In the musty dark of a Manchester flash fiction slam, there’s a bit of a commotion. One person keeps winning – and by quite a margin. He recites from memory. He wears hats. He’s annoyingly good. Wearing pained looks, his competitors – also pretty talented themselves – roll their eyes despairingly as they get drawn against him.

And then Simon Sylvester calmly, politely, and in the nicest possible way, proceeds to wipe the floor with them.

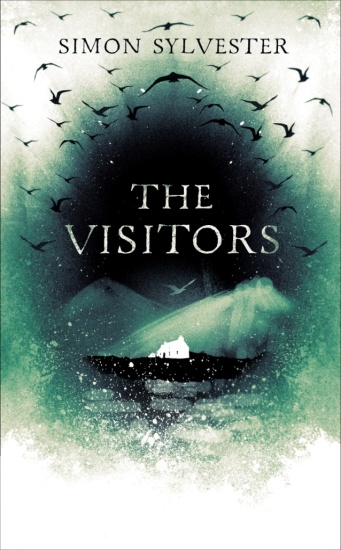

There’s little resentment. It would be hard to resent Simon Sylvester, an affable thirty-four year old who seems almost apologetic that his first novel won the prestigious 2014 Guardian Not the Booker prize. Besides being an edgy supernatural “whatdunnit” about mysterious disappearances on a remote Scottish island, The Visitors is also a meditation on myth, storytelling, growing up, the misery of love, and the act of writing itself – weaving folklore tales about the siren-like “selkies” (seal-people) that ensnare human souls with a nuanced Bildungsroman.

But his is no accidental success. Having paid his dues on the underground literary circuit for almost a decade, Sylvester currently juggles novels, film-making, photography, flash fiction and poetry (he plans to publish another collection this year) with a job and a young child – to the point where you almost wonder, unlike most writers, if he should spend a bit more time gazing blankly out of the window. Ignore the clubbable demeanour for a moment and look to the book not the man, and we glimpse a richly dark psychological landscape mapped out among the islands, dotted with myth and savagery. We talk to Simon to find out if still waters run deep…

The Visitors is written from the perspective of an adolescent girl. Was that a challenge? Why do you feel drawn to writing this kind of character?

Simon Sylvester: I had something of an epiphany a few years ago. I’d written a long, dark, and experimental novel about dementia, which people generally admired but felt was unpublishable. I completely agreed. When I came to write my next novel, I just kind of wanted to write a story, rather than tilt at high literature. As soon as I started thinking about The Visitors, I knew Flora was the one to tell it. It was her story. But writing in a different voice took me out of myself. Flora took me on an adventure I couldn’t have taken by myself, and she did things I didn’t expect. People ask me about writing a teenage girl as though teenage girls were a different species, when everyone on Earth experiences frustration, hatred, love, humour, jealousy, melancholy. We share emotions and motivations, though our circumstances are changing all the time. Writers have to be empathetic with their characters. Stories are empathy engines.

You’ve been something of a nomad since your birth. Do you think that’s fuelled your obsession with place, homeland, belonging?

SS: I’m an army brat. I spent my first eleven years in a succession of army schools and boarding schools, Germany, Scotland, England, Northern Ireland. Even now, I don’t feel like I come from anywhere. I wish I did. I’m jealous of people that have a home town. I don’t like football, but I’m envious of the tribalism of having a football team. I think people are shaped by the place and draw their stories from it.

I’m also fascinated with local legends and myths particular to place. Whenever I go somewhere new, I look for the folklore of the area – devil’s bridges, haunted houses, standing stones, witches’ woods… More and more I’m obsessed with the idea of thresholds, spaces that combine two places at once. That was what brought me to write about selkies. They are thresholds in themselves, both seal and person, but they are also defined by the balance of land and sea, doomed to live in both and neither…

Yes – and like yourself, they’re subconsciously on the hunt for a home.

SS: That rootlessness is sort of what propels the characters. Although as we see with the heroine, home can be a prison too. It can trap you. And you can lose the haven you once thought it offered.

You’re also a filmmaker. Landscape is very much a character in the book; how do you think visuals and place affects your writing?

SS: When I write, I often catch myself thinking in cameras – composing scenes as though I was composing a shot. When I set up to shoot, I think about light, about sound, about space, and those considerations now carry into my writing too – and how I shape a scene. The biggest impact of my film work on my writing has occurred in the editing. Film editing is a deceptively massive act. With a few clicks, you move entire scenes, you delete locations, you alter meaning, you rearrange and shuffle… It is incredibly simple and organic to do. Too easy sometimes. A story can be easily broken.

