The journalist Orlando Crowcroft has just published a book called Rock In A Hard Place on the Zed imprint concerning the rock, rap and metal scenes in the Middle East and how they intersect with various political and religious realities of the region. In this extract he tells the story of several Syrian metalheads who fled war-torn cities such as Aleppo, their perilous journey out of the country and to the refugee camps of Europe and how their dreams of being part of a larger heavy metal community still survive despite the odds.

Syria

There was a point, adrift in the open sea, the engine gone, the rubber boat half deflated, the screams of men and women all around him, when Adel Saflou found himself singing. They were lost in the Mediterranean and the 50 men, women and children who clung to the rails of the dinghy were hysterical. Adel had managed to get his phone working and dialled the number the people smugglers in Izmir had given him for the Greek coastguard. Now he was on hold and there was music was playing over the line as he waited to be connected and then he released what he was listening to: it was Somewhere Over the Rainbow. “I was thinking: Oh my god, am I really listening to this? And everyone else is screaming, everyone is screaming and crying and I am looking at them I am humming along,” he said.

Eight hours earlier Adel had been packed into a van with two of his cousins, their children and some neighbours from his home city of Idlib, close to the Syrian border, as well as dozens of strangers. The Turkish-Syrian smuggling gang had promised the family that their boat would have 25 to 30 people but it was clear when they arrived that they had been lying. Adel and his cousins had paid $1,200 per person to cross from Izmir, in Turkey, to Samos, in Greece. He had toyed with the idea of buying his own boat – which went for around $3,000 in Turkey – and crossing himself, but considered it too dangerous. He had heard that the smugglers would often pursue boats that tried to cross alone and puncture them when they were at sea. They were offered a speed-boat crossing for $3,000 each but had been told that often those who paid more would end up in the same boats anyway. In the summer of 2015, Izmir was full of Syrians waiting to make the crossing and word travelled fast between friends and family about the ruthless tactics of the smuggling gangs. “They are smugglers – they’re criminals – in the end. They don’t want you to be happy, they just want money,” he said.

On the beach, Adel helped some of the younger kids put on their life jackets. It was a warm night but the water was cold as they waded to the boats. Adel had all of his cash wrapped in plastic and taped to his chest. They packed onto the boats, families sitting as close together as possible but children and heavier passengers shifted around to maintain the weight. The last person to board looked bemused as one of the smugglers handed him the tiller to the small outboard and then pointed out to sea, towards a twinkling crescent of lights in the distance. It was Greece: yallah: go – that way, he said, and pushed the craft into the swell. “No one knew what they were doing,” Adel recalled. And why would they? Like Adel, many of the refugees packed into the boat were middle class Syrians from metropolitan cities like Idlib, hundreds of miles from the coast. An experienced skipper would struggle to pilot a heavily overloaded dinghy with no lights, no radio and no navigation system across 50 miles of open sea. Prior to the outbreak of Syria’s bloody civil war, many of Adel’s fellow passengers had regular lives – jobs, homes, families and friends – and yet they had found themselves chased out of their cities into refugee camps in countries that didn’t want them. In Istanbul and Izmir they had had to negotiate safe passage for a fair price from criminal gangs. Now here they were, together, on the open sea in a final bid for sanctuary in Europe.

The sea was manageable in the first half an hour of the crossing but as they left the safety of the Turkish coast for deeper waters, the current and wind whipped up huge waves all around them. As water sloshed over the edges of the dinghy – already low in the water – people jammed themselves together to get away from it. Panic came quickly: “People were standing up. A lot of people were screaming, others were telling them to calm down. Then people started getting agitated and more water started coming in the boat,” he said. Adel quickly released that they were sinking and he and his cousins considered diving into the water and swimming, but the huge peaks and troughs of the swell made it impossible. At one point, a man leapt into the water but quickly faltered in the cold water and the others were able to drag him back over to safety. In the centre of the boat, where families were now crammed together, people were already screaming at each other: “People were shouting: ‘Don’t touch my sister!’ and ‘I’m going to kill you’ and ‘I’m going to slice your throat’,” Adel said. Then the make-shift pilot lost his temper and began wrenching at the tiller furiously. The engine came loose dropped into the ink-black water. The boat was adrift. Their only hope now was rescue.

[INSERT]

Adel had already left Syria when the rebels stormed his home city of Idlib in 2015 and converted the house he grew up in into a makeshift military base. His family had fled hours earlier after three years of living on the front line between the forces of Bashar al-Assad and the al-Qaeda-affiliated Jabat al-Nusra rebels and eventually made it to refugee camp in southern Turkey. Adel was in Beirut, where he had moved to in the early days of the war, and heard the story later from neighbours. “The rebels went into my room and it was painted dark red, all over. I had a big sword and two guitars and a painting of a pentagram. It looked really ritualistic,” Adel said. On his shelves were books about heavy metal and CDs of bands from Europe and the US, while his walls were covered in pictures of shows he had attended in Syria and further afield. His pentagram, which he had drawn on the wall in black candle wax, must have been a shock to the Sunni rebels: “They saw my picture and they said: ‘We want this guy he’s a devil worshipper.’ And now they have my name I guess,” he said. “I don’t care. I am never going back there.”

Growing up in Idlib it was difficult not to be swept up in the tide of anger towards Bashar al-Assad’s Alawite regime, which had long marginalised Syria’s Sunni majority. Sunni Syrians like Adel had grown up in households that had witnessed Assad’s father, Hafez, brutally repress a Muslim Brotherhood uprising in the 1980s, culminating in his razing of the city of Hama and killing over 20,000 people. While Assad’s Baathist movement was ostensibly secular, in reality Hafez and Assad’s Alawite sect dominated positions of power and influence in pre-war Syria while his secret police kept a restive Sunni population in check. Even if Adel was not overtly political – let alone sectarian – growing up, a hatred of the Syrian government was in his blood: he remembered clearly when he was eight or nine that he and his friends would go down to the main square in Idlib and spit at the statue of Hafez.

Adel grew up religious. He prayed often and his mother and father were devout Muslims. He also loved video games. In his early teens he bought the The Need For Speed, the soundtrack to which included music by Avenged Sevenfold and Bullet For My Valentine, and as he raced cars through digital renderings of American cities or lush mountains he would look forward to the songs by these popular mid-2000s bands, then at the forefront of a popular genre known as ‘metal-core’. On Syrian TV he first heard the Foo Fighters, the Gorrillaz and Avril Lavigne, who were then topping the international charts, and after school he would go home, turn on the television and jump on his bed to the music. Then in his early teens he was hanging out at his cousin’s’ house in the nearby town of Mera’a when he first heard Opeth, and his life changed forever: “I got hooked,” he said. “It put a spell on me.”

Adel managed to get hold of a classical guitar and began practicing playing heavy metal songs at home. He migrated from Avril Lavigne to Metallica and Godsmack, and gradually got hold of heavy metal garb: spiked and studded bracelets, black band t-shirts – from the very few shops that sold them. He began going out with ‘666’ and pentagrams drawn on felt tip pen on his hands. He got his first piercing. But his new passion for heavy music, alternative fashion and the symbols of the occult did not go down well in conservative Sunni Idlib: “Metal was still really frowned on then. My family said it was devil worshipping. They all made a big deal out of it. It gave me a headache,” he said. Then in 2010, Adel moved to Aleppo with his mother, who took a teaching job in the city. Aleppo may now be a byword for destruction and death after years of bitter conflict, but it was once a relatively liberal financial hub of around two million people. It was also, alongside Damascus and Homs, one of three hubs for the Syrian metal scene. Adel quickly fell in with the crowd there and formed a band with scene stalwart, Bashar Haroun, who ran U-Ground Studios, then the main hangout for Aleppo’s metallers. “It was easy to form bands in the studio. You were just sitting there and people would be like: ‘hey you want to join a band?’ Everyone played something and the best players always knew who to pick,” he said. His band, Orchid, only rehearsed three times before their first gig in 2010 and Adel only remembers now that it was at a bar called Cheers in Aleppo and that only 70 people turned up. After that, they continued to organise shows and the crowds grew: “For two years it was amazing and the studio was like a home. I spent most of my time there playing music. We’d smoke and talk and laugh and we’d get drunk,” he said.

