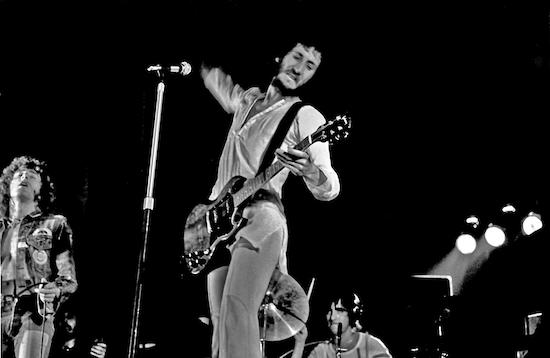

Photo by Heinrich Klaffs, CC BY-SA 2.0

On 9 September 1966, The Who’s appearance at the Pier Pavilion, Felixstowe, was filmed by French television. The recorded songs are compressed into a montage of clips that concludes with a version of ‘My Generation’ featuring a long feedback coda. The end sequence focuses on Townshend, with brief cutaways to Daltrey and to Moon adding to the maelstrom. The noise is ferocious but given shape by Entwistle’s throbbing bass line and Moon pounding on the one floor tom-tom left standing. Townshend places his back against his two amps and speakers, and with arms outstretched he uses his whole body to modulate the feedback. He flays the guitar, slashing out Bo-Diddley-esque runs before turning his back to the audience and spearing one of the cabinets – jabbing the guitar’s headthrough the mesh and into the speakers. Facing front, he machine-guns the camera, he retreats once more into the backline and rams the guitar’s body into the stack. The performance is thrilling. The Who produced an immersive, inescapable spectacle and sensation – an attraction that defied any alternative or substitute – which cannot be denied.

The Stooges’ guitarist, Ron Asheton, recalled a 1965 visit to England he made with fellow band member Dave Alexander. Setting themselves up in Liverpool, they went regularly to the Cavern Club where they witnessed The Who’s only performance at the home of Mersey Beat:

It was wall to fucking wall of people. We muscled through to about ten feet from the stage, and Townshend started smashing his twelve-string Rickenbacker. It was my first experience of total pandemonium. It was like a dog pile of people, just trying to grab pieces of Townshend’s guitar, and people were scrambling to dive up onstage and he’s swinging the guitar at their heads. The audience weren’t cheering; it was more like animal noises, howling. The whole room turned really primitive – like a pack of starving animals that hadn’t eaten for a week and somebody throws out a piece of meat. I was afraid. For me it wasn’t fun, but it was mesmerizing. It was like, ‘The plane’s burning, the ship’s sinking, so let’s crush each other.’ Never had I seen people driven so nuts – that music could drive people to such dangerous extremes. That’s when I realized, this is definitely what I wanna do.

The extremes described by Asheton were never an end in themselves. Reports of The Who’s 1965 tour of Scandinavia underscore the serious intent of the band to do something other than simply entertain their audience. It became a commonplace in Denmark to describe their music as ‘pigtråd’: ‘like having barbed-wire pulled through your ears’. One critic likened the noise made by the band to a ‘massacre’ and, out of the turbulence, The Who ‘create sounds we’ve never heard before’, using an ‘established music language’ through which they channel ‘their complex ideas into practice with an astonishing artistic straightforwardness that touches people . . . The act, exciting and passionate, is performed without losing control over the performance as a whole.’ The writer concluded with the thought that the show could only be bettered if the guitars and the building they were playing in would go up in smoke ‘backed by the shout of joy from the audience. Indeed – The Who is anarchy!’

In this view from Denmark, The Who appear to be dancing on the ruins of civilization, enacting an echo of F. T. Marinetti’s Futurist summons to ‘take up your pickaxes, your axes and hammers and wreck, wreck the venerable cities, pitilessly.’ Whatever the modernist reverberations The Who were responding to, they were consciously engaged in parsing elements of avant-garde practice through their live performances.

The glee to be found in destroying objects was something he did not deflect attention away from; Townshend’s actions are never simply defined by him as joyful unfocused moments of vandalism. The film director Michelangelo Antonioni, unable to secure the services of the band, featured The Yardbirds in their stead and had them mimic The Who in a club scene in Blowup (1967). Jeff Beck destroys his guitar and throws part of it into the crowd. Fighting others in the audience, David Hemmings’s character Thomas takes ownership of the guitar neck. In the moment of struggle, the desire for possession is everything, but thereafter the fragment of the instrument is emptied of meaning and value, and is tossed away. In his art and in his rhetorical utterances, Townshend recognized this state of affairs. He knows that desire cannot be satisfied, and so he sought jouissance – a transgression of the prohibitions on one’s pleasure – in order to go beyond the base juvenile delight in smashing up things that others value.

