

The Importance Of Music To Girls – Lavinia Greenlaw (2007)

“I knew all the words to Nashville Skyline long before I knew what they meant: LAY LAY DEE LAY, LAYER PONYA BIG BRA SPED … UNTILLA BRAKE ODAYEE … LEMMY CEEYER MAIKIM SERMIYUL,” writes Greenlaw. “I was not interested in who Dylan was or even what he said but in how he said it. He had difficulty finding words and then couldn’t get them out straight. I imagined them swelling on his tongue and pushing each other out of shape. ‘Lay Lady Lay’ was, I thought, a song about delay (and I was right).”

When teenage boys are talking about labels and producers and blah blah facts and figures and cataloguing their ‘knowledge’, teenage girls are dancing and feeling and enjoying. Enjoying the bass and the swoon and the rhythm and the language. Yes, I’m generalising: deal with it. This extraordinary book from poet Lavinia Greenlaw is a kind of memoir in fragments, song by song, school discos and crushes and kisses and intense friendships; then the teenage years fade and the music stays.

Anna Wood

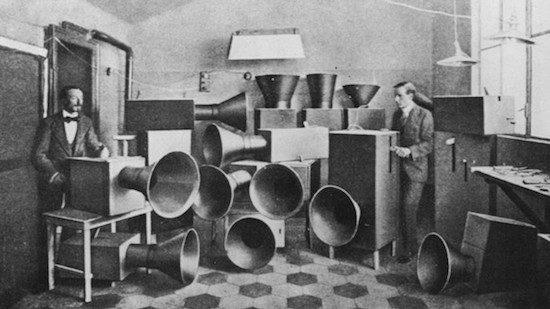

The Art Of Noises – Luigi Russolo (1914)

Russolo and his intonarumori

Italian Futurism’s influence in the avant-garde arts can at times be hard to fully comprehend. While artists like Umberto Boccioni and Carlo Cara made ground in the visual arts of 1910s Italy, Luigi Russolo had already produced a work that could be regarded as an indispensable blueprint for, industrial and noise music. The Art of Noises, is essentially Russolo’s manifesto for a kind of new music, the music of the future. Proclaiming ‘Ancient life was all silence’ and citing industrialisation as the beginning of Noise, Russolo’s work is seminal in the idea of comprising manmade timbres and textures into music. This, when paired with Teatro Constazi’s Musica Futurista, could be seen as the mother of electronic music. If not always directly, the work certainly influenced the likes of Throbbing Gristle, Einstürzende Neubauten and The Radiophonic Workshop, so when delving into such territory The Art of Noises is the perfect place to begin.

Aimee Armstrong

Seduced And Abandoned: Essays On Gay Men And Popular Music – Richard Smith (1996)

The late, great Richard Smith was a wonderful writer with rapier wit combined with a lightness of touch, even as he tackled the heaviest of subjects. In this collection of essays, Smith covers a broad range of music – from Mixmaster Morris to the Happy Mondays, via R.E.M., Stock Aitken Waterman, RuPaul, The Kinks, Suede, David Bowie, Nirvana, Morrissey, Freddie Mercury and Erasure (spoiler alert, he’s not a fan) – looking at the many and varied way in which gay men create, shape and interact with pop music.

Culture and identity politics, popular music as a platform from which to interrogate sexuality and gender, responses to the AIDS crisis and Smith’s own notes on camp and ‘ambisexuality’ are explored in a series of short but deep and loving essays that are serious but never sober. Playful, provocative, opinionated and profound, Seduced And Abandoned is a stunning collection of popular music writing (my copy has been overdue at the John Barnes library in Camden since May 7 1998, sorry), and highlights the huge vacuum left by former Gay Times and Melody Maker writer Smith when he died in 2017 aged just 49.

Adrian Lobb

Encyclopedia Metallica – Brian Harrigan and Malcolm Dome (1981)

Back in 1981, books about rock music were few and far between, with heavy metal in particular being poorly served. In fact, there hadn’t been a book dedicated to the history of the genre until Encyclopedia Metallica popped up in my local WHSmith. Less than 100 pages, and most of those taken up with black & white photographs of variable quality (though the pic of Judas Priest in full-on leather & whips gear is priceless), it nevertheless delivers an entertainingly didactic overview of metal’s creation story and beyond. But what makes this book really fascinating is its in-the-moment commentary on the still-emerging ‘New Wave Of British Heavy Metal’ (NWOBHM) – Iron Maiden are correctly identified as potential world-beaters, while Def Leppard are practically written off. Yet of their three “most significant” bands, only Girlschool enjoyed success at the time, although Diamond Head and Angelwitch have since achieved cult hero status.

