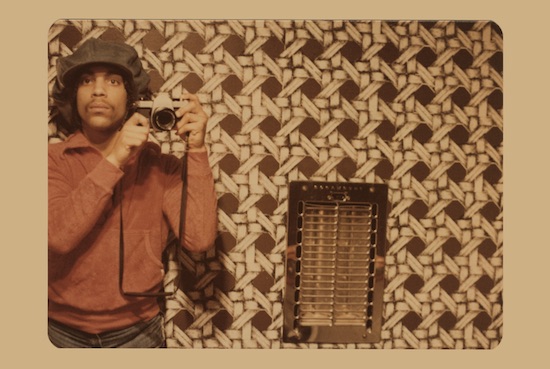

“I took this picture of the heater and I, in the bathroom mirror,” Prince wrote. This turned out to be part of a more extensive photo shoot he’d undertaken alone in the bathroom at 2810 Montcalm, wearing red leggings, cutoff jeans, and, occasionally, a fake hand. (“If you understand my color, put your hand in your crotch,” he would later sing on “Purple Music.”) © The Prince Estate

On ‘God’, the B-side of the 7 inch of ‘Purple Rain’, Prince commits heresy. He may not mean to, but his own vocal tornado carries him away. Whirring to his highest note, a B6 (he was still hitting it, in 2014, with ‘Breakdown’), warbling in tongues, Prince births welter, water and Creation. Entering God, Prince becomes God. There follows one of his most luscious oratories, darkly centred around a C chord. Finally, we land plum in Sunday School: “God made you. God made me. He made us all. E-qua-lly. Now, you sing…”

There is nothing equal about that song, nor this book.

Prince’s publishers are selling The Beautiful Ones, his partial memoir, as an “origin tale” and a handbook for artists. His co-writer Dan Piepenbring reports that Prince envisaged a “handbook for the brilliant community, wrapped in autobiography, wrapped in biography”. Prince, however, focuses on his supernatural credentials. This likely serves a Greater Purpose, but famously, appallingly, Prince died before completing his text.

The Beautiful Ones comprises twenty-seven handwritten pages by Prince. Tacked around this Holy Grail is Piepenbring’s endearingly goofy yet canny account of his encounters with Prince; a cache of Prince’s private photos, lyrics and bawdy, hand-drawn cartoons; and an early, almost disposable treatment for Purple Rain.

Prince’s publishers hunted for a diary. According to Piepenbring, they didn’t find it. “There was, however,” he writes, “plenty of evidence of Prince fighting for perfect love”.

Some might infer this means romantic affairs. This is, after all, the artist who –cooing, gasping and even ‘ejaculating’ from his guitar (Purple Rain tour, 1984–5) – did more than anyone else to sexualise rock. A few women do appear: his mother, Mattie Shaw, a capricious, affectionate and restless beauty; little girls who play house and demand kisses; older girls in “sizzler” mini-dresses. But “love” for Prince, involves a more cosmic ambition:

“Early on Eye believed another power greater than myself was at work in my life… clouds seemed like home to me… My brain has always been active and the blackouts would occur primarily from overthinking. Basically bred by the normalady (new word alert) of life… Eye always viewed it thru hyper-realities.”

Speaking here of his childhood epilepsy, Prince is a droll and psychologically acute memoirist. His hushed tone and vernacular rhythms tip-toe the reader halfway between the spotlit piano stool and the confessional box. Nothing compares to this feeling of being alone with Prince.

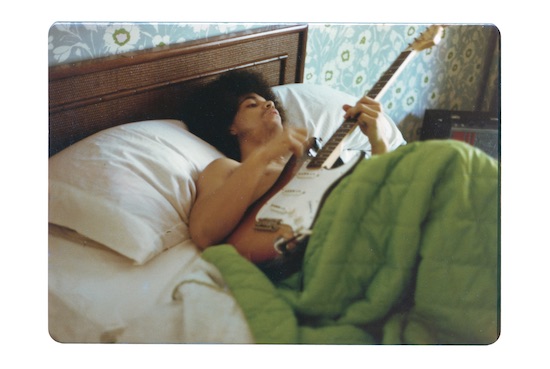

Prince plays a guitar in bed at his new home on France Avenue, April 1978. © 1986 Joseph Giannetti

Piepenbring writes that, as part of dismantling commercial white supremacy, Prince wanted to radically co-create the book with ‘Brother Dan’. Observing Prince, Brother Dan is scout-eared and eagle-eyed. But one wonders what Piepenbring’s role would have been. Prince, of course, was moulding Piepenbring: “It would be dope if, in your voice, you got scientific, fact-based – asking questions but laying down the facts about cellular memory.”

