Imagine telling somebody that they were inevitably going to commit suicide. That it was going to happen. That there was no other option. It would be nothing short of abusive.

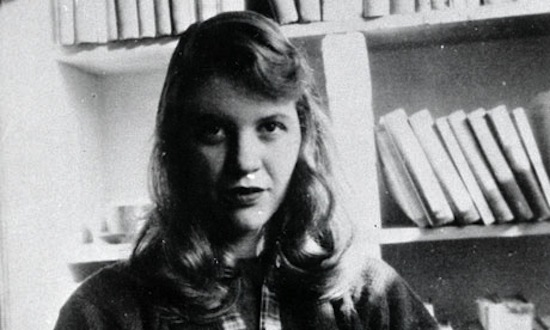

In the recent media coverage surrounding the 50th anniversary of Sylvia Plath’s suicide, on February 11 1963, when she left the manuscript of the volume of poetry that would become Ariel, I have noticed the recurrence of two refrains about Sylvia Plath: one is that her work should be read for its own sake, and not as a key to her biography (or as a way to understand her suicide), and the other is that she should not be overshadowed by her husband – the oft-villified Ted Hughes. These arguments are not new, yet they keep having to be made, seemingly symptomatic of the confessional nature of Plath’s work. Her writing undeniably included details from her life, yet it simultaneously fictionalised and poeticised them, making it impossible (let alone silly) to try and definitively interpret her life through her work.

But both her work and the nature of her death did make people want to understand. Death, after all, is the great unknown – it seems only natural to want to know what happens next, or – perhaps more profoundly – what it means to die. The reasons why someone would take their own life also have a peculiar kind of urgency: why would they do it? Surely this is why Al Alvarez, Plath’s friend and one of the best poetry critics of the twentieth century, wrote his study of suicide, The Savage God, after her death. Indeed, I can’t imagine how anyone would attempt to mourn the suicide of a loved one without trying to assign reason to it.

Like many people – from Girls creator Lena Dunham, to the theorist and academic Jacqueline Rose – who have been talking about Plath lately, I have ironically introduced my argument with exactly that topic and occasion (the anniversary of her suicide) from which people argue her work should be separated. I want to point out something about the reception of Plath, not since her death but since Ariel was published, that I think is more pernicious than what has lead to the two refrains above: the way that her work has been read, often unconsciously, as if she were always going to kill herself. To move Sylvia Plath and her work in the way that it deserves, into the twenty first century, and to hand her over in the best possible way to a new generation of readers, this narrative must be exorcised.

The initial construction of this narrative came through Hughes’ alteration of the order in which Plath had left the Ariel poems: though her version of the manuscript finished in a sequence known as the bee poems, Hughes changed the final three poems of Ariel to ‘Contusion’, ‘Edge’ and ‘Words’. That this changed the entire feeling of the volume to a more gloomy and fateful ending was forcefully argued by Marjorie Perloff in 1984, in an article in American Poetry Review. According to Perloff, Hughes’ editing both robbed the poetry of a cycle of positive rebirth valuable to feminism and implied ‘that Plath’s suicide was inevitable (‘I have done it again’), that it was brought on, not by her actual circumstances, but by her essential and seemingly incurable schizophrenia’. Frieda Hughes, Ted and Sylvia’s daughter, implicitly responded to Hughes’ editing in an introduction to Ariel: The Restored Edition, published in 2004, arguing for a refocus on her mother’s poetry (she also stated that Hughes had been its ‘victim’).

An article by Hughes titled ‘Notes on the Chronological Order of Sylvia Plath’s Poems’, published in Tri-Quarterly in 1966, and later reprinted in a collection edited by Charles Newman, states that ‘Contusion’, ‘Edge’ and ‘Words’ were the last poems Plath wrote in her life: he therefore rearranged the poetry to recreate Plath’s life, and many key critics have repeated the knowledge of this in their interpretation of these poems. For example, in an article titled ‘Plath and Lowell’s Last Words’, Steven Gould Axelrod wrote: ‘In Sylvia Plath’s last poems, written in the week of her suicide, poems like ‘Contusion’, ‘Edge’ and ‘Words’, we find the Confessional journey gone beyond the point of no return. Plath has become so extreme that she falls off the edge’. Here Plath has become her writing, doomed to fall into the unknown abyss. In the “analysis” of ‘Words’ in her biography of Plath, Bitter Fame, Anne Stevenson wrote ‘All that will be left of the poet will be disembodied words while “From the bottom of the pool, fixed stars | Govern a life”’. Thus directly narrating Plath’s suicide via ‘Words’, Stevenson also added words like ‘bleed’ and ‘horror’ to her description, none of which are in Plath’s remarkably controlled poem, and the poet literally becomes her words. Simple elisions and elaborations like these are how Plath’s work came to be inflated not just with her life: her death was wrought into the meaning of her work.

