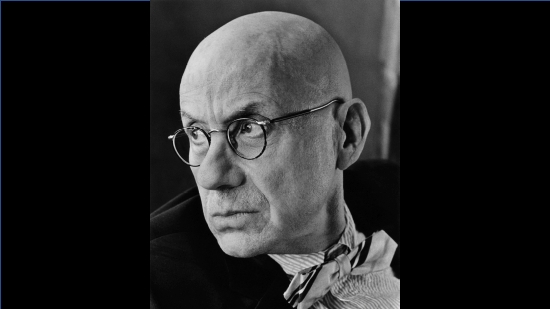

Photo (c) Marion Ettlinger

At 71, and halfway through his biggest and baddest set of stories yet, James Ellroy’s powers aren’t just undimmed, they’re growing. The shaved head and wire-framed glasses may be as much a trademark as the clipped, all-fat-ripped-off prose style, and the persona projected in public appearances and other kinds of performance – interviews most definitely among those – may remain that of the supremely self-confident "demon dog" of American letters: but, just like the characters in his massive books, there’s ever more to Ellroy than a collection of familiar tropes.

The Quietus meets him in a central London restaurant, all but deserted at 9am, with a waiter ill at ease when informing the gravel-throated writer that his chosen poison – prawn cocktail – doesn’t form part of the breakfast menu. Ellroy opts to have nothing at all, save a glass of hot water with a slice of lemon. It feels apt: the economy of the writing shadowed by the combination of convention-defying appetite thwarted, only to be replaced by ascetic denial.

Or maybe that’s just this reader, extrapolating far more from an inconsequential vignette than is actually there – an occupational hazard when reading Ellroy’s vast, complicated and evocative novels. His method is almost as maniacal as one or two of his more Machiavellian characters: the books take several years to construct, as a small team of researchers go out and hunt down details to keep the timelines accurate, then Ellroy constructs a separate other book – a framework against which he can align those tightly constructed sentences.

Often thought of as a crime writer, he’s actually (and additionally) a master of historical fiction, his hunting grounds being mid-20th century USA, often – though by no means always – his native Los Angeles. His extensive casts of characters – a 92-person, six-page dramatis pesonnae appears at the end of his latest – liberally sprinkle mischievous, sometimes outright malicious, caricatures of famous real-life people into the mix of invented individuals.

His lauded LA Quartet series of novels began in 1987 with The Black Dahlia, the first book in which Ellroy explicitly set out to confront the true-crime story that dominated his life from the age of 10: the still unsolved murder of his mother. Book three in the Quartet – LA Confidential – made his name twice over. Initially rejected by his publisher for being too long, Ellroy knew that none of its labyrinthine sub-plots could be cut without destroying the integrity of the whole: so he went through the manuscript line by line, excising phrases, clauses, individual words. The resulting style became his literary calling card, all excess confined henceforth to the actions depicted rather than the words used to describe them. The book became a hit, and the film adaptation made its author a star.

This Storm, just published, is part two of an in-progress Second LA Quartet, situated earlier in the century and featuring many of the same characters Ellroy wrote about in the 1980s and 1990s. Readers who first came across the corrupt cop Dudley Smith in the 1951-set Clandestine (written in 1980 and published in 1982), and followed the character backwards in time to 1942 in book two of the first Quartet, The Big Nowhere, then through the ’50s in LA Confidential and beyond in White Jazz, know how his story ends: but in This Storm and its predecessor, 2014’s Perfidia, we’re essentially presented with what, in superhero parlance, would be Smith’s "origin myth".

Long-term readers are also reunited with familiar faces in their earlier years, including LAPD sergeant Turner "Buzz" Meeks, officer Lee Blanchard, and his enigmatic paramour, Kay Lake, whose diary entries appear in both books and signal yet another change of style for Ellroy. There are walk-on parts, where appropriate, for folks we met in the ’60s-set Underworld USA Trilogy – American Tabloid, The Cold Six Thousand and Blood’s A Rover – and characters new to the Second LA Quartet, such as the brilliant Japanese forensic scientist Hideo Ashida, and Elmer Jackson, a real-life LA cop.

