All photographs by Barry Plummer

This is an adapted extract from Paint My Name In Black and Gold, out now on Unbound

The Black October tour of late autumn 1984 was a recipe for disaster: a fracturing band, containing a singer with a predilection for pushing himself past the limits of his endurance, on a gruelling six-week slog around the UK and Europe. Three dismal and disastrous festival dates in September, at a muddy German motocross arena, a former Nazi open-air arena and a windy North Yorkshire racecourse – and the cancellation of a fourth in an historic art deco cinema in central Paris – had not boded well.

Before embarking on Black October, Eldritch met Adam Sweeting of Melody Maker for pizza in High Holborn. Eldritch made no secret of the fact he had been sick. In the studio, ‘people he engaged in conversation began to change colour and bend out of shape,’ Sweeting recorded. Eldritch had been hospitalised and then placed under the care of a doctor in London who was seemingly aware of the nature of his drug intake and his utter disinterest in relaxation. As Eldritch has recalled, ‘The doctor said “How do you relax?” and I said I don’t. He said, “Well, wouldn’t you like to be able to relax?” and I said no. And he said, “Take these.”’

Without the prescribed tranquilisers, another collapse was imminent. There was also realpolitik: rather than abstaining, Eldritch would adjust his amphetamine use before his body informed him, ‘No thank you. This has gone far enough. It’ll end in tears,’ as it had done at Genetic Studios. With food and daylight back on the menu, Eldritch put on a stone and a half in weight and his blood pressure, heart rate and blood sugar level all returned to virtually normal. Yet, even back to his usual eight and a half stone, Sweeting observed that Eldritch still looked ‘as overweight as a credit card and his complexion remains a brilliant white’. It was by no means certain that Eldritch could physically complete the October tour.

Nor was it at all clear that the band itself could make it to the end without splitting apart. Gary Marx, one of the guitarists and a founder member, was already halfway out the door and Wayne Hussey, the other guitarist and Craig Adams, the bass player, found it increasingly hard to tolerate Eldritch’s high-handed manner and his froideur (or “him being really fucking annoying’, as Adams puts it.)

It seemed there was every possibility that the Sisters of Mercy were in their humiliating last days.

Incredibly, much of Black October was a triumph. The Sisters played longer and more varied sets than on the spring Pilgrimages, their tours of the UK and Europe earlier in the year. Most of what would become the first side of First And Last And Always was a regular feature, mixed in with all their singles (minus ‘Temple Of Love’ and ‘The Damage Done’), plus ‘Burn’, ‘Heartland’, ‘Emma’ and ‘Gimme Shelter’. A new cover – ‘Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door’ – as blackly humorous as it was magnificent, was played most nights and was regularly Hussey’s masterpiece.

Although there was a musty sense of déjà vu as the band found themselves back in many of the same towns and same venues as previous tours – the Odeon in Münster, the Top Rank in Plymouth, Rock City in Nottingham, the universities in Sheffield and Manchester – there was evidence that the band were on an upward trajectory: they headlined the Refectory at Leeds University and the Lyceum ballroom in London for the first times. Sometimes, when they broke new ground the response could be rapturous. Hussey remembered that in Colchester, at the University of Essex, ‘we sold out and the crowd went nuts.’

Their crew, an extended ‘family’ of sorts and the support network they provided – critically absent in the studio – were restored during Black October and were essential to its successful completion. The key off-stage relationship was between Eldritch and Pete Turner, the sound engineer. Visually, they were an odd couple: Turner, a giant who dressed like a trucker, Eldritch, small and skinny, perpetually in his rock ’n’ roll regalia. Turner liked Eldritch enormously and thought he was in his natural habitat, despite the toll it was taking on him. ‘He had star quality. It never occurred to me he shouldn’t be there,’ Turner says. ‘Big Pete’ and Eldritch were the two ranking adults on Black October. If Eldritch needed to discuss whatever was winding him up – and there would always be something – it was Turner he went to most often.

Turner was quite aware that Eldritch had come on tour nowhere near fully recovered. Being the ‘tour Dad’, as Turner puts it, sometimes meant he had to put a metaphorical arm around Eldritch. ‘Pete was very conscious of what Andrew was going through,’ says Phil Wiffin, the lighting designer. ‘He wasn’t well. The amount of drink and drugs that were going on, that creates its own stress… Pete would often try to get him to take a break, not mollycoddle him, but give him a shoulder [but] Andrew was a difficult person to support. He needs it but he’s reluctant to accept it. He was quite a difficult character in that time period… He was a quiet, shy guy.’

