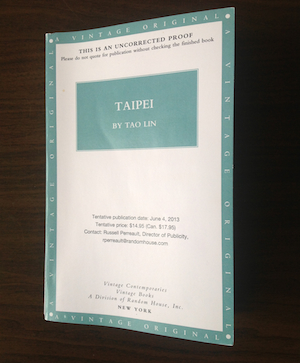

I was eating “Greek” yoghurt when my neighbour put her finger on the doorbell. She handed me a package that earlier I had heard her receive, with uncertain gratitude, after ignoring the postman myself, in fear of what he might be, both of us realising now, stood there, showing teeth, that the errant transaction was complete. I read the address with a neutral expression, seeing it was from New York, and – aware now of some growing anticipation – peeled the envelope open. I took out the book and turned it over in my hand, noticing this was not the cover I had been expecting, being instead an uncorrected proof of Tao Lin’s latest book, with a medium-to-large-sized image of the author amongst some trees on the back cover.

Taipei is the one, supposedly, as if any book could, or had the ability to be, when placed in the context of a larger chronology, one in which books make people “succeed” or “fail”, in which books make people do anything, egregious or useful, that will take Tao Lin to “the next level”, of something unspecified.

I opened it and read the first few lines; “cloudless-seeming”; “masklike”; “Paul had resigned to not speaking and was beginning to feel more like he was “moving through the universe” than “walking on a sidewalk.”” Again the use of “words” in quotations familiar to his other books, the zombielike, dolly-shot neutrality of his prose, I noticed, as if arriving at a decision, did not “make” me feel disappointed. I tried to finish the dessert, but kept thinking of those first few lines, spooning the strained yoghurt into my face.

Lin has notoriously cut into lines the sensibilities of critics and readers. Many want him to fail – they type as much in various comment sections across various blogs/journals, and by voting with their fingers on GoodReads – perhaps an unequal number to those that wish for him to succeed, and perhaps even more unequal a number to those that do not yet know of his existence. Perhaps they are envious of his ability to create whirlwinds, then guide them around the country in pursuit of his iPaths, or perhaps irritated by his refusal to create what they want in terms of whirlwinds. But, with this book, it seems, he cannot “fail”.

Appearing to place itself as one of the more accessible books in Lin’s oeuvre, as easily titled Macbook as Taipei (according to its author), Lin hands us, through the doorway, like a neighbour, his latest: a pseudo-semi-autobiographical (who knows) work, somewhere close to memoir, of around the last 29 years of his life (he is currently 29 years of age), with varied focus on his early years – in which a lucid, relatable, revealing description of his developing self-conscious disposition is given – up to, more specifically, the last two to three years, since publishing Shoplifting from American Apparel and Richard Yates, while subsequently ingesting consistent equations of normality-inducing helpers.

Charted in this book with almost mathematical precision (the language of which is often employed to comic effect) is Paul’s (Lin’s) book tour, his break-up with Michelle, his subsequent relationship and break-up with Laura, his two trips to Taiwan where his reversed-émigré parents now live, his marriage to Erin (writer Megan Boyle), changeable relationships with other artists/writers (including Jordan Castro, Noah Cicero, and others) and countless other interactions with other humans. Despite all of these events, some have already argued, citing too his previous work, either as a frustrated response to the lack of plot, or a lack of narrative direction, or a lack of whirlwind, or a lack of something else, that ‘nothing ever happens’. It merely seems as if, in the stream of his long yet staccato sentences, Lin has again stripped of this network of experiences the urge to create an arbitrary development of things beyond what is delivered in the minutiae of his observations.

