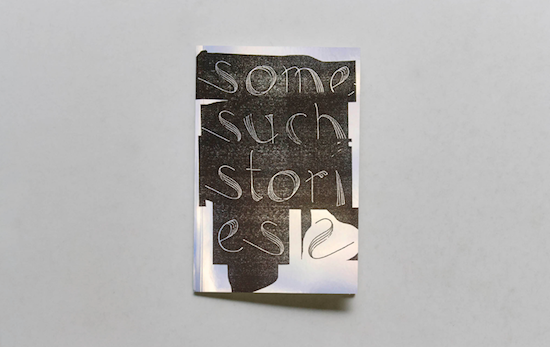

A bi-annual magazine now on its second issue, Somesuch Stories may seem like a vague title – but it’s a vagueness that fits its ethos perfectly. Rather than belying a lack of imagination, the void that the wrist-flick nonchalance of "Somesuch" conjures is actually more of a sweeping gesture – a statement of intent that to the reader, making it known that this is a journal always in flux, its idea of its own self always permeable. Fact and fiction, straight-laced and absurd, the eponymous stories diverge from one another in content and in tone more often than not. What they share, however, is an intention and a desire to say something worthwhile.

In Secret Ceremony, Mia Farrow plays a wild-eyed, maybe backwards young woman who’s fucking (or else being fucked by) her stepfather; meaning that Farrow was, in that despicable way, playing her stepdaughter Soon Yi before she had even met Woody. As Cenci, she has the very particular look of dishevelment so often used to suggest someone fathers might fuck, and the very particular style of the Sixties — the peter-pan collars, the baby-doll dresses, the pale legs, the long hair with “bangs” and the clavicles — that says much the same thing. The film was made in 1968, but has the fin-de-siècle gloom and the sexually paranoid spirit of the summer of 1969, and is directed by Joseph Losey — while it’s possible to argue that between, say, 1961 and 1972, all women were daughters and all men were Daddies, conceptually speaking, Secret Ceremony plays it as literal.

Played by Elizabeth Taylor, the interloping prostitute who resembles Farrow’s character’s mother (who is, in the way all decent older women ought to be, deceased) is undone by her weight and her middle age: she no longer looks like a girl or a daughter, but only a mother, cutting her out of this sick Daddy/daughter-girl binary. “You look more like a cow than my late wife,” the stepfather tells her, despite the fact that what she looks like is Elizabeth Taylor. “She was well bred and rather frail… except for her famous mammalia — oh, excuse me, that’s a private joke in questionable taste. Still, sometimes one has to choose between good taste and being a human being.”

By contrast, even when playing a mother to Satan’s son, as she does in Rosemary’s Baby, Mia looks like a daughter; her eyes are the cornflower blue of a baby’s — the same huge size, with the same blonde lashes. In Secret Ceremony, her father figure is played by Robert Mitchum, who is maybe the ultimate Daddy: a serial seducer of students, his lecherousness is less failing than foregone conclusion. His facial hair implies that he’s wearing a store-bought pervert costume, and makes him resemble a wolf or a sentient hard-on. He is, like Rosemary’s Baby’s Daddy, also the devil. “Do you realise,” he howls, as if nobody has ever made a saner, more convincing proposition, “that all over the Australian bush, fathers are bashing their daughters like there’s no tomorrow?”

In the end, it’s always Daddy who leaves out white roses, Daddy who slinks his way back to the house, Daddy who touches you while he’s invisible. Daddy’ll yank on your hair, if you like that particular thing. Other things. Other places. What flesh-and-blood man can compare to a spectre? Daddy’s a ghoul, so nothing touches him: all teeth and hair, and a dick like — in practice, if not in appearance — an anglerfish lure, but no trace that might stick (or none, anyway, that they can see), so he’s basically ether. An idea. He possesses every man that comes after him, whether they sense it or not. Every male body. Every male face. Every well-meaning male glance. Every man who wears the same shoes, or the same cologne; every body the same kind of shape. It’s a special, unusual power, this power of Daddy’s — a big, male omnipotence, wielded so bluntly the trauma leaves brain damage: Post Traumatic Stress, Daddy. “Farrow [performs with] an emphasis on facial expressions,” says Variety, which is true of both crazy people and women who’re trying to signal for help without moving their bodies. Girls whose eyes look like rattling pinballs are always hungry for something.

When filming Rosemary’s Baby, Mia Farrow weighed 98 pounds, though Polanksi — another mean rapist Daddy — suggested she diet herself down to 90; so really, he was telling her to erase yourself, Mia. Undo your Self. Hollow your outline. There are men who really get off on the idea of female erasure, and they’re Daddies — all prize-winning, thoroughbred Daddies. The biggest, most brutal offenders. They’re fascists. When Cintra Wilson calls Hollywood “blood-drunk,” it’s this she refers to: a district of vampires shooting day-for-night, so you know they can walk in the sunlight — using young girls as replacements for missing reflections, and draining them dry like they’re juice boxes. It’s the blood loss that gets them so small and so white, the way Vogue likes them: typical, Caucasian cover-girl pallor. Now, in 2016, Blake Lively uses her Hollywood platform to talk about working with Woody as being “empowering,” so you figure out how the men get away with it. People say that power is an aphrodisiac, when what they mean to say is a great, male weapon. The Daddies in Los Angeles wield it.

