Had it not been for John Silva, his partner at their management company Gold Mountain Entertainment, Danny Goldbergmight have never managed a relatively-unknown alternative rock trio from Aberdeen, Washington, called Nirvana. It was around 1990, and Silva suggested to Goldberg to consider bringing on Nirvana as a client. But Goldberg was reluctant to take on younger and unproven acts (Gold Mountain’s roster had included established acts such as Bonnie Raitt and Belinda Carlisle). Undaunted, Silva asked another client of Gold Mountain, Sonic Youth co-founder Thurston Moore, to reach out to Goldberg and advocate for Nirvana and its charismatic frontman Kurt Cobain.

“It was immediately clear when we started working with Sonic Youth how Thurston and Kim [Gordon] were brilliant not just as people,” Goldberg recalls years later, “but they truly had their fingers on the pulse. Thurston said, ‘Look, I know you don’t like new acts, but you might want to make an exception. [Nirvana] is the best band I’ve seen in a while.” And that’s all I needed. We met the band, and I think they felt the same way about us because of Thurston’s and Kim’s confidence that we could manage Sonic Youth, and they liked us. It was an instant credibility in both directions. So they committed to us at the first meeting and we committed to them at the first meeting.”

And as the cliche goes, the rest is history: for the next four years, Danny Goldberg guided Nirvana and witnessed the highs and lows of the band’s phenomenal success as a member of the inner circle. Twenty-five years later, on the eve of Cobain’s suicide on April 5, 1994, Goldberg chronicles that incredible period in his new book Serving The Servant: Remembering Kurt Cobain.

While the overall details will be familiar to Nirvana’s fans, Serving The Servant offers an insider’s perspective of the group’s story, touching on such things as the grassroots work on the part of DGC, Nirvana’s label, to promote the band; the crucial relationship between the band and MTV; and how Cobain was heavily involved in not only the creative aspects of Nirvana’s music but also the band’s business and marketing affairs.

Other interesting highlights from the book include Cobain’s relationship with Courtney Love; his pro-feminist and pro-gay views that contrasted with rock’s traditional misogynistic and homophobic culture; his rivalry with Axl Rose of Guns ‘N Roses; and the fallout and personal strain caused by an infamous Vanity Fair article article from 1992. While it doesn’t sanitise Cobain’s story, Serving The Servant portrays the singer more as a person than a tortured rock star.

A well-known figure in the music industry for many years, Goldberg was vice president at Led Zeppelin’s label Swan Song, and then later served as chairman and CEO of Warner Bros., the Mercury Records Group, and Artemis Records. Now president of Gold Village Entertainment, Goldberg has penned the books How The Left Lost Teen Spirit, Bumping Into Geniuses: My Life Inside The Rock and Roll Business, and most recently In Search of The Lost Chord: 1967 and The Hippie Idea.

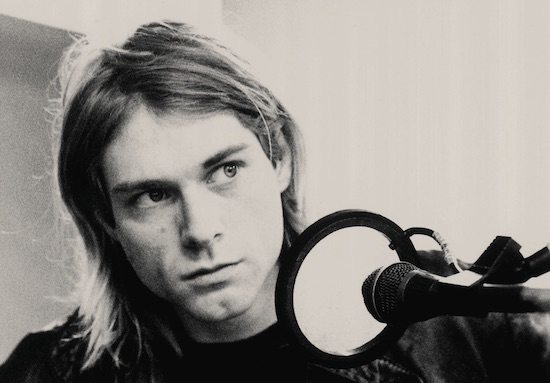

Photo credit: Jeff Kravitz

In this exclusive interview with The Quietus, Goldberg looks back at Cobain the genius; the moment when he truly realised how special Nirvana was; and the moment during which he painfully confronted Cobain to get clean, shortly before the singer’s suicide.

Why did you wanted to write a book about your time with Kurt and Nirvana after all these years?

Ever since Kurt died, I don’t think a week goes by that somebody doesn’t ask me about him. He’s a remarkable figure in the history of rock and roll. He’s never gone out of my mind. And I felt for some time that there was a side of him that hadn’t quite been rendered. The tragedy of his death was so awful. And that before he died, he had heroin problems, he was prone to depression, and things like that. All of those things are true, but they’re not the whole truth. His brilliance and sweetness – I just felt it was missing from the public record of his life. So it was In my mind someday I might want to do it.

Was working Serving The Servant in some ways cathartic for you, given the special relationship you had with Kurt?

