Let’s start with some history. Between 1980 and 1983, the then Acme Housing Association — a company that had been set up in 1972 to find cheap live-work spaces for artists in the East End — took over management of a large number of Victorian houses on and around Claremont Road in Leyton that had been compulsorily purchased by the Department of Transport, pending the construction of the M11 Link Road. These houses (and others around the East End of London that were owned by the Greater London Council, the former Inner London Education Authority and others) were rented out to artists on short-life tenancies.

By the early 1990s Claremont Road was on my radar. I’d long known the work of pioneering UK video artist and filmmaker — and Claremont Road resident—Ian Bourn, and now knew him, through his friend and one-time collaborator the late Helen Chadwick. Helen was a friend and neighbour in Beck Road—another community of artists living in ‘Acme houses’, as they were known—where I lived at the time. I followed developments in Leyton as those short-life tenancies came to an end, as people started being evicted, and as the protests grew.

More than that, this was a scene that I also quickly turned around in my own fiction, writing a deliberately loose and libidinised version of the M11 protests in what became my debut novel, the ‘avant-pulp’ Road Rage! which was published in 1997. Paul Hawkins has taken rather longer in reporting from Claremont Road, but in doing so he has perhaps been truer to the troubled textures of the time, and both more generous and more critical than I had cared to be with my own more immediate fictional responses.

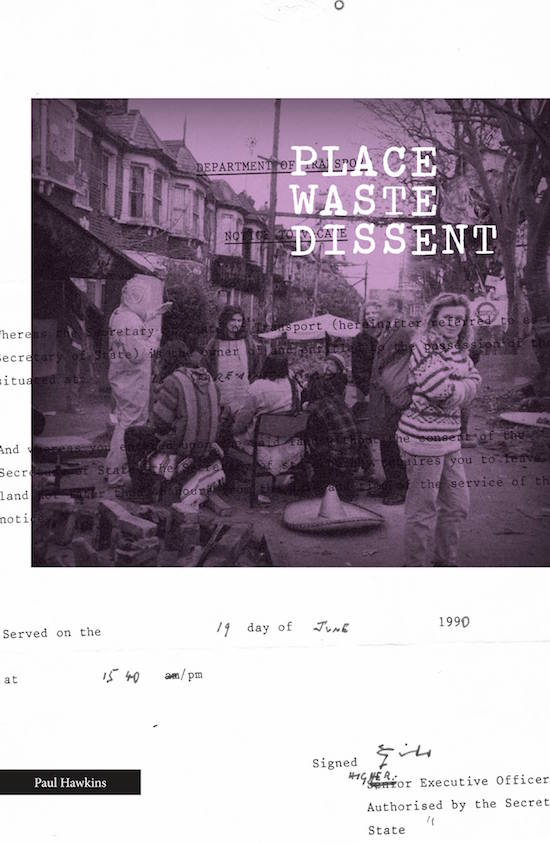

The lo-fi, analogue, cut and paste of word and image that Paul Hawkins presents in PLACE WASTE DISSENT is not only richly redolent of that early ’90s squat and crusty culture, it is haunted by characters and casualties of the era. Portraits that are sustained and affecting. Most notably we meet long-time resident Dolly, a ‘tat man’ named Old Mick, and a young girl nicknamed Flea, whose death a few years later reverberates throughout the book. A few old friends make cameo appearances, too. First Ian Bourn and co with HOUSEWATCH, a cinematic public art spectacular that is projected onto the windows of number 8 Claremont Road, from the inside: ‘we blink / stars around the sky / as window cine-film / loops the world … breath steaming to frost.’ Then (to declare an interest) my 1999 novel, the satirical policier and ‘stream of filth’ CHARLIEUNCLENORFOLKTANGO gets a name-check on p.122.

