If you’re in generation X, you’ll likely have already received several books at Christmas that are purported to be ‘ironic’. Things like Parker’s Cars where the esteemed chauffeur from Gerry Anderson’s Thunderbirds tells you about the “best bloomin’ motors,” or those Ladybird books which look and feel exactly like the volumes we grew up with, only have titles such as The Ladybird Guide to the Midlife Crisis and such. These books may elicit a thirty-second chuckle, but are usually consigned to the charity shop not long after the gifting period has ceased (my copy of Parker’s Cars went a while back). And then there’s the Scarfolk Annual.

At first glance, you might want to lump the Scarfolk Annual in with the above – especially as, like the Ladybird books, it’s patterned after the reading material of our youth. I bet if you gave this to the charity shop they’d shove it right in the children’s section, squeezed in-between annuals of Jackie, Eagle, and Buck Rogers in the 25th Century. And that’s immediately part of its genius.

Annuals were good and cheap stocking fillers, something to be given to the kids that was something that at least felt partially educational alongside space hoppers and Slam Bam Sam (the latter being a set of two remote control VW Beetles designed to crash into each other, although the name now sounds more like the Thursday strip act at the local social club). But the point is that they were just gifted to kids for them to read either at their leisure or, more pressingly, to leave mum and dad alone while they were peeling sprouts.

And of course, parents were not expected to be worried about what was in the pages of stories, puzzles, and jokes. No one expected Superstars to be full of subversive material. But this is where Scarfolk comes in. The first difference from the ‘ironic’ books mentioned above is that the Scarfolk Annual is an actual book, a brilliant work of satire instead of a novelty, which you’ll know if you’ve read the Scarfolk material on social media, or if you read the previous book, 2014’s Discovering Scarfolk.

Scarfolk is a small English town that is terminally stuck in the 1970s. This is where it runs free with its influences, from the television serials of Nigel Kneale and the horror of Threads to fondly remembered public information films such as Play Safe, which featured a child who accidentally threw his frisbee into the local power station and was subsequently electrocuted while trying to retrieve it.

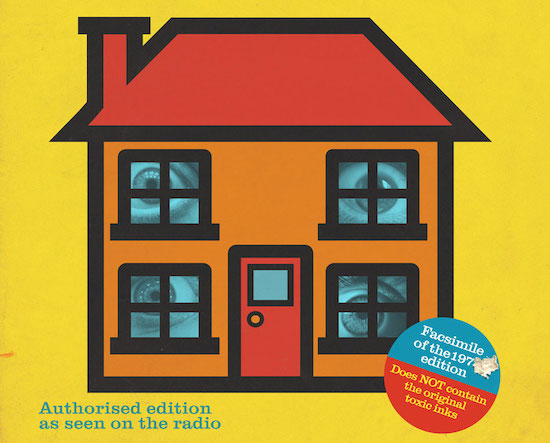

One of the brilliant things about the Scarfolk Annual – and indeed Scarfolk itself – as created by northerner Richard Littler, the self-appointed Mayor of Scarfolk, is that it wears its humour proudly on its sleeve. But at the same time, it’s so well-constructed that it will catch out those who only look at things for their face value, concentrating on certain aspects while ignoring others (which inevitably are the ones that explain what’s really going on). On the cover, the “S C A R Folk Sanctioned Books” logo is patterned after the 70s BBC TV logo, and text at the bottom states “authorised edition as seen on the radio”. Even the main cover illustration is a parody of the house from the BBC children’s show Play School, but behind the windows are eyeballs widened in terror that remind you more of A Clockwork Orange.

Littler has been doing this kind of thing for a while, here it’s just concentrated. Last year, the Government was forced to admit they made an error by including a Scarfolk poster in an official document for civil servants about historical government communications. The poster in question said, “If you suspect your child has RABIES, don’t hesitate, SHOOT.” Immediately the annual goes for this kind of effect, telling children in small print that sleep iss a man-made construct that no one else undergoes but the reader, that Father Christmas is a sham and instead parents have been slowly poisoning their children. From here there are cut out reconstructions of famous poltergeist hauntings, a logo quiz based solely on cigarette packets, and the comic strip adventures of “Waugh In War”. This last is a take on the World War 2-set strips of old Fleetway titles featuring a racist bloodthirsty General whose solution to low ammunition supplies is to leak battle plans to the enemy so they can slaughter their troops leaving fewer men to use it.

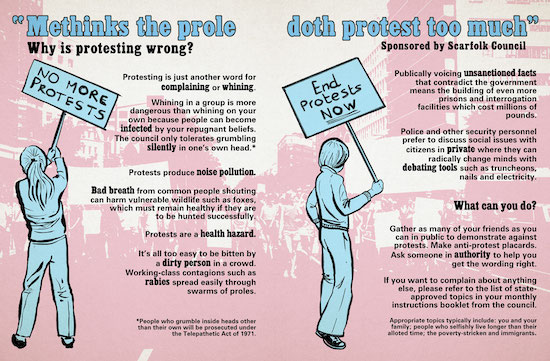

It’s thoroughly dark, dark stuff, but there’s an incredible sense of depth, especially mirroring the politics of our current decade. This is neatly summed up with “History Facts: When Britain Was Part of Europe,” which states that the Britons dug out the English channel to separate themselves, only to discover after celebrating that they were now an isolated island with very little food and no water. The tone of the book swiftly veers from straight parody to the darker, apocalyptic tinge that pervades the entirety of Scarfolk. It’s difficult to get through a few paragraphs without cracking up at something either absurd or grimly true that Littler has inserted.

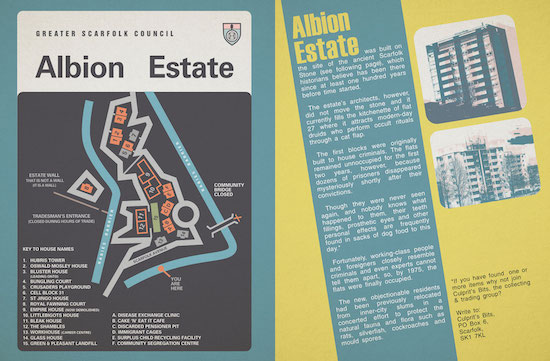

A ‘Foreword’ introduces the book as a facsimile of a found object, the original of which contained not only psychotropic inks but also blood of a terrestrial and non-terrestrial kind. Throughout the pages are bits of text in a childlike scrawl, stating things like, “Why can’t I remember who I am? None of us can,” and “I only pretend to swallow the paperclips they make us eat”. There are photos of a block of flats known as the “Scarfolk Henge Ritual Housing Estate,” with crude crosses drawn over the image with a key that states “no windows”. And then we have Barry and his doppelgängers, the leader wearing a bunny mask to disguise his horrific burns.

The Scarfolk Annual demands that you read it multiple times to decode every secret inside it. It’s beautifully built to conjure a hilarious yet sinister world built on the foundations of Britain’s genre fiction. Littler’s creation is easily able to stand beside works such as The League of Gentlemen and Garth Marenghi’s Darkplace as a unique addition to the canon of contemporary weird Britain. It doesn’t hurt that the book is also very, very funny.

The Scarfolk Annual by Richard Littler is published by William Collins