The setting is Los Angeles early in World War Two, a city flying off its hinges post-Pearl Harbor, with Japanese citizens rounded up and interred in prison camps, panic and paranoia set permanently on a hair trigger, and where opportunities for vice, graft and criminal personal advancement are at an all-time high. In This Storm this already rich backdrop is enlarged further – a body long buried in a city park is washed up in a flood, while a cold-case gold robbery and a triple homicide at a club frequented by clashing clans of political extremists all look like they could be connected.

By taking characters he’s been living with for decades and throwing them into an unprecedentedly turbulent time, Ellroy has given himself maximum opportunity to weave webs and pull strings. And while there is always a temptation, with this writer of murder and mayhem more than most, to try to dig for clues to the art in the life, Ellroy is a writer of such poise and panache that the books have to be front and centre in any conversation with him.

"Writing is a wholesome process for me," he says. "It’s always enlightening, ennobling, and brings me closer to human beings, and makes me more tolerant, and brings me closer to God. I love it. I love it more than anything."

How does it work, then? What’s your set-up?

Ellroy: I love being alone, with absolutely no noise. I have a nice desk. I have a landline telephone. I write by hand. And I love putting words on paper. I love thinking. I love pondering.

When I’m putting a book together, which is what I’m doing right now back in the states at home, it’s like there’s a big screen – movies from the early 1960s, when they made movies in Panavision and black and white. And I’m moving the criminal stories, the political stories, the love stories, the police corruption stories through my mind, fitting the elements together in the weeks and months.

I can’t tell you how much time I spend just thinking: "Okay. Okay. What’s the point of convergence with the gold robbery and the Griffith Park fire?" Which was a real thing. "Is there too much backstory? When do I set the murder at the clubhouse? That coming in 40 chapters into the book – how’s this going to work? When do I reveal this? When do I reveal that?" And then all of this becomes almost like a novel unto itself. It becomes the outline. And from there, the book. So, I’m really writing the book twice. Which is why there’s these gaps between my publications.

The style seems to be evolving.

If you go back two titles to Blood’s A Rover, I’m expanding this style. There’s a reason for this. It’s to enhance the emotional language. That poor kid [in Blood’s A Rover], Don Crutchfield, in love with the left-wing revolutionary woman; Dwight Holly and the doomed love between him and Kathy Sifakis. It’s interlocking love stories in history, and the style had to be expanded.

It’s more expanded in Perfidia, and there’s the break point of an entirely new style with Kay Lake’s diary. And it’s yet more expanded in this book. If you were to examine it, sentence to sentence, it’s still so dense that it feels tightly compressed. But I have gone over, and over, and over the text in order to properly expand it and enhance that text.

Some people have said the style can get in the way.

If they’re talking about White Jazz and The Cold Six Thousand, I’d agree entirely. Now, I think it’s its honed and refined and mastered to the proper degree. People have told me this is the book which is the heaviest in back story. And people that I trust absolutely have told me the plot is entirely comprehensible because of the reduced usage or deployment of the style.

A key part of this process is melding the fiction with the historical background.

Publishing has taken some hits financially with the internet and everything. And fiction is down – non-fiction has spiked way up. People are always on the internet. They like the concreteness of non-fiction because it purports to tell them about their life. Well, the novel is entirely about that. If you can submit yourself to the novel and realise that, physically, it has nothing to do with you – Los Angeles, the home front, early World War II, a corrupt cop, a Japanese forensic chemist, a boozed-out Navy nurse, rogue cops, and everything else – but it has everything to do with human beings and how they grasp, and how they love, and how they fall, and how they transcend. You know, it’s "The Novel", with a big capital T, and a big capital N. That’s what I’m out to give the folks.