Joe Banks

Meet Me In The Bathroom: Rebirth And Rock And Roll In New York City 2001-2011 – Lizzy Goodman (2017)

The joy of Lizzy Goodman’s hefty oral history of 00s New York City rock lies in the sweet, intimate anecdotes that humanise those impossibly nonchalant stars from an otherwise overexposed era. More than anything it serves as a love letter to that concept of New York City that pretty much all rock fans have had in their heads since first hearing the opening bars of ‘Sunday Morning’, and then all over again when they first heard ‘Is This It’ – and there’s something kind of charming about realising that all these artists felt that same, over-romanticised pull to the place. Be it the now-late Stewart Lupton of Jonathan Fire*Eater bemusedly recounting meeting Elliott Smith in a bar, Albert Hammond Jr.’s harrowing apology for “ruining” the Strokes’ dreams with his addictions, James Murphy taking ecstasy for the first time and giving the whole club sticks of Juicy Fruit chewing gum, or just generally remembering how badass Karen O is – this book is a thrilling and immersive time capsule.

Tara Joshi

Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History Of The Hip Hop Generation – Jeff Chang (2015)

Afrika Bambaataa

In 2017, for the first time ever in the US, hip hop officially outstripped rock music in the popularity stakes. Not that stats are needed to prove what’s long been obvious: hip hop is the defining music of our time. In this authoritative guide, Chang – journalist and co-founder of the Solesides label – skilfully corrals the genre’s sprawling narrative into a coherent, colourful overview that’s as strong on the socio-political whys and hows as the personalised whos and whens. Beginning with brief histories of the Bronx gangs and Jamaican dub, it then introduces DJ Kool Herc and Afrika Bambaataa, hip hop’s principal architects, before powering through the rise of B-boy culture, Public Enemy, gangsta rap and the rest, ending with protests against the deportation of former gangbanger turned community peace broker Alex Sanchez, in 2000. The book was published in 2005, so an update in kind is overdue. We’re all “the hip hop generation” now.

Sharon O’Connell

Copendium – Julian Cope (2012)

Of all the musicians who have excelled of late in the business of writing about music, Julian Cope is the daddy as this collection just goes to show. It’s essentially a bunch of album reviews and artist/scene primers but fresh takes abound and obscure acts are hailed as pioneering heroes. Find out why Miles Davis’ often maligned "sell out to funk" period shares much with krautrock, Japanese free-rock and proto-metal. Discover that the best Black Sabbath album is a live bootleg from the Sabotage period. Be introduced to Crow Tongue, Liquorball and Haare. Influenced by Lester Bangs but certainly written in his own unique voice, Cope’s use of language is a joy. His words leap off the page in a way that’s out of reach for much of the dreary music writing that’s around these days. How’s this for an opening sentence? "Place this disc upon thy stereo system and watch the so-called real world first recede then evaporate in mere moments, as the undead Ancients of the Underworld reawaken, then emerge triumphant to restore their bizarre death dance to our landscapes." You don’t get that in the po-faced thinkpieces of [name of publication redacted so as not to jeopardise any potential future commissions].

JR Moores

I’m Not With The Band: A Writer’s Life Lost In Music – Sylvia Patterson (2016)

In just a few paragraphs of dynamite prose it’s clear that they don’t make music writers like this anymore. I’m Not With The Band maps the ups and downs of Sylvia Patterson’s career, from the moment she arrives off the train from Scotland to work at Smash Hits, to declaring she is ‘too old for this’ after a particularly nasty internet exchange with wispy LA band Warpaint.

Come for the anecdotes about Jarvis Cocker, ‘a human lamppost in a brown wing-collared seventies shirt’, reading bedtime stories over hot chocolate in a single hotel bed. Stay for Liam Gallagher bragging about Patsy Kensit while the writer, sick after a dodgy curry, scoops her own puke out the sink in case her hero needs to use the bathroom.

Amid these top-drawer tales about the stars, Patterson charts her battles with alcoholism, the death of her mother and the irrevocable change in music writing as it becomes a joyless PR racket, chronicling a life in music the likes of which a writer may never have again.

