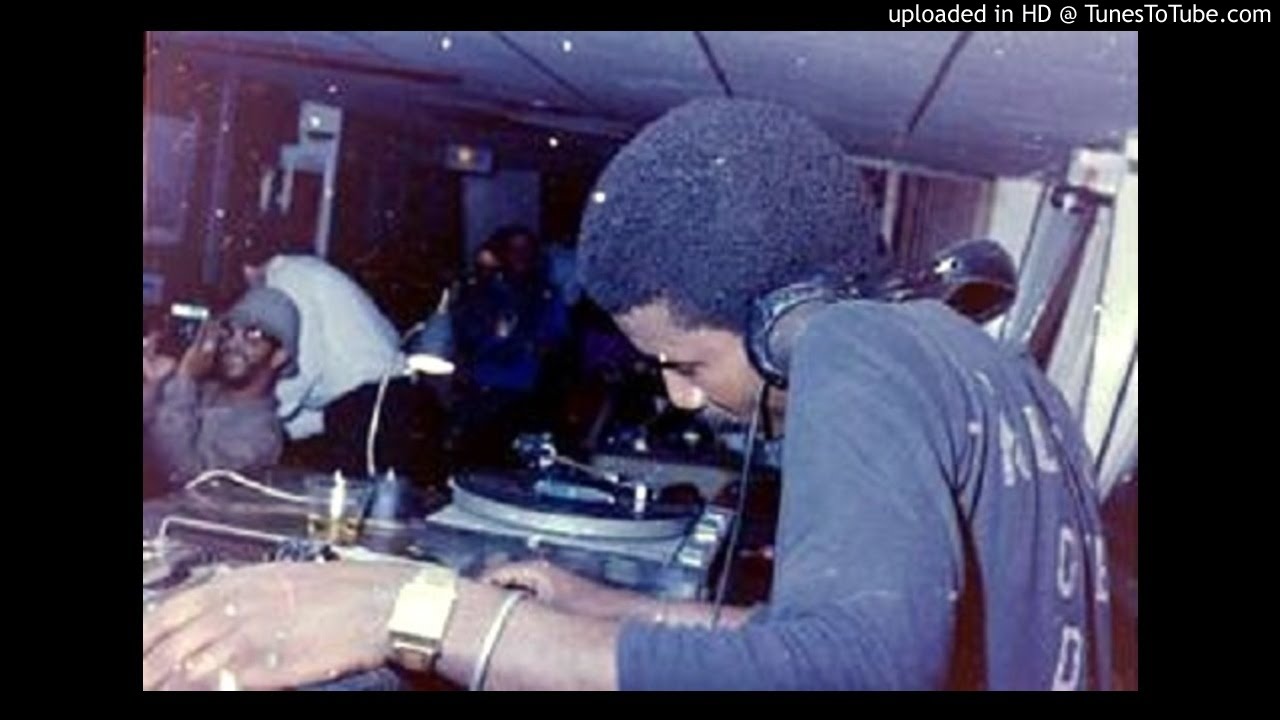

Marshall Jefferson and DJ Disciple (Photo Courtesy Of The Banks Family Collection)

“We’ve all heard about Chicago, but didn’t house music kick off here in New York?” The question came during the Q & A of a recent book launch event for The Beat, The Scene, The Sound at the New York Public Library. In the course of researching and reporting the book, DJ Disciple and I heard a variation of this question over and over.

Many DJs, clubs, and scenes want to plant their flag on House Mountain, and it’s easy to understand why. For decades, their accomplishments went unnoticed and were in danger of being forgotten. Now that we’re a year past the summer of house music, the time for recognition has arrived.

There’s just one problem. If one sets out to tell an accurate story about house music legends, it becomes clear that there is no simple, clean-cut origin story. It appears instead that there was a massive groupthink phenomenon in the 1970s and 80s where many artists developed similar techniques and styles on their own and around the same time.

Take, for example, the technique of spinning two records together in sequence. This innovation is often credited to DJ Kool Herc, the Godfather of hip hop. Some believe that it was widely practiced among mobile DJs. Grandmaster Flowers – the original Grandmaster – started off well before Herc and was known to use the same technique in the early days.