What do you enjoy more – is it the spinning of all the various plates and keeping everything up there until the time is right to bring it all crashing down? Or is it the characters that you enjoy writing?

A lot of people write books; long books. And I doubt if anyone today – or perhaps ever – has written books as complex and layered as these. But then again, I doubt if anyone that you might call a crime writer has written these massive outlines. I’m a professional. I’ve been doing this for 40 years. And If you look, the intervariances in language, viewpoint to viewpoint: the way people speak – since these were all subjective third-person viewpoints; the way that they elaborate their thoughts, especially in the chapters that carry large pieces of time and jump the story – you see how I do it. It’s the attention to detail.

Is that what you live for in your writing?

I live to write the great finish to the book. I strive for perfection in language, characterisation, and the rewriting of history.

How real are these people to you? I mean, you carry them around with you everywhere, and you’ve been inside their heads for such a long time. Do you like them?

Yeah. I love them all, and I love the characters in Perfidia and This Storm most of all because these are my books about egalitarianism, inclusiveness, and the police world that I’ve been adopted into. I’ve never wanted to be a policeman, but I love them as a breed of men and women. And it’s the world that they live in, as shitkicking Americans in 1942.

There are these very, very deep friendships, and these people united in a common cause – an allied victory in the War – and the internal fortunes and the infernal factions of the Los Angeles Police Department. The whole theme of friendship is very, very strong. Walls collapse: social walls, racial walls collapse in World War II. Dudley Smith’s only real friend is a Japanese homosexual. You know?

Hideo Ashida is the guy that he reveres, not his goons, Breuning and Carlisle, or his women, who are really his victims, or his numerous daughters, who were just a flounce of his stupid Irish sentiment and bullshit blarney.

The extremes the characters pitch for range right across the political spectrum. Should we be reading these as maybe not a plea, but perhaps a hymn to or an elegy for moderation?

Yeah. Well, for freedom, for decorousness, for lucid thinking when confronted with the extreme political pulls that do nothing but play on one’s emotions, as they seek to delude and convert and create horror.

I know you decry any relevance or resonance to the present day, but that seems like a theme that’s particularly needed today, in what feel to many of us like increasingly polarised times.

I understand what you’re saying. It wasn’t my… I conceived the book before all this hoo-hah and the present day commenced. I conceived this book and outlined it. I mean, I knew the book in its entirety. It’s not meant to be topical. It’s meant to be read… It’s an instructive novel, and it doesn’t instruct you what to think about the world today.

The message for people today is: "Here is a complex, dense work of art, and I want you to read it. However you consider it to be relevant in your own life today is up to you, and I’m not going to tell you how to think," which is why I give people no cues along the lines of the contemporary.

People need to be taught how to read. [points to people staring at cellphone screens] It’s not that important – whatever it is can wait until you get to a payphone. Fiction’s in the tank because people are used to reading the internet, getting scattergun bursts of information that they immediately relate to their own lives. "I’m going to find my next sexual partner on the internet. I’m going to buy my next article of good clothing that will help attract my next sexual partner on the internet. In the music world, I’ll get some good compact discs, obscure, for three bucks apiece, and they’ll be shipped out of Amazon to me, and arrive at my door in a couple of days."

It’s crazy to me, that people don’t want to be transported in the interactive art of reading, to another place, another time, that they’re attracted to because it’s dissimilar, it’s a world they couldn’t have imagined.

You talk about your fondness for police in general, and the LAPD in particular, and your ongoing friendships with people in that world – yet the majority of the LAPD officers you write about are very difficult to like. Elmer Jackson is among the most sympathetic, but he’s basically a pimp and a womaniser; as a reader I find myself liking Buzz Meeks, but it’s despite his tendency to extract information from suspects through violence.