Hazel Sheffield

Rip It Up And Start Again: The Story Of Postpunk 1978-84 – Simon Reynolds (2005)

Published at the tail end of the post-punk revival, Rip It Up And Start Again takes an encyclopaedic look at post-punk and every tangentially-related genre of the late 70s and early 80s. Simon Reynolds looks into not only the developments of bands and sub-genres, but labels, zines, and local scenes to give a complete picture of the patchwork of the industry in a pre-digital era.

The book is an increasingly valuable artefact; included in the over 100 interviews are legends such as Tony Wilson and Ari Up who have passed since its publication, as well as an interview with John Peel.

Rip It Up… makes encouraging reading just now. Many interviewed addressed how their work responded to despair about the rises of Thatcher and/or Reagan, taking their tactics not just from Bowie and Iggy but also Dada, Burroughs, and other outsider art. Today’s artists are bound to find inspiration from these stories, and they may not be musicians.

Amanda Farah

Do It For Your Mum – Roy Wilkinson (2011)

BSP

Anyone who’s been a long-time fan of British Sea Power will no doubt have enjoyed the regular missives from Old Sarge, aka Roy Wilkinson, the elder brother of band members Jan and Neil. Old Sarge’s emails – or newsboosts – were more than just mere PR, instead opening the lid on the band’s worldview and aesthetic inspirations, always as broad and deep as a Scottish loch. Do It For Your Mum takes a similarly expansive approach. It’s far more than a rock biography, instead a frequently moving and tender account of a family whose parents, older than the norm (their dad served in the Second World War), offered steadfast support to their sons rock endeavours. With the recent relaunch of Rough Trade’s book imprint it’s hoped that this beautifully written tome might once agains see the light of day.

Luke Turner

Sounds Like London: 100 Years Of Black British music In The Capital – Lloyd Bradley (2013)

As an immigrant and a south London resident, I realise I’ve taken for granted London’s ‘soundtrack’ – the steelpans outside the Iceland in Brixton, reggae pouring from my neighbour’s window, sound systems at squat parties – uncritically absorbing this as part of the fabric of life here. Sounds Like London provides the socio-historical context of this ‘soundtrack’, tracing the impact of Black musicians, not just on London, but nationally and internationally, from the Southern Syncopated Orchestra in the 1920s, through the calypso of the Windrush generation, to the success of today’s grime artists. Building a complex genealogy and providing absorbing insights into the innovation of genres and scenes, Bradley’s book weaves the material aspects of the music industry, both DIY and commercial, with interviews from key players, examinations of the political climate and a nuanced understanding of the continued negotiation of Black British identity through music.

Melissa Steiner

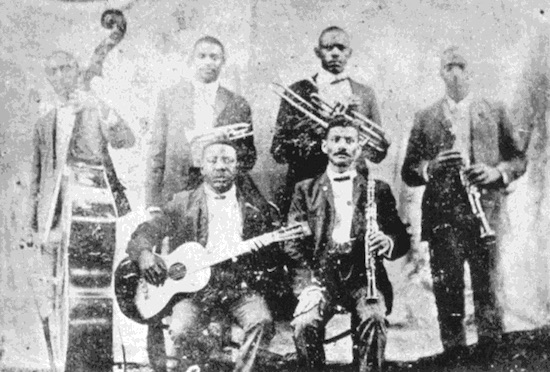

Hear Me Talkin’ To Ya: The Story Of Jazz By The Men Who Made It – ed. Nat Shapiro and Nat Hentoff (1955)

Buddy Bolden (standing, second left) with his band, including Jimmy Johnson (far left)

A packed-full treasure trove from 1955, this book is made up of dozens of conversations taped by wonderful editors Shapiro and Hentoff, plus various dips into print archives to uncover first person accounts from the early years of jazz. They’re edited so beautifully, like a script, so on any single page you might find Louis Armstrong, Jelly Roll Morton and Alphonse Picou discussing parties in Storyville; Danny Barker and Kid Ory remembering Buddy Bolden (“he’d put his horn out the window and blow, and everyone would come running”); Mary Lou Williams telling us about “the fabulous Ma Rainey” and Lester Young (“brother, what a horn”); Ethel Waters (oh, how I love Ethel Waters) recalling nights with Jimmy Johnson in Harlem: “He stirred you into joy and wild ecstasy”. Bessie Smith, Dizzy Gillespie, Duke Ellington, Billie Holiday, they’re all in here, chatting: a long jazz conversation, a panoramic jazz memory, rich, skilful, joyful.