Most of those who lived through the protests that began in Syria during 2011 describe it as an overwhelmingly positive movement, an observation that is perhaps hard to fathom given the patchwork of bloody violence the country’s revolution has become. It was also a movement that crossed the sectarian divide, bringing Sunni and Shia Syrians onto the streets to protest against a shared enemy – the Alawite clan of Bashar al-Assad. But it wasn’t even sectarian in its opposition to the Alawites, a Shia sect that originated in Iraq in the 10th century and venerate the Prophet Mohammed’s cousin and son-in-law, Ali. Alawites made up 12% of Syria’s population prior to the conflict in 2011 and until very recently had been seen as staunch backers of Assad, with members of the sect and in particular those related to either the Assads or the Makhlouf, Assad’s mother’s family, dominating positions in the army, the security services and the country’s business elite. Assad’s brother, Maher, controlled the country’s Republican Guard. His cousin, Rami Makhlouf, is Syria’s richest man and perhaps the most reviled man in the country after Bashar and his late father. Syria was a brutal police state where endemic corruption enriched a small elite close to the ruling family. Assad deliberately exploited sectarian dimensions in the country in order to divide and rule Syria, which is 74% Sunni, but although the revolution began in Sunni-majority cities such as Homs and Hama, it was broad coalition of Shia, Christians, Kurds and Sunnis and its target was – above all else – rampant corruption and the violence of the security services.

When Assad assumed power in 2000, observers had been positive that the London-educated ophthalmologist would bring Syria in from the cold. Assad had only returned to Syria after his brother and Hafez al-Assad’s heir-apparent, Bassel, was killed in a car crash, and one of his first moves on taking office was to release hundreds of political prisoners. In Assad’s first speech to the nation on July 17, 2000, he spoke of democracy, transparency and creative thinking but in a damning report in 2010 – a decade after he took power – Human Rights Watch ruled out any indication that he would atone for the sins of his father. It documented how Syria’s mukhabarat – or secret police – detained Syrians without warrants and how prisoners were routinely ‘disappeared’ by the security services. Meanwhile minorities such as the Kurds – which make up 10% of the population – were still forbidden from celebrating Kurdish festivals or learning the Kurdish language. Between 2007 and 2009, prominent writers, bloggers and human rights lawyers would be jailed in most cases simply for speaking out against the Syrian regime. By 2010 the arrests and disappearances were continuing with abandon.

When the Arab revolutions began in Tunisia 2010 and in Egypt and Libya at the beginning of 2011, there was immediate speculation that Syria would be next. It had been decades of corruption and violence of dictatorial Arab states that fuelled the mass protests that would eventually oust leaders in Tunisia and Egypt and the conflict that would unseat Muammar Gaddafi in Libya. Syria’s Baathist state was no less violent or corrupt. But towards the end of January 2011, Assad told the Wall Street Journal that Syria would be unlikely to see protests such as those that were already raging in Tunisia and Egypt because he understood the needs of his people, unlike Gaddafi, Hosni Mubarak and Zine Abidine Ben Ali. On 15 March, Syria defied him and crowds took to the streets of southern city of Dera’a to call for the release of political prisoners and an end to corruption. The protests were sparked by the arrest and torture of 15 children for spraying anti-government graffiti. Assad made limited concessions as the protests grew to other Syrian cities including Hama and Homs, including lifting a 48-year-old state of emergency and releasing dozens of political prisoners. He also made concessions to Syria’s Sunni community by lifting the country’s ban on women wearing the full face veil – the niqab – and closing the country’s only casino.

But from the earliest days of the conflict, Assad also responded to the protests with violence, with soldiers opening fire on crowds and tanks surrounding restive cities. Tens of thousands of opposition activists were rounded up in door to door searches in cities such as Idlib, and both Deraa and Hama came under siege as government tanks surrounded the city. Despite the violence, 400,000 gathered in Hama at the end of June. At the end of July 2011, a group of Syrian defectors founded the Free Syrian Army (FSA) with the express intention of forcing Assad from power and by December Damascus had seen its first suicide bombing, with 44 people killed. The Syrian regime began the bombardment of Homs and Hama that continued into 2012, and with every report of mass civilian casualties, the protest movement grew. In Aleppo, Adel, who finished school in the summer of 2012, saw the escalation first hand when he returned to Idlib, which had been an early conquest of anti-Assad rebels before being seized by the government in April. The city was a battleground. Syrian regime thugs were going door to door seeking out rebel sympathisers, which often simply translated as young Sunni men, with rebels camped on the outskirts. “It was terrible there,” he said. Even from a practical perspective, Adel wanted to study English and even in peacetime the universities in Idlib did not offer it. Likewise his musical ambitions were hardly going to be satisfied in a city already torn by a spiralling conlift.

But there was also a religious dimension: Syria’s conflict had not yet taken on the horrific sectarian dimension that it had by 2013. Syria-sponsored Shia millitant group Hezbollah had not yet entered the war on the side of Assad and Islamic State (ISIS) were still a ragtag group of Sunni militants hiding out in Syria’s eastern deserts. Saudi Arabia, Qatar and Turkey had not yet started funding Sunni groups such as Jabat al-Nusra and the Free Syrian Army was still a credible – and cross-denominational – political force. But it was still clear to Adel that the conflict was going that way. It was not safe for a Sunni – not least one who walks around with piercings and ‘666’ written on his hands – to remain in Syria. “For me as a musician and a guy who is 18 or 19 years old with a [Sunni] Muslim name: It is not a good idea for me to stay in Syria – anything could happen. I don’t want to waste my life or test my luck.” Like an increasing number of refugees from Syria, Adel packed his bags and headed for Beirut.

[INSERT]

Yasser Jamous got hold of his first hip hop album in 2001 by accident. His uncle, a passionate break dancer, had sent him to a music shop near his home in Yarmouk, outside Damascus, to pick up a mix tape. Yasser headed to his local music store with a blank cassette and a list of the tracks that his uncle wanted, but when the owner had finished copying the songs he said there was still 30 minutes space. The owner started talking about an American rapper who had just released a new album, and said he’d put as much as he could of it on the end of the tape. That was how a teenage Palestinian refugee in the Middle East’s biggest refugee camp discovered Eminem: “I liked his music,” Yasser said. “It was commercial but it was my doorway into hip hop.” From there Yasser began looking into the roots of Eminem’s music: Tupac, Biggie Smalls and NWA. “It was crazy. It just had this amazing energy,” he said. Yasser began writing out the lyrics to his favourite songs and looking into the meanings, and found that the life that rappers like Eminem, Tupac, Biggie and Ice Cube were describing in Detroit, Brooklyn and Los Angeles had parallels with his own as a refugee, growing up in a large and impoverished area of Syria where violence was never far away. “I started to feel the lyrics and the idea of resisting. I felt that there was real issues inside this music,” he said.