The importance of Jez Webb, one of roadies, on band and crew morale was also vital. Eldritch has described him as ‘an all round superhuman good guy… relentlessly cheerful and amicable.’ Webb too was aware of the pressure Eldritch had placed himself under. ‘Andrew created a character, a very cool persona that was very hard to let your guard down with. The more the band went on the more that character took over. He’d be as daft as us in the early years but I’m sure he became more aware as the band grew, what people expected of Eldritch. We all dipped in and out of living the Sisters thing, but for him it was 24/7.’

The gigs were often a potent mixture of adulation and contempt that created its own peculiar energy. Black October, even more than previous tours, seemed to pit the band against elements in the crowd. Someone swiped Eldritch’s glasses off his face in Leicester; spittle and bottles were launched at them in Glasgow; spit alone in Cardiff, which especially infuriated Eldritch, who already had an irrational dislike of the Welsh, perhaps related to a head injury sustained in a Welsh playground as a small child. Eldritch often seemed genuinely irritated by people in the crowd. The headmaster in him would often bark out, ‘Shut up!’, as if he was taking assembly. Sometimes there was added acid: ‘We’re not here for conversation, so keep it quiet’ and ‘We’ll do the singing, you do the jumping up and down.’

Some of it was serio-comic stuff. Eldritch opened the Lancaster gig with, ‘Let’s get the heckling over with now. I can take it. Come on,’ before tossing out his own invective: ‘This one’s for the bastards still playing pool. I can see you. I know who you are. I have your addresses.’ His introduction of ‘Heartland’ as ‘a song about roads and stuff; mainly stuff’ was greeted with, ‘Bollocks! You fuckhead!’ Eldritch, obviously inebriated, shot back: ‘I’m afraid, fella … if you choose to carry on with that sort of behaviour, there will be retribution,’ and after a pause for effect, ‘of the severest sort.’ However, sometimes Eldritch’s threats sounded in earnest. In Nottingham he noted: ‘Something we’ve learned in our many years is that the right hand is a horrible thing to lose; I’d retract yours, my man.’

Eldritch could also be self-deprecating. After ‘No Time To Cry’ in Stuttgart, he observed, ‘I like the title better than the words’ and after ‘A Rock And A Hard Place’ in Edinburgh, ‘You’ll get used to it. Not sure I will.’ At Rock City, a member of the audience enquired about his physical health. ‘I’m not anorexic, all right. I’m compact,’ came the reply. Doktor Avalanche the drum machine misbehaved so badly in Nottingham that ‘Burn’ began three times before being aborted, requiring the band to leave the stage to ‘tend to our machinery,’ as Eldritch put it.

Touring at the Sisters’ level was still not without its hazards and the possibility of accidents and violence. ‘There was a team effort to get from A to B, do what we had to do and then get out of there without getting injured,’ recalls Wiffin. ‘I got bitten on the leg at one show by a German guy as I was stood on a riser in front of him.’ In Europe, there were instances of genuine danger. At the Schlachthof in Bremen, Hussey recalls Neo-Nazis ‘chucking stones and rubble onto the flat roof. It sounded like a particularly heavy hailstorm.’ They then got into the venue and ‘fired a flare gun at us and it set fire to the backdrop,’ Adams remembers.

On stage during Black October the Sisters Of Mercy were a potent rock band, but off it they were terminally divided. Hussey and Adams remained playmates but Eldritch and Marx separated themselves from them and each other. To Wiffin, the disintegration of the band was obvious: ‘I was aware that “the family” was breaking down.’ Hussey and Adams indulged their ‘classic rock ’n’ roll approach’ as Wiffin terms it, whereas ‘Mark (Gary Marx’s real first name) would definitely gravitate towards the crew and Andrew, if not with a woman, would disappear for a while or sit with me and Pete.’

Sometimes innocuous activities could become a mote in the eye. ‘We’d go somewhere in Germany and Andrew would tell me what I needed to know about food,’ Turner says, ‘but he used to let the others get on with it. They had all sorts of weird food. That used to annoy Craig that Andrew used to be able to order stuff and get what he wanted, whereas they would order pigs’ heads – quite unpalatable stuff.’

