From the pages of Rolling Stone and Creem in the Seventies, passing through the Newstatesman and The Observer, a cutting-edge and prolific critique has always characterised the work of Simon Frith. Tovey Professor in Edinburgh University’s Music Department, he has chaired the Mercury Music Prize judging panel since 1992. The British socio-musicologist has a multi-faceted background, which has distinguished his career both as an academic and a popular critic: with an undergraduate degree in philosophy, politics and economics from Oxford University and a masters and phD in sociology from University of California, Frith was a founding editor of the journal Popular Music – the field he has been committed to since the very beginning of his work.

Engaged with the analysis of what is usually felt rather than explained, Frith’s articles, reviews and books have been published extensively. Through academic methodologies and in depth-research, he has been interested in analysing not just popular music itself but the way people relate to it.

The starting point of our conversation has been Frith’s latest publication on live music in Great Britain from the fifties until now. Volume I: 1950-1967: from Dance Hall to the 100 Club has been published by Ashgate in March 2013, whilst the other two volumes will be on the market next year and in 2016.

Live here stands for cultural value; live music is not just the mere contingency of a gig, but also a synonym for leisure, as Frith says, night-time economy, and last but not least, a site-specific locus.

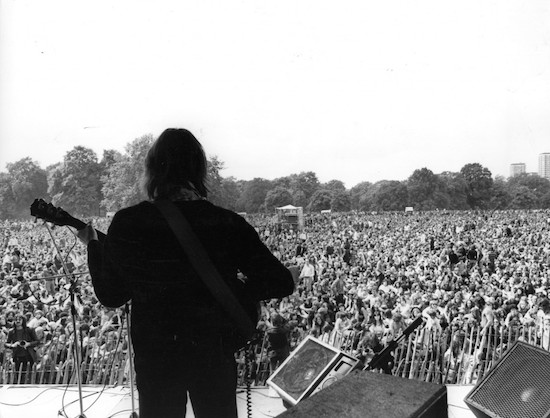

Together with Martin Cloonan, Emma Webster and Matthew Brennan, who are the book’s co-authors, Frith has focused on live music’s venues and their changes, from the state-run art centres to Glastonbury. The History of Live Music in Britain is a social and historic excursus tracing the sometimes-complex dynamics between the live business, the record industry, and the role of music promoter. It conveys the meaning of music as a cultural value, both economically and socially.

One of the aims of History of Live Music in Britain is to describe what the relations have been between the music business and public congregational places from the Fifties until now. Which idea or circumstance gave birth to the book?

Simon Frith: The live music book came from an increasing realisation that popular music studies (and social histories) tended to take for granted that the post-war music industry meant ‘the record industry’. By the end of the Twentieth Century this view was being challenged by technological change (digitalisation meant a ‘crisis’ for record companies at a time when a global live music business, Live Nation, was being constructed) but also meant ignoring the realities of musicians’ lives (most musicians make more money from live performance than from the royalties from record sales). In 2003 Martin Cloonan and I were involved in a project ‘mapping’ the Scottish music industry and it was our findings here – suggesting that Scotland’s live music sector was much more economically significant than its recording sector – which led us to develop a project looking at the history of post-war music in Britain from the perspective of live music promoters rather than record companies.

Live music deals with a certain contingency, casualty, empathy, immediate perception of like or dislike, unexpected elements, and a sort of congregational feeling too. What about

recorded music? I’m wondering if the latter could be called a mediated experience, which is an experience without a doubt, but, if compared with the live one, perhaps more reflective. Which kind of relationship with the outside world does it imply?

SF: There is a paradox here. I don’t doubt that the musical experience is essentially live. Every year I ask my first year students to describe the most intense musical experience they’ve ever had. They almost all describe a live event in which they were performing, dancing or listening; a record is rarely mentioned. They are too agreed that someone who claimed to be a fan of an act (who collected the act’s records) but who had no desire to see them live, would not really be a fan. (The opposite position—loving a band live but not buying their records—is not seen as such an odd stance.) In most musical cultures live performance defines the setting for the expression of musical values; obviously so in improvised forms like jazz or communitarian forms like folk and rock, but also in classical music (in which the ‘concert hall experience’ was the driver of recording technology). But there’s also no doubt that pop music is most enjoyed on record or that for most of us it is on records that we obsess and with which we identify.

Pop music (pop records) were an aspect of the development of radio culture, which used records as the basis of a new kind of collective listening, just as many of the most significant studio-created ‘impossible to play live’ records have been used by deejays, in clubs and discos, for a new form of public entertainment. And the most obsessive record buyers and record collectors create their own communities (which are, in turn, a key source of conversational criticism). It’s worth remembering, for example, that the first jazz clubs in Britain (and elsewhere in Europe) were places where people gathered to listen to and discuss records, which they regarded as much more challenging than anything they could hear at that time live in the British dance hall.