Prior to the war, Yarmouk was home to around 160,000 people, most of them Palestinian refugees that were forced from or fled their homes after the foundation of Israel in 1948. Unlike the refugee camps of Turkey or Jordan today, Yarmouk was not a sprawling tent city but a shabby suburb of Damascus that had been developed over 60 years, with shops, restaurants, roads and businesses. Like the camps of the Palestinian West Bank, Yarmouk was a functioning city-within-a-city – unlike the West Bank, Palestinians living there were free to travel into Damascus or elsewhere in the country relatively freely. Like Palestinian camps in Jordan and Lebanon, various districts of Yarmouk were operated by factions of Palestinian militias including some that no longer existed anywhere else in the Middle East. These included the PFLP-GC (Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – General Command), a breakaway of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), the Marxist militia that made its name with a spate of plane hijackings in the 1970s and 1980s. As a result, while many Yarmouk residents were born in Syria, Palestinian identity was strong in the camp and it was Palestinian flags and the colours of the militias – red for the PFLP, green for Hamas – that flew on the houses.

Palestinian Yarmouk residents were not Syrian citizens – they were guests – and infrastructure, sanitation and resources in the camp were far inferior to Damascus or other Syrian cities. Just as the music of Eminem documented the US rapper’s experience of growing up on the wrong side of Detroit’s Eight Mile Road – where poverty was rife and prospects for young people slim – so Yasser and Mohammed’s early lyrics documented not only their identity as Palestinians but the day-to-day lives of young people in the camp. The pair began to write in English before shifting to Arabic and until 2006 kept themselves to themselves, recording a couple of songs through a microphone attached to their family computer. They were convinced that they were the only people in the Middle East rapping in Arabic. But one day they headed to an internet cafe and Googled ‘Arabic hip hop’ and came across a Palestinian site with some songs by DAM. But they were shocked to also find another site dedicated to Syrian hip hop and featuring bands from Homs, Aleppo and at least two from Damascus. “It was a shock,” Yasser recalled. “My brother messaged one of the guys and said we liked his song and if he was in Damascus we should meet. He replied: ‘OK, where do you live?’ and we said Yarmouk and he said: ‘What the fuck? I am in Yarmouk too’.” Muhammed Jawad introduced Yasser and Mohammed to a fourth rapper, Ahmad Razouk, an Algerian. At a meeting, the group decided to work together on a song but couldn’t decide on a name: two of them were Palestinians, one was Syrian and the other was Algerian so at least three quarters of the band were refugees: that was when they decided on Refugees of Rap. The name was to take on a new meaning a decade later when the group were forced to flee Syria, but even at a relatively peaceful time they thought that the word refugee was fitting: “We thought all of us were refugees to rap music. We take rap music as a place to be free and write our lyrics, to find asylum. It was not political, it was more for us as teenagers to be released,” Yasser said.

The first songs the brothers recorded on their computer was a love song and their second was about hanging out in their neighbourhood. But the first song as a band was different: “It was about us and rap and what it meant to us. It said: ‘Forget the TV, we are the new TV. We will tell you the truth. It was a teenage rebel song,” he said. As Facebook and YouTube were blocked in Syria, the only way to publish songs was on the music sharing site MySpace and the Syrian hip hop site, which was administered by another Syrian rapper called Mohammed Abu Hajjar. They contacted Abu Hajjar and when he put it up positive comments quickly began to pour in. They also had more elaborate ways of sharing music, such as with bluetooth between mobile phones in the streets of Yarmouk. At a time when very few computers in the refugee camp were connected to wifi, bluetooth sharing made Refugees of Rap go viral in the camp long before going viral itself went viral. “The way was to send it to a friend who sent it to a friend and so on. But after a week we started to hear our song in the street. We’d be walking along and we’d hear our song being played in a car and I was like – this is me! But nobody knew who we were.”

The song grew in popularity with young Palestinians and Syrians in Yarmouk but the older generation were less receptive. Palestinians had long valued their traditional music and in particular songs that spoke of their exile and their dream of return to Palestine, but rap was seen as an alien genre – particularly if it didn’t have an outright political message. But the group’s next song: ‘Palestine and the Decision’ ticked those boxes. It was a direct attack on Arab states that had failed to support the Palestinian people and push their homeland. It accused Arab nations including Syria for abandoning millions of Palestinians to a life of exile. It was an angry, upbeat and aggressive anthem that was far from the maudlinism of traditional Palestinian music. “It was a hit,” said Yasser. “We counted and between MySpace and Reverbnation it had around 200,000 downloads in the first two months and then hit 500,000.” They were contacted by rappers from Palestine who wanted to upload their song to a new hip hop site, Palrap. This allowed the band to contact other rappers from across the Middle East and put their first album together, the self-titled Refugees of Rap. They recorded one song at home and four more in a local studio, which was a huge expense. “We didn’t have any income and our parents were not good situation financially. We suffered to get the money to go and record – sometimes we would have everything prepared but we didn’t have the money for transport. We had the money to record but not to get to the studio,” he said. The band also began performing at local clubs between DJ sets. But by 2008 Refugees of Rap were doing so well that they would be asked to go on Syrian TV channels and perform concerts in Damascus.

As their profile grew the band struggled to get their increasingly political message across without falling foul of the authorities. Lyrically, Yasser and Mohammed began relying on metaphors and allusions to their politics rather than outright criticisms of the government. They also benefitted from the fact that hip hop lyrics are spoken so quickly that many of the secret police officers at their gigs simply didn’t have time to make them out. The band played in Cairo and in Beirut and at bigger and bigger shows in Damascus. When they would do TV interviews they would be asked to submit lyrics beforehand, but often because they were seen to be Palestinians talking about the Palestinian struggle rather than Syrians criticising the Syrian regime, they got away with more than a Syrian outfit would. The authorities were less tolerant of songs criticising the regime in Algeria, and were at least once banned from performing those songs on TV. “When we went to Syrian TV they introduced us as Syrian and on Arab TV as Palestinian. But we preferred not to be identified as a nationality. We were refugees and we wanted to be introduced as that, to not have this idea of nationality,” Yasser said. They recorded another album, Face to Face in 2010 which included their first anti-regime song, ‘Age of Silence’. They debated whether to release the song once the revolution began in 2011 but opted not to (it would not be made public until 2013). “We didn’t release it fast enough, It was negative I think but we had been in danger – sharing the song in Syria was a crime,” he said. The band concluded that with checkpoints throughout Damascus and with their families still living in Syria, they could not in good faith release a song that would endanger the lives of those they loved. “We decided we would find a way to get out and after we can do this,” he said. In 2011, Refugees of Rap set up their own studio, Voice of the People, allowing them to work – albeit briefly – in relative freedom but in 2010 they had to rely on other studios in Yarmouk. Yasser remembers that the engineer recording the song was so nervous about its content that they had to attend session in the middle of the night. The revolution was building in Syria, but so was the government’s response to it.

While Homs and Hama were quickly captivated by the protests that began in 2011 in Deraa and spread to the major cities, including Damascus, the revolution was less well received by many in Yarmouk. Many of the Palestinian factions that controlled the camp were loyal to Assad before the rebel movement and those that had TVs had seen the chaos that was unfurling in Libya and Egypt. Yarmouk was poverty stricken and heavily reliant on aid, but unlike in other Middle East countries, the Syrian regime permitted Palestinians to own property and to work. In the same way that many Palestinians had supported Saddam Hussein because of his ongoing belligerence towards Israel (compared to Egypt and Jordan, who both signed peace deals with the Jewish state), many Yarmouk residents saw Assad as an ally in their struggle for a Palestinian state – not least given his open hostility towards Tel Aviv over Israel’s occupation of the Golan Heights. “People were angry because of the actions of the regime but they were afraid have the scenario of Libya. People were confused. In Yarmouk there was not really one opinion, there were many – even in one family. My uncle said this would take Syria to the shit, his brother said this will make Syria better,” Yasser said.

