In 2005 a friend was bemoaning Slint’s decision to reform in order to curate All Tomorrow’s Parties. Before this sorry weekend it had been easy to get boys to talk to her; all she had to do was wear a Spiderland T-shirt to a gig or a club night. They were drawn, moth-like to her. Here was a girl who clearly understood.

However the reformation affected the standing of the Louisville, Kentucky four-piece (people were perhaps less hushed when talking of them afterwards) and the desirability of my friend (there were less male heads turned caused by an abundance of next generation Slint shirts) Spiderland remains a rite of passage album for those serious about serious indie rock. Back in 1991, milestone alternative rock albums were being released left, right and centre. My Bloody Valentine’s Loveless finally saw the light of day but it felt more like the final nail in the shoe gaze coffin, rather than the birth of something new. R.E.M.’s Out Of Time proved that mainstream indie had all but lost its way. The Pixies, we are continuously told, ‘came up with’ a loud quiet loud formula but by 91 and their final album, Trompe Le Monde, this had all but gone, replaced by the loud louder loud reinterpretation of Nirvana’s Nevermind.

Instead it was a difficult album – that no-one really seemed to care about and no one bought at the time by a band who split up as soon as it was released – that would cast a long, if somewhat spindly, shadow across the new decade.

Of course, it seems almost odd that Continuum have waited until book number 75 to tackle Spiderland. And at first, it seems like Scott Tennent, a senior writer and editor at the LA County Museum of Art and the Pretty Goes With Pretty blog, has signalled his inability to cope with the project in hand by ignoring the brief and writing about Slint’s entire (original) five year history instead of their key album. But really Slint’s ordinariness is integral to the story and Tennent does well to stretch it to 147 pages. But you have to remember that whatever sky-scraping plaudits have been heaped on it since, it didn’t exactly set the world ablaze when first released selling just a couple of thousand copies in the first year (it has gone on to sell 50,000). It generally wasn’t held to be that much more important than Bitch Magnet’s Umber for example, and, in all probability, would have sunk without trace if it wasn’t for the inclusion of ‘Good Morning, Captain’ on the OST of Larry Clark’s Kids and Steve Albini’s relentless pimping. (He gave the album “ten fucking stars” in a review he wrote for Melody Maker, that was both prescient and heartfelt.)

With this in mind, it is unsurprising that people’s recollections are hazy meaning the interviews are sparse and contradictory and mainly consist of people talking about rehearsals. Wisely he chooses to dismantle the few myths that have sprung up around the recording (that several band members were institutionalized by the intensity of the recording process – an urban myth which does little other than to reveal the narrow horizons of some indie rock fans). Of course, the ordinariness of Slint’s story is central; it gave them some of their brutal power. After a polychromatic alternative 1980s Slint quietly signalled a new way of doing things for those paying attention: a pianissimo fortissimo pianissimo (spread over an album as much as a song) approach to volume control, and similar contrasts in vocals (whisper, scream, whisper), subject matter (serious, goofy, serious), guitar FX, texture, time signatures etc etc etc.

Once the author has dealt with the tangled genesis of the group, what the various members went on to achieve afterwards and lengthy descriptions of all their songs there isn’t much room left for him to manouevre in but there are still a few breadcrumbs of scintillating detail to ingest. The best of these passages describes how a pre-Slint Maurice (featuring David Pajo and Britt Walford) went on tour with Glenn Danzig’s Samhain with none other than Will Oldham (who would go on to be responsible for the iconic Spiderland cover photo among other things) as roadie. Both Walford and Bonny Prince Billy had Misfits style devil locks (perhaps explaining why he is now bald) and did little other than talk about Danzig, so to be invited on tour with them was a dream come true.

“Offstage Walford and Oldham would entertain the Samhain guys with their impressions of people with cerebral palsy (bear in mind they were fifteen); Danzig sat on a porch in Bloomington, strumming a guitar and singing ‘I was born with a small dick’ to the tune of John Cougar Mellencamp’s ‘Small Town’ (bear in mind he was thirty-one) – eminently profound experiences for the Louisville juveniles.”

And given that it was Slint as a concept (one that certainly includes their single track ‘Glen’ as much as ‘Breadcrumb Trail’ or ‘Washer’) that went on to be so important to the continued progression of post hardcore and the efflorescence of post rock, Tennent is ultimately proved to be right. (Even though his insanely over-extended note by note description of their most famous track ended up provoking the same angsty and nervous reactions in this reader as listening to ‘Good Morning, Captain’ itself does. Something which may well have been the point.)

