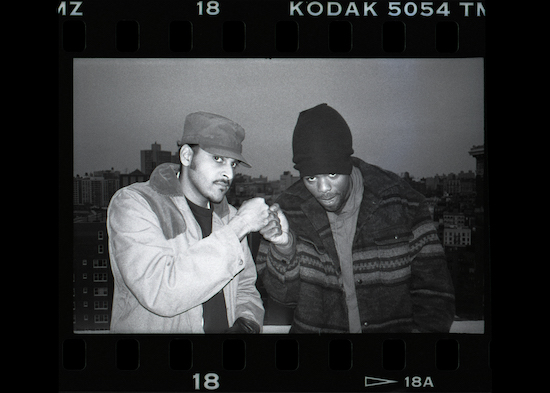

S.H. Fernando, Jr, with Method Man, November 1994 (photo: Christian Lantry via S.H. Fernando Jr.)

As a regular contributor to The Source and Vibe in hip-hop’s late golden age and the author of one of the first hip-hop histories, the 1994 book The New Beats, Brooklyn-based S.H. Fernando Jr had catalogued the career of the Wu-Tang Clan from the group’s first steps out of Staten Island.

Along the way, Skiz found himself crossing the tracks that separate journalists from artists, his fly-on-the-wall reporting of the making of a string of classic albums not only affording him unbeatable access to the group as they broke out of the rap underground and changed the way the music business worked, but also seeing him become a part of their long, strange trip. His is the voice that turns up midway through GZA’s Liquid Swords LP, playing the part of Mr Greico – a dealer trying to stiff the Clan – in a skit that, he says, was acted out with startling verité by RZA, lapels grabbed and spittle flying in a staged but unscripted and visceral encounter in a New York studio.

Fernando spent the decades since pursuing a bewildering range of creative endeavours. He ran the independent label WordSound, made a feature film, trained in (and taught) culinary arts, even launching his own brand of curry powder inspired by recipes from his Sri Lankan extended family. At one point he found himself making TV commercials to encourage Iraqis to vote in the country’s first post-Saddam election. Now living in Baltimore, he spent most of the first year of the COVID pandemic returning to the Clan and crafting his latest book, From The Streets Of Shaolin, the definitive history of the band in their imperial phase.

“It was a very hairy time to be there, right after the invasion,” he says, casting his mind back to Iraq, “but the thing that really kept me sane was listening to the Wu-Tang. It was like aural testosterone – like, keep your spirits up. Wu-Tang has always been influential and important in my life, and I feel like I’m kind of giving something back to them now by writing the book.”

What about beyond personally – were there things about the musical, social, and political climates that meant the time was right for you to write the book, too?

I think it was time to really tell that story, with the eye on the bigger picture of what America was going through. The 90s in America was a kind of comfortable time for a lot of people. Bill Clinton was president; a lot of people didn’t even think about politics because everything was going so well. But these guys who had absolutely no opportunities. To me, that’s the most amazing part of the story, how these ten kids from the projects with absolutely no chances or opportunities to improve their life just basically took it upon themselves to join together for a common cause and work for a common goal, which was to escape from hell. And they did it. That’s not something that you should take for granted.

There’s also a sense that perhaps they’re ready to talk about their lives in a way they maybe weren’t until relatively recently.

That’s exactly right. When we were interviewing them in the 90s and everything was fresh and new, obviously dudes are not going to want to talk about their history in drug dealing and stuff like that. They certainly don’t glorify it, especially people like Method Man. Even when I was talking to him then, back in the day, he was like, he never wanted to do this. He was kicked out of his house by his mum and he had hurt his leg, and he had no other way to survive. People are forced into that type of lifestyle when really, they have so many talents they don’t even know about. That’s what really intrigued me about the group.

You suggest in the book that the group members – all of whom had grown up around drugs and gang-related violence, many of them had seen people killed – would have been suffering from undiagnosed post-traumatic stress disorder. The implication is that their art became a form of therapy.

Whether the environment was good or bad, these guys just mined whatever they could out of it just to help them make sense out of life, and just how to deal with life in a society that was totally against them. These are kids who came up in trauma. Imagine seeing someone being killed when you’re five years old – that’s bound to have an effect on you. In Iraq, I was exposed to an explosion that was a little too close, and I will always remember that explosion. Even when I see a Hollywood movie now, it’s just not the same, because when you have experienced something like that, when you have experienced war, it’s a whole different ballgame. So when you’ve experienced stuff like crime and robberies and murder and drug dealing, it’s bound to have an effect on you.

You concentrate on the period between the first two group albums and that run of terrific first solo records, implying that what followed didn’t quite stand up to the same level of scrutiny. That’s by no means a rare view of the Clan and their output. But is it fair to think in those terms? And if so, what do you think was the point at which things started to go wrong for the group?

Well, I think so. And I think just speaking to members of the group that they have the same thoughts as we do as far as that first round. That first run from 93 to 97 was the very special time for Wu-Tang where it was like almost magic. To be actually living through that was amazing, and I wanted to capture that of myself – of my amazement that this same group of people were producing products that were so different, and they were so prolific. But you can only be on top for a certain amount of time. You’re not going to rule forever. I’m sorry. No one’s ever done that in anything in history. No king has ever ruled forever. There’s always a rise and a fall. And I felt like I had to reflect that, too, in the book. The fall, to me, was when Ol’ Dirty went through his stuff. And that’s why I spent a whole lot of time on that, because when you look at Ol’ Dirty’s case, it didn’t have to be like that at all.

I feel really bad for Dirty because he was a unique character. Even amidst the group, he was always kind of the odd man out. Personally, any time I saw Dirty – and I ran into him a lot on the streets back then – he was by himself. He didn’t have an entourage around him. Whereas any time I was with RZA, he was usually with several dudes. I would spend a whole day with RZA, and he had at least five, six dudes around him at all times, his brothers or his cousins or whatever. He would always roll deep, whereas Dirty, when you ran into him, he’s alone or he’s at a Burger King or something like that. And that was the nature of Dirty.

To me, Dirty is like the heart and soul of Wu-Tang. He is the Witty, Unpredictable Talent And Natural Game. He’s always on. He’s always performing. And it’s not like he’s performing, because that’s how he really was. You just couldn’t pigeonhole the guy. I’ve talked to his family members, and even within his family he was the clown, the entertainer, from a young age.

What’s next for you?

I’ve been working on kind of a memoir. It’s more like a travel memoir, I’ll call it, because each chapter takes place in a different country. Places where I’ve lived, places where I’ve worked. Iraq is one. I talk about my time working there. Obviously Sri Lanka is in there. Japan is in there. Egypt, Jamaica, Brazil. Crooklyn is definitely in there, even though it’s not having to do with the travel thing. It’s called Gen Next: Passages From The Path Less Travelled, which is kind of like the path that I took.

I’m finishing that up, and beyond that, I’m also doing a newsletter on a new platform called Bulletin, on the golden era of hip hop. It’s called Rebel Without A Pause and you can go to rebel.bulletin.com and subscribe to it. I resurrect my old interviews and recollections, talk about this or that artist and why they’re important. Basically a trip down memory lane. We should remember these artists when they’re still alive.

From the Streets of Shaolin: The Wu-Tang Saga by S.H. Fernando, Jr is published by Hachette