An outbreak of pubic lice on Hussey and Adams also did not help relations within the band: ‘Andrew refused to get into the vehicle with us,’ Adams admits. Eldritch shunned the Flying Turd (as their Dodge minivan was nicknamed due to its brown carpeting) and instead travelled in the car with the crew. He insisted Turner call his wife, who was a nurse, to get medical advice and then acquire the necessary treatment from a chemist’s. ‘There was quite a posh lady behind the counter,’ Turner recalls. ‘There’s a couple of friends of mine have crabs,’ he told her. ‘She gave me that knowing: “Couple of ‘friends’ of yours, sir?”’

Wiffin additionally suggested the wearing of shower caps as ‘the correct health and safety clothing for dealing with crabs.’ Adams and Hussey ‘had to travel creamed up’ (as Jez Webb puts it) in the Flying Turd in only their underpants and shower hats. They played the next sound-check in their entirely useless – as Wiffin well knew – headgear to peals of laughter from the whole crew.

Adams thinks he caught crabs when he had to sleep in Hussey’s bed – he’d thrown his own out of the hotel room window. This was also the fate of a wardrobe on Black October and Marx claims responsibility: ‘I was always fit but somehow managing to fling a wardrobe into a tree outside the hotel in Birmingham still astounds me whenever I’m reminded of that one.’ Dealing with this also fell to Pete Turner. ‘I had to go down the next morning and tell the landlord/hotelier: “Sorry, there’s been a wardrobe broken.”

‘“No worries, I’ll pop up and have a look.”

‘“Actually, you might want to go out into the garden …”’

As well as sound engineer and de facto tour manager, Turner functioned as the authority figure for the whole crew, which ‘he ruled with a tough fist and heart of gold,’ Merb, another of the roadies, says. Since Turner could ‘pick up speaker stacks as if they were paper,’ it made sense to obey him.

Turner had no real interest in accompanying the band or crew in any after-hours fun. Ministering to the band’s recreational needs was the role of Dave Kentish, their driver and owner of the Dodge minivan; Kentish’s background in security was useful should meaningful threats of violence be required. His handling of the Flying Turd could also be equally unnerving. Merb recalls sitting next to him when he was ‘driving from Bristol to Brum and watching him fall asleep on the M5 with me desperately trying to keep him awake.’

The band and crew consumed ever-more substantial amounts of drugs. ‘There were people following us around in Germany providing us with amphetamines,’ Yaron Levy, the monitor engineer, recalls. ‘There was one time – I think it was in Cologne Luxor – we’d had some crystal meth. It was cut into the amphetamine.’ The ensuing paranoia and hallucinations were so strong that ‘before the end of the show, Craig was already in the dressing room because he couldn’t handle it,’ Levy explains. ‘We were surrounded by so much smoke, I just left my desk and walked off as well and joined him.’

Even among the bigger crowds the Sisters were attracting, the God Squad, a grouping of hard core fans, maintained their place front and centre, and on the guest list. ‘The Sisters were a friendly lot, all of them,’ says Jez D’Netto, who had followed the band since 1982. ‘Despite Eldritch giving out this persona, he was a nice guy. When we were there at sound-checks, he’d always come over and ask, “How are you doing? You alright?” He wasn’t massively sociable but he would put in an effort for people who were making an effort to see the band.’

When D’Netto was waiting at Stoke railway station after the Hanley gig, the Flying Turd pulled up and he was invited in by Eldritch, who informed him: ‘You can’t be walking around Stoke at this time of night.’ D’Netto ended up sharing a room with Eldritch. ‘I was pretty off it and so was he. I remember him talking about how the quality of amphetamines had really gone downhill and about one of the Hell’s Angels at Nottingham Rock City offering him a line on a flick knife.’

‘I had to go to bed because I had work, so I asked him the time. Up to that point he’d been talking normally, but then [D’Netto adopts a slow, deep, posh voice] he said: “If I wanted to know the time, I’d have a watch and then I’d just worry about what the time was.”’

As good as a lot of the gigs were, it was clear that being on stage was not some transcendental experience for Eldritch. Others might have that experience ‘because basically they’re bombed out of their boxes,’ he once noted, but ‘I never step out of the confines of realising where I am and what I’m doing.’ Partly this was his inherent desire for control, partly it was nerves and but it was also because ‘I’m aware that the littlest thing one does, it means something, someone’s going to take it away and read something into every little action, which is why we take care about every little detail. I feel a great sense of responsibility.’

