Alexander, 38, and Mike, 30, have been in the U.S. for only a few months, but they hope to never have to return to Russia. They’ve filed an asylum claim requesting permanent residence in the country, and are now waiting out the days for a decision.

We met on a dating website. It was November 26, 2010.

Mikhail mentioned that he wasn’t ready to meet for dating or anything serious. But it was the same for me. I just had in mind meeting up to talk. Nothing serious. It was the pictures of his dogs that caught my eye. I remember I asked him about them, what kind of dogs they were, because I love dogs. That’s how the conversation started. I was working as an administrative assistant at the time, so I didn’t like going back and forth on email. All these long messages about nothing. So I asked him to meet.

The next day it was cold and snowy. We’d made a date and then almost the last minute he was trying to cancel, but he wouldn’t explain why. We texted all day and finally he agreed to meet. Later I found out it was because he was broke. But being independent, he didn’t want anyone pay for him.

Finally we met in the center of Moscow near the Tverskaya metro. I got in his car and there was this feeling that we’d known each other for many years. There was no discomfort or anything, none of that awkwardness there is sometimes when two people meet for the first time. We went to a restaurant close to his work. We didn’t notice the time fly as we sat there until the restaurant closed. We moved to a twenty-four-hour café to continue our conversation. That night we told each other everything about ourselves, not hiding or whitewashing anything. Neither of us wanted to part, not then, not later, and never again.

At the end of the night we didn’t want to leave each other but it wasn’t a fairy tale either. Mike was in a relationship and didn’t have his own apartment, and neither did I. At the time, I was renting a small room with a roommate. Neither of us were happy with the idea of living apart and having an affair. Mike’s relationship had gone sour a long time ago. The next morning, we decided that he was going to move in with me. I picked him up that evening and since then, we’ve lived together and haven’t left each other’s side even for a day.

At that point I already had tickets to DC for December 8, to go visit afriend. There was no question: Mike had to go with me. It was the first visit to the U.S. for both of us. It was very difficult to buy him tickets and get a visa on such short notice. My friend we were visiting told us to bring suits because there would be a special event. The day after our arrival we went to this event, something we never thought we would see. It was a wedding, one of the first gay weddings in Washington, DC.

And it was amazing. One of the guys was Russian, and his husband was from Texas, a typical American, a big burly guy. The wedding was like the ones in the movies, with limos, romantic vows, beautiful guests, and happy American parents, at the National Cathedral. The reception was at a glamorous hotel. It turned out that Mike had dreamed of it since childhood, and was sure that it would never happen because of Russian culture and its laws.

Seeing that it was possible made a big impression on him. Not least, he was moved by the smiles from the people on the streets, some of whom even stopped to congratulate the grooms. There was not a single malicious gaze or gesture in their direction. People behaved just as people do when they usually see two people in love getting married: they were smiling, happy for them! That’s when Mike asked me to marry him. I said yes.

The next day, on December 10, we went to apply for a marriage license. They approved us, but the closest date we could get was December 17. We didn’t spend any time waiting or testing our relationship. December 17 is our anniversary. We had lot of friends telling us not to do it, to think of all the future problems we might have in Russia, but we ignored them. We couldn’t explain it; it just felt right. We both knew it was that we wanted.

After that we went on a honeymoon to Miami for a week, driving there and back. It was crazy, a really long drive, and there was a big blizzard. When we got back to DC, Mike found out he’d been fired. His colleagues had somehow found out he’d gotten married, probably from Facebook, since he’d posted some of our wedding pictures. He was happy, and he wanted to share that with his friends. He’d been working in the marketing department of a major TV network. While we were in Miami they sent him an email telling him that he no longer had a job.

When we got back to Moscow everything was awful. Terrible weather, everybody unfriendly, a general gloom over everything. We had nowhere to live and Mike was out of a job. We ended up finding an apartment with a new roommate; he was wonderful, everybody loved him. We all lived together for a year and then he was murdered. The details are still shady and nobody knows exactly what happened that night. He was back in his hometown visiting his parents. That Monday, we were supposed to go hang out with his boyfriend, whom he’d planned to marry in Europe that fall. Sunday morning, they found him on the road not far from his house with a shattered skull. No one knows what happened. They say that he came out to someone. The police didn’t really bother to investigate. We couldn’t live there anymore, everything in that apartment reminded us of this wonderful person. It was too hard.