But what turned opinion in Yarmouk was the brutality with which Assad dealt with the early protests in Deraa, which was besieged by the Syrian army. Yarmouk residents watched the footage of death and destruction with horror on YouTube and protests grew. As the rebels made inroads into the camp – which is a crucial frontline for advances on Damascus – life became more and more dangerous. Government air strikes began in 2012 and Yarmouk residents took to the streets on 14 July in a mass protest: “I remember more than 80% of the camp was in the street the rest were on their balconies, throwing water to help people cool down. It was very hot but the whole camp was there,” he said. As the army responded and three Palestinians were killed. The Free Syrian Army entered Yarmouk in 2012 and Yasser and Mohammed decided that enough was enough. Daily air strikes had destroyed swathes of the neighbourhood On the day they were due to leave, in December 2012, Yasser made a decision – he had to go to the studio, which was on the frontline between Assad’s forces and the Free Syrian Army. “It was ten minutes from home but it was in a place where there were no civilians. I didn’t tell my parents. I took my bicycle and I rode there,” he said. As he walked in the door he saw all of the equipment that the band had saved for months to buy and spent years accumulating. He knew he couldn’t carry the speakers, mixing desks and mics – they were too heavy – so he opened the monitors and removed the hard drives: “I would not let all that be lost. I took the disks and went back home. Six weeks later it was destroyed,” he said.

Mohammed and Yasser called in a few favours and managed to secure French visas through a series of contacts including an Italian rapper, a refugee charity, an injured journalist and finally the French Consul in Lebanon. The pair made the two hour drive from Damascus and rocked up at the embassy with nothing more than back-packs and the Palestinian refugee IDs that they were given in Syria. “I remember in embassy I asked the guy: ‘How long will this take?’ and he said sorry and that it would take a little more time. I said: ‘Like how many days?’ and he said: ‘Like 30 minutes’.” He laughed. “We were like fuck, what? I thought it would take two months.” Most of Yasser and Mohammed’s family had already managed to gain asylum in Sweden by this point but pair remain in France as, by law, refugees have to claim asylum in the country that they first arrive in.

When I met Yasser in Paris in the summer of 2016, he already spoke fluent French and the band were touring Europe with a growing profile. As we walked the streets of Montparnasse, Syrians less fortunate than Yasser and Mohammed were camped out on patches of dry grass in car parks, or slumped in doorways with suitcases and hungry-looking children. Elsewhere in Paris, dotted on the grassy banks in the parks that line the Seine, were men and women with carrier bags and holdalls, sleeping in the shade as a steady stream of tourists pass by oblivious. France was by then home to tens of thousands of Syrians, and many of them were on the streets begging. In early 2015 the country had basked in warmth and welcome for refugees from that shattered nation, times are changing. The brutal Paris attacks of November 2015 were ruthlessly exploited by those on the right, including Marie Le Pen’s National Front, as evidence as to why the country should start turning away those fleeing Syria. Yasser, who arrived in Paris in 2013 – during a different era – has been shocked at how attitudes have changed: “It is like we have gone back 50 years,” he said, drawing parallels with the anti-immigrant racism of the 1960s.

He admitted that he is lucky, to have got out when he did. Muhammed, their Syrian bandmate, is back in Yarmouk having failed to secure asylum while their Algerian bandmate Ahmad Razouk made it to Europe only to be deported back to Algeria with his wife and child, a country he had left when he was two years old. In April 2015, extremist rebel factions including Jabat al-Nusra and ISIS seized 60% of the camp and then in July typhoid broke out and spread among the 18,000 residents that remained. When the UN released an image of tens of thousands of residents squeezed between rows of shattered buildings, queuing for food, Yarmouk became yet another icon of the unparalleled death and destruction of Syria’s civil war. As well as the regular outbreaks of violence between rebel groups and Palestinian factions that still remain, Assad has relentlessly bombed the camp as he tries to decimate any rebels that stand a chance of pushing onwards to Damascus. Even if the war was to end tomorrow, Yarmouk will never be the same again. But although Yasser grew up in the camp, he chooses to look forward rather than back. Syria was his home, now France is, but he is Palestinian and until there is a Palestinian homeland, he will always be a refugee: “I was born as a refugee. Syria was a refugee camp for me. It was my country, but the feeling is difficult to describe. I didn’t have nationality there. I had a permit,” he said. “Coming to France has taught me that my soul is my country. The rest is just memories. The place where I am, this is my country for the moment until I go back to Palestine, Maybe not me, maybe my children, my children’s children. But Palestine is what I feel.”

[INSERT]

Naarden is the kind of place where people go to die, Monzer Darwish said, peering through the net curtains at the silent street from the first floor window of his flat. The tiny town is a prime destination for Dutch retirees and set in the low, green fields north of Amsterdam, just outside the tourist town of Edam – famous for its cheese. Monzer and his wife, Lyn, crossed the Mediterranean in 2015 and then walked across Europe, buying fake passports in Greece and then flying to the Netherlands, where they claimed asylum. As is the policy in Holland, they were housed first in refugee centres and then allocated a flat in Naarden. Here they spend their days watching TV and learning Dutch while Monzer, a filmmaker, works on a documentary – Syrian Metal is War – that he wrote and filmed in Syria between 2011 and 2013. Other than the TV, a couple of guitars and their cat, Monzer and Lyn’s flat is bare. When they crossed the Mediterranean they brought almost nothing with them.

Monzer grew up in Masyaf, near Hama, and remembers that it was Syria’s conservatism that brought him to metal. He was in the seventh grade and was attending a computer competition. It was hot and Monzer was wearing shorts but when he arrived at the venue a security guard told him he would have to go home and change because there were young women also competing. He refused. “I was really young and I didn’t even know what he was talking about. I said I wouldn’t change and I was kicked out of the competition,” he said. Monzer went back to his room in tears and found a friend, who was also attending the event, listening to music through headphones. “He put the headphones on me and said: ‘This will make you feel better. And it did.” The song was ‘Battery’ by Metallica and the album, Master of Puppets, was Monzer’s first heavy metal record. When he returned to Masyaf, he told his 70-year-old piano teacher what he had heard and was surprised when he dug out a cassette of Metallica’s Load and gave it to him. It turned out that the old man was also a fan and provided Monzer with three metal albums in all.

In the early 2000s, Syria’s metal scene had a large and passionate following but just as in Egypt and Lebanon was subject to regular crackdowns from the authorities. Although officially a secular state, the country is deeply religious within both Sunni and Shia communities and local bands would rarely announced that they were metal when arranging shows. There were established scenes in Damascus, Latakia and Aleppo, as well as smaller scenes in Homs and Hama, and as internet use became more widespread it was easier for bands to communicate and organise gigs. But they regularly encountered hostility: “It wasn’t the authorities it was the people: they see the word metal and think something bad is going to happen. Like there would be satanic people who are going to rape or kill cats or drink blood or take drugs,” he said. It was public outrage that was behind the government crackdown in 2006, during which Monzer was arrested. “There is no law that says metal music is not allowed or it is prohibited in Syria, but because of the people, the authorities began to arrest metalheads. And then it became a thing: automatically when someone from the government met a metalhead, they would be questioned or held.”