Sanctuary DJ Francis Grasso is known to have developed the technique of beatmatching in the early 70s. But Nicky Siano (early friend and collaborator with Frankie Knuckles and Larry Levan) describes developing his own beatmatching method without headphones or a cue system around the same time.

Similar stories exist for reel-to-reel cut-and-paste looping, the use of digital sound processors, mixing records with a crossover network, and many more innovations that culminated in the birth of house music.

At its root, both house and hip hop were born out of the manipulation of recorded music. DJs and producers isolated rhythm breaks and bass lines, looped and extended them, cut them up, stretched them, incorporated audio recorded from radio, TV, movies, answering machines, and added layers and layers of tonal striation until the sediment coalesced into a new musical bedrock.

Most dance music fans know how that process occurred in Chicago, Detroit, London, and New York. The dedicated heads are also aware of similar scenes in Berlin, New Jersey, Manchester, DC, Philadelphia, Leeds, Birmingham, and too many other scenes to mention.

The moments described below represent a slice of the formation of New York house music.

1. Mobile DJs

Grandmaster Flowers Park Jam — St. Marks Park, Brooklyn, 1979

It used to be that, if you wanted to be a DJ, you had to build your own sound. You had to invest in equipment and know how to wire it together yourself before you could think about song selection or mixing. In the 1960s and 1970s, the soundtrack of the five boroughs of New York was provided by mobile DJs – performers who had a unique knowledge and skill set that matched sound engineering with audio entertainment. Through this generation of DJs that laid the groundwork for hip hop and house music, one rose above the others by virtue of his skill and virtuosic sonic knowledge. Fans crowned him with a title that would soon be co-opted by MCs of later generations: Grandmaster.

Very few recordings of Grandmaster Flowers exist, and virtually all are damaged or of middling quality at best. In the sample above, taken from a jam at St. Marks Park in Brooklyn in 1979 according to the poster, Flowers can be heard flawlessly mixing the soul-jazz single ‘Boogie Down’ by Roy Ayers – later to become a down-tempo favorite of DJs like Kenny Dope and Spinna – over ‘Super Sporm’ by Captain Sky. In the recording, Flowers also brings on a range of MCs and makes good use of the echo.

DJ Big Bob, who helped teach DJ Disciple mixing techniques in his early days at the Empire Roller Rink, was a protege of Grandmaster Flowers.

“Me and my man Rodney Heath, we was into playing,” Big Bob told us. “Rodney would play the records, and I would MC and dance. On Sundays, we would always go to church. One day, Rodney comes to me and says, ‘Yo Big Bob, we got to go to Riis Beach and check out this guy called Flowers.’ We was in high school. This was ’72, ’73. So one Sunday, we didn’t go to church. We rode the bus all the way out to the beach. We got down by the courts. Flowers had four stacks set up down there. And he was banging. I thought me and Rodney had a nice set. But Flowers sounded nice. And his mix was so clean. He would go from A to Z, and you never even knew he left A.”

2. The Paradise Garage

ESG, ‘Standing in Line’

No discussion of New York dance music would be complete without mention of the Paradise Garage. The Garage was opened by Michael Brody in 1977 at 84 King Street in SoHo. Throughout the 1980s, it became the definitive dance club in Manhattan, if not the universe. Inspired by David Mancuso’s The Loft, the Garage didn’t serve alcohol and wasn’t open to the general public. To get in, you had to be a card-carrying member or know somebody who was. The vibe inside was all-accepting and, above all, safe. The primary mode of social interaction was dancing on the sprung dance floor – music played too loud for conversation over a sound system designed by Richard Long.

The DJ booth, which commanded attention from the dance floor, was helmed by Larry Levan. If turntables spinning records (hooked up to a custom Richard Long sound system) form an instrument, Larry Levan stretched that instrument’s range, timbre, and expressiveness galaxies beyond what was formerly possible.

“When I discovered the Paradise Garage, I found that it did not have the nightclub vibe that you would find in dance parties,” DJ and club owner Richard Vasquez told us. “It was more like a church. I just really felt at home. I was meeting people not because of ‘what you can do for me or what I can do for you’ but because we have the same vibe and we have the same intense interest in music. I found myself there almost every weekend from late Saturday night until early Sunday morning.”

