There is no such thing as an aspiring writer: you’re either writing or you’re not. Richard Milward sat down at home in Middlesbrough with a pencil and paper aged 12, immediately after devouring Trainspotting in the Britpop-soundtracked summer of 1996, and hasn’t had a month off since. He’d already produced half-a-dozen novels before one of them, a tale of acid-gobbling teenage mums titled Apples, was published in 2007. His second, Ten Storey Love Song, followed in 2009. Written as a single pill-fuelled paragraph, the unbroken text mimics the novel’s tower-block setting, where lives intertwine and interrupt each other at will.

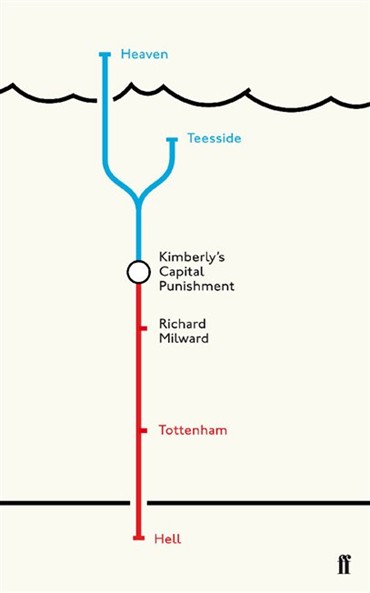

His new book, Kimberly’s Capital Punishment, is a sprawling epic which pushes the formal inventiveness still further: there are multiple endings, the dialogue of inseparable mates Shaun and Sean is rendered as parallel columns and the words from a memorised menu form the shape of a stag’s head on the page. That’s just the start of it, but Milward’s experimentation is always in service of his narrative. Here, he discusses death, drugs and the strange rituals of writing.

Where did the first germ of an idea for Kimberly’s Capital Punishment come from?

Richard Millward: The first idea that I came up with was having multiple endings. I liked the idea of, halfway through the story, bumping off the character and getting the reader to roll that dice to see what happens to her in the afterlife. I wanted the story to be conceptually sound: with humans, we all know we’re going to pop our clogs at some point but no one knows what’s going to happen after the last gasp. I thought, why not give the reader six possible options?

So you knew you wanted to tackle mortality?

RM: Yeah, but I thought it might be a bit of a risk basing a whole book around the morbid fear of death – so I tried to turn it into a jet-black comedy. The book juggles hilarity and horror. I do seem to like focusing in on a big theme for each book: dead loosely, I’d say my first book Apples was about sex, Ten Storey Love Song was about drugs and this one’s all about death.

And that morbid, life-shaking fear that comes from contemplating your own mortality is present just below the surface of the book…

RM: Yeah, definitely. It still happens today, and I’m sure everyone goes through these periods, but when I was younger I’d be in bed or something and absolutely frightened to death. Realising that you’re actually mortal and at some point you’re going to die is such a frightening thought, but everyone has those feelings at some point. With the idea of the afterlife it was nice to use so much artistic licence in depicting scenes in heaven and hell. It was quite liberating, not in the sense that writing this novel has helped me come to terms with the fact of my own mortality at all, but it’s definitely been entertaining trying to piece it all together and ponder what might be waiting for us behind the final curtain.

The multiple endings are just one of the novel’s formal experiments. Where did they come from?

RM: A lot of my favourite writers are experimental writers – William Burroughs or surrealists like the OULIPO group who experimented a lot with the way text looks on the page – I wanted the book to be a celebration of that. I use Burroughsian cut-ups throughout and there are acrostics and things like that. I love Vladimir Nabokov as well, and the way that he puts little puzzles in his novels. Pale Fire is such a genius book; it almost reminds me of a David Lynch film. There’s three different branches to the story and you could probably spend years analysing that book just trying to figure out who the hell the first-person narrator is. I’m not saying my puzzles are as good as Nabokov’s, because he’s a genius, but I love setting up layers of intrigue. People might not notice the little secret symbols, but I think the novel probably works better if you keep your eyes wide open. That’s why I wanted the eyeball to begin the book: in a sense it could be the reader’s eyeball. It’s never specifically stated that it’s Stevie’s eyeball that she comes across at the beginning. There is that sense that the reader has got to be on their toes at all times.