The crackdown was provoked by events in Lebanon and soon the pattern kicked off: articles about Syrian satanists began appearing in local newspapers, many of them featured pictures from the alternative website Deviant Art, including lurid images of young women with crosses in their mouths as well as pictures of tattoos and piercings. “They used them to say this is how metal people look and this is how they will make your children look. They attack religion, and they meant physically – they said we were going to physically attack people,” he said. The crackdown began in Homs and spread to Monzer’s hometown, Masyaf, where a popular record store was raided and dozens of CDs and t-shirts burned in the street outside. The store was then shuttered by the authorities. Then in Hama, Monzer was detained: “I was arrested for Satanism. They said: ‘You are listening to Satanic music. You are worshipping the devil. You are involved in dirty sexual acts.’ They tried to think of every bad thing they could imagine and attach it to metal. There were waves of arrests. It got really bad for metalheads,” he said.

The first time Monzer was arrested the police found a notebook in which he had written lyrics by Norwegian black metal band Dimmu Borgir. He was 15 and found himself having to explain to his interrogators that the irreligious lyrics were not meant to be taken literally: “I tried to explain but they wouldn’t listen. I had to wait for eight hours in a small room with my father waiting outside.” But the treatment only made him more determined, more passionate. “I was really extreme about it because all of that happened and I knew I wasn’t doing anything bad against anyone. I was just listening to my music. I just wanted to be in a band and make music and that’s it,” he recalled. In the end Monzer had to leave his home town of Masyaf and move to another city, Salamiyah, far from his friends and family. “I had to live alone just because everybody thought I was a satanist. I spent three years completely alone, in my house. And during those years I was just practising and writing articles, getting more music and metal bands,” he said. While he was in internal exile in his house in Salamiya, Monzer became black metal editor of a Syrian online website – which is how he met Lyn, a fellow metal fan and tattooist in Homs. He wanted her to be an administrator on the site and eventually they met and fell in love.

Bashar Haroun was flicking through the channels on TV at home in Aleppo when he came across a video of Metallica’s ‘The Memory Remains’, which had been released in 1997. He had been a fan of Michael Jackson since his early teens, but this was something completely different. Bashar remembered that the band’s style, their black clothes and their dark personas was so different from the pop music that tended to dominate the airwaves. It was serious. “It was the image of band. The type of music, the power and the energy. The anger. The ideas they had. This wasn’t ‘Kiss Me Baby One More Time’, it was deeper,” he said. “From this moment I knew that this would be part of my future. I went to the music store and bought the cassette and then started the chase: one band after another, one genre after another, but Metallica’s album, Reload, it was my first.” Being young and wanting to rebel had a lot to do with it, but as he grew up Metallica and the other bands that he sought out never lost their importance. “I needed to be different when I was a teenager but that didn’t mean when I grew up I didn’t need it anymore – it was the opposite. It is part of my personality and I live it in every moment of my life,” he said.

By 1998 the scene in Aleppo was growing. Damascus was the bigger city and Homs also had an established scene but Aleppo was its heart. “In Damascus there were a lot of people who believe in metal but in Aleppo there were a lot of people who played metal – real musicians were from Aleppo, and real metalheads were from Damascus. That was how it was,” he said. Aside from sporadic harassment from the police, the biggest problems for bands in Aleppo was making live shows break even. Typically bands would need to hire the venue and then all the equipment separately, meaning that shows were extremely expensive to put on. “On 90% of rock and metal concerts you would make a loss,” he said. Then there was the fact that Syrian metal fans tended to want to hear covers rather than original material, and as a result few Syrian bands played their own material. Bashar formed his first band in 1998 with some friends and played twice in Damascus and at least ten times in Aleppo. “We were all beginners before. We loved music but we weren’t professional in any way,” he said. And then in 2003 he formed his first serious band, Orion, and began writing his own material. In 2004, he opened U-Ground Studios, the recording venue and hangout that Adel Saflou would attend six years later and form his first band. For Bashar, U-Ground was not only a focal point for the Aleppo scene, but the result of years of frustration with producers in the city being unable to understand how to record heavy metal: “There was no-one who knew how to mix metal, with the double bass drums and the growling vocals,” he said.

The crackdown that began in 2006 and forced Monzer Darwish to leave his hometown migrated to Aleppo in 2008, and inevitably came to Bashar’s door at U-Ground. The studio was raided, their equipment and merchandise confiscated and Bashar was thrown in jail. He was moved around five of Aleppo’s nastiest prisons before being released a month later. “The charge they were looking for was something satanic or something political – and I am neither,” he said. Eventually Bashar appeared in court and was released by the judge, but the damage was done. U-Ground was re-opened but the semi-regular shows that Bashar had organised in Aleppo ceased – the city would not see another live metal show until 2010. More generally, the arrests and harassment of metallers across Syria took an axe to what was a burgeoning scene, Bashar said: “They made metalheads look ugly in front of society and everybody was scared to be with them – metalheads were scared to be metalheads. They made it look like it was something really dangerous. You might waste your life, you waste your money. They just put us in the darkest place.” Orion also went inactive, and the songs that they had written before 2008 were not recorded until two years later. Their best known song, ‘Of Freedom and Moor’, had originally been written about the situation in Palestine, Bashar said, but the crackdown and its aftermath meant that by the time it was recorded in 2010 it was about problems closer to home. It was about Syria.

It is hard to believe today but Aleppo largely sat out the Syrian revolution until May 2012. It wasn’t oblivious to the mass protests and brutal government reaction to them, but it never saw the kind of popular uprising seen in Homs and Hama. An ethnically diverse and commercial hub of some 2.5 million people, Aleppo had even witnessed government-backed pro-Assad rallies as other cities across Syria were ablaze. But by 2012 things were changing fast. On July 22, Syrian rebels invaded the city headed by the Free Syrian Army and later Jabat al-Nusra, which had been formed in January 2012 and brought battle-hardened Sunni jihadis from previous conflicts in Bosnia, Afghanistan and Iraq into Syria’s war. In a city that had for centuries been home to Christians, Kurds, Shia, Sunni and Alawites, the sectarian narrative of al-Nusra forced residents to take sides along religious grounds. This was only compounded by Hezbollah’s entry into the conflict in Aleppo in 2013. Funded by external actors such as the Sunni states of the Gulf and Turkey on one side and Iran on the other, the sectarian narrative grew across Syria. Once Syria’s melting pot, Aleppo became synonymous with the country’s shattered heart.

For Bashar, the sectarian narrative was difficult to bear. In 2010, as the authorities turned their attention to quelling the growing protest movement that was spreading across Syria, Bashar had begun organising shows. Many Syrians were already leaving the country, heading for Lebanon, Turkey or, for those who could afford it, the Gulf. But as the violence increased around Aleppo, Bashar became more and more determined that he would not abandon either Aleppo or the metal scene. He believed that his scene had always transcended the sectarian divide and could continue to do so. “We made one every one or two months. It was to encourage people not to fall into violence and just play music and just stay in the spirit of metal and rock music,” he said. During 2010, 2011 and early 2012, the concerts continued and the crowds turned out. Monzer recalled that if anything the metal scene grew alongside the violence. It was ironic that the bands actually had more freedom to perform once the conflict began in 2011. “We had the chance to do it without any distractions from the people who used to bother us,’ he said. Like Bashar, Monzer sensed that what was happening in the Syrian metal scene was important. It showed a different narrative, one of young people from cities and communities across a torn country, united by their black t-shirts and their passion for extreme music – united by the arrests, the beatings, the isolation that predated Syria’s war and will outlast it. “I wanted to document not just people doing concerts and all that but the passion that Syrian metalheads had for this type of music, because whenever something is really hard to do you develop this great passion. It wasn’t just concerts, it was something spiritual for me. When you wore a metal t-shirt back then and saw someone else wearing another band t-shirt in the street you would literally become friends – the next day you would be drinking beer together,” he said.

