1: ‘…there was a sunlit absence.’

One of the last things I did before leaving home was go up North to see my friend Chris Kitson. Heaney Country. The hill where they hunted Henry Joy McCracken down. Broad, pale-grey spits tapering out to a gentle gleam of nowhere. The Wishing Chair at Giant’s Causeway. Cows, fields, etc.

We played a game. I Spy, only about things we could still do poems about. I said Plough. Chris said No. I said Keenan EasiFeeder. Chris said Boring. Chris said Bat. We debated Bat. Heaney quotes the James Joyce line about bats in one poem. James Joyce cogged it off of Aristotle. It would be a big theft.

Nearby, a bat thunked to earth in a brief flash of gold. Another Nobel medal lasso!

The man, Chris said, has staked his claim to anything even remotely good about being from here.

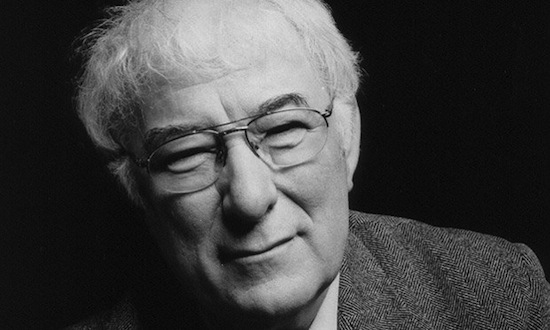

Me and Chris and Seamus Heaney go way back. We bonded over him with Goldschlager and Communist paraphernalia in our college’s sterile efficiency flats. He was our sustenance amid the aridity of critical theory and academic philosophy. Talismanic, carried with us like Pascal’s necklace or Leo Bloom’s spud. We had our pristine Fabers and the nubbled covers you’d run your fingers over, just to feel them in the whorls. If they could grate a note it’d be full, strummed, textured: his.

Sometimes we felt like he was a promontory lighthouse blocking the view. Sometimes we wished he’d just stop, retire, the stuff was so overwhelmingly good. Now that he has died in to his work I wish I could take that wish back, swap all those moments for moments when I’d just enjoy the light he cast.

He wasn’t a poet. He was a landscape, an entire music. The deep vowels in hoke and thole, all that lower-octave stuff: that was so much his we used it as a tuning-fork. We hunted our vocabulary for sounds not his. Then we’d give up, and just enjoy the show.

That day we stopped at a bay of drumlins: low islands left in water by glacier melt. The number of drumlins in the bay varies depending on the tides, on how many you can count through the skeins of fog.

This bay is like a shit essay on liminality, I told Chris.

Don’t tell Seamus Heaney. He’ll only steal it off Seamus Heaney, Chris said back.

Only we steal from Seamus Heaney, Chris. Everyone knows that.

The man himself rumbled away on our car-radio. A loose fan-slat hummed: sympathetic vibration. For a man who did so much to blur frontiers, his was a fearsome poetic territory. After a while we stopped being glib and chippy and just looked, and listened. Heaney Country scrolled by. Salt wind. A Lagan the colour of sake, Heaney’s voice spooling out endless and constant as the fish-scale ripple of light working off water. Smoky winter noon. Basalt sea-gates.

We couldn’t picture him gone.

2: ‘Keep your eye clear/as the bleb of the icicle.’

When I heard, I was three-quarters asleep. I stabbed out some words on my phone. Unfelt, not right: that rubber-and-circuitry separation, the identikit look of the characters on my shitty screen, the stun I was in. Lost, then, when I answered a work-text. That’s the grief-muddle for you. There and not there at once, blown open. I want to read none of it, Chris writes to me on Gchat, and at the same time I don’t want to read anything else. And, also, for us both, a niggle in the shock: I’ll never meet the guy now. Then the guilt over feeling something, at listening to the little alarm-blip of ego that always throbs away whatever the scale of your grief. Like it wants to distract you.

To stay with the grief: that’s the thing. Not to let it pass, to let it work in you like the deep strum of a kite jerking against your palms. I’ll never meet the guy now.