At first, as reader, it is somewhat difficult to establish a rhythm, something I have noticed only once before (with Novahead by Steve Aylett) that, due to its density, once the understanding is reached, the style is extremely rewarding, in that it feels new, and different, and thrilling; that contained between a look between two characters is a series of interconnected universes behind the wobbly eyeballs of which we get not only a glimpse, but more of a 3D animation which he guides us through, like Richard Attenborough giving the tour near the beginning of Jurassic Park, and you, the cynical Jeff Goldblum. One sequence in particular, that produces almost digital, or computer-generated images, in the reader’s mind, elaborate animations that seem to actually “move”, provides a new way of looking:

“When he heard laughter, before he could think or feel anything, his heart would already be beating like he’d sprinted twenty yards. As the beating gradually normalized he’d think of how his heart, unlike him, was safely contained within blankets of skin, scaffolded by bone, held by muscles and arteries in its place, carefully off-center, as if to artfully assert itself as source and creator, having grown the chest around itself to hide inside and to muffle and absorb – and, later, after innovating the brain and face and limbs, to convert into productive behavior – its uncontrollable, indefensible, unexplainable, embarrassing squeezing of itself.”

This almost confrontational-feeling assertiveness in style is as if Lin is wilfully shaping his audience. Taipei reads as if narrated by a not-too-distant brain, written by, and for, no one in particular, but simply “is”. As if Schopenhauer’s assertion (oft cited by Lin), that one’s life should read like a book already written, to detach oneself from the pain, has manifested itself within Lin’s own life, the words spider through the pages as if somehow they have always been there.

Taipei does also, however, at times, read as if amended with heavy editing in post-production, where Lin has returned, after a third or fourth draft perhaps, to expand and elucidate certain motions and emotions (one that strangely leads to nowhere), until you realise that it is in these seemingly small, choppy expansions that Lin achieves his all-encompassing, expansive state of experience; that the experience of reading (living?) is in these details, and the sometimes obvious effort they have taken, little to do with the plot, that creates this air of uncertain, nightmarish awareness, of dread, of indeterminate “lost-ness” (“moving through the universe”) that, though you are grateful for his account, you are glad you were not there, before realising, of course, that you are there, narrating your own account, where all things are made transparent; people’s behaviour, their organs, their words, projected, as if onto a silk screen. This effect seems most perfectly realised in the final scene; one reminiscent of the entirety and floating of Enter the Void, after which Paul, surprisingly, comes to a concrete conclusion. As if Paul has died, he wonders out of his body by accident, then returns.

“…and was surprised when, looking at his feet stepping into black sandals, he heard himself say that he felt “grateful to be alive.””

Some other moments do, however, seem incongruous with the whole; they appear too plainly “nice”, a description of the sky, for example, which was pink, at one time, stands out of place, lost amongst the meticulous detail given to other areas. Many paragraphs/chapters start with a short description in this manner, perhaps as a placeholder, of the time and place, and the weather, as if remnants of an earlier draft, while “the end” appears as if an “end” has been enforced.

Familiar to some will be the occasional anecdote, one in particular which appears near the beginning of the book, to do with two rival house parties, members of which are encouraged to leave one to attend another, that caused a rift between several friends (and a couple of Facebook un-friendings and Twitter un-followings). Lin seems to be addressing these quite tiresome events as a way of explanation for his behaviour at the time, at all times, fitting them in to others, his school history, for example, of becoming overly self-aware, to a degree almost debilitating, that are authentic, relatable, and insightful, even profoundly endearing, becoming also a truthful account of what it is to be a child, not meeting another’s expectations of one’s self, being trapped by that perceived set of expectations, and not even meeting one’s own, more often than not, bringing Paul to certain realisations about the people around him:

“Laura ordered a margarita, then sometimes turned her head ninety degrees, to her right, to stare outside – at the sidewalk, or the quiet street – with a self-consciously worried expression, seeming disoriented and shy in a distinct, uncommon manner indicating to Paul an underlying sensation of “total yet failing” (as opposed to most people’s “partial and successful”) effort, in terms of the social interaction but, it would often affectingly seem, also generally, in terms of existing. Paul had gradually recognized this demeanor, the past few years, as characteristic, to some degree, of every person, maybe since middle school, with whom he’d been able to form a friendship or enter a relationship (or, it sometimes seemed, earnestly interact and not feel alienated or insane).”