Your website tells us that you’ve written over a thousand “very short stories” on Twitter. Do you prefer long or short form narrative? And how does each shape you as a writer?

SS: Flash fiction is a quick hit. Novels are a slow burn. When you have no space at all, then you truly learn the value of adjectives, of adverbs… After so many Twitter stories I feel like moving on, but they taught me to distil the essence of a story into a sentence or two. But then, all that said, I love the immersion of a novel. Even when it’s a struggle – and those first 30 or 40,000 words are rough, any writer will tell you that – it’s where I like to be… Doing all I can to drown myself.

The Guardian’s Not The Booker is a prestigious trophy for a new author. Were you surprised and how did it feel?

SS: I was astonished. I was acutely conscious that genre works seldom reach the pages of The Guardian, and I feared a mauling, especially after Sam Jordison had voiced some criticisms. The whole process was bruising. Then I get the news… Having the majority of judges vote for The Visitors was a huge thrill, after the public vote was tied. It’s a peculiar thing, to have my stories read by strangers. I spent so long tucked away with Flora and the selkies that it still feels weirdly excruciating to share that with the world outside. My head and heart are turned inside-out onto those pages. Now they’re out there, and I can’t change them anymore.

Your stories have flown the nest.

SS: Yeah. (Laughs). Like selkies cast adrift in the world. Stories have a habit of wandering off.

The book is full of the rhythms of Hebridean life, though it never sentimentalises such remoteness.

SS: There’s something special about the Western isles. It’s in the light, it’s in the air. Deserted beaches and abandoned crofts, blackened timbers in the sand, the sun dipping low on the Atlantic. Squirrels in the trees, seals in the water, otters on the shore. The way the shoreline sways with kelp. The woodsmoke. The sea. When I’m there, I believe every seashell holds a story.

After my dad left the army, I grew up in Inverness. I could see Ben Wyvis from my bedroom window. We walked the dogs in the plantations above Culloden, or on the shingle at Fort George. After I’d left home, my friends lived in Edinburgh and Aberdeen – I spent hundreds of hours on trains, head slumped against the window, listening to minidiscs and staring out at Scotland. The curse of not really coming from anywhere… You end up feeling like a tourist in the country you grew up in.

Is there any irony in a happily married young father writing a novel about the destructive pain of unrequited love? How much of the novel’s savage emotion was written from experience?

SS: Ha! No one’s asked me this before! I suppose there is, yes. How can I put it…I am happily married, but that means I have more to lose. When I write about love, and loss, I’m writing about my wife, my daughter. Life is fragile. I’m terrified to watch my daughter explore this world, even as I know I have to let her do it. That love, that terror, cuts through us all. I no longer read or write to measure the depths of misery or insanity, as I did when I was younger. Selkies are fundamentally about loss. I never discovered a selkie story with a happy-ever-after.

Family, writing, jobs – was it a challenge to find time to write?

SS: This is my biggest and constant struggle. I work three days a week as a teacher at the local college and I take on whatever film jobs I can find, too. I barely ever dream. Or rather, I barely remember my dreams. Writing is how I shape and interpret and decode my world, and I’m not right when I’m not writing. When I’m in the flow and pulse of a story, and writing 4,000, 5,000, 6,000 words a day… I know that not all writers love writing, or at least they say they don’t. I do. I get drunk on it.

The book plays with the idea that writing kills the power of oral narrative. How far do you agree with that idea? Is that partly why you’re fond of live performance?

SS: I think storytelling is fundamental to human experience, perhaps one of the oldest things we share together. A cave, a campfire, charcoal on the wall – it echoes all the way back to the beginnings of culture, the first recording of human history. So I think the distinction between oral and written narrative is probably a false one. Whether it’s spoken or written, they’re simply different ways of saying the same thing… Reading is an act of sharing too, and maybe sometimes we forget that.

But writing is a solitary process. It’s bloody lonely sometimes! And live performance makes it communal. I’ve believed for a long time that writing depends on community, and nowhere is that better affirmed than at live events, storytellings, readings, slams, spoken word nights… The hunger for stories, the sharing of worlds, is a reminder of why we do this. That’s what it’s all about, in the end, above and beyond worrying about book sales and reviews and prizes. It’s about sharing worlds. Putting more charcoal on the wall.

The Visitors is due out in paperback this February, published by Quercus