Sometimes it’s hard to believe that Mark Hollis didn’t script the entire story in advance: Talk Talk’s tale is, in many ways, the reverse of what happens with most bands that become successful. They didn’t start out making difficult music, slowly winning over an audience with their brave, critically acclaimed steps into the unknown before drifting into the mainstream, their rough edges softened by the necessity to survive at the top, their musical ambitions sacrificed to commercial interests.

Nor did they work their way up the ladder with endless touring or allow themselves to be pimped to the marketplace until they became so ubiquitous that they could afford to rest on their laurels and revel in the rewards that those who play it safe get to reap. Instead, they began by making pop music of an apparently commercial kind, charting in their home country’s Top 20 with their third single, enjoying considerable international success with their second album, and going supernova with their third.

Then they retreated into a world of shadowy, sublime but distinctly complex music that alienated many of their fans, before refusing to tour altogether, suing their record company, antagonising their new label and splitting up. In the years that followed, the band’s members released little music of their own, and their leader – the aforementioned Hollis – disappeared from public view entirely, refusing all interviews after his only solo album hit the stores seven years after their split, leaving a void in which only speculation and mystery could survive.

This is how legends are born. Not the kind of legend that allows an act to fill arenas and forces them to set up offshore bank accounts. Not the kind of legend that ensures that each album of pale imitation is greeted by reviews which trumpet “a return to form”. And certainly not the kind of legend that ensures that every utterance earns them headlines, enabling them to sway public opinion on political, social or environmental matters. No: Talk Talk are the kind of legend that matures with age, the lack of information and explanation enhancing their inscrutable status as uncompromising pioneers, the unanswered questions contributing further to the mystery of how and why they pursued their remarkable, fanatical journey towards a sound that no one has ever quite managed to replicate or classify. They’re the kind of legend whose reputation is built almost entirely upon their music.

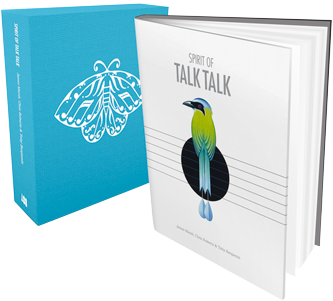

Now, after almost fifteen years of silence from the band’s central figure – production of two tracks on Jan Garbarek’s daughter Anja’s 2001 album, Smiling And Waving, notwithstanding – come the inevitable book and tribute album. That they’ve taken so long to arrive is perhaps a surprise, given the exponential rate at which Talk Talk’s stature has grown over recent years: they’re cited by other acts with increasing frequency, referenced by reverential critics on a regular basis, and their songs have been compiled on Best Of albums countless times in order to milk a cash cow that had formerly refused to be corralled.

The problems begin, however, with the fact that none of the band’s members have participated in the publication of Spirit Of Talk Talk (the book’s website is here), meaning that it’s left to The Quietus’s Chris Roberts (over the book’s first eighty pages) to gather information already available in order to piece together their history while trying to encapsulate their musical appeal and influence. Another fifty pages of personal impressions concerning the band’s music, delivered by a diverse selection of ‘talking heads’, confirm that they continue to hold a wide range of musically inclined individuals in thrall, and a third section allows illustrator James Marsh to discuss the idiosyncratic artwork that he provided for almost every single record the band released.

But interviews with session musicians, an engineer on their third album and the man responsible for EMI’s handling of the band’s catalogue are hardly required reading, and nor is a reprint of a less than revealing questionnaire the band filled in for Look-In magazine. The full transcript of Mark Hollis’s final interview (with Rob Young, author of Electric Eden and editor-at-large of The Wire) is perhaps more valuable – but even this sees questions longer than answers, leaving only a discography and a significant number of pictures and items of memorabilia to justify a price tag of £40 (for the classic edition) and a mighty £150 (for the deluxe edition).

It is a labour of love, of course, beautifully designed and packaged to complement the band’s own work. However, those already fascinated by the band and looking for further enlightenment are likely to be disappointed. To be fair to Roberts – one of the country’s best, if underused, music writers – the book never sets out to be an in-depth critical assessment of the band’s output. And if, as the cliché goes, writing about music is like dancing about architecture, then writing about Talk Talk, especially their last two albums, is like synchronised swimming about the stars in a pool of mud.

