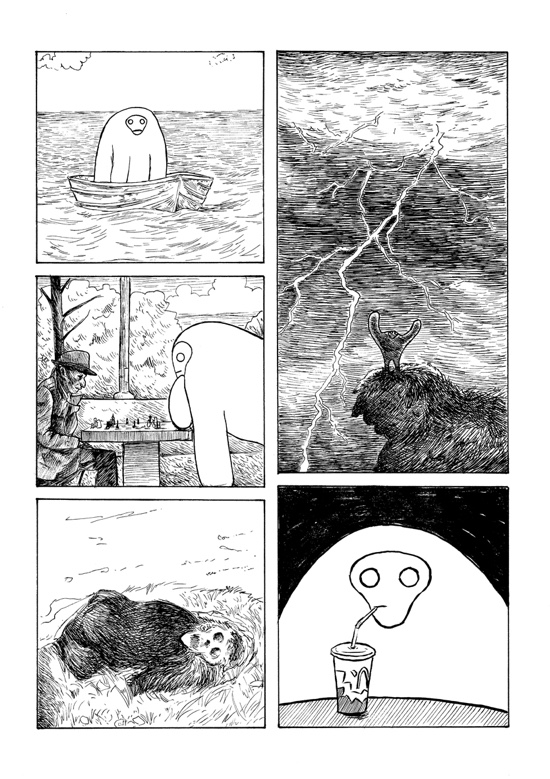

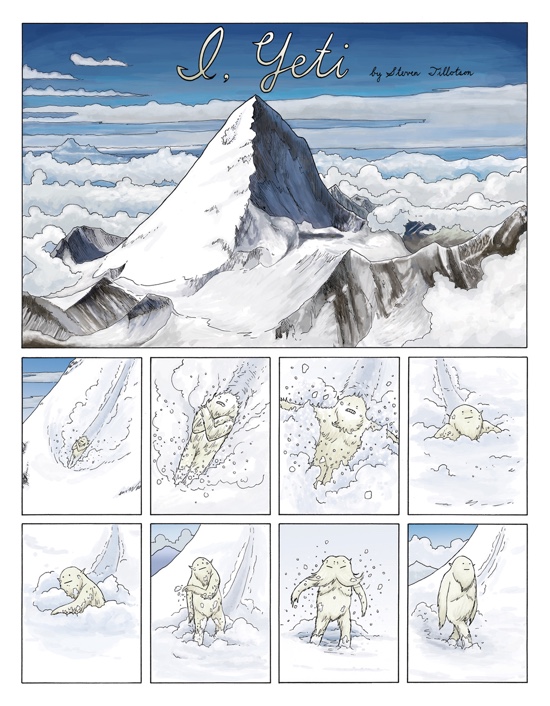

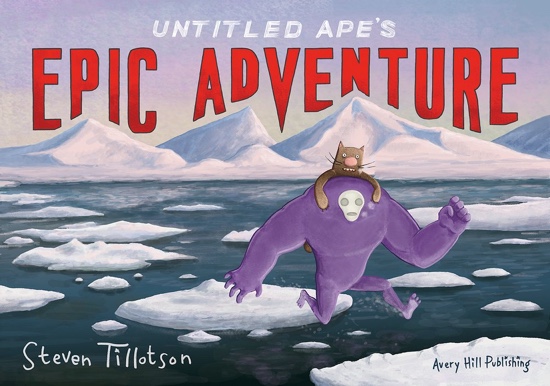

Steven “Steve”; “Banal Pig” Tillotson draws comics. You might have seen some of them. If like me you struggle to keep up with the infinite small press scene (and I care a lot and write about it a bit, although to be fair I’m also quite lazy) you’re most likely to have seen his Yeti comic in the published runners up of the Observer/Cape/Comica Short Graphic Story Competition in 2012. Or if your toes are a little further into the graphic narrative creative pool, you’re likely to have seen Banal Pig anthologies and most recently the feature length Untitled Ape’s Epic Adventure put out by Avery Hill last year and reviewed here.