As well as with the editing of Ariel, the attachment of Plath’s work to her death was augmented through three crucial things said by Alvarez, Hughes, and Robert Lowell, at the time one of the most influential poets in the world, and a former teacher of Plath’s. In a 1965 review of Ariel, titled ‘Poetry in Extremis’, Alvarez wrote that since Plath had spent the last few weeks of her life writing about death, when hers came it was ‘in a way, inevitable, even justified, like some final unwritten poem’. Then in the introduction to the American edition of Ariel Lowell wrote that ‘in these poems’ Plath was not a human but a tragic heroine, a Phaedre or Elektra, playing a game of Russian Roulette. Lowell completed his picture of Plath as governed by fate and dicing with death with a memory of her at his Boston University poetry class (which she attended along with Anne Sexton): ‘her art’s immorality is life’s disintegration’, he wrote, and ‘I sensed her abashment and distinction, and never guessed her later appalling and triumphant fulfilment’. Although these remarks have been treated to some scepticism, it is not hard to see how Plath’s poetry encouraged them: Plath wrote, in ‘Edge’, ‘The illusion of a Greek necessity | Flows in the scrolls of her toga’, and Lowell’s image of a classical tragic heroine seems a response to this – though, of course, Lowell’s quote is taken from one of the three final poems in Hughes’ edit of the book. Lowell’s metaphor, ‘Russian Roulette’, became the title of a titillating review of Ariel in Newsweek in 1966, which described a book ‘so full of blood and brain that it seems to burst on the page and splatter the reader with the plasma of life’. Time magazine wrote that the Ariel poem ‘Daddy’ was ‘merely the first jet of flame from a literary dragon who in the last months of her life breathed a burning river of bale across the literary landscape.’ In all of these images, Plath was already doomed and deathly when she was writing her poetry (for Lowell, as early as three years before her death).

It’s not hard to see how this backwards-projected fatality might affect people’s reading of Plath’s poetry – there is also a suggestion that she wrote herself to death. Completing the picture, in his introduction to Sylvia Plath: Collected Poems, published in 1981, Ted Hughes articulated the interest of Plath’s early poetry, first published here, as being that ‘even at their weakest they help chart the full acceleration towards her final take-off’. By doing so he moulded all the interest of Plaths’ poetry to the last work of her life. Through the ideas of Plath’s ‘final unwritten poem’, her ‘triumphant fulfilment’ (in an introduction to Ariel with Hughes’ ending), and her poetry’s ‘final take-off’, a myth was built up in which Plath’s true poetic voice emerged only as she hurtled closer to suicide.

Just how far this narrative has been transmitted and augmented through the years is perhaps most obvious in the 2003 biopic Sylvia, starring Gwyneth Paltrow, which begins not with Plath’s birth or even her childhood, but when she met Hughes at Cambridge. (There thus appears to be no Plath without Hughes.) Throughout the film there are images forecasting Sylvia’s death; it begins in fact with Paltrow lying down with her eyes shut. Presumably she is dreaming, since the voiceover is a famous quote from Plath’s novel The Bell Jar about a dream of a tree whose branches represent the different and competing options for her future life – but there is something corpse-like about her. Within a mere fifteen minutes, too, she mentions explicitly her first suicide attempt. The immediate scene after Ted and Sylvia’s first big argument in the film is Sylvia lying, again cadaver-esque, in the bath. Most of the scenes of her writing poetry are as a response to meeting, or arguing with Hughes, which may be what lead one Daily Mail reviewer of the film to conclude, ‘she found it hard to write unless she was unhappy’. The film also makes the lines ‘black marauder | one day I’ll have my death of him’, from Plath’s extraordinary poem ‘Pursuit’, literally about Hughes: in the actual poem, in which the pursuer is said to be a panther, these lines are separate, in the reverse order, and two stanzas apart. Two juxtaposed scenes where Sylvia and Ted are teaching, separately, use similarly dramatic and fateful quotes: ‘The American has got to destroy’, says Sylvia, and then as she walks into Ted’s lecture he is reading lines from Yeats’ The Sorrow of Love: ‘and then you came with those red mournful lips, |and with you came the whole of the world’s tears’.

To Alvarez’s credit, at a symposium on Plath in Oxford in 2007, he reinstated the view he put forward in The Savage God – that she had not meant to kill herself, but had intended to be saved. This does not seem unlikely, given that she had already been saved once. All interpretations of Plath that have interpreted her as having committed to the act of suicide when she was writing her poetry are morally unjustifiable. Nobody’s suicide can be an inevitability. Forecasting Plath’s death through her work is an abusive and reductive way to read her, mapping the trajectory of her death on to a life still being lived.

For me, the things that made Plath one of the most important writers of the twentieth century were her extraordinary innovations in poetic form, her ability to shift between metaphors to create myriad meaning and, of course, the way she wrote about gender and sex. And what made the confessional aspect of her work important was not that she breathed fire onto the literary landscape, and absolutely not what clues she gave us to her life, but that by fictionalising her life she questioned necessity. The force of that most famous poem ‘Daddy’ does not come from giving in to the patriarchy she portrays, but from a refusal of it: ‘you do not do, you do not do | Any more, black shoe’. The bee poems, which every Plath reader must read, construct a different patriarchy through which there is survival and, as Perloff insisted, the possibility of rebirth:

Succeed in banking their fires

To enter another year?

What will they taste of, the Christmas roses?

The bees are flying. They taste the spring.

I hope that in the next fifty years Plath will be freed from the fatality imposed upon her work, and that it will be read for all its life and complexity.

The works of Sylvia Plath continue to be published by Faber & Faber, including a newly-edited volume of her poetry: Sylvia Plath: Poems, Chosen by Carol Ann Duffy

Follow @theQuietusBooks on Twitter for more