Anna Wood

More Brilliant Than The Sun: Adventures In Sonic Fiction – Kodwo Eshun (1993)

When you open the first pages of Kodwo Eshun’s incredible More Brilliant than the Sun: Adventures In Sonic Fiction you are immediately dropped into a K-hole wonderland where humanistic limits and boundaries are no longer there, while the conceptual and linguistic ground is constantly shifting under your feet.

Eshun doesn’t write the standard book of music criticism that lays out dates, events, releases and the like. Calling himself a “concept engineer” instead of a writer, he creates a text that is an Afrofuturist polemic-as-manifesto, a screed of theory-as-science fiction, complete with dense passages full of techno-neologisms and non-linear jumps in narrative and temporality. For some, this style was off-putting, with some reviewers at the time wondering why he just couldn’t write the book in plain, accessible language. This completely misses the point – the language of the book, like the music contained within, needed to be read as if the text itself had come from an alien future, squeezing itself uncomfortably into the linguistic constructs of the present.

Today, as mainstream culture tendencies are still bogged down by, as Mark Fisher noted, “pastiche, recapitulation and a hyper-oedipalised neurotic individualism”, packaged as witlessly authentic, painfully sincere, everybloke indiedancepop, Eshun’s ideas and writing are more vital than ever. With afrofuturism presenting itself increasingly in the mainstream with Beyoncé and the success of the Black Panther movie, the cyborg queerness of FKA Twigs and Janielle Monae, to the underground guerrilla sorties of Moor Mother, and the NON music collective, we should stop trying to keep our feet on the ground and realise that space if the place to be.

Bob Cluness

When The Music’s Over: The Story of Political Pop – Robin Denselow (1989)

Neil Kinnock and some dear Red Wedgers

Attempting to chart the entire history of the symbiotic relationship between politics and pop music in a book of fewer than 300 pages might seem an absurd undertaking, yet in this somewhat forgotten tome Robin Denselow chooses his artists, movements and social issues with such informed acuity that he can trace a common thread of activism from Brecht and Weill right through to Billy Bragg’s Red Wedge of 1985 and beyond, via Woody Guthrie, The Fugs, Harry Belafonte, Gil Scott-Heron, The Clash and plenty of others. The year of publication, 1989, also makes this book intriguing, its tone and spirit affected by the fact the Berlin Wall was still intact, South Africa was still under apartheid, Thatcher was in power, and Chinese unrest would result in the Tiananmen Square Massacre of that year.

Denselow is reluctant to credit any music or musician with bringing about profound or long-lasting change, and indeed the book’s best moments come with his critical analysis of those occasions when the combination of politics and pop has been blindly celebrated. On Bob Geldof and his motivations for Live Aid he writes, "Charity on this level can be seen as favouring the Right, because responsibility for tackling social ills is taken away from the state, and placed in the hands of the individual, or voluntary organisations." Elsewhere, John Lennon’s ‘confused’ politics come in for mild reprimand, while Denselow explains in compelling detail exactly why Paul Simon was in the wrong to record parts of Graceland (an album Denselow adores) in South Africa, famously flouting the UN-endorsed cultural boycott of the country.

When The Music’s Over falls down slightly in its lack of engagement with pop’s impact on sexual politics, yet it is a fascinating cultural-historical artefact from a particularly disorienting point in history.

Barnaby Smith

An Individual Note Of Music, Sound And Electronics – Daphne Oram (1972)

Daphne Oram’s An Individual Note of Music, Sound and Electronics originally published in 1972 is a dense treatise on electronic sound and music that provides as much of an insight into these practices as it does into Oram’s notably eccentric views. Co-founder and at times most overlooked of The BBC Radiophonic Workshop, Oram touches on issues surrounding acoustics & cybernetics along with mathematics and esoteric thought, yet never strays too far away from the human; she encourages us to “see whether we can break open watertight compartments and glance anew”.

