I vowed to have a screen-free day. I broke my vow an hour after breakfast, when I began painting and realised I needed an image saved in my phone as a light reference, but renewed said vow by noon, before making a discreet exception after lunch wherein I quickly hopped online with the intent of buying a secondhand copy of Anne Fadiman’s Ex Libris. This act was self-supported by the flimsy reassurance that I was, in buying secondhand, helping to save the planet if not my local independent bookshop.

While searching for a certain cover, I was sidetracked by Kerri Jarema’s article in the digital magazine Bustle, which claimed that Fadiman’s book defines “the difference between readers who abuse their books and those who don’t.” In her essay titled Never Do That To A Book, Fadiman writes of a chambermaid who, each morning, picked up the book left face-down on the nightstand by Fadiman’s brother, and, unable to stand this loutish behaviour any longer, wrote a firm but gentle admonishment on a scrap of paper before replacing the book on the nightstand.

The article had barely reached its stride and I was already sensing the implication that I, someone who regularly and deliberately dog-ears books, was not a ‘book person’ because of this. And had I ever left a book face-down on a nightstand? Of course I had. Not just once, either, I thought, staring resignedly at the screen in acceptance of my indictment. My finger hesitated over the keyboard; was this Jarema’s voice, or would I discover that Fadiman, like the chambermaid, was also accusatory, the kind of booklover who is somehow, despite having read widely and inhabited many lives, and therefore ideally open-minded and forgiving, unable to accommodate the practices of others when they differ from her own?

When I worked at a bookshop in my early twenties, any given day could present discussions varying from which was the best children’s book of all time to why a certain era of cover design was the peak for such and such an author. These discussions about reading etiquette often became endearingly niche; booklovers are frequently pedantic, and it is heartwarming and often amusing to see them defend their corner so adamantly. I joined in, of course – it was one of the great joys of working in a bookshop.

There was one dispute, though, that I would take great caution in joining: to dog-ear or not to dog-ear. How to mark your page is possibly the oldest debate in the annals of reading etiquette history. Everyone has an opinion, even people who seem to care little for reading as a pastime. Bookish people in particular love to affectionately hate those who treat books differently to the way they do, but more than this, they love to let the discussion bubble over until it begins to produce sparks of genuine ire and divides the warring parties, who until that point had only been offering friendly fire.

Having spoken to many fellow readers about how I treat books, I’ve come to realise that ‘ruining’ a book – dog-earing, placing face-down, notating in margins – is often interpreted as careless mistreatment. I, too, feel a trickle of sadness and disappointment in readers who claim to love books but treat them badly, but the issue is not what you do to a book – it’s why you do it. I don’t ruin my books out of carelessness. I ruin them out of love.

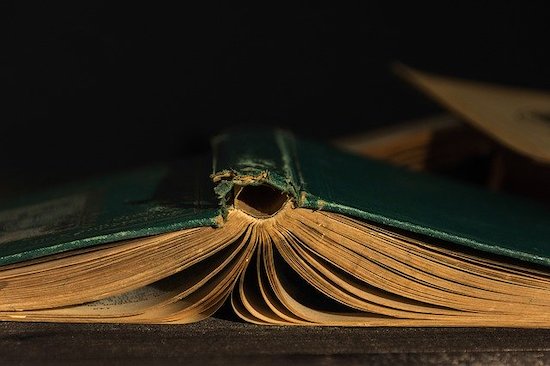

Some of my books are damaged because I bought them that way. If you can love a beautiful old illuminated manuscript with crackling parchment and dust between its pages because it has a history, why not love a charity shop paperback with a tea stain emblazoned like a house sigil on the cover? It too has a history, albeit less majestic. In secondhand shops, I always hunt for a classroom edition of those great mid-century novels that remind me of English literature lessons, despite never having studied any of the following: To Kill A Mockingbird, Lord of the Flies, The Great Gatsby, The Grapes of Wrath, Catcher in the Rye, Catch-22, Slaughterhouse 5. Old sellotape holding the signatures together, as crisp and gold as desert sand. The sloping fluorescence of a highlighter; scribbled notes and pencilled marginalia; the indentations of a scratchy, regulation HB. Beauty.