A little more than I realised it was going to be when I embarked on it, because it was reliving a very important time in my life. I was stunned sometimes about how much was happening in short periods of time. It allowed me to express things that I felt but hadn’t written out. It also reconnected me with dozens of people who I spoke to. I have stayed in touch with [Krist Novoselic, Nirvana’s former bassist] over the years. We share a lot of political views and end up being at the same meetings or events from time to time. But we’ve never talked about Kurt, and that was true with a lot of the people I spoke to [for the book], even those who’ve I been in touch with and those I hadn’t been in touch with since the ‘90s.

Your introduction to Nirvana happened first through your colleague John Silva at Gold Mountain Entertainment, and then later through Thurston Moore.

At that time I had a bigger company and I needed somebody younger [like John] who felt the pulse of this next wave of alternative rock that I knew was coming up. So we signed Sonic Youth the year before, which was a big get. That branded us as being meaningful in that [indie] subculture. There was at least one or two occasions in which John suggested acts who were very critically acclaimed or admired in the subculture. Running a management business, you have to pay your monthly bills, the money has to come from somewhere. So I was always skittish and cautious about newer artists – not that I didn’t like the romance of discovering or advocating somebody early in their career, but that it was hard to make the mechanics of a business work with them.

What was your first impression on meeting the members of Nirvana?

I got the feeling that they were very unpretentious and earnest and committed to what they were doing. Initially in the meeting, in the first 15-20 minutes, Krist almost did all of the talking. As I say this in the book, I was trying to get a feeling for what they wanted to do regarding record labels because they were on Sub Pop at the time. There were a lot of artists in the indie world that felt that going to a major label was selling out in some way, and I didn’t want to be a crude old school person pushing them any direction. So I asked the question, “Do you want to stay with Sub Pop?” And before I can finish the sentence, Kurt said, “No.” He hadn’t even said a word before then in the meeting. So that told me two things: they wanted to be on a major, and that Kurt was the boss.

It was only a couple of months later that I actually saw them perform live. They were playing the Palace opening for Dinosaur Jr — I think it was before they recorded Nevermind. We already made the deal very quickly with DGC. I remember I went by myself and stood in the back. I was just mesmerised, or transfixed is a better word, by Kurt. He had this intensity and an emotional connection with the audience that was really unique. I had seen hundreds and hundreds of shows. I was pretty jaded by this time about the business, and I fell in love as a fan, and I didn’t even know that part of me was still alive.

That was really when I changed my focus on the band, after I saw them at the [Hollywood Palladium]. They went from being something that John was working on, to something that I was going to be involved with as well. I didn’t know how big they were going to be, but I knew they were going to be important artists.

You and Kurt were from two different generations and cultures: you worked primarily with the traditional major labels, and he came from an indie rock background. Why do you think the two of you meshed well?

Courtney said to me when I was doing the book that the fact I was associated with the American Civil Liberties Union was a plus in their eyes. It was an avocation of mine that meant a lot to me I think that differentiated me in part maybe from typical music business people. Part of it was that I was smart enough to have John near so he really understood the granular details of the culture they emerged from, the fanzines, the indie stores, the local clubs. But I think a lot of it was just an intuitive connection between two human beings. Part of it is a happy mystery. There were some unhappy mysteries when it comes to Kurt, but that was a happy one.

The common refrain in the book is that Kurt was a planner. He knew exactly what he wanted to do in shaping Nirvana’s music and image.

He was incredibly smart. He had absorbed – with an extraordinary amount of sophistication – what rock and roll was, not only as music but also in terms of its relationship to the business world, its relationship to the culture, and the media part of it. He had an extremely sophisticated idea of what he wanted to do, and he did what he wanted to do. It didn’t make him completely happy. But it was something that he was driven to do. I sort of intuitively felt that from the moment I met him, and every decision that was made was in that context. Krist, who knew him a lot earlier than I did, absolutely felt that and said the same thing.

If you look at Kurt’s journals, it’s quite clear that at an early age he was envisioning success. He was thinking about the band in relationship to all these different other cultures, dominantly influenced and inspired by the the American punk rock of the ‘80s. But [he] also loved bands like the Beatles, ABBA, Cheap Trick, and Black Sabbath. Somehow in his mind, [he] was able to conceive of an iteration of rock and roll that would include all of those things in some seamless way that would also have this intimate connection with young people about what it was to feel like an outsider. It was an extremely complicated undertaking that no one had done before.