And from a minimalist, obscure, dour, pre-internet, word of mouth start to leftfield indie rock in the 1990s, Continuum pull a blinder by choosing the altogether more world bestriding, maximalist, inextricably tied to the internet, fin de siecle summoning, not to mention multi-million selling Kid A – as the subject for volume 76.

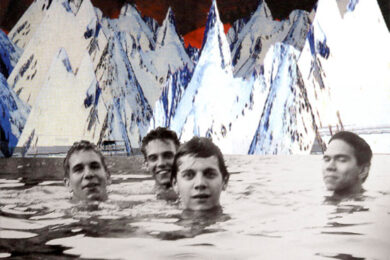

Marvin Lin, a co-founder of Tiny Mix Tapes and a former editor of Pitchfork, hits the ground running by accurately recalling the insane amount of hype that preceded the release of Radiohead’s fourth album. He paints a vivid picture of allowing himself to become a bubble of inflated pomposity (something that will chime with a lot of people reading) in the weeks leading up to the release in 2000 by outlining how he saw the album as a chance to achieve hitherto unimagined levels of sublime transcendence. This is a bubble of pomposity he takes great pleasure in taking a pin to:

“On October 3, 2000 (midnight October 2), I purchased Kid A at a record store and rushed back to my dorm room, fast walking like a fucking fanboy idiot. I was so excited to finally enact the ritual. I proceeded to put on my headphones to block out any potential disruption, flicked off the lights, and closed my eyes… all the waiting, all the teasing, all the hype, all the research, all the anticipation, all the asceticism, all the enthusiasm had combined to create what I believed to be the perfect disposition for pre-transcendence, the ideal state of mind to sponge up Kid A.

But I was wrong. Not because of the impossible expectations I had for the album, but because the whole ordeal wore me out.

So I fell asleep. Twice.

I FELL ASLEEP TWICE DURING MY FIRST LISTEN TO Kid A.”

While it’s true that Lin has a wealth of source material to refer to, manipulate and deconstruct (compared to Tennent especially), he certainly sets about his job with relish and intelligence breaking the book down into nine chapters with titles such as Kid Authenticity, Kid Aesthetics and Kid Apocalypse; dealing with the album in terms of themes, while sticking to a straight-ish, user friendly narrative.

Among numerous subjects touched upon by this book is Radiohead’s engagement with so-called IDM, whether they could still be called a rock group anymore and if they weren’t… then what they hell were they? (This leads into an amusing recollection of some of the more fevered attempts to pin down just what was going on. Bear in mind that even though they’ve gone to some lengths to distance themselves from it in the intervening years, even WIRE were fascinated by what Radiohead were going through and gave them a front cover because of it. In fact one of the few notable press reactions at the time not mentioned here was that of Nick Hornby who described it as being akin to Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music proving, yet again, his complete and overwhelming unfitness for purpose, even as a lowly music hack. Out of all the examples cited, the crowning example of critical overreach has to be Chuck Klosterman’s assertion that Kid A successfully predicted 9/11. And if Melody Maker got it right with Spiderland oh boy, did they get it wrong with Kid A. But at least the MM had the guts to call what it saw as a naked emperor as regards to a tremendously popular band; where most shrugged, played guess the genre or said, LOL, people will love this in a decade’s time… i.e. it was the same old story – most music journalists didn’t have the nerve for a snap decision and even the few that did, mainly called it wrong.)

Lin gets stuck into some cultural theory without coming completely unstuck, describing time and music as abstracts and… well, it’s all well and good but unsatisfyingly, he never quite gets as far as nailing exactly why Kid A was a quantum leap forward in popular music, as opposed to say, Endtroducing, Selected Ambient Works or some other critically lauded touchstone of the 90s.

Anything that makes us remember what these two albums sounded like when they came out (or when we first heard them) is a good thing, and personally I enjoyed taking a day long trip down misery lane. Both books are a success and they stand to be read together but Lin’s book is smart enough to rank alongside other personal favourites from this series that include Drew Daniel’s 20 Jazz Funk Greats, Christopher Weingarten’s Nation Of Millions and Hugo Wilcken’s Low.

And of course all of this leads us to one conclusion: that very soon Continuum are going to announce numbers 77 and 78 in their impeccable 33 ⅓ series: Ice Cube’s Death Certificate and Outkast’s Stankonia, for example, because today’s not just white boy day and the 1990s weren’t just about indie rock… right?