Some of these stories had been hinted at, the surface-scratched, in Hawkins’ previous more traditional pamphlet Claremont Road and in the more concrete approach of 2014’s Contumacy (both Erbacce Press), but the black-framed and collaged collisions of PLACE WASTE DISSENT bring further dimensions and velocities to these rich subject matters. Hawkins tells me that he’s always been interested in different approaches to language, dotting words around the page, using blank space, the cut-up. Recently he’s been reading contemporary poets such as Holly Pester, Steven J Fowler, Sean Bonney, Caroline Bergvall, Steve Willey, Frances Kruk and Sam Riviere: ‘People who are experimenting and collaborating.’ As one reads PLACE WASTE DISSENT — and it is a naggingly rewarding read — possible influences and references seem to also include Tom Phillips’ A Humument, the posi-punk monochrome of Crass album sleeves, and more recently Laura Oldfield Ford’s Savage Messiah. So how had he come to be living in Claremont Road in the first place?

Paul Hawkins: I’d been living this slightly itinerant life in and around Milton Keynes, playing in various bands—running and hiring out a PA that had used to belong to The Pink Fairies — and doing various different jobs, in and out of relationships. When I was about 25 I found myself living in the village of Aspley Guise not having quite got anywhere with the music, so I applied to the Polytechnic of East London to do a degree in Cultural Studies, and I got in. I was studying at the Poly in Stratford, on the main drag—an old tobacco factory I think — but I was broke, struggling to pay the rent and finding it increasingly difficult to make ends meet. That’s when I heard about Claremont Road, and I decided, Right, we need somewhere to live, I’m going to find a house. As it says in the book, I remember walking down this ghost street of boarded up houses. This whole mixture of smashed up houses with no roofs, no toilets. Someone had painted ‘God help us’ on one of the walls. I had a look around, I hadn’t squatted before, and I thought, well I’ll get round the back and have a look. I went in to one—can’t remember which—it was pretty messy, fairly trashed. I found evidence that someone had been sleeping there, a pint of milk that had turned to cheese, so I left them to it. I went into number 18 instead, by the back door. There was a smashed up piano in the back, the windows were boarded up, floorboards missing, but the stairs were okay. I decided that would do. Changed the lock, got a mate over to bring some stuff and that was it. That was when I bumped into Flea and Old Mick. Then we went over the road to The Northcote pub and started to get to know more of the locals. There was a mixture of people who’d been born there, and the artists who’d been living in the Acme houses — the artist filmmakers Ian Bourn, John Smith and others. There was Dolly, Gloria, Cathy, Russel, Code, Dodgy Dave, Popeye, Taxi Driver (I never found out his name, just called him Taxi Driver because I could see how he earned a living; it was parked outside), a bunch of Scottish labourers, students, families. Then as time went by a whole load of other people started turning up, more or less like I had, saying, ‘Are there any empties?’

The Acme houses would have been rented as ‘short-life’ tenancies that could have lasted anything from a month or two to a few years. Readers today may not be familiar with the short-life housing concept but it offered temporary homes that (effectively) traded longer-term security for low cost. There were various co-ops and housing associations working in that way at the time, not just Acme, but the Westminster Short Life Housing Co-op, too, for example. Was it common knowledge that the community was living on borrowed time in this way?

PH: Yes, rumours had been going round for ages, but no one knew quite when the end would come. I went to meetings and met people like Richard Leyton, chair of the No M11 Link Road campaign, Colin Bex, the then Labour MP Harry Cohen, and others, to try and find out what was going on. I was interested in what was happening and how the protest was being conducted, through legal objections, enquiries, public meetings. Polite protest working its way through a framework of legal process, that became more ingenious, radical, provocative and direct as time passed. People were complaining about the number of decent houses that were being knocked down at a time when homelessness was an issue, and about the communities that were being uprooted. There was talk of the rat runs, the traffic and the pollution that would be created by the new road. And all this time evictions were going ahead. There seemed to be a blurring of the roles of the demolition people and the police. Houses would be left in unsafe conditions. There were gas leaks, flooded basements, unsafe walls and roofs. Then the involvement of the police in the eviction process. There were wrongful arrests and surveillance, aggression, harassment. As soon as people were evicted you would hear the demolition guys going in with sledge hammers. We were trying to stop them smashing the houses up. For us there was this dual drive of wanting these perfectly good houses to continue to be lived in, and wanting to delay things, to make the job of demolition more expensive, to stop the road being built. There was a general feeling of distrust of the Thatcher-Major axis, and of global capitalism.