To make a long story very short, Levan befriended Frankie Knuckles and Nicky Siano when all three were teenagers. All three developed as DJs, and all three went on to leave their own lasting marks on dance and house music. It was Levan who was initially offered the opportunity to move to Chicago to serve as resident DJ at the Warehouse.

To some extent, like the Warehouse, the dance music developed at the Garage went on to form its own genre (known as garage). But unlike house, garage classics were, in most cases, not as sonically manipulated by Levan – though he was known to make his own cut-and-paste reel-to-reel mixes and use a DeltaLab processor from time to time. His musical brush strokes, however, were primarily formed by song selection and a devotion to high-fidelity audio experiences.

Levan was also an aggressive tastemaker. Others have debated what agenda went into his selections, but no one disputes the fact that, if Larry played an unknown record, it was going to sell. If the crowd didn’t like it at first, Levan would play it again and again.

It’s impossible to choose a single garage classic. ESG’s ‘Standing in Line’, likely available as a bootleg beginning in the late ‘70s or early ‘80s, long before it was officially released on the B-side of the group’s 1987 EP ESG II, is one of thousands of tracks that Levan wove into his sonic tapestry.

The artists Emerald, Gold, and Sapphire (ESG) might as well have been formed by a group of benevolent aliens. Their unique no wave, dance-punk sound arrived in The Bronx in the late ‘70s as if through a star gate. Starting with their 1981 EP ESG, their work has influenced artists as diverse as The Wu-Tang Clan, Fleetwood Mac, MF Doom, and LCD Soundsystem. Their track ‘UFO’ has been sampled in over 500 songs, evidenced by the title of their 1992 EP Sample Credits Don’t Pay Our Bills.

3. (US) Garage

Visual, ‘The Music Got Me’

Levan’s DJing style began to influence New York artists and producers. Synth enthusiast Boyd Jarvis was an early Garage member had a day job as a window decorator. Promoter Mike Stone signed him on to help design the interior of a club he was opening, Melons. Beginning in 1980 through 1981, Jarvis began to take his Yamaha CS-15 to the club and play it over the DJ’s mix. Fellow DJ and Garage member Timmy Regisford heard him and invited him to collaborate on his new radio show on WBLS. The two began to hang out between shows to develop sounds they would play on air.

With Jarvis on his synths, Regisford began to use a reel-to-reel player to make cut-and-paste beats out of the drum record Mix Your Own Stars. Regisford recruited his neighbor, up-and-coming DJ Tony Humphries to handle the mix. The result was a string of tracks in the early ‘80s specifically intended for club play.

‘The Music Got Me’, their most successful collaboration, has a distinct house feel, though it was released well before the highly influential Chicago records from Mr. Fingers, Steve ‘Silk’ Hurley, and Marshall Jefferson ever made their way East.

Regisford and Humphries both cemented legendary reputations behind the decks and continue to DJ around the world, while Jarvis worked as a producer and session artist until he died in 2018.

4. Electro

Shannon, ‘Let the Music Play’

New York-based producers Arthur Baker, John Robie began to give dance heads a taste of the future in the early 80s with early electro singles like ‘Planet Rock’ by Afrika Bambaataa and the Soulsonic Force and ‘IOU’ by the UK band Freeez.

Producers Chris Barbosa and Mark Ligget took up the electro flame in 1983 and hired vocalist Shannon to take the fledgling sound into maturity. The result was Shannon’s breakout single ‘Let the Music Play’. The track hit the top spot on the Billboard Dance Chart, crossed over to #2 on the R&B/Hip Hop chart, and reached #8 on the Billboard Hot 100. The subsequent album would go on to sell over one million copies worldwide.

Armand Van Helden described ‘Let the Music Play’ as the “first strong vocals over electro.” Its syncopated, Caribbean-inflected beat featured a reverb-heavy, hard-gated Roland TR-808 drum machine. The bass line was played on a TR-909 with an unadjusted filter. The combination of these two would later become a signature instrumentation for the acid house movement. The track also features bass player Rusty Taylor, who was DJ Disciple’s neighbor in the Farragut Houses in Brooklyn when he was growing up.

