Gaye Bykers On Acid, photo by Phil Nicholls

The mid-80s in Britain was not a great time for rock music. The excitement of the NWOBHM had long since burnt out, neo-prog had merely succeeded in producing Marillion’s mawkish ‘Kayleigh’, and first-wave goth had crashed with the apparent dissolution of the Sisters Of Mercy. The indie scene was increasingly inward-looking and parochial, feyly jingle-jangling or mumbling in a void, and the mainstream was caught in the toxic vapour trail of Live Aid and the ‘rock royalty’ it had helped to create: Queen, U2, Dire Straits et al… Believe me, I was there, and it was boring as hell.

But as is always the case, a new noise was bubbling up to fill the vacuum, a “burst of dirty thunder” as it was subsequently described. The very name of this ‘scene’ still invites derision, but Rich Deakin – author of the excellent Deviants and Pink Fairies’ history Keep It Together! – has grasped the nettle and written Grebo! The Loud And Lousy Story Of Gaye Bykers On Acid And Crazyhead, which celebrates two of the bands who kicked against this state of mundanity and attempted to inject some fun and excitement back into the British music scene.

Gaye Bykers On Acid and Crazyhead both came from Leicester, and had grown up together in the same pubs and clubs, but other than a shared love of making a racket, they didn’t actually sound that much alike. GBOA had the more ridiculous name, were pathological piss-takers, and plied a pop/punk take on the space rock of Hawkwind and the hallucinogenic post-hardcore of Butthole Surfers; Crazyhead combined the high energy attack of Motörhead and The Stooges with the rough melodic nous of the classic Nuggets garage bands.

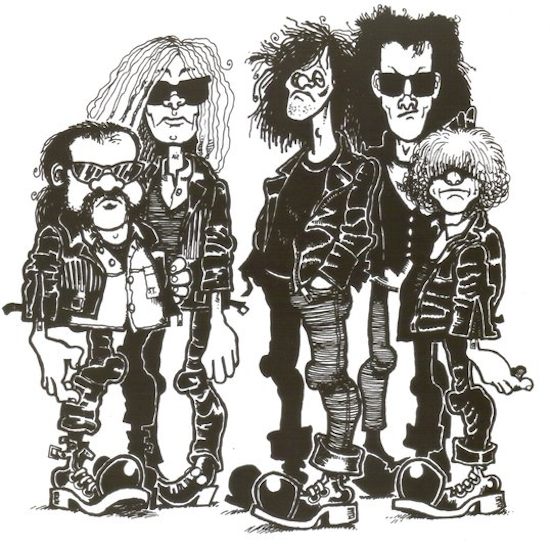

However, they had plenty of other things in common. For a start, they both looked like proper bands. The Bykers favoured a thrift store Mad Max look, fatigued multicoloured threads and crappy dreadlocks, while Crazyhead adopted a more traditional leathers and black jeans image. And there was something wonderfully cartoonish about them at a time when comics were breaking big – 2000AD was at its peak, with spin-offs Crisis and Deadline just around the corner, Alan Moore had emerged as a graphic novel guru, and practically everyone read Viz (a Simon Thorp caricature of Crazyhead even featured in its hallowed pages). Oh, and they were both fantastic live.

The two bands burnt brightly for eighteen months or so, each releasing a couple of tremendous, indie chart-busting singles while gazing out from the front covers of the music press. Yet their reversal of fortune was swift and harsh. Undergoing trial by major label, both delivered over-produced, underwhelming debut albums, and the press moved on with indecent haste.

Crazyhead cartoon by Simon Thorp

But they deserve to be remembered for those singles alone: for GBOA, the wired psychedelic stomp of ‘Everythang’s Groovy’ and the shouty electro punk of ‘Nosedive Karma’ (and its brilliant B-side ‘Delirium’); for Crazyhead, the brain-pummelling rush of ‘What Gives You The Idea That You’re So Amazing Baby?’ and the acerbic rockabilly of ‘Baby Turpentine’ (which features another great B-side, a cover of Sonny & Cher’s ‘Bang Bang’).