In February 2011, Mike started up his own business, and it was growing fast. In the summer of 2013, the Russian government closed down the international organization I was working for, and I became temporarily unemployed. About a month later, people from the Federal Security Agency, the FSB, came around and started asking me questions. They basically asked me to apply for another position at my old job and be their person on the inside.

Back when I was employed, our organization’s security services could have taken care of this kind of thing, but now it made me nervous. The following week they visited Mike at his office and tried to intimidate him into pressuring me to do it. They explained that they knew everything about our relationship and that we were married. Then they returned to me, trying to scare me, telling me the trouble we could both get into if I didn’t agree to work for them. They explained very clearly that the new laws would make it “no problem” to arrest us. From there, it was not far from the courts, especially considering the fact people like us “should be shot anyway.”

No one expected it to escalate from words to deeds. A few days later, Mikhail was kidnapped and beaten up, threatened with a gun, and dropped off in a Moscow park. He wasn’t robbed. They didn’t take his money or even his phone, they just switched it off. The men who attacked him told him that he needed to pressure me to do what I needed to do. That’s when we decided to get out as soon as possible. Now we are in the States, and no matter what happens, we are hoping for the best.

Before all of that happened, this new law had just seemed absurd. It doesn’t work. It can’t work. However, as the FSB agents explained to me, they can use it against us. After all, as a gay couple, we’re a walking violation, the propaganda for, as they call it, “nontraditional sexual relations.” It turns out that in Russian society and under the present administration, loving each other is nontraditional. What the government wants, and is getting, out of the anti-gay law is to turn the public against gays and lesbians as a group.

I’m not sure what impact it has on our day-to-day lives. We’re not activists, we’re not going to Pride. I don’t know if that’s good or bad, but that’s us. And it’s not just this law. It’s so many other things that wear you down.For example, I tried to get another bank card for Misha–not a credit card, just a debit card–for access to my own money. It was impossible! The tellers simply had to know why I wanted to let this guy use my account. Why is it their business how I use my money? Even when you have money, you still can’t have a normal life. It’s crazy.

Russia has a lot of problems. One of the biggest ones is the general lack of human rights for its citizens. Only the government has rights. Many groups of people have none at all: the elderly, children in orphanages, the incarcerated. This law is a tool for manipulating the public. It’s supposed to make people think that gays want something special–special rights, special relationships, special marriages. It’s being used to distract people from all of the other problems in our country.

Before the FSB intervened, we were living our lives. We had our problems like anyone else, which were made worse by the owners of the apartment that we were renting, kicking us out when they saw that we shared a bed. Otherwise, Mike worked. Sometimes we went out to bars on the weekend. We had a few friends, but we had kind of left our previous life behind. The life we each had before we met each other. So we didn’t have a ton. But we went out, went to the movies. We liked to drive out into the country. Normal stuff.

People always say good relationships never come from a dating website. But look at us, we met online, and neither of us was looking for a relationship. It happens, there’s a spark. If you meet the person you want to live with, who you love, you have to fight for it.

— As told to Joseph Huff-Hannon

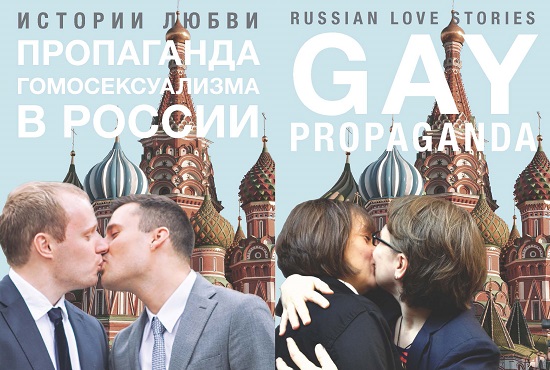

Gay Propaganda is a collection of stories, interviews and testimonies about the lives and loves of LGBT Russians living both in Russia and in exile. The moving, heart-felt and sometimes funny tales of long-term commitment, dating and daily life offer an intimate window into the lives of Russians persecuted for who they love.

Gay Propaganda is published by OR Books, and is available to purchae here via their webiste.

The book is printed in both Russian and English, with a Russian language ebook being made available to download for free for the purpose of distribution in the samizdat tradition of publishing and sharing banned books