Sitting up late one night not so long ago with a bunch of musicians, I found myself immersed in the sounds of Prince’s Parade – a record that, at the time of its release, became something of an obsession of mine. But, in recent years, it’s been neglected on my shelves, pulled out only occasionally, and almost always for its closing track, the exquisite ‘Sometimes It Snows In April’. That night we played the record without pause, marvelling at the lack of bass on ‘Kiss’, and the way its percussion seems to distort ever so slightly; at the brilliant absurdity of the Caribbean steel drum on ‘New Position’; and at the swooning romance of ‘Under The Cherry Moon’, which flows like a river despite its deliberately plodding drum beat. We thrilled to ‘Mountains’, chuckled admiringly at the French pretensions of ‘Do U Lie’ and gasped at the sublimely inventive brass and wind arrangements on ‘I Wonder U’. We all agreed: Prince, at his finest – and1986’s Parade is unquestionably one of Prince’s finest albums – is triumphant.

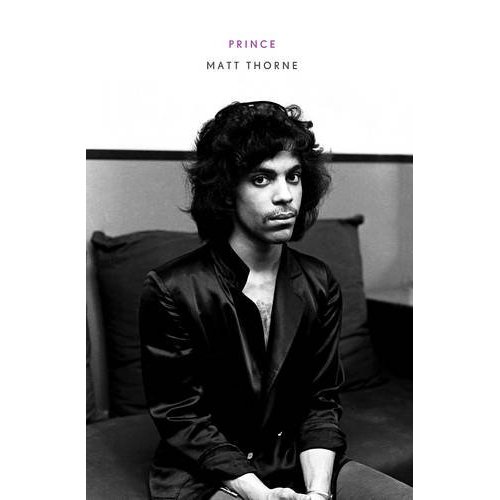

The arrival of Matt Thorne’s mighty tome, Prince, was therefore a welcome one. Despite my youthful passion for Prince’s work – which lasted five years from the first moment I heard 1984’s ‘When Doves Cry’ (from Purple Rain) to 1989’s Batman, after which my interest began to wane as his output became increasingly uneven and my love of indie rock correspondingly gained strength – I knew little about the man. Thorne’s “definitive portrait of the artist and his incomparable musical catalogue” seemed like a good place to start. Though my ignorance of the topic might initially seem to make me an inappropriate critic, it is not a unique condition. According to PrinceVault – the website named after the legendary depository for all of the man’s unreleased material – there have been 48 publications devoted to Prince (though this seems to include giveaways with magazines and the like), and yet he remains reclusive, unpredictable and mysterious. These 476 pages – plus a further fifty sides of notes – would surely be able to shine a light on his personality and music.

They do, but it’s a light that dazzles and blinds as much as it reveals. Matt Thorne is clearly as infatuated with Prince as anyone on this earth, and has undeniably invested a great deal of effort and time into this encyclopaedic volume – seven years of research, apparently. But working one’s way through this book is sometimes a grind, and not in the sexual sense that Prince himself might use the word. There’s no doubt that it’s packed with the minutiae of Prince’s recording career: the roots of huge numbers of songs are explored, set lists have been diligently digested to provide an intricate knowledge of which tracks the artist himself has most favoured, and where possible collaborators have been interviewed to better understand the man’s working methods. Somehow, though, little sense of Prince’s personality emerges, beyond a sex obsessed, progressively more controlling, musically gifted but often misguided individual who was a late convert to the Jehovah’s Witnesses.

The book starts promisingly with a prologue describing a party at the Purple One’s house in 2006 to promote the release of 3121, and hints that what’s to follow will be a personal voyage into the man’s music. Descriptions of “sinister Walt Disney-meets-David-Lynch architecture” and depictions of neighbours trying to gain access to the event are teasing and initially gripping: few people, asides from inner circle celebrities, are offered the privilege to get this close. But such intimacy is short-lived: before long we’ve set off on a journey that, while unafraid to criticise, remains nervous of prodding too deep below the surface, instead operating as a handbook, a comprehensive guide to huge amounts of material that, to the average music fan, remain frustratingly hard to track down.

Of course, there’s a certain fascination in discovering how Prince cannibalises his own work, lifting lyrics and musical phrases, even sometimes arrangements provided by Dr Clare Fisher – a man who he’s always, somewhat ungratefully, refused to meet, lest he jinx their work together – to create new music, and Thorne tracks these progressions carefully. He also plots a shrewd course through the many musicians with whom Prince has worked, as well as the side projects, protégés and business associates. But for those looking to learn more about the man’s life, it’s short of revelations, something Thorne concedes early on when he admits that, “it doesn’t help that Prince’s mythological approach to his past is shared by some of his family members”. Furthermore, for those looking for a deconstruction of that very mythology, it’s also a little superficial, dependent upon conjecture and insights from those who have worked with him but whom, for the most part, seem wary of giving away too many secrets. (Prince, inevitably, played no role in the book at all.)