It feels like everyone wants to write these days. We’re tumbled out of BAs and grad programmes with the brilliant, undifferentiated shine of bagged seeds. I know you’re on your own over there, Chris writes to me on Gchat, but being around everyone here at Queen’s doesn’t make it any less lonely. And, yeah, that’s how it is in general. Knowing that the lonely-soul count is now in the millions somehow amplifies the problem. Crouched over our tiny windows, looking for worlds that haven’t yet become petrol deserts. The statements we make feel bigger than the homes most of us will ever find for them. The ground teems with our litter.

I’ll never meet the guy now. It wasn’t about networking. It wasn’t about some quest for a laying-on of hands, of the kind that makes Tobias Wolff’s Old School such a hilarious, painful read. It was deeper than that.

Seamus Heaney was a stay against loneliness. His voice held you. It was the arm at your elbow helping you step a fence. It sure, cautious goat-pace over its own line-breaks. His voice walked with you. I spent ten years chasing him. When I was in first year English we were seated in alphabetical order. ‘S’: so, down the back. S, now work. One of the days I actually did do something I finished early and flicked through our reader. Heaney’d gotten the Nobel six years earlier: he took up a whole section of the poetry bit. The Nobel seemed an endorsement. I had a look. I haven’t looked up since.

It was his early hits. ‘Digging’, ‘Follower’, ‘Requiem for the Croppies’. ‘Follower’ put a queasy clench in me over being a jerk to my Dad. Seeing that nailed down before me: it was a sentence, a conjugation, a doom. All I could do was be there with it. Stay with the hurt, work through. ‘Requiem for the Croppies’: ‘the hill blushed with our tide’. Being brought up so far South, I’d always been taught to suspect my history, to deflect thought with mild, forelock-tugging phrases. Fault on both sides, the Rah went too far, there’s peace now and sure that’s all that matters. But the hill blushed with our tide opened a window on the horror of human cancellation: again and again and again, a relentless, maniac repetition, now and then, here and everywhere. It was like seeing a new language for what people did to one another: elegant, horrified, adequate to the scale.

And then, a few minutes before the bell for class, ‘Digging’ offered me another, redeeming cancellation: the trance-state that descends when doing and being fuse. I need to meet this guy, I thought to myself.

I sat back out of reading. A plane’s hull glinted down from 30,000 feet. There was a new, cleaned feel in my head. The moment shone here. I watched the plane’s bright nib score a line across a blank page of ozone-blue. The script bloomed as it faded. I’d seen millions of planes and never thought how amazing it was that its glint could write a wire all the way down to the ground.

I’d been Heaney’d.

3: ‘Let whoever can win glory before death.’

I need to meet this guy. 17, reading deeper, and a fever of embarrassing ambition on me that wouldn’t lift for another five years. I was at my aunt’s house for the weekend, sleeping in her library. Virgil, Dante, Milton, all that scary stuff you’d read two pages of all virtuous fervour before slinging aside when it didn’t yield enough of the accustomed reading pleasure.

Another secondary school reader, one covering the year Heaney was on the Leaving Cert course. It nearly had a taste it was so good. Turning the sounds of ‘Mossbawn’ over in my mouth until they lived on my tastebuds. Lysergic films of his images played in my head like gifs. ‘Skunk’ made me wish I’d marry someone I could feel that way about after we were married.

Which is when it really started: the intense stuff. The jealousy, the vying. He knew Latin! He’d translated Baudelaire! And not the shitty, annoying, Jim-Morrison-influencing Baudelaire, either! He’d done everything: the cool bits of Dante, the bearable bits of Virgil. He’d knocked back shots with Robert Lowell and defeated Joseph Brodsky at pub-talking. If he had to, he could probably eat a yard of stew. Jesus, he’d even won the Nobel Prize while in Greece – crowned at Delos, if you like – and then had the good grace to celebrate with squid and chips and little else.

Some of it was cute. I ate Star Bars instead of Moros for ages because someone told me they’d seen him eating one in a shop once. I smoked loads of fags because he smoked loads of fags. I copied out Death of a Naturalist by hand so I’d know what it felt like to write like a Nobel Prize winner. I dreamed my pen-nib to a record-needle, followed every whorl and groove of his diction so’s it could ring deep in my language’s muscle-memory. I craved his marriage of technique and pure feel. I tried to code him in my very fingertips. He’s not just a name, Chris wrote to me on Gchat, he’s an entire syntax.