Ah. “Facts” about cellular memory. Prince is not like Dan. Nor is he like his Jehovah’s Witness congregation, whom I’ve heard preach this idea at their St. Louis Kingdom Hall. Prince is Other. He lives on clouds (or flees, in his mind, into underwater caves). He has an “octagon brain”. He cherishes feelings of flying. He slips into the collective “we” (“those considered ‘different’ R the ones most interesting to us”).

Prince’s parable tone, the esoteric script, his tales of physical collapse, are the tactics of a prophet. He talks to us as if we were children and he shows himself as a child, watching Superman. Prince’s mother uses Prince as a human shield against his father. She dumps Prince at his father’s door. Prince’s vulnerability glues us to the pew. “He has that church thing up in what he does,” Miles Davis observed. Miles opens his autobiography in a nightclub. Prince’s begins in his mother’s arms, Madonna and Son. “Eye am quite sure,” writes Prince of his mother’s habit of winking at him, “that this was the beginning of my physical imagination.”

Who is “Eye”? The book’s cover features a self-portrait by Prince in a bathroom, his camera held like an eye over an octagon-ish wallpaper print of knots. An outlined eye splurges over the ‘I’ in Prince on the album cover of 1999. Prince’s switch from ‘I’ to “eye” was formally established with LoveSexy. The first track, ‘Eye No’ deploys the same Sunday School register as ‘God’: “Rain is wet, & sugar is sweet, clap your hands & stomp your feet”.

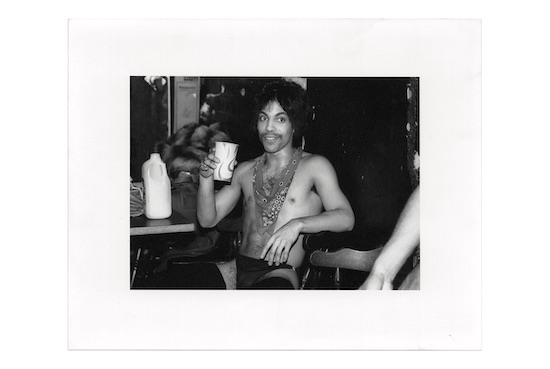

Prince sips some orange juice backstage during the Dirty Mind tour, 1981. Photography © 1985 Allen Beaulieu

Prince, like all prophets, wants his children to see as he sees. In this book, the icon of an eye embodies Prince. In the vinyl of 1999, the spindle-hole passes through a pupil of Prince’s eye. Similarly, deciphering his script makes us feel we are entering him. Those eyes, “U”s and “2”s bob among a visual jigsaw of text, photos and conversations, suggestive of Prince’s multi-dimensional vision, liberating us from “normalady”. The title of The Beautiful Ones refers, Piepenbring reports Prince as saying, to those who seek “freedom. Freedom to create autonomously,” deprogrammed from the drear world. But never deprogrammed from Prince. His character in the film treatment, published here, wants “to help people”. He notes his heresy in his father’s voice (“scoring points off God”).

His school report, aged nine or ten, also here, outlines a natural preacher, strong in discussion, considerate and entirely uninterested in listening to Teacher. As a child, writes Prince, his play tended towards “transmutation.” This is best understood in the context of the early albums that this books tries to span (For You to Purple Rain).

You can tell how funky is a musician, says Prince, by the pith and pacing of their speech. Telling his story, Prince never misses a beat. But a partition necessarily remains between him and the reader:

“Hidden places, Secret Abilities. A part of Oneself that is never shown. These r the necessary tools 4 a vibrant imagination & the main ingredients of a good song.”

Possibly, with For You, nineteen-year-old Prince may have felt he’d shown too much. But the code is there. His supernatural iconography has formed, albeit somewhat naffly. On the inner sleeve, a three-headed Prince plays guitar, naked on a satin bedspread, by an eye-shaped window. Floating in space, this Oriental god is accompanied by a childish clay dove. Prince’s nudity is a come-on and a sacrificial ritual.