If you look at the guys they’re thumping on, by and large, they’re bad. They deserve that. I’ve known some cops that did some thumping that they shouldn’t have done, in order to put some very bad guys, as in rapists and child molesters, behind bars. So the question I always ask people is: "If you were in their shoes and your choices were to put the phone book to some child molester or rapist to secure a conviction, what would you do?"

It’s a real tough question to answer, especially back at a time when there was really no legal redress for this kind of abuse of power. It’s 1942 here. All bets are off. And in the meantime, these guys love and lust, and pine for women, and everything else.

Cops are the most romantic people I’ve ever met, and LA cops are some of the sweetest-natured and most sentimental people I know. I was trying to explain to someone asking me a question last night about the books, myself, and everything. I said, "Look, I’m an American, I’m patriotic, I’m conservative, I’m religious, and I’m sentimental. I see the world realistically and I see human beings realistically. The people that carry that weight – in the end I can forgive them." Even Dudley Smith, who is piece of shit who should be stopped at any and all costs.

You’ve said that you have no particular interest in writing anything set later than 1972 [the end-point of Blood’s A Rover]. Why is that?

More than anything else, it’s a blind instinct. I want to live in the language of the ’40s. There’s a lot of very funny stuff in Blood’s A Rover with Nixon and Hoover there, trying to talk hip, tell it like it is, and everything else in the late ’60s and early ’70s. I lost the idiom about then.

I enjoyed the idiom in the black pimp movies that I saw. I liked the black comedian shtick, that guys like Reynaldo Rey and Richard Pryor were doing. But the language from that point on, I don’t give a shit. I don’t want to go there.

Yet you’ve done work for film and TV that’s set in contemporary times: there was the movie Rampart, and an as-yet-unmade TV series called Gemstone…

All that shit, these were paychecks, and they’re long gone. They just dropped off the face of the Earth. Rampart, there’s virtually nothing I wrote in there. I hate the movie. I hated Woody Harrelson’s performance, and it was rewritten out from under me by Oren Moverman, the director. It’s a bad movie, as is Dark Blue, which is a Ron Shelton movie. It was originally my script, The Plague Season.

The other movie that got made, Street Kings with Keanu Reeves – that was something that I wrote really for Nick Nolte. I made a bunch of dough, and it financed my divorces, you know? Paid alimony, taxes, and shit like that.

Hollywood has been good to me in that regard, but it’s over. It’s very unlikely that there will ever be a film made from anything that I’ve written because the characters of Perfidia and This Storm are tied up legally with the film versions of The Black Dahlia and LA Confidential. Kay Lake, Dudley, all of them.

I made the decision, not long ago, just not to do any more film and TV work. I only want to write novels from hereon in. I’m 71 now, and I’m healthy. I really want to write a total of five more books. Two books in this quartet, and then a new Underworld USA trilogy.

How’s the third book of this quartet shaping up?

Kay Lake is the overall hero of the whole second LA quartet. The important thing with Kay Lake is she acts in the heat of the moral moment, and she acts purely. She’s not doing a diary viewpoint in the next book, but I’m reasonably certain that she will in the fourth book.

I started thinking about the next book about halfway through [writing] This Storm. Right before I left for Britain, I read a book about the 1932 Lindbergh kidnapping – the kidnap and murder of the Lindbergh baby. And there’s a character, a real-life psychiatrist, that I realised I wanted to use in the new book in a backstory, for a US treasury agent – because they captured the killer, Bruno Richard Hauptmann, a German immigrant, by tracking the serial numbers on the ransom bills. So, I’ve been teething on that for a couple of weeks. And then I got on the airplane.

What about the second Underworld USA trilogy – where will that go?

I have ideas, but I don’t know yet. It would be back in time. I think 1956. But this is just the beginning of thinking about it.

And at the rate that you write, it could be a while before we get there.

Oh, brother! Yeah, I know.

You’re going to be about 90.

One hopes! From your mouth to God’s ears.

This Storm by James Ellroy is out now, published by William Heinemann