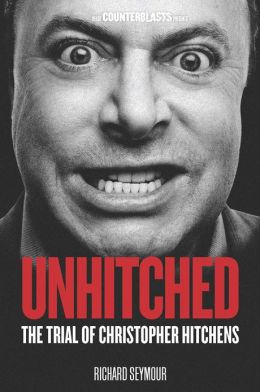

Whether or not you have read many – or indeed any – of the late Christopher Hitchens’ books or magazine articles, if you’re reading this review, it’s probable that you at least know who he was. You’re probably dimly aware of his status as a sort of turncoat leftist who threw his support behind George W Bush’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. You may even have been on a little YouTube odyssey of clips of his put-downs and confrontations in debates and interviews. Or you may be a fully paid-up member of his fan club. The man certainly made some waves; what you may have thought of those waves is another matter. By the end of his book Unhitched: The Trial of Christopher Hitchens, we are left in no doubt as to what Richard Seymour thinks of them.

With the kind of relentless zeal that is, funnily enough, characteristic of the man himself, Seymour attempts to rip apart Hitchens’ politics and expose him as a self-serving hypocrite – capable of taking up practically any position which might advance his own career, whilst simultaneously lying about how he arrived at it in order to preserve a semblance of integrity. Seymour is not unsuccessful in his endeavour, it must be said – the book is vigorously researched and Seymour is able to expose the many holes and flaws in Hitch’s politics with some precision – but it begs the question of why he thought it would make a necessary or enjoyable read.

Seymour’s thinking is that Hitchens represents an interesting case study: ‘Leftists often become ex-leftists at the moment they perceive the militarised nation-state as the appropriate defender of progress or democracy,’ he contends in his prologue, listing John Spargo, Max Eastman, James Burnham and Irving Kristol as similar examples. This contention is certainly borne out by the evidence of Hitchens’ political development which he presents. But what exactly is the reader supposed to gain from this knowledge of a leftist defector? It is a question Seymour doesn’t attempt to answer, preferring instead to nit-pick his way through the various glaring inconsistencies of Hitchens’ arguments. One of the problems with this is that, whilst he is able to make a strong case against Hitchens being a serious thinker, he is not really telling us anything we did not already know. Hitchens was notorious for being a contrarian, for enjoying an argument, causing a stir, and for many people this was his charm. He was not necessarily revered for the consistency of his political approach – something that has been questioned in print many (many) times before.

Unfortunately for Seymour, his book is perhaps most interesting in ways he does not intend it to be. Seymour states: ‘This is not a biography but an extended political essay’ and yet his continuous refutations of the bases for Hitchens’ politics become so tiresome that, even if they are accurately argued, we become more interested in the the background information he provides about Hitch and his transition from left to right than in his exposure of the faults of his convictions. One of the more interesting passages in the book is, for instance, that in which Seymour examines in some detail Hitchens’ relationship to Thatcherism: however, this examination is cut short and rounded off by linking his closet Thatcherism to his latter-day imperialist tendencies and an Islamophobic article he wrote about the number of Algerians in Finsbury Park. One cannot help thinking that a biography, albeit a highly critical one, might have been a more interesting enterprise.

By the end of Unhitched there is the sense that Seymour is doing nothing more than continually wagging his finger and saying “See! You see what happens when you turn against us?” You get a fairly dull book written about you might be the answer.

Unhitched: The Trial of Christopher Hitchens is available now, published by Verso Books

Follow @theQuietusBooks on Twitter for more