Back in the mid-sixties, African and Eastern-style clothing was still relatively rare in New York, even in the East Village as it was then known. A light-skinned Black man, carrying a shopping bag and wearing a glittering tunic under his jacket, was bound to attract some attention on Second Avenue before noon, especially with his greased-down hair tied around with a star-spangled bandanna. He led the way up some stairs and into a room ablaze with light. The light came from inside a huge rubber ball suspended from the ceiling, and the room was filled with musicians and instruments of every description. Marshall Allen had been out to buy food for the occupants of 48 East Third Street, who included in their number the legendary pianist, poet and philosopher known as Sun Ra and several members of his Solar Arkestra. Another day at the Sun Studio was just beginning.

The night before, the musicians had rehearsed for four or five hours, something they did every night without much promise of remuneration in the foreseeable future. Sometimes they would play in a coffee-shop across the river in Newark, occasionally they might have a gig in the Village. Where they were concerned, however, Sun Ra, a thick-set man in his fifties with a paunchy face and hairline moustache, was the heaviest guru around. For Sun Ra himself, dressed in equally glittering attire and with a ten-pointed star shining out of the turban he wore on his head, their continuing presence was proof of the superiority of his music, despite the limited audience it enjoyed at the time.

Since those days, Sun Ra and the Arkestra have toured Europe and America and even visited Egypt. In Germany, they heard local bands come out playing solos taken almost note for note from some of their earlier recordings. In Cairo, the Minister of Culture arranged for a performance by the Egyptian Ballet to be cancelled so that the Arkestra could play. At one point, the thousand-strong audience leapt spontaneously to its feet to join the Arkestra in their chant; ‘Space is the Place’. The musicians took their cassette recorders to the pyramids and into the tombs and played their music there.

For a while, Sun Ra was Artist-in-Residence on the University of California campus at Berkeley. The Arkestra itself has moved to Philadelphia, but some things never change at the Sun Studio. Then, as now, it was not uncommon for Sun Ra’s apprentices to sit up half the night waiting patiently for the master to prepare an arrangement. Nearly all his writing is done at rehearsals, like Duke Ellington with the particular capacities of the individual in mind. ‘I write according to the day, the minute, and what’s going on in the cosmos,’ he says. ‘And actually each one of my numbers is just like a news item, only it’s like a cosmic newspaper.’

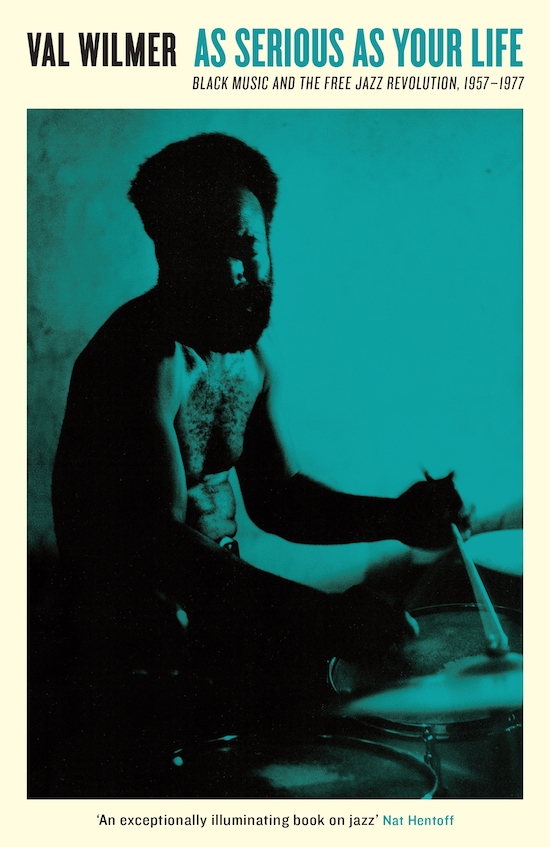

Val Wilmer author portrait

Sun Ra’s music had already been a driving force for ten years when he and the Arkestra moved to New York in 1961. Even before they left their original base in Chicago, their devotees would ask those who had heard them play on consecutive nights, ‘Has the band caught up with Sun Ra yet?’ His innovations, not to mention his espousal of the idea of intergalactic travel and its implications for the human race, have always been in advance of the contemporary attitude, yet it has been suggested by one writer that he ‘tied in’ with New York’s growing free-form movement on his arrival. The truth of it was that he and his musical spacemen were already there. ‘If you’re going to talk about “avant-garde”,’ said drummer Clifford Jarvis, ‘Sun Ra is the first in that particular music.’ ‘