But it is within this wider context, dealing with ideas of eternal return, “making it”, accomplishment, life/death, and other indeterminate values, that Lin places his reader. At one stage, he points out, after some initial confusion as to what their current objective is, walking along the street in the wrong direction, ““We just actually forgot out purpose, then regained it,” said Paul grinning. “We still kept moving at the same speed, when we had no goal.””

He also addresses, directly, the question of “drugs” and “drug problems,” within a discussion of the constant e-mail correspondence with his worried mother, who continually insists on him not doing drugs, and also in conversations between him and his companions, sometimes whilst on LSD and mushrooms.

“They began talking about a Lil Wayne documentary that focused on Lil Wayne’s “drug problem,” which Lil Wayne denied. Paul felt it was bleak and depressing that the filmmakers superimposed their views onto Lil Wayne. Calvin seemed to agree with the documentary. Paul tried, with Erin, who agreed with him, he felt, to convey (mostly by slowly saying variations of “no” and “I can’t think right now”) that there was no such thing as a “drug problem” or even “drugs” – unless anything anyone ever did or thought or felt was considered both a drug and a problem – in that each thought or feeling or object, seen or touched or absorbed or remembered, at whatever coordinate of space-time, would have a unique effect, which each ever-changing person, at each moment of their life, could view as a problem, or not, for themselves.”

He touches on how all areas of experience/action/thought are filtered through a need and effect of altering consciousness; be they forming friendships, looking at a tree, or eating a greasy muffin, it all affects cognition in some form, so to separate one need/effect from another is to miss the point.

Later, in an oddly interview-like conversation with Erin, they address these concepts again, also in terms of relationships, but it never feels gratuitous, or edifying. Paul and Erin feel, after a time, that their serotonin levels are “depleted”, hinting, though with permanent neutrality, not at the eventual neurotoxicity of extended MDMA consumption, but instead focussing on its effect in their lives, that, slotted into the cycle, this “depleted” may perhaps refer to their brains in general.

Paul’s relationship with Erin goes through somewhat of a progression, comparable even to a dab of MDMA in itself, where at first they are both as if synchronised, fascinated/obsessed with one another, later they become distant, and out of phase, and, after their Vegas wedding, their connection becomes increasingly strained, to the point where Paul imagines Erin to be crying in bathrooms alone, and uncertain whether the sounds he hears are real, or just an effect of how his brain thinks he/she must be feeling. They even openly admit to each other that their marriage is likely to last only five weeks/months/years at best.

He notices her behaving differently amongst other people when he is not there. She is freer, livelier, until he comes back into vision, and she becomes sullen. They begin to exhibit behaviour that they abhorred in discussions of previous relationships, checking up on each other, eating unhealthy food to “console” oneself, or openly shouting at each other, for example, each behaviour beginning to grate and find routine in their marriage, out of what source, as in “reality”, it is as unknown to the participants, as the readers; shifts in mood appear like thoughts, from a corner unseen. Later, back in the US, they have their first “drug fight”, and it feels like the end. But somehow, because of a certain aforementioned detachment, and a series of amusing drug pick-ups from a man named Peanut, it can often be grimly hilarious.

After a while in Taipei – the place that becomes a familiar yet alien landscape, full of neon glow and Filet-o-Fish – Paul’s will to continue their current, shared direction starts to dissipate. Erin fears she will become like many others before her, that Paul has spent months at a time with; people can be close to him, physically, until the connection is suddenly cut, by circumstance or by force, meaning they may not see each other again.

Where at first their interaction is earnest, it seems earnest interactions between them, after that, become increasingly hard to come by, as if they must hide from each other what they already know. When someone makes a comment about something that, in another book, could be considered cloying or pretentious, it is playfully mocked here (a point that some detractors attack Lin for), and amusing, impelling on the reader, Paul’s characteristic grin.

