“They say when you’re dying, hunger is the first thing to go.”

By the time Roberta, on the penultimate page of the invigorating debut novel by Manchester-based author Lara Williams, has come to reflect on that unsettling aphorism, the attentive and sympathetic reader will no doubt be tempted to quietly punch the air. Or, in keeping with the halting modesty (and, at times, pained self-loathing) with which her narrator recounts her troubled – and troubling – navigation of the decade between starting university and the beginning of “the deeply private communion” from which the book takes its title, perhaps just nod. Eagerly, quietly. Hungrily. Roberta, as evidenced by a dazzling final set-piece, is very much alive.

Supper Club, fittingly, is a sensory feast: nourishing, and darkly so. Its measure, perhaps, is the shining sliver of hope sewn into the novel’s immaculate closing line. It gives little away, certainly not to readers hooked by Williams’ tender debut collection of short stories Treats, to reveal here that Roberta’s story comes to a conclusion as compassionate as it is satisfying.

That story, told in chapters that alternate between those two distinct timelines, eschews much of the stark formality of Williams’ short form. Whereas Treats revelled in its forensic peeling of the unfathomable horrors of the humdrum (work, relationships, sexual malaise – “Do you want me to be the male penguin or the female one?” asks the baffled but kind-hearted narrator of her partner in ‘Penguins’, one of Treats’ many comic highlights), Supper Club prioritises story over styling. Its mode is notably more conventional and accessible. (It is not just Williams’ switch from the much-missed Scottish indie Freight Books to Hamish Hamilton that will aid the expansion of her readership.) Delivered in an intimate first-person, it invites the reader to invest in a life lived both meekly and then, as a late twenties ennui threatens to overwhelm Roberta, fully and dangerously.

Those of us still recovering from the bleak disappointment of university life (“These were not the sort of people I’d left home for”), will cheer Roberta’s re-claiming of self that follows as a result of stumbling career progress, making new friends (the talismanic Stevie, whose presence both empowers and threatens Roberta), and the devilish act of creativity and kinship that is Supper Club. While the re-connection with both a friend and a lover from the novel’s earlier strand might appear something of a narrative stretch, the latter, certainly, allows for a hefty serving of something approaching revenge – though this is one dish, years in the planning, served chilled to the bone. As the abusive Arnold (a priggish egoist, whose gutless cruelty recalls the monstrous Edwyn in Gwendoline Riley’s First Love) sits across from her at dinner, in cool judgement, Roberta finally stops his breath: “You must be really embarrassed. You must be really embarrassed you just explained feminism to me.”

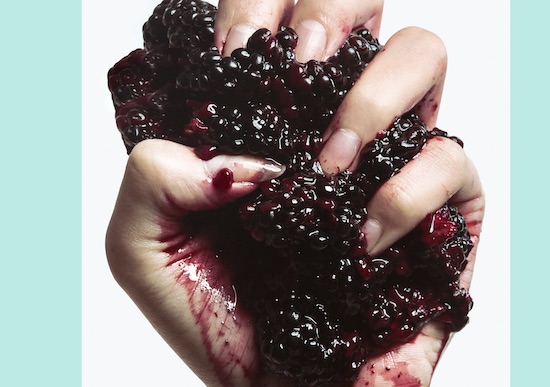

But it is the Supper Club itself, her “marvellous feminist sisterhood”, that most vividly defines Roberta’s courage and evolution. A secret feasting society, its membership at any one time is drawn largely from women rebounding from the awfulness of the men who, in various forms, are draining them of their energy, dignity, life. Women abused by the men they serve, women betrayed by their husbands, women – in the case of Monica – a mere abortion away from a life with the dreadful Thoman, whose solicitor sister and brother-in-law parade their BMW shopping and children (“toothy and flame-haired… with large demonic grins") with sinister ease.

Held in increasingly risky locations, from abandoned university buildings to a branch of Selfridges after closing, Supper Club becomes a wild rite, a group exercise in self-expression and unthinking abandon. The menu itself becomes as meaningful as the act: “We followed with bouillabaisse. Soup seemed the kind of meal women feel they should serve, rather than doing so out of any sense of appetite or desire.”

Alongside mouth-watering cataloguing of courses and accompaniments, Williams prefaces many chapters with detailed descriptions of how to cook a particular dish: soufflé; sourdough; puttanesca. Several pages long, they reinvent the notion of ‘recipe’, becoming a sensual instruction manual of not simply how to prepare food, but of what deep delight awaits those who take the trouble to do so.

In 2019, with the buying and preparing of food a basic human right increasingly denied to many, what shame should we reserve for the oft-brayed “Oh, I can’t cook, me”? Here is a book that both celebrates and politicises food with a raucous glee. And while Williams’ wry understatement of the perils of the soufflé is deadly relatable (“It has a reputation for going wrong”) it later gains a sweet and unexpected poignancy in her summation of – of all things – hunter’s stew.)

Elsewhere, Williams’ eye for detail is as keen as ever: the low level warring within relationships; an acutely observed, and continuing, taste for body horror (“…I took enormous joy in prying the large clot out of my nostril…”); the strangle hold of urban living. As Roberta stumbles alone through her first term, “[her] heart wound tentacles around the city, clutching blindly in the dark.” That kind of flinty poetry punctuates Williams’ developing voice: easy and expressive, it benefits from characterisation rich enough to give voice to the narrator’s deadpan observations and a clear-sightedness that deftly swerves the perils of maudlin self-pity.

Supper Club is more than just a rousing celebration of the female self, and of the sharing and community that more often than not is proven to be exclusively female. It blooms as a deeply moving portrait of how the rickety bridge from youth to (young) adulthood can be crossed if only we dare to embrace our fuck-ups and give the finger to the deep-rooted norms that question our suspicion that, actually, stomping on society’s throat is so much better for us than tip-toeing around its grabbing hands. If, like Roberta, you ever wanted to walk up to that friend who likes The Neon Demon and say to them “What is wrong with you?” (and why on earth wouldn’t you?), Supper Club awaits your membership application.

Supper Club by Lara Williams is published by Hamish Hamilton