Some of it wasn’t so cute. Some of it was even worse than Old School. I spotted a man who looked like him after a reading: a big reading, Heaney’s first since the stroke. I charged over. I can’t remember what I said. I’m not him, said the man, I’m his brother, Michael.

Michael was very nice about it. We talked about farming for a bit. It was funny and he was sound, but I probably also looked like a beetroot.

Then there was the dreadful poem I sent him. I Tipp-Ex’d out the return address at the last minute. And then there were the dreadful poems I wrote in Michael O’Loughlin’s poetry class. These are good cover versions, I’d get in Michael O’Loughlin’s poetry class. Stop chasing the man, I’d get in Michael O’Loughlin’s poetry class, he’s already well gone over the horizon.

Stop chasing the man. But chase I did. Going by going, like a madwoman in a field, as Clarice Lispector says. Finding departures at every destination, like Seamus Heaney did.

I chased his paper trail, and I found a whole world: Robert Lowell’s agile thirteen-line sonnets, the Mandelstams and Elizabeth Bishop, Milosz, Herbert and Holub, Szymborska and Sylvia Plath. I dug and dug and dug at his work, dived after his ‘nugget of harmony’ so’s I could tune myself against it and finally stop playing cover-versions.

I wanted to win glory before death. I needed to meet the guy. I tried to steal from him. He gave me everything. I tried to be him. His work gave me myself. I could try for words of thanks but the sadness has already muted all speech and I don’t want to lure myself in to the Augustine trap. No: I’d far rather be deprived of my grief than – I hesitate to say this, but his work invites this intimacy, same as a father does – than be deprived of my friend.

I actually did meet him once, after a reading in college: one of Michael Longley’s. The silence dropped row by row when he stepped down through the lecture theatre. In his introduction to Beowulf, Heaney talks about how his father and his father’s friends were like the warriors in that venerable text. Scullions, he calls them. Well, here he was: a real-life scullion striding among us.

Michael Longley was back in Trinity as Professor of Poetry of Ireland. I asked him to sign a copy of his Collected Poems, talked to him about John Clare. Thankfully he didn’t remember either me or the shit poems I’d sent him, so it was actually grand. I waited for the autograph scrum around Seamus Heaney to clear. I didn’t want any laying-on of hands anymore. I didn’t want to stand out. All that was going from me by that point. I just wanted to say thanks was all. He signed my notebook, in green ink, with a Roman numeral for the year date, and I told him to keep up the good work: I’d been getting good marks for essays I’d written about him. He laughed. His hand was smooth and tough and simply there when he gripped yours. A hand you’d let help you cross a fence, sure at your elbow. His warm, gravel-rumble laugh.

I’d had no need to meet the man. He’d been there with me all along.

4: ‘The space we stood around had been emptied.’

We’re fond of libations here in Mexico. Day of the Dead is coming, so my friends will be laying their loved ones’ favourite food and drink at their gravesides. My flatmate’s going to build an altar for his father.

Today, I’m going to the Monument to the Victims of Violence. It’s a forbidding array of rust-tone slabs, quotes and pleas scraped in metal by the public and by state-sanctioned thinkers. The government left the monument’s purpose ambiguous: it may be for those who died under that hazy rubric of drug-related violence; it may also be for victims of the police. On grim days, it’s not a place you’d go to mourn: more shiver. But today it’s bright: so I’m bringing a small measure of overpriced import Jameson and some flat Guinness I got out of a dented can.

But glazed in the clarity we get for two hours a day before the smog rolls in like sea-mist, the Monument will look like Deirdre Madden’s imagined Troubles memorial from One by One in the Darkness: just the names of the gone, unroofed, light and air, open sky. A blank slate of shine. The steam from tamale-sellers will drift and fray: the cell-release of earth’s breath.

I’ll wait before I pour out the great man’s preferred tipple, wait until the smog rolls in over the volcanoes: their drumlin curves through the grey. The sky will close in and so empty space. Near the Korean Pavilion, the firs will spell their cursive out on a page of fog. I’m just sorry I can’t bring a Star Bar.

I’ll stand under a cross-hatch of palm-blades and I’ll pour out my offerings.

There will be a sunlit absence. The space we were standing around has been emptied.