My love of old and battered books grew into a love of old and battered things in general; broken things, things that have survived the years, but which others may not care for or have long forgotten about. I even extend this to the last can of beans on the supermarket shelf, the one no one else would buy, so dented that it could cripple your can opener for life. I’m sure the beans inside are much the same. Who needs a pristine can of beans anyway?

I grew up with a father who used to pull the first few things off the metal rack in the store, convinced that not just the first item but the few placed behind as well would have been manhandled, and therefore be lesser in quality. While working at the bookshop, I saw so many customers put a slightly battered book aside to reach for it’s perfect sister at the bottom of the pile that the idea of relegating a ‘ruined’ book to the trash heap grew to be a source of genuine discomfort, especially when I discovered what happened to those books that were no longer deemed sellable. They were pulped or burned – yesterday’s pristine stacks were today’s leftovers, the victims of a hasty rifling-through or a bag that had brushed past with too much vigour. To me, that was carelessness: booklovers who treated their chosen book with a near-religious reverence with no regard whatsoever for the next customer, who would have to settle for the battered copy they left behind. This one has a mark, have you got another? It’s a gift, you understand – if it was for me, I wouldn’t mind, but it’s a gift…

When my shift at the bookshop came to an end, and there was finally time to go and buy what had been tempting me from the shelves all week long, I made sure to check every copy, searching for the dog-eared corner or the scratched spine, for the place where the shiny cover had dulled in a crease, for this was my book: the one I’d be happy with, the one I would love. The idea of choosing a perfect edition was almost laughable – what if my bag was knocked by a stranger in their rush-hour haste, battering my perfect book before I even got it home? What would have been the point, and would I love it any less, or shake my head when giving it as a gift to a friend, I’m sorry, it was fine when I bought it, but the bag was rubbish, and it was so busy on the train…

Hey, savage, you might bark, ever heard of bookmarks? Bookmarks: the respectable solution to a bad memory for page numbers. But bookmarks always seem either too forced or too cheesy – memories of souvenirs bought from gift shops as a child, my sister’s hand-me-down science museum bookmark, fat navy leather with a tassled edge, planets painted in red and gold. Robust, but hefty, and thick enough to break the spine just as easily as my bending the pages would do. I’ll sometimes tuck a postcard into a book if it suits, but, sadly, there is not a postcard for every book.

It later transpired in Jarema’s Bustle article that Anne Fadiman’s family were in actual fact in favour of “loving a book to pieces”, with some needing to be stored in plastic bags after several reads just to keep them together. Fadiman goes on to establish the two kinds of booklover: the courtly and the carnal. For the courtly, the book’s form is not to be tampered with; book as object and book as vehicle are one and the same. But for the carnal, which Fadiman claims to be, “a book’s words were holy, but the paper, cloth, cardboard, glue, thread and ink that contained them were a mere vessel, and it was no sacrilege to treat them as wantonly as desire and pragmatism dictated.”

I cannot place myself into either camp. For me, the book’s form goes hand in hand with it’s content – the shape of a paragraph, the placement of a word, the satisfaction of turning a page, then flipping it back to check a detail are part of the experience of reading a particular story. A book is certainly not a mere vessel to be disregarded.

That said, I cackle in outraged delight when a book falls into the bath. It thrills me when a thin slab of pages break free from the spine and land with a soft sloomp onto the sofa – it’s like a little knowing nod, the book saying this is the part you read and re-read; this is the place when I turned from a book you liked into a book you loved and couldn’t put down.

The very best thing is to see my books wilt as I progress through them. I know where I’m up to because I can divide the book into two sections: the bent, beloved pages I’ve poured through, and the pristine block of unopened magic yet to come. A book waiting to be read, and the act of tsundoku – allowing unread books to pile up while you await the right time to begin their journey – is a beautiful thing. A pristine, unread book holds promise. But a pristine, read book is cold and sad. I feel as though I haven’t loved it. I haven’t made a mark on it – have I even held it?

In short, the idea that only a book which remains pristine after reading is a book well-cared for is a notion I find bewildering. Many books are built in such a way that even the most delicate of reads will crack their spine, and I refuse to sit upright with a book held level to my eyes, peering into the curvature where the pages join, disrupting the flow of the prose and the act of reading itself, simply in order to preserve the book’s integrity. Reading is a time for slumping, for pulling your feet up onto the bed and laying back against the pillows. It takes me back to my pure self, my sloppy childhood self, my self who can sit still for a while and be allowed to daydream and journey beyond the everyday.