He was much more disciplined than some of the cartoon images of him would indicate to anyone. He was obsessed with practicing – enormous amount of rehearsal was part of his code from the beginning. He was a craftsman at songwriting. And he had a precise attitude about every single decision, whether what colour his hair should be for a particular photo, or what the artwork was going to be on a single sleeve. He was 24/7 committed to becoming the public person that he became.

The book kind of sets the record straight about Kurt’s relationship with Courtney Love, who has been perceived in some quarters as an opportunist who arrived in Kurt’s life just as the band’s star was rising.

Courtney would be the first to admit that she is intensely ambitious. As she said to me, that was one of the things Kurt liked about her. There was no question that he was in love with her. That was something that he told me right away. And I liked her personally – I still like her. It was a love story. I think they had their problems that created some weird times. There’s no question that both had drug issues at different times. They were crazy about each other. Again, in going through the process of talking to people who were around them at that time, there was no question that was the case.

But there were people who resented her. And you add to the fact that Courtney is an extremely intense person and a woman in a man’s world, she became “controversial” in some circles. But to me, she was a person he was in love with. He made that clear to me. And I think one of the things that made us closer is that I immediately offered to manage Hole. He liked that idea a lot. I’m also an admirer of her as an artist. I think her work speaks for itself. I think she’s a terrific artist in her own right.

It is remarkable in your retelling how much Nirvana had accomplished and done in a very short period of time – things that would take other bands a lifetime to do.

It was just not an American phenomenon. To be with Nirvana in Paris or Buenos Aires, Sydney, Australia, Osaka, Berlin or Rome was the same dynamic happening in Seattle and New York. He touched a chord globally. I think it blew his mind. But he was proud of it, too.

There’s a home video that came out [Nirvana: Live! Tonight! Sold Out!!] that he really edited. Kevin Kerslake was the director and he deserves credit for finishing it, but Kurt spent hours and hours in his apartment editing it and piecing it together bits and pieces of films to show the global nature of that exact thing that I was describing.

Again what he did, he did on purpose. It didn’t make him happy some of the time, but he had a vision that he executed with an extraordinary amount of sophistication. He continues to represent a certain integrity, authenticity, compassion and soulfulness to people who weren’t even alive when he died. He’s not the only artist who’s done that – it’s true of Bob Marley, Jimi Hendrix. It’s a short list, though, and he’s on it.

One of the heartbreaking moments from Serving The Servant is when you confronted Kurt to get help for his drug addiction. This happened shortly before his death.

It wasn’t the first time we talked about this. I didn’t want to be a nag, but he knew how I felt about heroin. We had done an intervention a couple of years earlier on him and Courtney in the beginning of 1992 right after they did Saturday Night Live for the first time. And in the intervening time, he knew I was anti-drug, so to speak. He also knew that I loved him.

I wasn’t trying to judge or condemn him, I was just worried about him. I felt a sense of despair and impotence in that last meeting. He did eventually go into rehab but he only stayed there like a day or two, and then he left and killed himself. I felt terrible about it and I didn’t know what else to say and do. I asked myself hundreds of times in the intervening years if there was something I could’ve done and said at that time. I’ll never know. I only know what I did say and do.

As a music industry veteran for so many years, you have worked with a who’s who in the business, including Led Zeppelin, Stevie Nicks, the Pretenders, Warren Zevon, Rickie Lee Jones, Peaches and Steve Earle. For you, how does Kurt fit in?

Kurt’s on a peak all of his own in my experience. He was so good at so many different things. In history there have been people like Bob Dylan, John Lennon, Bob Marley, Bowie – he’s not the only [one]. He is the only person in that limited pantheon I was that close to. I have long known that if anyone writes my obituary, it’s going to be ‘Ex-Nirvana Manager Danny Goldberg.’ There is nothing I can ever do that would be as important to the rest of the world. So in that sense, he’s number one.

On this 25th anniversary of Kurt’s passing, what do you wish people will take away from the your book?

It’s a mosaic of a hundred pieces. There are certain things where I express my opinions about how certain decisions were made that were different in some other depictions. The main thing I hope is that it reconnects people with his genius. For example, when I think about Jimi Hendrix, I think about his music. I don’t think about how he died. And I would hope that’s more and more how people will think about Kurt – not his death, but his life. In 27 years, he gave the world a lot. I still think it’s very meaningful. I wished he lived longer, but I’m really glad that he lived.

Serving The Servant: Remembering Kurt Cobain by Danny Goldberg is published by Trapeze