5. Chicago House

Fingers Inc., ‘Mystery of Love’

Any attempt to sketch out the evolution of New York house music would be incomplete without Chicago house music. In many cases, Chicago house records made a splash among a dedicated but insular dance community where they were produced, but had huge impacts elsewhere in the world. Tracks like ‘Love Can’t Turn Around’ by Farley “Jackmaster” Funk, and ‘Jack Your Body’ by Steve “Silk” Hurley barely sold in Chicago, but they charted in the United Kingdom. English audiences took these records and ran with them. These singles may not have had the same commercial impact in New York, but they burned through Manhattan clubs.

In the late 80s, multi-instrumentalist Mr. Fingers, also known as Larry Heard, began to bring together vocalists Robert Owens and Ron Wilson to produce the first full-length house music album Another Side. Decadent and miles deep, the 1988 album alone provides an easy comeback to any listener who writes house off as simple or surface.

DJ Disciple credits a live mix featuring the LP’s track ‘Mystery of Love’ (along with some help from Adonis) with converting him into a dedicated house head at a party thrown by his friend DJ Jaz in 1988.

“It was an anonymous a capella laid to the groove of Fingers Inc.’s ‘Mystery of Love’ that got me open,” Disciple remembers. “DJ Jazzy Jerome blended the two together before I heard Robert Owens’ vocals, making me trainspot. These were the first two records that would lead me to vinyl whoreism. It was all Larry Heard’s fault. I was happy just being a gospel DJ, content with mixing Commission records over Run-DMC beats. But if Larry Heard pushed me to the edge it was Adonis that made me take the house music plunge with his atmospheric ‘No Way Back.’ The way my friends Louisa Harris, Kassim Hinds, Lian, Roche, and Sean moved to the house music Jaz was playing that night was like nothing I’d ever seen before.”

6. Hip House

The Jungle Brothers, ‘I’ll House You’

If Chicago invented house music and New York invented hip hop, then one can argue that 1988 marks the year in which their cross pollination began to bear commercial fruit. The Jungle Brothers’ debut album Welcome to the Jungle features iconic first-generation hip hop fused with jazz and house beats. The single ‘I’ll House You’, which was recorded a few months after the initial release and added to the album in subsequent pressings, exemplifies this crossover.

It all came together when the teenage JBs went into the studio after school and the sound engineer asked if they wanted to make a house record. He played them Todd Terry’s ‘Can You Party’ (released under the name Royal House), and they were hooked. They built the seminal track on top of Terry’s sample-heavy drum machine beat.

Terry, for his part, originally set out to get into hip hop. “When I first did house music I thought it was a joke,” Terry told us. “I didn’t take it seriously. I was just doing it because my friend said it was cool. I wasn’t getting any rap record deals. So I said you know what? I’ll just do a couple of these beats and see how it goes. That’s when I got my first record deal. I always liked to fuse James Brown into a house beat. It’s funky to me and I think that it has more longevity to it than just a plain kick and snare.”

Hip house had a brief moment in the sun in the late 80s and early 90s, with contributions from artists like Queen Latifah, Tyree, Fast Eddie, Rob Base and DJ E-Z Rock, along with accompanying UK hits from Beatmasters, MARRS, and Bomb the Bass.

New York house music reached maturity in the late 80s and early 90s. Shortly thereafter, nightclubs and dance music culture were attacked and pushed underground by the mayor’s office. Starting with the Happy Land Fire in 1990, Mayor David Dinkins created a club inspection task force to monitor nightlife safety. When Rudy Giuliani took his seat four years later, he turned Dinkins’ efforts up to eleven, introduced zero-tolerance policing, and initiated “quality of life improvements” that wreaked havoc with the New York house music community.

Luckily for house heads, the music had already migrated elsewhere in the US and across the Atlantic to the UK, Europe, and beyond. The English became the primary culture bearers of house music through the 90s and early 2000s until EDM reignited interest around the world. Only in recent years have more casual listeners been able to discover the roots of the music they dance to, thanks in part to the work of Lady Gaga, Beyonce, and Drake. Still, to true New York house heads, the scene never died.

The Beat, The Scene, The Sound: A DJ’s Journey Through the Rise, Fall, and Rebirth of House Music in New York City by DJ Disciple and Henry Kronk is published by Rowman & Littlefield