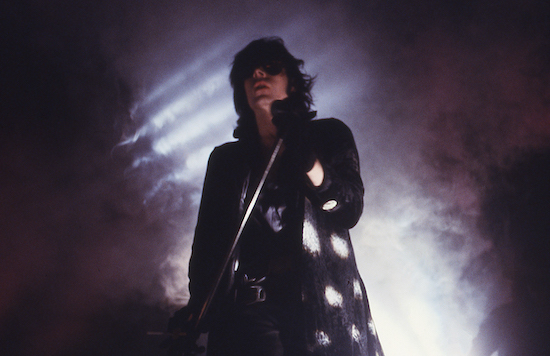

How he interacted with the lighting design was part of this for Eldritch. He had long ago mastered slinking around bare stages, but, with Wiffin, he refined the use of himself within the mise en scène. ‘Andrew needed the bigger canvas as a performer,’ Marx says. ‘It wasn’t an ego thing, it was just the things he was trying to do required it to look and sound a particular way. I think even early on he imagined a certain gesture he’d make with his arm breaking the light in an Expressionist way… fine cinematic details.’

On Black October, the band were carrying their own lights, so Wiffin was able to push the theatrical lighting and use of smoke even further. With a big rig in the larger venues, with the smoke machines on full blast, the Sisters put on a rock show that was rooted in the high contrast lighting of film noir just as much as it was in rock’s own psychedelic heritage. Not only did it look great from the audience, it photographed brilliantly. Without TV appearances, the photographs that appeared in the music press were a key element of the Sisters’ image-making and Eldritch’s own personal mystique.

Their debut gig in the Refectory of Leeds University was an especially big deal to Marx, Eldritch and Adams who had seen an array of famous bands there: the Clash, the Ramones, the Cramps among them. At the climax, during ‘Sister Ray’, Marx scaled the PA stack, clambered up to the balcony to where Kathryn Wood, his girlfriend and his best friend Graeme Haddlesey were standing and handed his snakeskin-patterned guitar to Haddlesey. ‘I think I just shouted “A” to him by way of musical instruction, or quite possibly, “fuckin’ A”, a reference to a catchphrase he’d know from The Deer Hunter.’ Haddlesey thereby became the only guitarist to guest with the four-piece Sisters. Eldritch seemed to especially enjoy this particular piece of theatre.

Although it had made him unwell, Eldritch fundamentally found being in the Sisters of Mercy deeply fulfilling. He had gone on Black October in an upbeat frame of mind. He told Sounds:

If you want it to, being involved with music will enable you to use a very great deal of yourself; I mean, I could be doing a lot of other things, but I chose, a long time ago, to do this, because it looked like I could be a politician, an artist, a musician, a lyricist, a prat, be hated, be liked, die young… There’s a lot of space there in which one can work. I’ve walked around for an awful number of years now, thinking I was God’s gift to something, whatever it was, so I don’t mind sitting here acting like some sort of ludicrous prophet. I figure that’s my natural role, absurd though it is. I mean, I don’t even go to the corner shop without figuring, ‘Hey! Here goes Andy Eldritch to the corner shop.’ This is, you know, some kind of a big deal to someone.

Eldritch was smart enough to realise that this was all at risk. The patience and cheque-book of the Sisters’ record label, Warner Music UK, were not limitless. The Sisters could easily find themselves back toiling in the fields of independent music. As the Sisters knew, life outside the major labels was hard graft with perilously fine margins. They had existed in that thin air for more than three years.

The Sisters’ schedule for next six months was therefore shockingly clear: finish the album and then go on tour again in early 1985 – an even longer one than Black October – in Europe, and then the USA, to support the album’s release. In short, do whatever was necessary not to be dropped by Warner. Debilitating drug habits, intra-band squabbles, lack of a hit single, a large hole in the album budget (and in the label’s release schedule) were all forgivable if the album hit. If it didn’t, the band would be set firmly on the path to minor cult status and, what Eldritch termed, ‘the chapeau shop’ – Spinal Tap shorthand for a real job.

Eldritch was quite sure he didn’t like the hours.

Paint My Name In Black And Gold is published by Unbound and is on sale now