I spoke to Rich Deakin and got the whole loud and lousy story…

Can you remember what your initial impressions of both bands were?

I first saw the Bykers in January 1987, not long after their debut single had been released. They were a monstrous wall of thunderous rama-lama rifferama and wah-drenched sonic mayhem – an unholy amalgam of the MC5 and Stooges colliding head on with Jimi Hendrix, the Sex Pistols, and Hawkwind.

Similarly, Crazyhead just exuded attitude and swagger live, their whole look a mutant cross between Don’t Look Back-era Bob Dylan and Johnny Rotten circa San Francisco Winterland, with a gob of biker chic thrown in for good measure. Their sped-up 60s garage rock sound combined with a punk energy and aggression appealed to me in spades.

It seemed to be deliberately ugly in some ways, a reaction against the conservatism of the mid-80s British indie scene…

I don’t know if it was deliberately or just naturally ugly, but it was colourful too, albeit day-glo garish, with customised spray-painted equipment and clothing. You’ve got to remember ‘grebo’ was a fairly broad umbrella, and the press lumped all manner of different bands under it, from the Bykers, Crazyhead, and Pop Will Eat Itself to Zodiac Mindwarp & The Love Reaction and even The Cult.

Not everyone was into the dour miserabilism of Morrissey and The Smiths, or the twee, jangly pop of the C86 indie scene. As far I was concerned, the bands that were labelled as grebos, including the Bykers and Crazyhead, were an antidote to not only the above, but also the mainstream charts, which were awash with the manufactured pop pulp being churned out of the Stock Aitken & Waterman hit factory. They also provided a more brutal looking and sounding alternative to the Spandex-trousered, poodle-haired cock rockers that were in vogue at the time.

Crucially, grebo wasn’t a London-based scene…

Grebo was largely perceived to be and portrayed as a provincial phenomenon with its epicentre being the Midlands – whether it was Stourbridge in the West Midlands, as in the case of Pop Will Eat Itself, and slightly later The Wonder Stuff and Ned’s Atomic Dustbin, or Leicester in the East Midlands, as exemplified by not only Gaye Bykers On Acid and Crazyhead, but also The Bomb Party, The Hunters Club and Scum Pups.

James Brown, who went on to found Loaded magazine, is credited with having ‘invented’ the grebo scene – it might have helped the bands in the short-term, but it comes over as rather a patronising and cynical move…

Yes, but hasn’t this always been the case in music journalism? Grebo propelled bands like the Bykers, Crazyhead and Pop Will Eat Itself into the media spotlight and onto the covers of NME, Sounds and Melody Maker. You just couldn’t buy publicity like that.

James Brown told me, “They were very easy to write about and it was a change from other bands who were intent on creating perfect pop songs. Simply because of their hair length, lack of stylistic pretension and roughly similar geographic locations – the Midlands – it was easy to put the Bykers, the Poppies, and Crazyhead into one group and call them a ‘grebo’ scene. I’d never even heard that term before hearing it in the titles of two Poppies songs. I knew there weren’t huge gangs of grebos roaming the land like mods, punks, and rockers did when I was at school in the late 70s, but it gave me something fun to write about. My freelance colleagues and I at Sounds were skint young writers trying to make a living, and ‘inventing’ a scene, as I was accused of, was just another way of getting to write more about bands we liked.”

Crazyhead in particular seemed to be unhappy with the grebo tag at the time, and some band members are still unhappy with it today. They realise it provided them with a huge amount of publicity they might not have received otherwise, but it did them harm going forward too. But whether they like it or not, both bands will forever be associated with the genre, and not just because of this book’s title!

Ironically, Pop Will Eat Itself, the band that unwittingly gave the genre its name in the first place, seemed to shed the negative connotations associated with grebo much easier than their Leicester counterparts, and in the process went on to achieve success throughout the 90s.