It is a point even Roberts concedes, saying of their final album, Laughing Stock, that it’s “one of the toughest albums to describe…” before simply stating, “it is righteous”. Fortunately, while his descriptions of the music are unusually restrained, he does an impressive job of piecing together their biography from the fragments of information he has collected. He also succeeds in drawing attention to their early work’s strengths, often overlooked in favour of the music that followed, even if he is at times a little defensive, unwilling to admit that it wasn’t as ground-breaking as perhaps we’d like, and suggesting a little over-excitedly that, in comparison, their contemporaries, Duran Duran, were merely “sub-glam pop-tartlets”. Still, while he doesn’t reveal anything especially revelatory, he does marshal together pretty much everything that’s known about the band into one place, and fleshes out the narrative satisfactorily. In the circumstances, perhaps we should expect little more.

James Marsh’s contribution is maybe more illuminating, given that the band chose early on to present themselves to the world in as obtuse a fashion as possible. A friend of their manager, Keith Aspden, and a designer and illustrator of books, records and advertisements since the mid 1960s, Marsh was tasked with creating art that captured the band’s music in an original and effective fashion. As time passed, his work became increasingly singular and far from predictable, especially as the complexity of the group’s music developed. The covers said nothing about the band, and yet somehow defined them perfectly. Marsh’s recollections of his methodology are therefore intriguing, and shed a great deal of light upon how a band’s image can be created, reinforced and controlled.

To begin with, Talk Talk’s early synth-pop was reflected in the Hunky Dory paper, airbrushed Athena poster stylings in which their records were packaged. But, over time – and perhaps with Marsh’s growing familiarity with the journey upon which the band had embarked – it added an extra dimension to their craft. The subdued autumnal tones of The Colour Of Spring‘s cover, with its striking, delicate moths, hint at the fragility within, at the music’s far more organic qualities, and at the metamorphosis which the band were undergoing. His images for the final two albums, often thought of as a pair, are equally fitting: Spirit Of Eden depicts a solitary tree emerging from an empty ocean, draped in shells and providing sanctuary for sea-birds, while Laughing Stock repeats the motif; the tree’s leaves now shed, its branches filled with endangered birds, the earth beneath it scorched. These covers don’t immediately tell you much about what is contained within – and yet they match the music perfectly. That Marsh achieved this often without anything other than an album title, as he explains, is testament not only to the power of his and the band’s imagination but also to our own.

Less valuable are the contributions from fans of the band who try to articulate why Talk Talk’s music continues to flourish. These days, endorsements are sometimes the only way to cut through the superlatives of a world dominated by marketing: we trust the voices of those we respect, and there’s a certain pleasure to be gleaned from knowing that we share a passion with folk as diverse as Robert Plant, Guy Garvey and Mark Radcliffe. Unfortunately, there perhaps isn’t much to be gained from the input of such lesser luminaries as Toad The Wet Sprocket’s Glen Phillips, David ‘Kid’ Jensen or Pink Floyd keyboardist Richard Wright’s daughter, Gala, let alone the webmasters for Talk Talk’s fan site and Facebook page or a slew of musicians whose reputation is so slight as to fall worlds short of ‘cult’ status. These merely suggest the motivation behind its existence is less to provide something that seeks to answer the many questions that committed fans have about the band, and more to fill enough pages to transform this from a softback pamphlet into a coffee table book whose physical weight matches the music’s density even when its pages can’t.

Released the same month, Spirit Of Talk Talk – the album – is a double CD of cover versions compiled by Toby Benjamin and former Depeche Mode/Recoil synth player Alan Wilder. Tribute albums are notoriously difficult to pull off – I should know, having attempted one of my own to celebrate the work of Lee Hazlewood – and sympathy should always be extended to those who try to navigate the minefield of band schedules, budgets and rights. So, like the book, the compilation is flawed, perhaps due to its ambitious intent to offer thirty interpretations rather than simply a single album’s worth. But there’s another issue at stake here, in that, when people refer to songs, they often fail to distinguish between writing and performance, and there is a crucial difference between the two: a great piece of songcraft will always be a great piece of songcraft, whether it’s butchered or beautified, but a great performance can rarely be outshone. It stamps a definitive identity on a song.

Talk Talk wrote great songs: this compilation is a splendid reminder of that fact. But they were also an extraordinary bunch of musicians who cannily surrounded themselves with further great players and a manager who somehow preserved their integrity as their intent shifted from great music to great art. To attempt to match them at their own game, let alone beat them, is dangerous, especially when referring to later work. While it’s not so true of the earlier material, most of their releases after 1985 featured recordings where the songcraft and the performance were inseparable, inextricably intertwined, and the results were transcendent. Covering Talk Talk is therefore as fraught with the likelihood of failure as covering My Bloody Valentine – the originals contain a secret ingredient, so one’s only hope is to come up with an entirely new recipe that doesn’t even try to compete.