Explaining why The Who had not appeared in Blowup, Antonioni said: ‘What the Who do is too meaningful. I wanted something utterly meaningless, so I could use them.’ The wreckage and havoc in a performance by The Who was conceptual in its planning and enactment. It was not pointless, it was not simply an empty spectacle that Antonioni could exploit. The Who’s aggression

was being channelled through the practice of auto-destructive art as theorized by Gustav Metzger, whose ideas were given public shape

in his 1959 manifesto and more intimately in the classes he taught

at Ealing Art College, which Townshend had attended. Metzger described his art as anti-capitalist, anti-consumerist and anti art-market. In turn, Townshend’s enactment of Metzger’s theories

was neither superficial – a marketing pose or a throwaway association – nor were they held by him without serious qualification.

When I was at art college Gustav Metzger did a couple of lectures and he was my big hero. He comes to see us occasionally and rubs his hands and says, ‘How are you T?’ He wanted us to go to his symposium and give lectures and perhaps play and smash all our equipment for lira. I got very deeply involved in auto-destruction but I wasn’t too impressed by the practical side of it. When it actually came to being done it was always presented so badly: people would half-wittedly smash something and it would always turn around so the people who were against it would always be more powerful than the people that were doing it. Someone would come up and say, ‘Well, WHY did you do it?’ and the thing about auto-destruction is that it has no purpose, no reason at all. There is no reason why you allow these things to happen, why you set things off to happen or why you build a building that will fall down.

With his embrace and criticism of theories around auto-destructive art, Townshend had shifted the terrain across which the band roamed. Pop iconography was now the least of their preoccupations. Furthermore, the direction of influence and theoretical borrowings was not simply one way, from art theory to Pete Townshend. In 1965, another of the tutors who had taught Townshend, Roy Ascott, brought a copy of ‘My Generation’ into his class, which left a lasting impression on one of his students: Brian Eno. David Sheppard, Eno’s biographer, writes: ‘This was pop music with its art school slip showing, as invigorating as it was emancipating. At a stroke, its three minutes of febrile, distinctly British musical energy convinced Eno that contemporary art and music could legitimately cohabit.’

Alongside Metzger, Ascott was part of the organizing committee for the Destruction in Art Symposium held in London in September 1966 (this is no doubt the event Townshend said Metzger had invited The Who to participate in). The symposium was widely publicized and Antonioni would surely have been aware of it when he shot the Blowup sequence with The Yardbirds thefollowing month and, probably, equally sure he did not want his film to open up the debates being called for by Metzger (and practised by The Who). ‘There will be burning of book towers in London this month,’ wrote The Guardian’s art correspondent, ‘there will be evisceration of type-writers and a dissonance of pianos going to their death. There will be floods of molten metal and a day-long event dedicated to throwing the end product away. All this and lectures too.’ The sonic side of the event led by the American artist Raphael Ortiz, was dedicated to the destruction of pianos with microphones attached, ‘so that everyone can hear what it sounds like. Music after all, is the result of arbitrary decisions on what sounds should string together. Mr Ortiz wants to return to the basic sound, and so he destroys pianos.’

Throughout the 1950s and well into the 1960s, independent of any urbane, art-world sensibility, pianos were being routinely destroyed by the score at village fetes, town fairs and as part of an evening’s pub entertainment. These heedless acts were conceived as a contest between teams to see who could most quickly obliterate the instrument so that all its parts could be passed through a small hoop. One bourgeois witness to such an event writes how horrified he was:

to see two teams of grown men wantonly laying in to two defenceless uprights, to see felted hammers flying everywhere, tangles of springy piano wire, splintered wood and the black and white ivories lying slaughtered on the green grass. Now, years later, I think that it was possibly also a symbolic act, the ritual destruction of repressive Victorian values, embodied in the piano, which deserved to be taken out on to the village

green by right-thinking English yeomen and smashed. Decades of primness, prudery and piety in the parlour, of hypocrisy and violence, of empire, wars and colonialism. All this projected on to the piano, around which families prayed and sang hymns and parlour songs of fervent faith and patriotism. But the craft that went into an upright piano! All gone in a twinkling. And a tinkling. How very sad it was.