So, when did you start writing?

RM: The book that set me off was Trainspotting. I was 11 or 12 when that came out. All of British culture then was so inspiring for a 12 year old lad. There was Britpop, British artists and all these Scottish writers who seemed really innovative with language and subject matter. The thing about Trainspotting was that I was only 12 and wasn’t allowed to go to the cinema to see it because it’s an 18. I had to twist my mam’s arm to get me the book. She looked at it in the bookshop and lo and behold the first page she came across was the chapter entitled ‘Cock Problems’, where Renton’s having a little bit of trouble finding an inlet in his cock. That didn’t bode too well for my mam, but I persuaded her to buy it for me and it just opened my eyes up to what literature could be. When you’re 12 teachers are trying to force feed you Point Horror novels, or for the girls it’s Sweet Valley High. It didn’t seem relevant to anything that was going on in Britain. Picking up Trainspotting for the first time seemed like something very special.

And you started writing your own stories straight away?

RM: Yeah, I’d say Apples was maybe the seventh book I’d written, but I’d been pestering publishers about my earlier stuff too. To start off with it was just a case of ripping off all the literature that I loved. It’s been a learning curve for me, trying to teach myself how to write, probably making a lot of mistakes along the way. Not to slag off people who’ve been through creative writing courses, but when I read contemporary writing it does seem like even the language used is quite samey, like they’ve been churned off a conveyor belt. At least by teaching myself I’ve got my own distinct voice – even if it has a few holes in it.

I don’t have the ghost of a tutor sitting behind me while I’m writing. I don’t analyse it in terms of needing to put in metaphors or similes in certain places. I pretty much just bombard my writing with metaphors anyway. It’s nice not to adhere to a rulebook. Musicians don’t have to have read music. You can just attack it with the abandon of a child.

At what point did it hit you that you’d turned pro?

RM: The strangest thing about being a fulltime writer now is that you do get reviews. I’ve been through a decade of writing and not showing anyone and not getting any feedback except for what I was giving myself. Now I do get analysed, not that that makes me self-conscious or want to pander to what a critic thinks are my weak spots. All that matters is that hopefully if people have the same taste as me then they’ll enjoy my books.

So, you don’t feel under pressure?

RM: I try to write stuff that I would find entertaining; there isn’t much pressure in that – only from myself. I am really self-critical, just from wanting to get better and better. I don’t feel under pressure from the press, but it was quite strange when Apples came out. The press were quick to label me as the “voice of youth” and were lumping me in with MySpace and Facebook as if I was the “voice of Facebook”, but I don’t want anything to do with social networking. I’m fully aware that I’m a work-in-progress myself, so I just want to keep pushing myself and make the language as beautiful as possible and make my plots better all the time.

Maybe they’re not the voice of Facebook, but who do you read of your contemporaries?

RM: I love Joe Dunthorne, who wrote Submarine. He effortlessly punches up these beautiful sentences with a sense of humour. Joe Stretch’s first two books are these nightmarish satires which really do the trick. I love a writer called Michael Smith, who’s considered the Hunter S Thompson of Hartlepool; he’s got a book called The Giro Playboy which is just these little vignettes of his life in London, Hartlepool and Brighton. Like Kerouac, they’re about the poetry of everyday life.

How much have drugs influenced your writing?

RM: In all my writing I do try to blur the boundary between dream and reality, in the way that writers like Hunter Thompson do; drugs are a chemical way of achieving that. When I started taking ecstasy or magic mushrooms they almost proved a lot of the things I was thinking anyway. But I’m inspired a lot by my dreams. The surrealists weren’t a drugged up group of artists, Salvador Dali famously said: “I’m not on drugs, I am drugs.” I’ve always been inspired by their experiments with dreams and the unconscious, and it seems like drugs are a fast-track to get into that same mindset.