Among the extensive and very evocative contemporary documents and ephemera that you’ve used in PLACE WASTE DISSENT, the flyers and the mocked up ‘Obs Sheets’ — police observation notes — is a very interesting photocopied who’s who, an updated list of occupants and state of repair of all the Claremont Road houses: ‘15: Mick, squatted … 32: Dolly’, etc. Some of the houses had evidently gone through this cycle of destruction several times. Number 16, for example, reads: ‘TRASHED SQUATTED TRASHED SQUATTED’. It’s only a matter of time, you get the feeling, before that would have been crossed out again. A lot of these papers are from your own collection. How on earth did you keep hold of all this stuff?

PH: Whenever anybody got served legal papers, eviction papers, they would be photocopied and circulated. There was a solicitor involved who had people looking at these materials, and everyone passed the papers around. I started keeping a folder, a big ring-binder with all these plastic sleeves full of magazine articles, notes, posters from benefit gigs, letters, everything. It seems bizarre because at that time in my life things were getting a bit messy around the edges, but somehow whatever else happened I managed to keep it all safe.

Years later, when I was putting the book together, I was also able to refer to a huge archive of No M11 Campaign materials held at the Museum of London which included local, national and international newspaper coverage. A curator there called Beverley Cook was very helpful. I made an appointment to view this, taking copious notes. There were all these ’zines and magazines, a local broadsheet called The East Ender. Around the late ’80s and early ’90s there were a lot of crusty, traveller, eco-campaigners. There were squat bands, anarchist bands. This was the tail-end of the rave scene and the beginning of things like Reclaim the Streets.

This really was a kind of front line at the time.

PH: Yes, and with other protest groups, other proposed motorways, at Newbury, the Dongas at Twyford Down, the M77 and Pollok Free State and the Anti-Criminal Justice Bill protests.These and other groups were not cohesive but there were means of contact, which grew in strength. The increasing media awareness both helped and hindered. I wondered how protesters saw themselves and their politics. To what extent did antagonism to capitalism inform how they were coming together? What role did class play? A debate that’s often raged in my mind. The Verso book DIY Culture Party and Protest in Nineties Britain, edited by George McKay asks similar questions about DIY dissent that you don’t find easily in the mainstream media and historical accounts.

There’s a nice quote from the writer Joe Ambrose on the back cover, where he says you were once ‘a foot soldier banging on a revolutionary drum’, but that now you’re ‘a Homer immortalising his war.’ Why does Claremont Road still resonate?

PH: Personally, it was at a time when I was learning a lot more about politics, and becoming far more aware. My dad was a printer, a Trades Union member made redundant by Murdoch. I have a background of people getting together to fight for rights, and a penchant for the underdog. My studies at the time looked at Englishness through Marxist analysis; a critique of what it is to be English. I was coming to realise and learn that anarchism was not in fact a state of constant riot. I’d been involved with student campaigns, poll tax demonstrations in Trafalgar Square and Hackney, as well as the No M11 protest. It seemed the next step was to do something rather than learn about it or read about it. I wanted to live my life differently. In some ways Claremont Road was this idyllic space, a zone where I could develop that at a theoretical level, through study and discussion. I had space to make mistakes I guess, to learn from others. I think I realised that fighting it on a legal level was ultimately flawed because in the wider context it seemed like an illusion that you could have your say. Plus the people I met: all the anti-roads campaigners, and JB, Old Mick, Henry, and many others. Dolly! She was an amazing woman, born in Claremont Road, who had survived the two world wars, and continued to survive under the ongoing guerrilla conditions in the early ’90s. I wanted to use her voice in the book, to write parts of PLACE WASTE DISSENT from a female perspective, but it was a real challenge. Sarer (Hawkins’ partner, the poet Sarer Scotthorne) would read a draft and say, ‘A woman wouldn’t say that!’