Musically, Sun Ra is one of the unacknowledged legislators of the world.’ Roger Blank, another drummer who played and recorded with him, paraphrased Shelley in an attempt to describe his influence. Saxophonist Marion Brown, who has studied and taught extensively, is convinced that Sun Ra is greater than Stravinsky or Bartok, ‘And by my standards and by the standards I’ve acquired in getting my traditional education, I would say he is more creative than Cage or Stockhausen.’

On a record made before an audience in Cairo, Egypt, in 1971, Sun Ra was asked to define ‘progressive music’. ‘It means keeping ahead of the time,’ he said. ‘It’s supposed to stimulate people to think of themselves as modern freemen.’

Sun Ra has become conspicuous for his colourful attire, dressing in a style seemingly derived from somewhere midway between Africa and the realms of science fiction. It has been years, in fact, since he has allowed anyone to see him in Western dress (although there is a film in existence made at a party in the ’fifties where the guests stood around, drinks in hand, asking each other, ‘Have you heard the New Music – this new jazz?’ and the answer was provided by Sun Ra, conducting the Arkestra, all of whom were dressed in white tuxedos). His musical explorations are invariably related to journeys into Infinity beyond the Universe itself. ‘The Heliocentric World of Sun Ra’, ‘Lights on a Satellite’, ‘The Others in their World’, are the kind of titles he gives his compositions.

But these were idiosyncrasies. Sun Ra, who adopted the name of the Egyptian sun god and has always been deliberately mysterious about his origins, was ahead of the times in other ways. In Egypt, the Inspector of Antiquities told one of the musicians that he had never met anyone who could support the tremendous wisdom the name traditionally implied. Sun Ra has gone a long way towards doing so. He was the first artist to speak of spiritual matters and the need for personal discipline amongst musicians. Anyone who wanted to play with him had to accept a severe personal regimen – at least while they were in his company. Some of his shorter pieces even carry the titles of various numbered ‘Disciplines’.

‘Sun Ra runs his band like an army,’ a young saxophonist related from painful first-hand experience. ‘When he says, “Stand up!” they stand up. When he says, “Sit down!” they sit down.’ He even has one of their number stand guard at the door all night.

‘It’s like anything else,’ says Sun Ra. ‘When the Army wants to build men they isolate them. It’s just the case that these are musicians, but you might say they’re marines. They have to know everything. In their case, knowing everything means touching on all places of music. Of course they won’t get as much chance to play as other musicians, but on the other hand, they’re getting more chance to play.’

There is a certain anonymity about the players he chooses, however interesting or exciting their actual solos can be. At times it seems that Sun Ra’s influence is so strong that the musicians express him rather than themselves. In their kind of cold detachment, the musicians, though mature, appear in a student role. Implicit in Sun Ra’s statement, though, was the need he feels for the suppression of ego in those young players who flock to him full of hope, some of whom he sees having only ulterior motives. ‘They are selfish. They want to play to satisfy their ego and so that someone can applaud them. They refuse to throw their energy into a pool with someone who could be the link to do something with it.’

At the same time, Sun Ra, the visionary and catalyst, knows that his school provides an opportunity for really playing – no shucking, no jiving – that is without equal. Clifford Jarvis saw many young men crumble in the face of Sun Ra’s wisdom and demands. ‘He can build your hopes up and tear you down at the same time,’ he said. ‘A lot of guys wig out, you know. Some of them can’t stand to be that sincere. They don’t have any foundation to be that staid and stable with what Sun Ra has to offer.’

Sun Ra believes that discipline is the foundation of all freedom. He sees this reflected in nature and the universe itself, but just as no two organisms created by nature are alike, no two people are alike. He thrives off the notion of the individual’s ‘duality’. He says: ‘You can’t have harmony and you can’t even have real music unless you have two or more sounds. And you have to have two or more people to have harmony.’ Each individual, he believes, is music himself, and if he is unable to express this feeling, he must have his ‘spirit companion’ – i.e., the musician – to do it for him. To him, ‘the people are the instrument.’

Val Wilmer, As Serious As You Life: Black Music and the Free Jazz Revolution, 1957–1977, is available now from Profile Books