As Aleppo became increasingly uninhabitable, Bashar moved to Latakia, the port city on Syria’s western coast that has even today been spared much of the devastation of the rest of the country. He opened a new incarnation of U-Ground and immediately began organising gigs. Then, in 2013, at the worst of the fighting in his home city, he and Monzer returned to Aleppo to organise a live show, Life Under Siege, on the front-line between the Syrian army and the rebels. It would eventually form the basis for Monzer’s documentary although at the time Bashar had his own reasons for returning to Aleppo and putting on a gig as if the war wasn’t raging around them. He was proud then – as he is now – that during a war that has pitted Syrian against each other, not a single member of Syria’s heavy metal community ever picked up a gun. Syrians metallers were from across its religious and cultural divide – Sunni, Shia, Kurdish and Christian – and they remained so, even as Aleppo crumbled around them. “I don’t know anyone from all people around me in the music scene – musicians or just metalheads, rockers and music lovers – who has been involved in any action during this war, until this day,” said Bashar when we spoke in 2016. “I think the message was clear from the beginning, that we were away from all this. We are still living our own lives that are different from war. We didn’t care about the problem of ethnic religion or politics. We didn’t talk politics. It was just about metal. We were just one happy family,” he said.

The gig was held at a small venue near the frontline between the rebels at the Syrian national army and yet just under 100 people showed up and stayed until close to midnight watching the bands, Bashar recalled. His own band, Orion, performed their song Of Freedom and the Moor, as well as a cover of Sepultura’s Refuse/ Resist. Just outside the cafe was an abandoned, pock-marked car and four blocks away was the frontline. Even between the venue and the neighbourhoods where many of the fans still lived were dozens of checkpoints and the risk of sniper fire from the derelict high rise towers that once dominated what was Aleppo’s financial district was ever-present. Like everywhere else in Aleppo the venue itself, a former cafe, had no electricity or running water and the bands had to rely on generators to get the amplifiers and lights working. It regularly packed in, interrupting the music. “We had to run the whole gig on a small generator and there was no fuel,” Monzer recalled. “All of that, besides the war. Three of four sides are fighting in that area,” he said. The concert was held during the worst bombardment of Aleppo since the beginning of the war, on Christmas Eve 2013. Mere weeks earlier Assad had dropped barrel-bombs, improvised bombs created by cramming barrels full of explosives, on the east of the city and the rebels had promised ‘revenge’ on the regime held areas of Aleppo. In Monzer’s footage, the remaining metal fans in Aleppo are seen hunkered down in bedrooms, playing and recording music even as the shelling can be heard from nearby. In one poignant scene, Bashar guides Monzer round his house in Aleppo and the pair look in disbelief at the remnants of missiles that are scattered across his garden. Outside his front door, residents had hung bed-sheets between the trees to stop snipers taking pot shots at the few residents that remain. The footage cuts to Monzer and three other Syrian metallers walking through the shattered streets of what was once a thriving, liberal and developed city home to over 2,5 million people. There is an eerie silence as the pick their way through rubble as high as houses, with the spires of mosques and the metal pylons of high rise buildings protruding from beneath mountains of concrete. “Two years,” says one long-haired metaller, looking at the camera and holding up his index and middle finger to the camera: “All this in just two years.”

Monzer began documenting daily life for Syrian musicians in 2011 including his friends who were caught up in the fighting. He was on the way to interview a black metal musician from a village close to Hama when a suicide bomber struck the marketplace in the centre of town. “He ended up looking for his siblings amongst bodies. I was almost there. I was five minutes away,” Monzer said. His friend and others from the village armed themselves and have been protecting it ever since. It is not something that Monzer can fathom doing, but he understands his friend’s decision. “I cannot agree with any sort of fighting for anything. Or even the concept of guns. The idea is unpleasant for me just to think about,” he said. At one point during the film, he asks his friend whether he will ever put down his gun and pick up a guitar: “I don’t think it is time for guitars,” he says. But neither Monzer or Bashar agreed – for them, the shows were essential. “During these hard times you will die on the inside if you stop doing what you love. We lost our country but to preserve our souls we had to do what we loved,” Monzer said. “It is important during these hard times because this is what keeps you alive. This is how you can dream and be positive. How you can wake up in the morning and say we have something, we have this concert. I think it is hard for other people to see it like this but for people who were in the middle of it, during the worst times it was something that kept us alive.” But it was equally important to Monzer and Bashar to challenge the assumption that everyone in Syria is killing each other, he said. “I just wanted to document what was happening. That people during these hard times did not get violent, did not start to fight each other. At least my community – the metal community – was good” he said.

The last of Aleppo’s metal community scattered by the beginning of 2014. Bashar relocated to Latakia, where he opened the latest franchise of U-Ground Studios and tried to keep whatever was left of the scene alive in one of the few peaceful enclaves of Syria that was left. He never tried to get to Europe, or even to Beirut or Turkey, and when we spoke in 2016 was actually looking at the possibility of getting back to Aleppo rather than joining the 4.5 million Syrians that have fled the country. “I have plans here. I have already paid 15 years of my life I can’t just give it up and travel and start again – in somewhere I don’t know what will happen. I don’t want to leave my country in such a way,” he said. But even in Latakia, Bashar was finding organising gigs harder and harder, especially for extreme bands. He had started organising shows instead with rock and jazz cover bands, anyone who could play. Bashar was left rueing how different life could have been if the Syrian authorities had not carried out the crackdown in the late 2000s, if Syrian conservatives had realised that a bunch of guys making music and head-banging was no threat to their faith or their customs. He is tortured – even now – about what the Aleppo scene could have become: “The scene in Aleppo was big and it was growing. The only stopping us was the political and the police problem. We couldn’t just do what we want. But if we could have we would have been the number one genre of music in Syria. I assure you. The only problem that stopped the scene was the refusal, the denial of society and later from the police. If they had just said: go on, show us your best, we would have had great bands,” he said.

As for the war, Bashar saw parallels in how his community was treated by the authorities and the orgy of sectarian violence that the country has become. Syria turned on young men and women like Bashar, Monzer, Adel and Lyn. It excluded them, humiliated them, cast them out, called them satanists and devil worshippers, maligned their music and their passion. Bashar said that Syria was a divided nation long before 2011 and it was that refusal to accept people’s differences that resulted in the conflict today. Sunni versus Shia, Christians vs Kurds, what is that if not the hideously extreme logical extension of the repression that young metallers suffered at the hand of their neighbours and the authorities. “It had been growing for years, for decades, this hatred of the other,” he said. “And we musicians suffered from this hatred. So what about people who belongs to the different religions or places or ideologies? It had to happen because this society has to learn. They have to choose between living and killing each other.” When we met in Holland in 2016, I asked Adel Saflou when he became an atheist and he told me that it was when he was in exile in Beirut, near his university, when he heard the imam of a Sunni mosque giving a Friday sermon about the Christian festival of Easter. “He was saying not to congratulate Christians on Easter because it was against Islam. He said they were kuffars [unbelievers],” he recalled. The sermon not only disgusted Adel because it was hateful, but because it was just kind of language that had been used to justify the years of hate and repression, the beatings and the arrests, that had been meted out if not to him, then to his friends. “I thought: this is where the hate starts,” he said. “This is where all the terrible shit in my life starts.”