Nonetheless, there are valiant attempts, like Lone Wolf’s opening interpretation of ‘Wealth’, Bon Iver drummer S. Carey’s ‘I Believe In You’ – a song that has always seemed impossible to cover but which he interprets with subtle sophistication, as does Arcade Fire’s Richard Reed Parry at the album’s close – and Nils Frahm, Peter Broderick and Davide Rossi’s dewy-eyed take on the oft-forgotten but majestic B-side, ‘It’s Getting Late In The Evening’. King Creosote’s brave conversion of ‘Give It Up’ into an accordion-led waltz is also commendable, as is Duncan Sheik’s transformation of ‘Life’s What You Make It’ into an acoustic lament. In addition, Joan As Policewoman takes a worthy stab at ‘Myrrhman’, and Do Make Say Think emphasise the stratospheric magic of ‘New Grass’ with some success.

But always in the background is the distant, haunting echo of the originals: Hollis’s remarkable voice, the innovative arrangements, the hauntingly engineered sound. As a result, many of these readings sound at best like failed attempts to breathe life into something that never needed resuscitation. Zero 7’s ‘The Colour Of Spring’ twinkles but still sounds like a soundtrack to a soap commercial; Zelienople’s attempt to reduce ‘The Rainbow’ to a sparse, droning soundscape is deeply troubling; The TenFiveSixty’s ‘It’s My Life’ sounds like it was commissioned by a Hollywood film director to soundtrack a club scene with an edgy, Barbie Doll-fronted band in torn jeans and tight T-shirts and renders No Doubt’s version – against all the odds – bearable; and Turin Brakes’ whiny, trebly ‘Ascension Day’ may make the original impossible to enjoy ever again. Like the book, the tribute album sheds little new light on its subject but, then again, arguably neither actually attempts to do that. They are celebrations of Talk Talk’s work, after all, and both succeed in erecting huge signs back towards the stuff that inspired them: the band’s original recordings. The question is whether they’re entirely necessary.

Talk Talk are now pretty much established amongst the canon of undervalued and yet vital acts whose influence grows with each passing year and for whom respect cannot fail to continue growing. They are, despite the restrictive synth pop sounds of their juvenilia, very close indeed to being filed alongside the likes of Nick Drake, My Bloody Valentine, Can, David Axelrod and Lee Hazlewood – I, of course, would say that – and they are on the cusp of joining (if they haven’t already joined) the list of artists whose work is spoken of in hushed tones by those who truly love music and are prepared to step beyond the boundaries of the known. Neither Spirit Of Talk Talk (the book) nor Spirit Of Talk Talk (the double album) is capable of capturing the elusive, mysterious, alchemical qualities that made Talk Talk’s work and recordings so frequently, immaculately perfect. But if they turn people on to the idea that even the quietest music, even the most superficially simple songs, even the biggest hits and the least successful of albums, can contain depths that our current listening habits prevent us from recognising and that we should nonetheless explore, then they have proved worthwhile.

Their existence, however, is likely to be forgotten long before Talk Talk’s. Prophets may rarely be recognised in their own time, but their disciples are rarely remembered at all. Talk Talk’s music has become a religion of sorts, and their legend keeps on growing, with or without artifacts such as these. Despite Mark Hollis’s and Talk Talk’s claim that they had always intended to make music as challenging as that with which they ended their existence – Hollis is often said to have attributed the band’s early use of synthesisers in place of real instruments to nothing more than financial necessity – there’s no way that they could have foreseen just how far the band would journey. But, though the story of the band was far from orchestrated, it has the happy conclusion Hollis always wanted.

“I hope in the end to be understood for the music I do decide to put out and meaning and sense the music has,” he told Melody Maker’s Cliff Jones in 1991. “It’s almost useless asking me questions about it. The music speaks for itself.“

EXCERPT from The Spirit Of Talk Talk by Chris Roberts

It’s perhaps hard to convey now how thoroughly the ‘New Romantic Movement’ took over pop in the early Eighties. And how pop thus stole back some ground from rock or New Wave or what would now be called ‘indie’, suddenly and briefly becoming the go-to forum for intelligent, ‘serious’ debate and aesthetic expression. Of course, every generation brings its new thing, its ‘new look’, sometimes several. But as the Eighties dawned, this

splash of colour was shocking to some, a eureka moment to many – especially to those a dash too young to accept punk as Year Zero. A mix of chancers and romancers and in-crowd dancers soared to commercial and critical ascendancy with cutting-edge synthesizers, sharp tunes, and sharper clothes, often if not always quoting Roland Barthes as they flew. From reinvented punk-rocker Adam Ant to Islington’s kilt-sporting Spandau Ballet to Beau Brummel-worshipping Visage, not forgetting Soft Cell, Culture Club, The Human League, and a stream of lesser lights, the New Romantics dressed to kill and pressed play to thrill. As punk fizzled out, they insisted the show go on and move forward.