This urging to find new ways to observe comes to the forefront in her tilting of the different chapters in the book – her mind clearly processing information and making connections instantly, most evident in the excellently-titled ‘Complexity – 543/600 Hz – closeness – 200/600 Hz – harmonic relationship – shifting formants – art – inhibition/excitation – tightrope – insanity – drugs – expansion/contraction – squaring – excess overtones – spark – white noise – madness’.

Alex Weston-Noond

Everybody Loves Our Town: An Oral History Of Grunge – Mark Yarm (2011)

Everybody Loves Our Town does for grunge what Please Kill Me did for punk. This oral history isn’t restricted to bands from Seattle (the ‘town’ of the title) but pretty much every act that had an impact on or was affected by the late ’80s/early ’90s alt-rock explosion: L7, Stone Temple Pilots, Guns N’ Roses, Bikini Kill, Smashing Pumpkins… you name ’em. Nor are Yarm’s subjects limited to musicians as he also offers the perspectives of producers, journalists, label personnel, booking agents, record store owners, MTV news anchors, self-described "hangers-on", and the Sub Pop staff room’s kitchen sink.

Basically he’s spoken to every man, woman, his or her dog, and probably the dude who sorted out the dogs’ merch for them as well. Sometimes their memories contradict each other but the book gives you a real flavour of the craziness of that time. It’s an entertaining read but a progressively sad one as well. The really upsetting thing is the way the so-called grunge scene felt so fresh at first – sarcastic, grounded, feminist, unpretentious – and yet it still couldn’t stop itself from spiralling into the same old clichés as a million rock scenes before it. Fame. Drugs. Money. Yes men. Lackeys. Two-faced corporate suits. Egos. Bitter Rivalries. The dilemma would tear apart Seattle’s brightest star.

JR Moores

The Best Of Smash Hits – Various, compiled by Neil Tennant (1985)

The Best Of Smash Hits was released in April 1985 as a collection of interviews and features from 1978 to 1984 for a snipular £2.99, and compiled by Neil Tennant.

The magic of Smash Hits was that the voice of the magazine always felt like an excitable friend, and helped configure my mindset, language and general attitude to pop. For Smash Hits was never just ‘for the kids’ and this collection is as valid a time capsule of the post-punk/ new pop era 78-84 as anything Paul Morley drafted.

All the key acts are in there as you’d expect. It becomes like a Hall of Fame with each piece finding the subject at a significant point in their careers, be it the first features of Gary Numan, Specials, UB40, Duran Duran, Culture Club and Spandau Ballet. That dizzy, unbottled moment of things about to explode with Frankie Goes To Hollywood, ABC and Yazoo, the only chat Michael Jackson will do with a UK magazine, an early peculiar and exciting encounter with Morrissey plus an At Home with Joanne and Susan from the Human League. It’s all here.

An essential time capsule of a fantastic period. If you can find one, grab it.

Ian Wade

Future Days: Krautrock And The Building Of Modern Germany – David Stubbs (2014)

Krautrock is a contested, borderline offensive term that has been rendered almost pointless by overuse, according to David Stubbs in Future Days.

Early in the book, Stubbs recalls his classmates ridiculing him when he played them a Faust record. Across 500 pages, Stubbs gets to make his ultimate defence of Krautrock through interviews with some its leading lights, even as he lambasts the term itself for being reductive. Future Days finds the common thread between a series of West German bands of the late 1960s and 1970s, from household names like Kraftwerk, Can and Neu! to more obscure acts like Xhol Caravan and the Cosmic Jokers, arguing that they emerged precisely when they did because of a “process of renewal of identity” when young Germans refused to be defined by their parents’ wartime experiences.

Alongside a painstaking exploration of the enduring influence of Krautrock, Stubbs presents a convincing case for this being a fundamentally forward-looking music. ,Kosmiche, indeed.

Ian Wilkinson

Everybody Was Kung Fu Dancing: Chronicles Of The Lionized And The Notorious – Chet Flippo (1991)

The late Chet Flippo hid in plain sight, demonstrating depth, range and a clear authorial voice that understated rather than shouted. Everybody Was Kung-Fu Dancing, drawing on his wide number of articles from the 1970s and 1980s, has profiles of authors, actors, his fellow “Texans in New York” and more, but his musical efforts are the deserving core. He effortlessly treated rock and roll and country hellions and legends as part of the same continuum, creating a series of near-definitive profiles ranging from Chet Atkins to Jimmy Buffett to Jim Carroll. But his ‘Rock’n’Roll Tragedy: Why Eleven Died in Cincinnati’ may be the highlight, a carefully reported and calmly polemical portrayal of the disastrous 1979 The Who concert there that, in its detailing of a fatal crush of people, indifferent authority figures, victim blaming and too much more, seems all too eerily like a foreshadowing of Hillsborough a decade earlier and a continent away.