Renata Adler, reviewing Secret Ceremony for The New York Times, expresses a wish that “a presence as delicate as [Farrow’s] were allowed to play somebody normal for a change” — “from Rosemary, the lapsed Roman Catholic neurotic, to this doomed, loony child,” she continues, “must be a harrowing professional route.” Adler is nobody’s fool, and no bad Daddy’s daughter; she sees things and takes them to pieces as if she were Daddy. Renata Dadler. It’s true that Mia is always less bodied than everyone else in the picture: one thinks of Alice Gregory’s description of the anorexic as “a modern-day phrenologist, searching for saintliness and vice in the bone structure of strangers,” not because Farrow is thin — though she is — but because of the very exceptional style of her thinness; not thin like a film star, but thin like a saint.

There is a difference between the religious form of anorexia, i.e. mirabilis, and the civilian brand of “nervosa,” which helps all the nervous daughter-girls whittle themselves into toothpicks. While filming Ceremony, Farrow stayed in Grosvesnor Square, in the flat where she and Frank Sinatra had spent their honeymoon: having deserted him since, her loneliness ate her like cancer until there was nothing much left (the first thing he’d said to her, ever, was: “how old are ya, kid?” He wore the same cologne as her father). “If you kill yourself,” her secretary had told her then — clearly believing it possible — “I will never forgive you.” She lived, but she lived to meet Woody, which only meant more pain; another dark Daddy, whose viciousness left her feeling at best dumb, at worst a doomed loony. “She told friends he once lit into her in front of the Russian Tea Room because she was off four degrees on the weather,” Vanity Fair reported after their split, “and another time because she was unable to tell him how many kinds of pasta there were in the world” — this as if he were schooling her, teaching her science and home economics between movies. A home school of hard knocks.

(“The truth,” he told her, after the Soon Yi affair, “doesn’t matter. All that matters is whatever people believe.” What people believe, in Hollywood, is Blake Lively.)

Grief, as anyone who has ever lost someone they loved with their whole heart will tell you, is rarely finite; rather, it multiplies over and over again, so that any person can hurt in a hundred ways, for a hundred reasons, and never run out of it. Being alive is death by a thousand cuts — an 80-year Lingchi, with luck: with less, 57 or 69. Or, like this film’s Cenci, 21, taking your overdose with milk like a sick child and howling for Mother. “Crazy people never look their age,” says the girl’s Aunt Hannah; which is fortunate, as if they did, who would love them? Daddy might insist that you’re always his special little girl, but it’s the little, the girl he desires. “The ‘youth’ that the Spectacle has granted the Young-Girl,” Tiqqun assures in Theory of The Young-Girl “is a very bitter gift, for this ‘youth’ is what is incessantly lost.” In Mia’s own memoir, the first line is “I was nine when my childhood ended,” which I expected to mean that she suffered abuse, when in fact what she suffered was polio. All her life, I realised, she’s grieved for her youth.

When Mia lopped off all of her hair, Dalí called it a “mythical suicide” — I don’t know what Woody Allen thought of her various hairstyles, though record shows that Frank Sinatra preferred her more feminine. “I loved that hair, man,” he gushed. “It was definitely the [long] hair that got me.” So Mia, to spite him, went gamine. “I picked up a pair of scissors,” she said, “and cut my hair to less than an inch in length”; and it was, for Farrow, a girlie castration, or like she was cutting her tongue out: an un-secret ceremony exorcising the demon of Daddy. “She walked over to me, and held up her hand full of hair from her head,” the director Jeff Hayden, with whom she was on set for Peyton Place, told the New York Post. “And she said, ‘Jeff. No more little-girl stuff.’ And handed me all of her hair.” The haircut didn’t, of course, succeed in killing her daughter-girl incarnation, which lived on to tremble its way into marrying Allen and batting her lashes as Daisy Buchanan. Even Farrow and Frank Sinatra’s sex life had supposedly been adolescent: he — allegedly — suffered from premature ejaculation, and she — allegedly — faked her orgasms (Google “Mia Farrow Woody Allen sex life” as I just did, and the major hits are all about molestation).

The reason that Mia’s sad young suicide in Losey’s film is called Cenci, I discovered, is historical. As executedtoday.com has it: “On the morning of September 11th in 1599, the Cenci family — mother Lucrezia, son Giacomo, and the immortal, tragic heartthrob Beatrice — were put to death at Sant’Angelo Bridge for murdering the clan’s tyrannous father. Francesco Cenci, the victim, was more accustomed to mzaking victims of his own: detested around the Eternal City, he indulged his violent temper and fleshy lusts with the impunity of a wealthy cardinal’s son.” Beatrice tried to argue to the authorities that her father — her rich, tyrannical Daddy — was really a rapist. His power meant that nobody cared, and when her body was taken out after her execution, headless, her covering fell off so everyone saw her stark naked. This does not, you have to admit, feel un-Hollywood-like: one more naked young girl sacrificed to the whims of a well-known man. It’s a story older than Frank, or Woody, or Roman. Sometimes one ends up caught between a rock and a hard place: being —or fucking — Daddy, and being a human being.

The latest issue of Somesuch Stories is out now and available to buy here, and more writing – on a verifiable gamut of topics – can be found on their website.