But drugs don’t get the writing done…

RM: Yeah, it’s tough. It’s really counter-productive taking drugs in the sense that you feel terrible the morning after. Nobody’s in the mood to pick up the pen and write Shakespeare when they’ve got a massive hangover or a come down. Drugs can be a catalyst for inspiration, but it’s not going to be workable to just smash a load of drugs and then carve yourself a career in writing. When you’re high as a kite the last thing you want to do is pick up a pencil and write this horrible, affected, garbled drug writing.

And there aren’t many things more boring than people telling you about the funny thing that happened to them when they were high…

RM: Exactly. I’ve come across a lot of people who’ve read Apples or Ten Storey Love Song who’ll say to me: “Oh, that’s nothing compared to what I’ve done!” As if it’s a competition and I’ve written it just to show people that I’ve done drugs once in my life. It’s weird when people tell me that what they’d write would be ten times madder. The writing might not quite be up to scratch.

Is that what sets someone like Hunter Thompson apart for you?

RM: What I find interesting about his Gonzo journalism is the way he plays with dream and reality. When you think about it, every story people tell isn’t specifically based in fact. Hunter wasn’t sure whether the public expected him to really be Raoul Duke. I’m fully aware that even when you hear conversations in pubs it’s impossible to pin down pure reality. Hunter Thompson blurs that distinction between reality and dreams with aplomb.

Are you good at holding court in a pub yourself?

RM: Not at all. I have trouble verbalising my thoughts. I’m not sure if most writers are like that. It’s such a solitary existence, where you can take a lot more care and time over expressing something in writing. I’m a good listener, and that helps with the writing. A lot of my friends are big, strong, bold characters themselves, and there’s nothing better than just sitting in the pub and listening to all these daft anecdotes getting batted back and forth across the table. It’s nice to soak that stuff up, possibly to use as inspiration but otherwise to just enjoy it for what it is.

Do you listen to music when you write?

RM: Yeah, I have some quite strange rituals. I have to wash my hands four or five times before I get down to business. I do listen to music but it’s at volume one. (My hi-fi goes up to one hundred.) It’s barely audible – I think you’re more critical of yourself in a silent room. It at least covers up the rest of the world. Even at volume one it drowns out stuff happening outside or in the flats next door.

It can seem tomb-like if you’re sat in a silent room. It’s such a solitary experience. It’s also a mark of time. I only listen to albums that are more than 50 minutes long, so at least I have a sense of time passing. If I wrote in silence I’d probably sit there writing for four or five minutes and feel like I’d done two hours work.

What do you listen to?

RM: I love Sonic Youth and The Fall. I’m a big fan of Mark E Smith but it’s quite a difficult one to listen to while writing because it’s too tempting to rip off some of his terms and his brilliant lyricism. I just listen to strange guitar music. I love My Bloody Valentine, because it’s about the guitar textures and they shovel shed-loads of distortion over the lyrics anyway. It seems to work better listening to something a bit more dreamlike.

When you’ve got your hands clean and your music barely audible, how do you go about writing – how does the physical process fit in with that mythology?

RM: I do my first drafts with paper and pencil. There’s something quite cold about starting working on a laptop, just the look of it with the annotations that you get when you’re trying to write something on Microsoft Word. It looks straight and clinical. Once I move onto a laptop I tend to print everything off and scribble on it again with a pen. When it’s pencil and paper you can rub things out or cross them out, but you’ve only got a certain amount of space to make your mistakes in. It also encourages you to rewrite from scratch. On the laptop you can cut and paste or delete little lines, but on paper if it looks like a mess you have to write it out again from start to finish.

And are you working on your next book now?

RM: Yeah, when I finish a book I always have ideas for the next one. It’s quite early days with this one, but I’ve been really inspired by amateur boxing. I’ve interviewed everyone from 9-year-old pugilists to our Olympic gold medallist Luke Campbell, but I’m definitely not going to be writing Rocky. I’m intrigued by the sacrifices that these young boys make, giving up fast food, intoxicants and girls, sometimes. People tar boxers with the idea that they’re aggressive brutes, and imagine they might fight on the streets, but it’s such a disciplined sport. The lads you meet at the clubs are really humble and determined. Writing literature can seem like an ignoble profession when you see these kids who are so determined to do this really pure sport.