More telling than the snaptight, zingy cunt-delve of Prince’s first hit, ‘Soft and Wet’, or the finger Olympics of his guitar solo on ‘I’m Yours’ is his one-man a capella chorale, ‘For You’. Here, a choir of Princes ding like wedding bells and dong like a grandfather clock. Up, down, vaulting in our ear, Prince reorganizes our minds, a harmonious discombobulation. Throughout his work, he bamboozles us, morphing one instrument into another.

After the entrancing disco LP Prince and the motorized meteor of electro-punk-funk, Dirty Mind, Prince gains in celestial hellfire with Controversy and 1999. In an ’83 interview quoted in this book, he blames this new, darker tension on disappointment in love (“love meant more to me then,” he says, of his first three albums. “I was gullible”).

Controversy is covered in mock end-of-days newsprint: “The Second Coming”, “89 Beheaded!” “Sixty Thousand New Breed Schools Built by June”. The beheaded 89 are “tourists” in life, seeing everything through a camera, instead of Prince’s quivering octagon lens. In ‘Sexuality’, his “new breed” riotously chant Prince’s gospel. There shalt be no TV nor racism. There shalt be much nakedness. The mingling of church and street preaching reaches its climax in ‘Controversy’, the Lord’s Prayer welded to a four-to-the-floor, filthy beast of a precursor to techno. Prince’s struggle, a witness to himself and to The Word (“Do I believe in God, do I believe in me?”) voices the struggle of his congregation.

In this book, the trick, so enthralling in his music, is harder to judge – but then, it’s unfinished. In the photo and “funnies” cartoon section, he’s an adorable clown, pimping up as his persona, Jamie Starr, or captioning himself sucking his cheeks: “I usually bring my teeth to the studio.” But by the time of writing these pages, Prince’s relationship with his congregation has shifted. On the surface, performing his autobiographical ‘Piano & A Microphone’ tour, he’s never been closer. But, as a Jehovah’s Witness, he ‘s moved into a philosophy of Biblical science where U may find it hard to follow our saviour – unless you’d care to join him in the church of “cellular memory”.

Prince writes, “some topics can’t b glossed over.” But he doesn’t disclose why he calls his sister Tyka “estranged”. And his rehabilitation of his father buries John Nelson’s conflicts with his adult son. Prince ascribes his skill at break-up songs to his mother’s heartbreak (“no one writes love songs like I do… the flowers are dead… the garden is dead”). We might wonder how Mattie’s subsequent mind games affected Prince’s fear of rejection by women in such songs as ‘Darling Nikki’, or the stuttering, futuristic ‘Something In the Water’ (“you think you’re special, bitch”?). But Prince doesn’t go into that.

Instead, Prince dazzles us with difference. As a child, he saw “faces in everything… Faces talking to faces… I thought, This house is coded for me. I’d lose myself in every object.” Assessing his vocal delivery of ‘Do Me’ (“flawless”), he speaks in Old Testament third person.

Prince became Prince, partly, he writes, through Vision Lists. “Looking back at those lists now, most everything came true.” By typing, writing or thinking about what he wanted, Prince tells Brother Dan, he barely aged. Speaking about his Vision Lists, Prince sounds like Genesis: “lists, stats were the 1st original writings.”

I’m troubled by the inclusion of such comments as: “I was thirteen years old and I could see everything, literally.” Printing them alongside Prince’s memoir makes scattered, spoken thoughts appear like polished text. Prince told Piepenbring he was wary of sounding self-aggrandizing. Without his music, what do we make of claims that he’s “an alpha”, or comparing himself to biblical leaders?

But then, Prince likes his children to feel overwhelmed by irrational forces. No common thinker would use that heretic song ‘God’ to score the love scene in Purple Rain where Prince caresses Apollonia’s scantily-clad clit. One of the many treats in this book, among Prince’s lyrics, is a draft of ‘1999’, opening with “I was tripping when I wrote this.” He ends his writings with a rhetorical question:

“What happens when 2 lovers stare at one another without speaking so long the separation between them disappears and they become one. One What?”

It’s an ancient preacher’s device, turning our eyes inward. Why ask questions, when U know the facts? Like his mother’s wink, Prince the prophet, in these twenty-seven beautiful, strange pages, remains open yet closed.

The Beautiful Ones by Prince is published by Century