Your work combines music and academia, instinct and footnotes, emotions and criticism. Rock music analysed on an academic level is the proof not only of culture’s hybrid nature, but also of feelings as paradigms of identity and knowledge. Do you think there is still anybody who sees the rock-academia combination as an exotic marriage?

SF: No, probably not, though I think academics in this field (as in others) tend to think what most matters about music (as about any other art form) is its interpretation. If music is taken to

mean something — especially if that meaning is opaque, ambiguous, etc — then academics have a task in which they can become experts: the unravelling of the meaning which is somehow in the text or the performance. If music is meaningless what is there to do? Aesthetically, though, the visceral and emotional effects of music may be much more significant than what it ’means’, and these effects draw unsettling attention to the subjectivity and irrationality of taste, issues in which academics are not necessarily expert.

In Performing Rites (1998), you distinguish between critics’ considered views and conversational criticism. The former is associated with in depth analysis, while the latter is what is likely to happen in a pub conversation. At the bar people usually raise their points of view not as attentively and formally as they would do in a university class. However, a vast portion of music fans form and develop their musical tastes while chatting in pubs.

In your work the word value appears many times in different contexts. What do you think the value of conversational criticism is?

SF: For fans (of all music) the value of conversational criticism is obvious. It is essential to the creation of musical communities — which are, in essence, discursive communities. It is the setting in which opinions are shaped, critical terms refined, evidence tested. The question is whether critics should be or are fans of this kind. In popular culture the answer is probably yes. For instance, blogging has had an interesting effect on critical conversation. The best rock criticism nowadays is written in blog form but by established critics. Bloggers like Simon Reynolds and Richard Williams, for example, are as authoritative (and have as strong a sense of critical tradition) now as when they were writing exclusive for newspapers and magazines, but their readers can now make a direct, individual and often immediate response, which is usually framed not as a ‘reply’ but as a way of moving the conversation on.

Once you said that ‘the critic’s task is not to denounce music in the marketplace (where else can music be?) but to make market choices matter’. This viewpoint implies a sort of holistic conception of society, which encapsulates and eventually metabolises also what apparently stands against it, such as protests and demonstrations of any kind. As a matter of fact, music exists within the market, and when it doesn’t, it is actually difficult to even notice it.

The entire population is involved in (mass) consumption, and to pretend not to be part of it means to place oneself in an unrealistic other world. If this is true, where are music of protest and the do-it-yourself music exactly placed at the present time?

SF: I wouldn’t argue this in quite the same way now because I now think music has to be understood, in economic terms, as a service rather than as a commodity. Music is certainly in the market place, but the trade is in musical services (which might include recordings) rather than musical goods. From this perspective, the ‘mass consumption’ of music involves not only global corporations but also a great number of local, non-commercial, interactive and irrational exchanges. One finding of our live music research was the importance of the ‘enthusiast’ promoter, who puts on concerts out of love of the music rather than as an economic enterprise. That said, the sustenance of the musical economy needs a core of profit driven investment and for a musician or their work to have any sort of public impact it certainly needs a well-developed marketing apparatus. Social media have offered new opportunities here but not changed the underlying economic model. People have always made music for themselves and always will; the question is who else will hear what they do. The problem of the old do-it-yourself indie model of music making was not that people did it themselves but that they wanted to do it for as many other people as possible. The logic of success, that is, still involved a belief in growth, increased sales, etc. This applied to protest music as much as to anything else. Co-option was and is always a bigger threat than censorship.

Your work has always been driven by a sociological interest, lexicon and way of seeing; your interpretation of the music status lives in a liminal field in between sociology, philosophy and material culture. Not to mention that your practice is placed at the obvious intersection of music and writing. Sociology of Rock (1978), with its very title, gives a clear example of the interaction between various fields of knowledge.

This eclectic composition adds value to your methodology, it is a resource, and it facilitates a collective comprehension. Last but not least, it is a powerful reaction against the academic pigeonhole, which usually tends to favour a radical purism of disciplines.

Your biography depicts you as a politically engaged man and professor; could you tell me something about the relationship between music and politics in your life and work?

SF: I started out as Marxist and continue to believe that culture has to be approached through an understanding of the means and relations of production and with a close attention to ideology and discourse. For me, all academic study involves politics and an interest in the details of power (whether in the recording studio or the stadium). My approach here was also no doubt affected by my own conditions of production, my own socio-historical circumstance. Rock music, for example, with which I was centrally engaged as fan, journalist and academic, had its own political conditions and assumptions with which I had to engage.

But my politics had less to do with particular stances than with thinking about what ‘engagement’, as fan, journalist and academic, meant. I was always concerned, for example with music policy, with the ways in which the academic concern for method and evidence could have a practical effect. This has meant, perhaps ironically, that I have always been more interested in understanding (than denouncing) the music industry, while also seeing the academic role as representing citizen rather than industry interest (in arguments about copyright, for example). Music has been, in a sense, the embodiment of my political ideology: practical utopianism.

The History of Live Music in Britain, Volume I: 1950-1967 is out now, published by Ashgate. Volumes two and three are forthcoming