For Monzer, that hatred did not stop when they left Syria. He moved to Algeria first, where he worked for six months for a graphic design company. When his contract ended his boss refused to pay him and so he returned to Beirut with nothing. He went to Turkey but in Istanbul found that Turkish landlords would refuse to rent to Syrians and even when Monzer managed to get a friend to help him negotiate he was only allowed to stay for three months at a time. Given that he had no rental contract, he could not get connected to utilities and had to live without water. He noticed a change in attitudes in Turkey towards Syrians as right wing anti-Syrian parties grew in popularity. In his neighbourhood in Istanbul he would see racist graffiti every day. “It wasn’t the perfect environment to think about starting again – this is when I decided to go to Europe,” he said. Lyn, who had been living in Latakia, met Monzer in Turkey and they began preparing to make the crossing to Greece through the people smuggling gangs who openly ply their trade on the streets of Istanbul. Monzer and Lyn, who had little exposure to the world of organised crime during their lives in Syria, were suddenly thrust into a world of shady characters and dodgy dealings, but it was their only hope of starting again. “You’re in survivor mode. You have this huge dream in your head. I think this is what moved me. I thought that when I finally arrive in Europe things would be positive again That life would be fair with me for once,” said Monzer.

A few weeks later they packed into a flimsy rubber boat with four dozen other desperate Syrians and crossed the Mediterranean on a flimsy rubber boat. On the beach, the smugglers ordered the couple to sit on opposite sides of the boat, so as they were thrown around in the open sea they could not even see each other. When the boat finally reached Greece, they remained on the beach helping the other refugees register with the Greek authorities. They were still dressed in their waterproof clothes and coats and looked like any other Syrian that had made the perilous crossing. They walked with the families and others that they had helped to the camp, where they changed into their regular clothes. It was then that the friendliness of their fellow refugees evaporated. “When they saw Lyn wearing shorts they said we were infidels, and they stopped talking to us,” Monzer said: “This is the first thing that happened to me in Europe.” The discrimination that he and Lyn had faced in Syria had followed him to Greece – they were refugees not just in Europe but amongst their own people. It followed them again to Holland, where they flew after buying fake Spanish passports in Athens. As part of their asylum process, they were expected to attend classes to help the adjust to life in Europe. When they went to the university they found themselves surrounded by conservative families similar to those they had met on the beach in Greece. Monzer almost came to blows with a man in one session who argued that it wasn’t right for women to be educated, as Lyn sat a few desks away. In other classes, Monzer said that Dutch tutors would caution him that in Holland it was not acceptable to beat your wife – as if he ever had, or would. “You ask yourself: ‘Why have we risked our lives?’ Because we almost drowned in the Mediterranean. It was terrifying. And after all that when you end up in the place you have always dreamed about, everyone thinks that you’re violent or that you are not tolerant or that you beat your wife. That you’re a radical, or your ignorant or you have never seen the TV or the internet. All of that combined: it doesn’t help you stay the happy person you were once. In the middle of the war I was more positive than I am today,” Monzer said.

Holed up in their flat in Naarden, Monzer and Lyn seem almost nostalgic for Syria even in the early days of the war. Monzer speaks of his hometown – of the restaurants and the bars on the three mountains that surround it, of the cafes that are always open and the shops that never close, of the warmth and the friendliness of the people there. He and Lyn are so grateful for the sanctuary that Europe has given them, but Syria burns brightly in their hearts despite everything: “We dream of going back. We talk about going back everyday if things get better. Whenever we call someone and tell them they are like, no you’re crazy, why would you leave safety and all of that to get back? But I think it is about the small details: it is about your neighbours, and your friends. It’s about being in a friendly environment. Everything else you can get used to: new places, new views, new streets – these are objects. But when it comes to actions, the way people see you. You start thinking have I done the right thing, have I risked my life for the right thing,” he said.

When he thinks about returning, the one thing that crosses his mind is: would things be different. In the early days of the war, Bashar and Monzer could arrange shows in Latakia and Aleppo and nobody seemed to care. Would the arrests and the accusations be a thing of the past in New Syria? The thought is a tantalising one for Monzer and Lyn, holed up on their battered couch in an empty room watching footage from Syria and another lifetime. “One day, can we get back – all of us – and do our thing. Will they accept us? Because here we can do whatever the hell we want. If we get back and wanted to do something, a concert, and we weren’t accepted, that would be a huge disappointment,” he said.

Those who didn’t make it to Europe have joined 4.5 million Syrians that have fled their homes for Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon, the latter of which was in 2016 home to 1.7 million refugees from Syria alone. When I visited Beirut in the summer of 2016, the city was packed with refugees, many of which would beg for change with the expatriates and wealthy Lebanese that frequent the bars and cafes of Germaze, in the city’s Christian east. In the Bekaa Valley, the fertile valley that joins Lebanon and Syria, every vacant patch of land was taken up with tents as tens of thousands of Syrians eked out a meagre existence working in farming or construction. On a construction site just seven kilometres from the Syrian border, Lebanese workers spoke of their frustration with hundreds of thousands of Syrians who had made Lebanon their home since 2012, commenting that the influx of cheap labour was hitting their jobs and salaries. The Lebanese government, which closed the border in 2015, had begun arresting Syrians who were not permitted to be in the country and while there are no reports of refugees actually being deported – which would be in contravention of Lebanon’s international obligations – conditions were deteriorating.

It hasn’t all been villagers and farm workers that have migrated to Lebanon as the war wages in Syria however, but bands too. When Adel Saflou was in Lebanon in 2014 and 2015, he spoke of a thriving Syrian rock and metal scene with rock and indie bands such as Tanjaret Daghet and Khebez Dawle – now in Berlin – alongside Syrian metal bands such as the Hourglass. I met Tanjaret Daghet in June 2016 in a cafe close to their recording studio in Beirut’s al-Hamra district. Founded in Damascus in 2012, the Syrian three piece were being spoken of as one of the hottest bands – Syrian or otherwise – on the Beirut scene since moving to Lebanon at the end of 2011. They have recorded their debut album and featured in newspapers and magazines throughout the world, largely alongside headlines relating to the Syrian conflict and the disbelief that a group of musicians from such a troubled part of the world can make a success of themselves. It is an angle that Tarek Ziad Khuluki, the band’s guitarist, clearly resented.

“It is a kind of a way for the media to reach more people, from what a big story it is now. It is opportunistic,” said Tarek. Putting on a mock sympathetic voice, he said: “The media is going, you know: ‘Syrians, you know, they are fucked up.’ The other members of the band nodded: “It is about us,” Khaled Omran, the band’s bassist, added.

Dani Shukri was the vocalist in a death metal band before meeting Khaled and Tarek in 2008. They founded Tanjaret Daghet and had their first gig the following year. The band are a mish-mash of influences, from Danny’s background in death metal to Khaled’s passion for orchestral music. When asked about influences, the three young men throw in everything from Jack White to Shostakovich and their music is a fusion of rock, grunge and indie and Arabic music. Their desire to play their own music as a young band in Damascus had them run up against similar issues as the metal crowd, in that most fans wanted to hear covers. “The young generation expected the local bands to give them the opportunity to listen to their favourite songs. If you play a Metallica song you have to play it as Metallica played it,” Dani said. “Then if you wanted to make it you had to play the solo exactly as it was played – if you put your own take on it, it would be seen as you not being good enough to play it the right way,” added Tarek.

A small group of bands in Damascus would rent small cafes and cinemas to organise gigs, but the crowds remained small. I don’t want to say this type of music was not welcome, but it was not something that people really wanted to hear. It was more our age generation. It was the shit that we used to listen to,” said Tarek. When he first talked about leaving Syria, his brother encouraged him to take a job washing dishes at a friend’s restaurant in Belarus. He gave Tarek an ultimatum – he could move to Eastern Europe with the promise of a steady job and security, or he could go to Beirut with the band – but he would do it without his family’s support. Tarek chose the latter. This was 2011, when many Syrians who could afford to were already looking overseas for opportunities as the revolution progressed. But for Tanjaret Daghet there was nothing political about their move to Beirut – it was practical. “If you want to write your own material in Syria there was only one or two studios [nearby]: here in Hamra you can find four or five studios. This is what is good about Beirut. It has this pulse. There it is more small, closed,” he said.