His work plays with genre and realism in a satisfyingly leftfield way; his characters are deadpan, cynical cogs in the wheels of a surreal and ridiculous universe. So of course they are compulsory reading for contemporary denizens of reality. Visually, Tillotson’s current work is a masterful interplay of detail and simplicity that, like his writing, has developed through years of dedicated practice in the margins of day-to-day life. Less overtly grim than much of his earlier comic work (which has to be stringently labelled as not for kids, and believe me it is not) UAEA is a smart and bittersweet dystopian romp through several levels of what might loosely be recognised as Hell, Heaven and Earth.

Like most of us creatively inclined people, he has had to struggle to keep an upward trajectory against mundane obstacles such as the nonsensical value systems of art education and industry; the artist’s eternal instinct to begin new projects; the necessity of earning a living and other such distracting parts of life. But this is a struggle I would say he is definitely winning, a testament to the value of persevering with artistic practice, wherever it eventually takes us. I’ll let him introduce himself more concisely in his own words.

To start things off efficiently, Steven, what would it say in the first paragraph of your Wikipedia entry? If you were to have one written about you. You know, the section at the top?

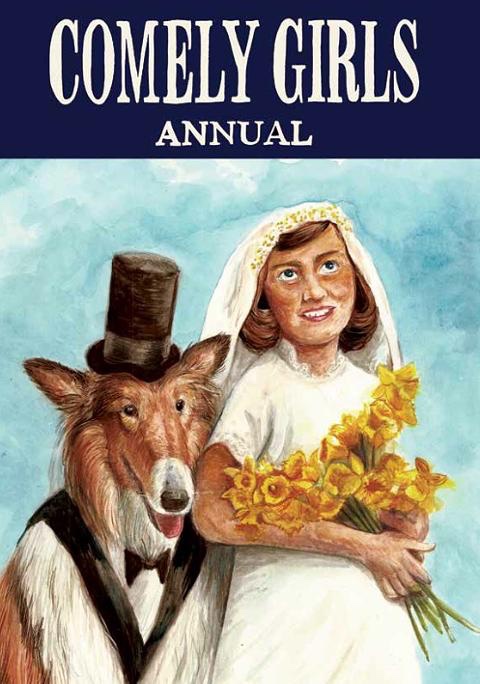

Steve Tillotson: My Wikipedia entry would be something along the lines of: Steven "Steve" Tillotson (1979 – present) is a comic creator, artist and illustrator from Bradford, UK. He is best known for his graphic novel Untitled Ape’s Epic Adventure published by Avery Hill Publishing in Nov 2016, and his darkly humorous self-published comics under the Banal Pig imprint from 2005-present, including Banal Comics #1-4, Christopher Wren In Search Of Excitement, Ethel Sparrowhawk’s Terrible Hangover and Chris Sandwich. His work also includes the Manly Boys and Comely Girls Annuals, produced with long-term collaborator Gareth Brookes. In 2003 he received an MA in Printmaking from the Royal College of Art, London.

Tillotson came back to comics and illustration after training in a more fine art direction; the low brow middle ground between ‘Art’ and ‘Design’ was and still is a growing territory where really the most fun work happens.

Who were your creative heroes growing up, and who are they now?

ST: My favourite comic growing up was Buster, and within that my favourite artist was Tom Paterson – his artwork was always the most dense and crazy, but I’d read all the humour comics I could get my hands on, like the Beano, Dandy, Whizzer And Chips, etc.

However, I’d grown out of comics long before art school (and didn’t really go in for superheroes), but I saw the work of Daniel Clowes and it really struck a chord with me – I’d not really thought about making my own comics seriously before that. Chris Ware’s books also help cement a passion for the art of comics that inspired me to do it myself.

My other creative inspirations both current and formative include: Peter Blake, Tove Jansson, David Hockney, Stanley Donwood, Al Colombia, Goscinny & Uderzo, Jerome K Jerome, Seth, HG Wells, Michael Kupperman & Matt Groening.