But that everything seems filtered through a joint venture of taking MDMA, LSD, Xanax, Ritalin, Adderall, eventually Heroin, etc. it brings to the fore their inherent alienation (a popular word), that even in delightful shared experiences, Paul must remain completely separate, and victim of his continually developing self-consciousness.

Earnestness even seems, sometimes, to be consciously avoided, or, when accidentally chanced upon, it is embarrassedly ignored, a symptom of the self-conscious mind:

““Look, beautiful,” said Paul earnestly about the hundreds of red lights on the backs of cars, passing beneath the walkway, drifting idly away like rubies in some massive and ongoing theft.

“Whoa,” said Erin. “Pretty.”

“Life sometimes offers beautiful images,” said Paul in a voice like he was in fifth grade reading a textbook aloud.

“But they’re fleeting. And you can’t do anything with them–”

“Yeah,” said Paul grinning.

“–except look at them,” said Erin.”

“Maybe we should get drunk,” said Paul, and they entered the casino at the end of the walkway, and Erin went to the bathroom.”

Other times earnestness is mistaken for irony, an honest question about listening to a band (Rilo Kiley) is taken as a joke by one of his friends, while Paul replies, “I wouldn’t joke about something like that.” Then says, “he wouldn’t pretend he liked something, or make fun of liking something, or like something “ironically.”” It seems that these misunderstandings are out of his control, returning us to that set of expectations again, and in so doing, gives a sense that, in this book, everything and its opposite is accounted for.

When not distracted by making Macbook films about Taiwan’s First McDonald’s (and how, in Taiwan, McDonald’s have imitated the white picket fence image of the American front yard), or, when not distracted by riffing on the blandly unspecific smiling faces on billboards surrounding them, this breaking apart becomes all the more awkward in close proximity to Paul’s sweet-natured, often childlike parents (jarringly, it seems, similar to my own). That their raised voices can be heard through the shared walls of his parents’ apartment, small gestures become crises and, after the initial discovery of their connection, its appeal recedes until Paul is again “hovering low with bent elbows, feeling both insane and, in the private room behind the one-way mirror of his exaggeratedly happy expression, bored and alone”.

But this “bored and alone”, with Paul, seems as equally apparent when amongst people as when actually alone in his “default lifestyle”, lying around on his bed not knowing what to do for the months leading up to his book tour and avoiding all other social obligations, so that when he does actually happen to move through crowds at parties, trying to be unnoticed, or unseen, and allowed to just be, waiting, patiently, for it to end, he has accepted, both ways, that one cannot leave until the “party” is over. And, it seems, in that ending, he doesn’t want to.

In interviews, Lin has since stated he would rather write shorter things, short enough to memorise, perhaps his next title being I Don’t Want to Sleep but I Don’t Know What I’m Waiting For, mentioned here. Either way, whether he writes another novel, or book of poetry, or not, it is genuinely exciting that Lin is still early in his career. Here he has documented, with as-seemingly-close-to-objective insight as possible, this constellation of people, like gases and matter, coming together and exhausting their fuel, and whatever happens, whether the connections survive, it all seems the same, and not limited to one outcome.

Later, I was spooning more “Greek” yoghurt, looking at it thinking there is no way this can “fail”. And the first words of Taipei were still there; “masklike; “cloudless-seeming”; “more like he was “moving through the universe” than “walking on a sidewalk.”” when someone put their finger on the doorbell, and I went to open it, grinning. The postman handed me the package and, with gratitude, I opened it while he waited.

“Taipei?” said the postman, pointing.

“Yes.”

But the cover had changed. TAIPEI TAO LIN: the words all glittery. Then, turning it, I saw the author photograph was gone. For a second, eyes unfocussed, holding the book in my hands, I realised, glumly, that I was the uncorrected proof.

Taipei is published in June by Vintage Books

Follow @theQuietusBooks on Twitter for more