With MTV launching in late 1981, how you looked became almost as important as how you sounded – some would argue more so. “Ridicule is nothing to be scared of,” declared Adam Ant, and the new kids on the block donned warrior stripes, head-dresses, and gender-bending garb to prove the point. At first, the tabloids feigned outrage at men wearing eyeliner while earnest, out-moded, rock critics bemoaned the lack of ‘authenticity’, guitars, and random railing against Thatcher. Eventually they cottoned on, or caved. The era remains one of British pop’s weirdest and wildest.

It’s both easy and difficult, then, to understand why EMI saw fit to push the young Talk Talk into this boom. Easy, because they wanted another Duran Duran cash-cow. Difficult, because Talk Talk were not vacuous pretty boys. They were, it would seem, just naïve enough to go along with whatever advice they were being given by those more experienced in the business than themselves, and so their debut album was given a topical-typical sheen and loaded to bursting point, by Duran producer Colin Thurston, with tropes and techniques then in vogue. Much of the sound of the album slavishly imitates the breaking-big new bands of the time (drum pads, Fairlight sequencers), and all but disguises the fact that in Mark Hollis there was a singer of rare emotive power and a writer with a clear individual vision. As h2g2 has written, “The result sounds incredibly dated now – the motto of the production appearing to be: why use a real instrument when there is a crude-sounding synthesised version available? Only the title track and ‘Candy’ escaped with a treatment that comes anywhere close to realising the potential of Mark’s songwriting. This is one of those albums that is difficult to love, unless you loved it when it first came out.” And as Jim Irvin has opined, “The hollow airless sound of The Party’s Over, with its glutinous fake strings and clumping drums, put Talk Talk squarely in the place he [Hollis] despised most: the disposable end of New Romantic pop.”

Yet, for all those truths, some of us did love it. It hasn’t aged well, sure, and it could have lived with a guitar or two (hindsight’s a wonderful thing), but we were young(er) then and it was the sound of the times. (As were, to be fair, a Flock of Seagulls.) And always, despite the plastic rhythms and insanely frenetic fills, there is that voice – a sound apart, an emotion above.

“The Party’s Over” was of course the title of a famous Jules Styne song, first publicly sung by Judy Holliday in the 1956 musical The Bells Are Ringing, and later interpreted by Nat King Cole, Doris Day, Shirley Bassey, Dean Martin, Lesley Gore, and many others. It’s a staple of the resilience-through-melancholy genre, a not-quite-heartbroken torch song. “The candles flicker and dim… take off your make-up… it’s all over, my friend…” One can hypothesise about its appeal to Hollis.

The album of the same name opens with the self-referential three-minute anthem, “Talk Talk”, a big surge of keyboards and treated drums curling into a memorable synth motif, and the first words Talk Talk as a band were to utter: an unlikely “hey! hey!” Talk Talk were not The Monkees, but you have to give this single its pop props. The lyrics work nicely against the gregarious grain, phrases like “anxiety was bringing me down” and “I’m tired of listening to you” reiterating Hollis’s separateness from the sound of the crowd. And yet the refrain, repeating the band’s moniker, became an unwittingly productive mnemonic, an assertion of a brand name. There’s a clever breakdown of fragile piano droplets, the first glint of period slap bass (there’s a fair bit of that on the album), and a gentler third verse in which the voice is allowed to reveal its tenderness – “I’m not so blind to see that you’ve been cheating on me…” – before a robust build back into the chorus. And now every cry of ‘talk talk’ is answered by a ghostly echo: remember their name, they’re gonna live forever…

But why had Hollis named his band after one of his songs? “The track was up there round about the same time as the band was actually formed,” he told Sounds. “We went through the dictionary, had all the novels out like William Burroughs and things, and finally ended up with Talk Talk because, partly, I like the idea of a track with the same name as the band, and it’s really instant in terms of memorising it. Plus it didn’t in any way categorise us. The third reason was from a graphic point of view – it would look good. The fourth one, purely from a personal hang-up I’ve got, is that I don’t really like it when people abbreviate a name, like The Stones.”