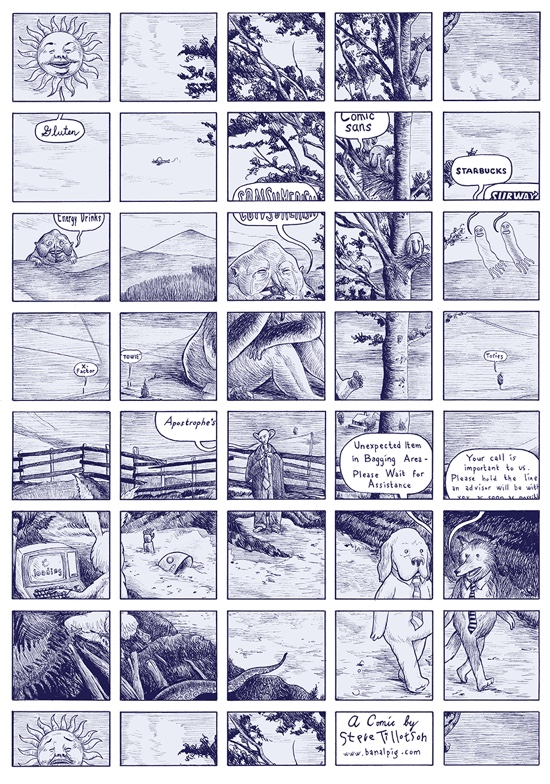

I want to ask you about the name Banal Pig, it feels like the word Banal ("so lacking in originality as to be obvious and boring" according to Google dictionary) is something you always interrogate with your work, poking the obvious and the ordinary and subverting it completely so that the obvious becomes the least obvious. Was that the idea? And why Pig?

ST: Banal Pig was pretty much my first comic character, and he evolved from a sketchbook doodle – I think he was called ugly pig at first before his character became slightly more nuanced. The idea behind the Banal Pig strip is that it’s an anti-comic strip – nothing happens, and there’s no punchline, but it looks like a comic, so it must be one. This idea came when I was still at art school and just starting to explore the medium of comics which is possibly why it sounds a bit pretentious, but I think it works. I’ve always had a fascination with pathos and banality, which were the major themes of my fine art paintings (usually of anachronistic mid-20th century photos), and the potential for adding narratives to this appealed to me as my work developed into comics.

Children’s Band

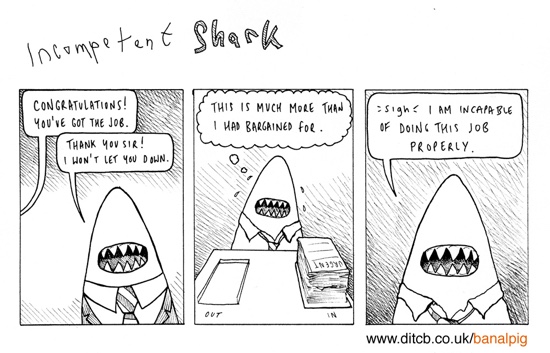

ST: I think the themes of banality and pathos are much more interesting to me, and probably more universal, than seeing somebody overcome the odds to save the world, and the great thing about the medium of comics is you can subvert the ordinary just by skewing reality a little bit, for example by making the character a pig or a cat, it highlights the quirks that we take for granted and shows how weird we all are all of the time.

Chris Sandwich

ST: Because the Banal Pig name was quite singular (and Googleable) I thought it’d be good for a first comic, and it stuck.

Can you talk a little bit more about how your fine art practice evolved into your more illustrative work?

ST: I studied printmaking at the RCA, but my work was mainly painting incorporating printing techniques such as etching and lithography. When I graduated, I no longer had access to printing equipment and painting on sheets of steel using enamel paints in our little flat was becoming a bit impractical, so I gradually moved away from the industrial solvents towards ink on paper.

I’d still use found images and objects to generate ideas though, but instead of the single painting which would have a sense of ambiguity, I’d have a specific idea about the image and follow the comic possibilities of that. An example of this is the Fez Man character, taken from a photo I found at a junk shop which I produced as both a painting and a series of comic strips.

At the same time, I’ve always doodled in a cartoony anthropomorphic way which is where the majority of my characters have come from; this was never really part of my fine art work (I think a few tutors frowned on my cartoony stuff so I learned to keep it separate).