Ned Raggett

Blues People: Negro Music In White America – Amiri Baraka (as LeRoi Jones) (1963)

Bessie Smith

Published just as the American civil rights movement was kicking into high gear — and a couple of years before Malcolm X’s assassination inspired LeRoi Jones to reject his western name and become Amiri Baraka — Blues People is more a polemic on the history of African-American music than it is a historical recounting, and this is perhaps its essential strength. Baraka peels off the polite veneer of musical integration, revealing jazz and blues as the natural result of African ingenuity in the face of European monstrosity, a great artform whose existence is nonetheless tragic. Baraka’s prose is all slash-and-burn, slanted as it is succinct, and unlike supposedly related works (Alan Lomax, Samuel Charters, etc), it offers no romance and pulls no punches, refusing to let the reader forget for a second that ‘America’s music’ is the direct result of the brutality inflicted on its performers and their ancestors.

Dustin Krcatovich

Perfecting Sound Forever: The Story Of Recorded Music – Greg Milner (2009)

The whiskery old joke about Wagner – that his music “is better than it sounds” – assumes a new resonance in the light of this excellent history of recorded music, which examines how the processes that produce vinyl, CDs and MP3s have shaped our listening. Milner tracks the story from a demonstration of Edison’s Diamond Disc Phonograph in 1915 to the widespread use of Pro Tools, talking to musicians, producers, record company execs and tech developers along the way. Which might sound dry as dust, but although his work is extensively researched and isn’t shy of technical analysis, it’s also that of a music enthusiast, fascinated by the alchemy that enables us to fix sound in time. Milner maintains a strong narrative pace that injects vitality, shares some personal enthusiasms and writes engagingly on everything from dub and pink noise to the “loudness war”. On which note, should any reader seek vindication of their raging intolerance to the Red Hot Chili Peppers, they’ll find it here.

Sharon O’Connell

Never Mind The Bollocks: Women Rewrite Rock – Amy Raphael (1995)

Following a foreword by Debbie Harry and a chapter outlining a brief history of women in rock, Raphael introduces a series of in-depth interviews with, or monologues by, the leading women on the scene, circa 1995. After years of being sidelined and misrepresented, there was a short-lived optimism in the air. “What links the women in Never Mind The Bollocks is their comparative success in dealing with the male-dominated infrastructure,” wrote Raphael.

Interviewees including Bjork (probably the book’s high point), Kim Gordon, Huggy Bear, Courtney Love, Echobelly’s Sonya Aurora Madan and Debbie Smith, and Kristin Hersh offer a snapshot of the times, a sense of real solidarity and a shared shitty history of industry misogyny. As an antidote to the boys’ club that so much of the music industry, from artists to label bosses to journalists, was and is, it is essential reading. And if it sounds like a book that requires an updated edition, detailing a new generation of artists, well, there’s good news. In 2019, Raphael will release a follow-up for Virago, featuring interviews with 20 more women from across genres.

Adrian Lobb

The Last Party: Britpop, Blair and the Demise of English Rock – John Harris (2004)

In a time of rising nationalism, a document of an attempt to brand a genre through patriotic cool makes for morbidly fascinating reading. John Harris wrote The Last Party during Britpop’s hangover, empathizing with the demand for distinctly British pop music (blame Nirvana) while leery of Union Jack waving.

The Last Party conveys the rollercoaster of the period: Genuine affection for artists at their peaks; nose-wrinkling at the rise of lad culture; disappointment at half the artists being pulled from their peaks by cocaine and/or heroin. Justine Frischmann contributes considerable insight into the extraordinary toll of a few short years on three key bands.

Harris’ wariness of Tony Blair and the politician’s readiness to co-opt a cultural moment was proven sound when the UK invaded Iraq two months before the book’s publication. Noel Gallagher posing with Blair marks a simpler time than the hellscape in which Alex James was snapped with David Cameron. Harris might have exaggerated how bad things were, but he was dead on about how bad things would get.

Amanda Farah