And what about a cup of tea? A book and a cup of tea. If you can teach me to hold a cup of tea in one hand and a book in the other while keeping the spine intact, and not turn the task into a Victorian exercise in deportment, then perhaps I will stop breaking my spines.

(A small clarification: this only applies to books I myself own. Books borrowed from friends or lent by the library, lacquered textbooks, archival books, artist monographs with giclée prints as glorious as the artworks themselves – to these, different rules apply.)

I wonder what the so-called courtly lovers, those who claim to care more deeply for their books than the carnals, do when a book – accidentally or not – does fall apart? There is no mention of this in Fadiman’s essay. It’s all well and good talking of damage prevention, but what about after the fact? Do they keep the book, knowing it’s ruined, or do they pass it on, stop loving it – perhaps even throw it away?

I’ll say one thing for loving battered books: it has made me more accepting. My sister once took my copy of Bret Easton Ellis’ The Rules of Attraction on holiday with her, bringing home an unrecognisable volume: a week spent poolside had caused it to open like a flower, water-wrinkled pages bleached by the sun, wet-to-dry-in-ten-seconds-flat, and it sat in her hand like a Japanese fan when she pulled it from her suitcase and offered it back to me with a smile. Her friend, stood nearby, was shocked when I beamed – your sister is going to kill you, she had said by the pool. No, my sister had replied, she’ll love it – and of course, she was right. I could easily have kicked up a fuss – the book was outrageously damaged, even by my standards – but what had changed? I hadn’t read it yet, hadn’t been able to find my way into it. The purple cover with its yellow writing and cool silhouettes was otherworldly to me, garish and unapproachable. I’d heard it was a good story, and was determined to know why, but I walked past it on my shelf for years. Now, it was transformed, and the sound of those crinkly pages was something straight out of heaven.

I know there exists a multitude of booklovers whom my arguments will not sway. ‘Ruining’ a book, to them, is disrespectful not just to the author, but to the idea of books themselves: the privacy of them, the fact that they are unlike anything else in existence, dissimilar even from their printed kin of newspapers, journals and magazines. A book is sacred and sacrosanct. You must not, under any circumstances, place it face-down on the table, and you are at perfect liberty to pour scorn on those who do, because you yourself have never done anything of the like, would never, not even when your mind was elsewhere or you had reader’s block, unable to get into the story so beloved by all your friends; not even when all you wanted to do was toss the book on to a neighbouring seat, or let it slide from your fingers as you slipped off your lounge chair and into the pool, gliding carelessly from an imagined world into the real one, not worrying about crumpling a page but diving head first into the present moment with no other thought than that of the blue laid before you.

By loving the battered and broken, I have learned to take comfort from allowing things I own to weather a little damage. If I can still love something after it’s ruined, I can hold on to what I love for far longer. And perhaps I give in to entropy – perhaps I love a book more when it’s weathered and used than when it’s the way it was supposed to be. Over time, as I re-read it, it will fade organically anyway; a page or two might slip from its signature, the glue giving out, giving in. Is a book that is ruined at thirty years old worthy of more love than a book ruined at three? Can’t you see the marks of love on every book I’ve read? The over-zealous folding of a bottom corner when a page holds a passage I never want to forget; the page with its top corner folded down, too, so that it looks like a side-turned trapezoid, the words overleaf mingling with those on the recto, right-angle sentences running away from me. A cover that peels into slices, bright images sandwiched between creamy paper and wafer-thin lamination, the book revealing what it’s made of, just ink and paper and time. There’s a note at the very start – a gift from a friend perhaps, with a notation of the year, or a lyric that, despite all my efforts to suppress sentimentality, danced so close to the story at the time of reading that I couldn’t help but write it peacefully in the top corner of an end paper. Size 0.5 pen nib, barely there in a swirling scrawl. You were here, once. This is what you were thinking, feeling, when you first read this book. Tenuous links only I know, inextricably bound. Tell me how that is ruinous.