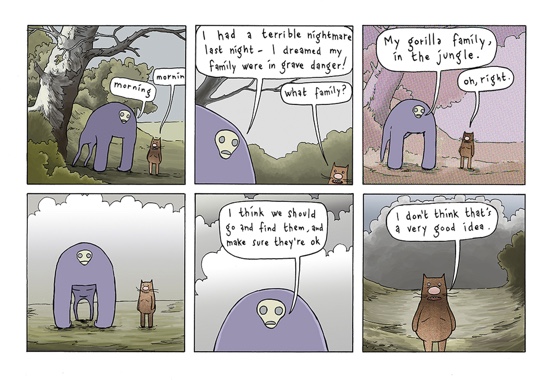

You’ve addressed that slight skewing of reality brilliantly throughout your work, whether it’s an incompetent shark, or a boy’s own annual story with really nasty themes alluded to in passing. But at other times especially in Untitled Ape, the plot lines tend to the more extraordinary and fantastical, just told in a deadpan normalising tone. What made you take this shift? And can you talk a bit about the mythological themes that came into your work and from where?

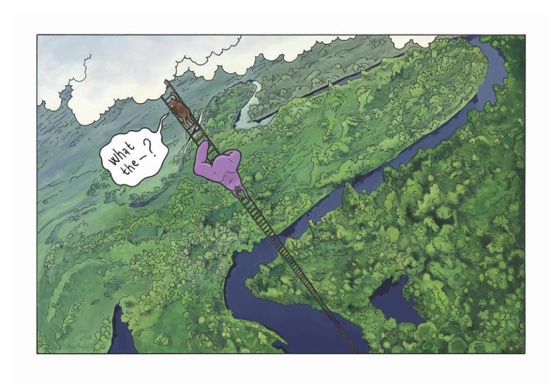

ST: Untitled Ape’s Epic Adventure was my version of a road trip buddy story, using the character of Untitled Ape and working backwards, trying to work out his backstory and using it to inform the narrative. Because he’s weird and ghost-like, these supernatural and mythological themes presented themselves, which gave me the opportunity to draw monsters and lots of other fun things.

I used a range of historical images of Hell, most notably from Hieronymus Bosch, but the notion of Hell in the book is deliberately woolly and not necessarily religious- it’s more like a shady business than a spiritual punishment. Likewise, the cloud community is not really Heaven, it’s more like a well-intentioned but slightly naff NHS-type service.

It was important to me that the characters were quite human (that is, flawed, obnoxious, confused, scared, etc.) to ground the story as hopefully their behaviour is relatable even in the bizarre situations they find themselves. For this reason, it felt wrong to feature humans alongside these characters, even though the landscape is recognisably human, so I worked the absence of people into the logic of the story.

Your work has consistently played with its own boundaries, I’m a particular fan of your pieces that divide a single image into a narrative by adding comic book gutters and speech bubbles.

How have you balanced creative work with day jobs and self-promotion?

ST: I’ve usually had non-creative day jobs, which I don’t actually mind that much because it means that when I make art it’s generally for myself and still fun. At my current job (at the University Of Bradford) I usually draw in my lunch break which keeps the momentum going. It was a bit intensive getting Untitled Ape’s Epic Adventure finished though, it took up a lot of evenings and weekends over last summer that I now owe my wife (and myself) back.

I was self-employed for the majority of 2012 however, trying to make a go of illustration, art and comics. It was, as all freelancers will know, a mixed bag – on the one hand lots of time and creative freedom, but also a never-ending gnawing sense of stress and trying anything to pay the bills. I lasted for just under a year before diminishing revenue streams forced me back to working for ‘the man’, but I came runner up in the Observer Short Graphic Story Competition around this time (Nov 2012), so that softened the blow a bit.

It was quite important to me at the time – it was nice to get a bit of recognition in a period where I felt I wasn’t really progressing in my career in comics. It was great to have my work in the spotlight for a while, but you have it in your mind that this sort of thing is the golden ticket, and in reality it didn’t really lead to any further opportunities, not directly anyway.

Like many creative people, you’ve strung your bow with many strings, and had to choose which to pluck hardest and longest (if you follow my metaphor) what main factors affected your choice of what projects to take on and which styles/characters to hone and develop?

ST: My time is quite precious as I work full time, so I try to do things that I’m passionate about – I’m not really reliant on an income from comics (which is a good job) so I want to keep it fun. However, I have been guilty of starting loads of projects, enjoying the honeymoon period and not then being able to finish them, so I had to make a concerted effort to finish Untitled Ape and not take on anything else.