The domestic piano had become redundant (and worthless) with radio, phonographs and television dominating home entertainment. Whatever the symbolism of such wanton acts of destruction, the smashing of pianos was widely practised as a working-class pastime, not a middle-class art project. Elsewhere, in the world of entertainment, when the need arose to upstage another performer, Jerry Lee Lewis had shown he also held a similar disregard and lack of respect for his instrument. Townshend’s wilful wrecking of his guitars and amplifiers was taking place at the interstice between Metzger’s art, class resentment and rock ’n’ roll’s performance of stylized violence.

In 1968 Townshend told the BBC’s Tony Palmer he had written a ‘thesis for Gustav Metzger’ on pop, art and violence, but by then he hardly needed to make the point that The Who were about more than being a pop group. On the last day of 1966, the circuit between Ealing Art College, auto-destructive art, Metzger and Townshend, between pop and art, was closed when the artist provided a liquid-crystal light show for the New Year’s Eve Psychedelicamania event at the Roundhouse in north London. The Who, The Move and The Pink Floyd shared the billing. The Move’s set climaxed with the smashing of TV sets and a car. The Pink Floyd performed their extensive jams hidden deep in the shadows. The Who suffered from power failures, distracting strobe lights, and ended their set in a full-on rage of destruction. Not everyone was impressed by these displays of masculine aggression. Frances Gibson, a Royal College of Art student and guest reviewer of the pop scene for Queen magazine felt that, ‘Such wasteful energy as The Who and The Move advertise seems very much like small boys’ tantrums.’

No doubt in thrall to masculine display, other guitarists paid homage to what Townshend was doing – Eddie Phillips of The Creation used a violin bow to turn the sounds his guitar emitted into something akin to the rumble of a diesel engine; Jimi Hendrix embraced pyrotechnics – but none found the violent seam that Townshend mined with such splendid, juvenile glee and insouciance.

When Jeff Beck attacked his amplifier and smashed his guitar in Blowup it was in response to the instrument’s malfunctioning; when Townshend rammed his guitar into his speaker stack it was done with the aim to create noise. He is not executing an intuitive action, but doing something that is intended to be provocative and that has the power to attack the listener: ‘Pop music is ultimately a show, a circus. You’ve got to hit the audience with it. Punch them in the stomach, and kick them on the floor.’

It is within the realm of sound that The Who are at their most radical; not copyists but innovators. The Who’s dedication to immediacy, to the moment, to living in the present tense, produced animpatient pursuit of the new in the now. ‘This is what art is; this is what our music is all about,’ said Townshend in 1968,

It involves people, completely. It does something to their whole way of existence, the way they dance, the way they express themselves sexually, the way they think – everything. But most importantly our music tells you about now. Ultimately there’s nothing left but the present.

Because he believed in the ‘now’ of pop music, Townshend showed complete disdain for all that The Who had achieved and for the others on the scene who were less fleet of foot in taking the initiative, less agile in grasping what moved before them. Dismissing the pursuit of quality as a worthwhile goal in and of itself, Townshend told a January 1966 television audience that he was ‘more interested in keeping moving. I think quality leads to being static.’ His desire to live in the present was propelled by an intensity that gave the appearance of someone who was witness to, and a participant in, an accelerating, exaggerated and unpredictable world:

My personal motivation on stage is simple. It consists of a hate of every kind of pop music and a hate of everything our group has done. You are getting higher and higher but chopping away at your own legs. I prefer to be in this position. It’s very exciting. I don’t see any career ahead. That’s why I like it – it makes you feel young, feeding on insecurity. If you are insecure you are secure in your insecurity. I still don’t know what I’m going to do.

Through the language of negation, The Who amplified their non conformist aesthetic and pushed it beyond that used by the posturing of their rivals. When Townshend said ‘ours is a group with built-in hate,’ he was defining The Who against both the pop mainstream and their immediate competitors; until the appearance of the Sex Pistols in 1976, The Who alone on the British scene spoke in such terms.

Velvet Underground founder, the Welshman John Cale, recalled the formative effect that The Who’s recordings, alongside those by the Kinks and the Small Faces, had on him and Lou Reed: ‘They were sniffing around in the same musical grounds that we were . . . their guitarists were using feedback on records. It made us feel . . . we were not alone.’ Cale conceived of the Velvet Underground in remarkably similar terms to those held in 1965 by Townshend: ‘We were in it for the exaltation,’ Cale wrote, ‘and could not be swayed from our course to do it exactly as we wanted . . . We hated everybody and everything . . . We did not consider ourselves to be entertainers and would not relate to our audience the way pop groups like The Monkees were supposed to; we never smiled.’ In the lifeless urban landscape on the cover of the My Generation album no one in The Who is smiling either.

A Band with Built-In Hate: The Who from Pop Art to Punk by Peter Stanfield is published by Reaktion Books