These portraits of Dolly and Old Mick are very generous and affecting, we get to know them in the book, and we even go with you to their funerals. But some of the events at Claremont Road really were a matter of life and death for all concerned. It reminds me that, looking back, many of us could probably see one or two narrow escapes in our own pasts, pivotal moments that may not have seemed very important at the time, the magnitude of which might only become apparent much later. I’m thinking particularly here of the story of Flea, a teenage girl that you’d bumped into the day you moved in. She would occasionally seek refuge with you and your partner from her abusive home life, which at one point threatens your safety, too: ‘Any minute now they could be here smashing the windows, breaking down the door—we’re not safe … We pack really fast … We grab what we can and we drive.’

The emotional core of the book seems to be where you describe bumping into the grown up Flea years later, a shadow of her self, selling the Big Issue in Brighton. This seems in turn to shadow a struggle for change in your own life. In her introduction, Alice Nutter says that these stories are a reminder that Claremont Road was a very dangerous place.

PH: Yes, there were a lot of fucked up people there. What went on, how the campaign developed, how life developed, these are experiences, relationships and memories that will stay with me for the rest of my life. When you didn’t know what was going to happen from day to day. That struggle continued for me, through periods of homelessness and chaos. It was only once I got sober that I felt able to write clearly about those times. The recollection of this period also posed questions not only over the role of memory, but what it actually is; how it works within the twenty-first century of paradox, overload and despair versus rich opportunity and endless possibility.

Finally, what can we learn from Claremont Road now?

PH: Things that began at Claremont Road have continued. The road-building programme at the time was cancelled in the UK. But the political system hasn’t changed that much. On the surface it might appear to have done so, but things have got tighter: the control over the way we live our lives, the choices that we have, and the ramifications of what we do. The UK political system and the political parties are corrupt, self-serving in the pursuit of financial gain, the idea of democracy is a sham, the dominance of global capitalism continues. Make no mistake, the damage continues to be done. The continual threat of war. The ticking time-bomb of climate change. The rise of surveillance culture. I think we can gain heart from the fact that people were joining together to create a common space, and, however precariously, protest against dominant ideology, dominant power, and thwart the politicians and capitalists, and this continues in small pockets of resistance. Just as importantly we can also learn from its incoherence and its failings. The way it excluded certain people. Its lack of political cohesiveness. With hindsight you can see that, in the main, people of colour were excluded, women too. There have been critiques of the wider protest movements, some of which McKay touches upon and you can find plenty of discussion online. Personally, I think as long as you try to fix the broken system of capitalism, without scrapping it altogether, there will be no lasting change or improvement.

It is perhaps not surprising that these ideas, conflicts and energies play out and find visual, textual and poetic equivalences—and resistances—not just across the pages of PLACE WASTE DISSENT itself, but also in how Paul Hawkins describes the acts of writing and assembling it. He tells me that the book also came out of ‘a kind of slow-burning fuse of dissatisfaction’ about the way mainstream poetry is written and the poetic forms that are dominant both in wider culture and in academic discourse.

‘I was keen,’ he says, ‘to play with what is and isn’t poetry, because the idea of the poet having some God-given gift to portray the truth about anything seems like it has run its course in the 21st century. There are more exciting and interesting ways of representing the world. Kicking against those dominant forms. In a world full of uncertainty come endless possibilities.

‘That’s what I’ve tried to do,’ Hawkins tells me. ‘Although I wouldn’t say I’ve cracked it.’

Paul Hawkins’ PLACE WASTE DISSENT is out now, published by Influx Press