When I chatted with Avery Hill about making it into a book, it was only a couple of chapters in and I’d been working on it on and off for more than three years, in which time I’d done loads of other bits and pieces. It was a big commitment to work on one thing for what was another couple of years and forsake all others, but it was at a stage where if I didn’t it would have never got finished. I’ve learned my lesson and now I try to be a one-project-at-a-time guy.

The process of crafting a whole narrative rather than pithy, immediate strips is a whole different ball game, and many a would-be graphic novelist falls by the way side aiming to run before they can walk. How did Untitled Ape’s Epic Adventure grow into a book from the initial stories in Banal Pig?

ST: As I mentioned above, I wanted to create a long form road trip kind of story, and Untitled Cat and Untitled Ape seemed the best characters from the Banal Pig universe to use as they already had a bit of history which I could potentially work into the narrative (more details here, although some of the links have gone weird).

I started UAEA back in 2010, and feeling a bit disillusioned with the small-press comics business model (see above) I decided to put it out as a webcomic for free (I wasn’t really making money anyway, so why not?). I was putting a new page out every week initially, and writing and drawing it as I went along. The schedule was a bit intense, and so when other projects came up it got put on the back burner and languished for a while.

When I came back to it (and wanted to make it into a book) I decided that just doing consecutive pages without a full story plan maybe wasn’t the best possible way of writing, so I took the time to work out the overall story arc, and added in more pages to develop more of the characters and generally make it a more satisfying read (listening to Scriptnotes, a screen writing podcast, also helped to polish the story). In this time my style had also moved on a bit, so I went back and tweaked some of the existing artwork and dialogue to make it all feel consistent.

How have your collaborations (notably with Gareth Brookes and Jemima Von Schindelberg) shaped your practice and your style?

ST: Gareth and I were on the same course at the RCA and we pretty much worked out how to make comics together – he has contributed story ideas and poems for the majority of my comics and I offered input into his, including anecdotes about myself that he used as gags for Man Man (his early stick man comics).

By the time it came to Manly Boys and Comely Girls, we were really comfortable and confident with each other’s way of working, and it was pretty straightforward really- we had a chat about the premise and came up with some ideas that made each other laugh, then we divided them up and got on with it.

With Jemima, we had an email back and forth after she bought one of my comics at a comic convention and the story developed quite organically out of our conversations. It came at quite a good time as I was looking to do something a bit more thoughtful after my first few Banal Pig comics which were out-and-out humour, and she brought an interesting perspective on the character of Ethel Sparrowhawk which I wouldn’t have been able to pull off on my own.

Likewise, how do you think your involvement in the small press and comics scenes in the UK has shaped your work?

ST: I think it’s quite hard to quantify my involvement in the comics scene – it’s always been based on doing interesting stuff and working with people whose work I really like. I’ve collaborated with and contributed to some great work from Jamie Smart, Jim Medway, Oliver East and others, and I’ve put together a couple of anthologies which had some really good stuff in. It’s great to see the breadth of work that’s around today, and social media makes it really easy to stay inspired (if you ignore all the Trump and Brexit stuff).

Practically, I decided a few years ago that I should stop printing fairly big runs of my small press comics as I wasn’t really interested in doing the convention circuit every week and barely breaking even, especially as I live in the north where they are relatively few and far between. In fact, one of the main reasons Hugh Raine and I put on the Leeds Alternative Comics Fairs (we did five events from 2010 – 2012 in a bar in Leeds) was to have a convenient outlet to sell our own stuff (but lots of other good creators were invited too). I always enjoy those events as social occasions but I’ve never liked the business side of it, so it’s been great to hand that over to Avery Hill for my last few publications.

What are your new/next projects for people to watch out for?

ST: I’m in no rush to launch into another major project, but my wife and I have been talking a lot about a story based on her childhood experiences in Scotland, so that may well be my next long-form book. Otherwise, I’ve just done a little two-pager for the Broken Frontier Yearbook 2017 and I’m tinkering away in my sketchbook and on short strips and pictures. If people really want to keep an eye on me, Twitter’s probably best.

Steve’s Twitter can be found at @banalpig. His work is loosely chronicled here. Untitled Ape’s Epic Adventure is available here