Even though they are already a success in Beirut, the band are still thinking bigger. They say that while the crowds are better in Lebanon, where they really want to be is Europe, where you can play to 5,000 or 10,000 festival crowds and the competition is tight. But above all, they want to surpass their current status as a Syrian band. All three are sick of being asked about Syria, about the conflict and whether it has changed them or their music. Tarek gets angry when asked about Syria: “If you want to know the news I can give you now like ten channels and you can see what is happening to my country,” he said.

“As soon as we left Syria we knew it might take a long time to go back. So what it did was it meant that you don’t have a comfort zone. It put us in a situation where we want to keep moving and not consider any place to be like: this is my home,” added Dani. “It changes the way you live, the way you deal with things – and your music.” Tarek is sceptical of bands from Syria that have made the war and the revolution so central to their message. He wants Tanjaret Daghet to surpass it. “All the people who are singing about just the war today I am really wondering what kind of idea they will come up with after the war is over. What are they going to talk about then?” he said.

As Adel sat amidst the chaos of the boat listening to Somewhere Over the Rainbow, the thought crossed his mind that this was how it would end. During 2015, 3,771 migrants drowned in the Mediterranean and there was no good reason why he wasn’t 3,772. It was dark, around 2 am, when he managed to get hold of the coastguard and they said help was on its way but it was another six hours before they heard the whirring of the helicopter above their heads. They were rescued in small groups before being taken to Samors and then to Athens, where Adel and his cousins walked to Austria via Macedonia, Serbia and Hungary. By the time we met in Almelo, Holland, in the summer of 2016, Adel was living in a single room in an asylum centre on the outskirts of the town, surrounded by green fields and cows and quaint little Dutch houses. The centre was a shabby selection of pre-fabricated two-storey buildings and Adel’s neighbours, mostly Syrian families, eyed him curiously with his piercings and tattoos – but it was safe and warm and he could come and go as he pleased. Since first arriving in Holland he had seen the inside of nine different asylum centres, one which was actually a maximum security prison. His cousins have been housed elsewhere in Holland and he sees them from time to time. When he looks at them sitting around with their kids running around oblivious, he remembers how he strapped on their life jackets on the beach in Izmir and wondered whether they would survive the night. “I don’t know how we made it. I look at my cousins now, and think: how can we do that? How can we joke about it now?” he said. “I don’t believe in miracles but it was. It was a miracle of human deed.”

Adel had spent the first two years of his life as a refugee in Lebanon, first near Tripoli, north of Beirut, where he studied mass communication at university before being kicked out for possession of cannabis. He was jailed for a month and the government took away his student residents permit and, like many Syrians who had crossed the border to Lebanon, he melted into the huge refugee population in Beirut. It is often forgotten in the media scare stories about refugee ‘swarms in Europe’ but Turkey, Jordan and Lebanon combined were hosting 4.5 million displaced Syrians by 2016 – 1.7 million of them in Lebanon alone. When I visited Beirut in the summer of 2016, the city was packed with refugees, many of which would beg for change with the expatriates and wealthy Lebanese that frequent the bars and cafes of Germaze, in the city’s Christian east. Adel was sent money regularly by his father, who lives in the UK, and relied on a support network of friends and musicians from Aleppo and elsewhere in Syria: “I laid low for like a year and a half. My dad was sending me money and I just sat there and recorded an album,” he said.

The album was recorded under the name of Adel’s solo project, Ambrotype, and was a concept album based on the tyrannical rule of an immortal despot (a thinly-veiled attack on Bashar al-Assad and the Syrian regime). It dealt with Syria, his home, and drew on his proximity to Syrian musicians and bands that he still hung out with Beirut. By the time we meet in Holland in 2016, only a year has passed and already the album feels outdated, he said. His voyage from Izmir to Samos, from Athens through Macedonia to Austria and now to Holland, has changed him as a person and as a musician. Adel’s music is no longer about Syria – about his old life, a world that no longer exists and maybe never will again – it is about exile.“my journey has made me a different person. I am not what I was a year ago, not even close. I have a different view on life. I don’t know what I am. I am lost. Having to be here. Having to be in extreme exodus. It is terrible,” he said. “I think: why am I like this? Why am I not a rich guy who plays golf and claps like this,” he said, clapping his hands together in an effete gesture of applause.

I asked him what he would do if the conflict was solved, if there was peace and the cities that he grew up were restored. “Solved?,” he asked, incredulous. “If the war was solved? Everyone that I know is fucked up, everyone I knew, every person I loved is really deeply scared. If all of them – all of these people – were healed and they went back to Syria and we got back to the old days when we just finished a concert and we went to my friends house and we got drunk until the morning and we pissed on his mother’s plants – of course I would go, I would love to. It was the best time of my life. There’s nothing more I look back to than this. The life with friends. Such a life such a normal life with people who actually accept you. People who actually think this is home,” he said. He, like Monzer and Lyn, has found Europe a disappointment. He had long worshipped the bands that came from Europe and had idealistic views of the scene here, but when he attended a concert and saw big name international bands play one after another on huge stages in front of tens of thousands of people it wasn’t that he was underwhelmed with the music – quite the opposite – but that the crowd wasn’t overwhelmed. He had sat at home in Idlib and learned everything he could about bands like Opeth – he worshipped them – but in Europe, metal fans took the access they had to this music for granted. He resented it. But it wasn’t just that – he thought it would be easy to make friends in the metal scene in Europe, even in his isolation in Almelo, but it has been far more difficult than he expected. “European people are colder. This is not necessarily a bad thing, but everything is different from what I am used to. The friendship bonds are culturally different. It is a subconscious barrier. I find a lot of nice people here but it is never the same as your old buddies getting together and everyone really knows who you are – really knows who you are,” he said. “Like here, no-one knows who you are and no-one cares. Here you are just a number: a refugee.”

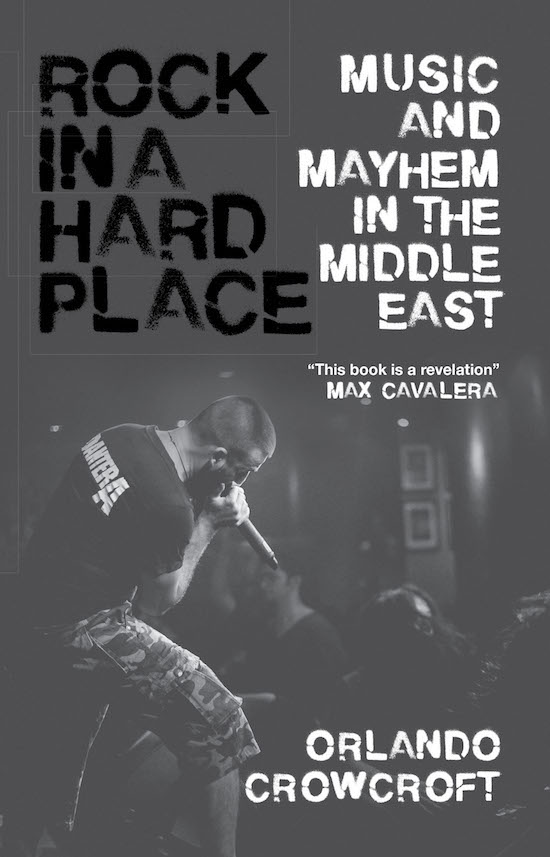

Rock In A Hard Place: Music And Mayhem In The Middle East is out now on Zed Books