Thorne’s academic and highly specialised approach might perhaps be less troubling if he didn’t draw attention to certain themes without offering significant investigation of them. The most disconcerting of all is Prince’s preoccupation with sex. Early on, Thorne refers to two unreleased tracks from the Controversy sessions that “both feature Prince threatening rape.” The sentence is surely enough to stop most readers in their tracks, and Thorne briefly recognises this. “If we are troubled by the songs,” he continues, “then does the fact that having recorded them Prince has (so far) exercised self-censorship and withheld them from a wide audience excuse their content?” But the question remains unanswered, as it does repeatedly the further one reads, beyond a subtle exercise in whitewash: “it’s easy to argue convincingly that he (Prince) needed to visit these artistic extremes”.

Later on, Thorne discusses another unreleased track, ‘Big Tall Wall’, about his onetime lover Susannah Melvoin, the sister of Wendy (of Wendy and Lisa): “Lyrically it’s unbelievably reactionary, a throwback to the lock-her-up-in-a-trunk misogynist crap of Cliff Richard’s ‘Living Doll’”, he writes, but though he appears to feel strongly about this, he’s soon acting as an apologist, excusing it as “a definite exercise in black humour.” Unable to hear it, or even read the words – lyrics are never quoted in depth, presumably something inflicted upon Thorne by Prince’s publishers – we’re left trusting the author, and he’s not given us great reason to do so, especially when he later refers to ‘Schoolyard’, a track dropped from Diamonds And Pearls, which Thorne coolly describes as “a sexually explicit autobiographical track which moves from a graphic description of the experience of entering 14-year-old Carrie’s vagina (compared to a glove filled with baby lotion) to a strange sermonising about how the listener might wish to protect their own children from similar experiences.” There are few attempts to reconcile these themes and next to no judgement about the sexualisation of a young girl, even if, in the notes, Thorne refers to a Rolling Stone interview in which Prince confesses it’s about “the first time I ever got any”, as though this makes it more warrantable.

Thorne is largely forgiving of Prince’s dirty mind – something that is naturally a huge factor in his work, and which is indeed sometimes comically played – it’s arguably more indicative of the fact he’s not as enquiring a writer as the subject deserves from a book this lengthy. The contradictions and sexual, political implications of Prince’s boasting, androgyny and his frequent attempts to write for women – often his lovers – remain disappointingly unscrutinised, just as his later spiritual awakening seems somehow glossed over.

Thorne also has a predisposition to superlatives, and there are only so many times that one can face down such declarations as “only here can you get a sense of the true power of a Prince And The Revolution show from this era”. One particularly effusive passage grates more than most, as Thorne gets carried away so far he seems to be deifying his subject: “Prince’s show at the Het Paard van Troje in The Hague was the third of nine after-shows he would play on the Lovesexy tour,” he writes, “and has become the most legendary after-show he ever performed. That Prince had the mental and physical stamina to create such an overwhelming experience in the middle of the night for the favoured few after what must have been an extraordinarily draining show in front of 30,000 people is a feat beyond any other (pop) musician.” Yeah. Right. Beyond any other (pop) musician. Of course.

It is perhaps unfair to criticise a book for not being something rather than acknowledge what it actually is. Prince is a thorough examination of almost every single song Prince has ever composed, as well as a handful that he didn’t but has still performed, given extra context by those who were around at the time of the writing or recording sessions. It draws upon a lifetime’s worth of listening to albums, live recordings, fanclub only downloads and more with the ear of an enthusiast. It will surely delight those for whom the knowledge that Graffiti Bridge started out as a thirty page script, one that Prince’s manager at the time suggested might make a better Broadway musical, is exciting. Furthermore, if you want to know what Thorne made of Prince’s 21 date residency at London’s O2 Arena – he attended nineteen shows and thirteen of the fourteen aftershows – then there’s an entire chapter for you.

But if these seem to be of little interest – and one can only presume that they’re not going to be of much interest except to the kinds of people who, in less than two months, would want to attend nineteen shows and thirteen after-shows in which Prince isn’t even guaranteed to perform – then Prince is perhaps not the book for you. Sometimes too much information is a bad thing, after all. What keeps us intrigued, despite Prince’s frequent stumbles, is his mystery. As the man himself might say: “Shut up, already. Damn!”

Prince is released on the 4th of October by Faber & Faber