Gaye Bykers On Acid cartoon by Jon Langford

GBOA’s use of sampling and hip hop beats, and their desire to make films and be a multimedia unit, was quite ahead of its time…

Yes, the Bykers and Pop Will Eat Itself had already begun experimenting with sounds that some industrial bands only started doing later with programmed beats and guitar riffs, and arguably pre-empted the dance rock fusion of the Madchester scene, or evolved in parallel to it. By the time the Bykers split in 1990, they had embraced techno and rave culture wholeheartedly. You only need to check out the S.P.A.C.E. EP released under their PFX pseudonym, or their last album Pernicious Nonsense, to see the route they were tripping down.

Despite their reputation, and contrary to what many people believed, the Bykers were extremely hard-working and very driven. They had a strong DIY ethic before they signed to Virgin, and again after when they set up their own Naked Brain record label.

It seems slightly incredible that Virgin let them make a feature length promo film with their advance when they were meant to be making their debut album…

Maybe so, but even before they signed to Virgin, the movie had always been part of the Bykers’ masterplan. There were several majors sniffing around them, and Virgin, perhaps keen not to miss out on signing what was being feted as this next big thing readily agreed to their demands. I seem to recall Mary Byker, or maybe it was Robber, telling me they convinced Virgin they could make a promo film for the whole album for less than it would cost to make a video for a Boy George single.

The Bykers’ feet never touched the ground for much of that year, and they took their eye off the ball as far as Alex Fergusson’s production of the Drill Your Own Hole album was concerned. That said, I think the album stands the test of time better than its critics suggest.

The story of Crazyhead’s role as unlikely cultural ambassadors following the collapse of the Soviet Union is a surprisingly emotional one…

The British Council were behind a number of overseas gigs featuring British bands and musicians with the intention of promoting harmonious relations between nations. During 1989 and 1990, Crazyhead played at several events in Russia, Romania, and the newly independent Namibia. In February 1990, barely two months after the Ceaușescu dictatorship had been toppled, they visited Romania with two other British bands, Jesus Jones and Skin Games. The horrors of the regime were still evident everywhere, and the band met surviving families of some of the victims in Timisoara.

The performances were emotionally charged affairs, not through shock or horror, but more through elation at seeing so many people who had been under the yoke of communist repression for so long tasting freedom, and local bands being able to sing in English for the first time in over a decade after it had been banned by the regime. They elicited a rapturous response everywhere from the adopted anthem of the tour, a rousing cover version of Neil Young’s ‘Rockin’ In The Free World’, which all three bands took to the stage to perform together at the end of each performance. The NME journalist Terry Staunton had “a life-affirming moment” on the tour in Brașov, where he was moved to tears after experiencing what he described as “the greatest four minutes of my life.”

It’s almost a cliché in itself to say this, but grebo really seemed like a textbook example of build ‘em up and knock ‘em down…

Mary Byker goes so far as to suggest that the press were a significant contributing factor in the demise of Gaye Bykers On Acid: “We got written about, and I think what happens is if you don’t make it big time, it’s almost as if they feel like you’ve cheated them in a way, and they look a bit stupid after they’ve backed you so much. It’s quite swift, the retribution…”

It’s a bit ironic that one of the next big things after grebo had been written off was grunge…

“Grunge” or “grungy” is an epithet that was used on numerous occasions in the music press to describe the look and sound of bands like Crazyhead and Gaye Bykers On Acid – if James Brown hadn’t come up with grebo, it could easily have become known as ‘grunge’ instead. Although British grebo and American grunge can loosely be described as an amalgamation of punk and heavy rock elements, grebo drew on a much wider range of influences. Grunge was more homogenous, stylistically and musically, not to mention more listener-friendly, so it was arguably a safer bet as far as the marketing men were concerned, and easier for the music journos to compartmentalise. It also had the attraction of having some sort of ‘outsider’ cachet too. Although evolving around the same time, “uncool Leicester” could never compete with “cool Seattle”.

Even today, grebo is regarded as a bit of a joke, but does it deserve to be better remembered?

I think it does. Regardless of whether it was largely media-constructed or not, it was an important part of the 1980s musical landscape. But the negative connotations engendered by the media backlash at the time have been perpetuated ever since, and many so called grebo bands have been unfairly tarnished by association. I hope Grebo! will at least go some way in rehabilitating the reputations of Crazyhead and Gaye Bykers On Acid, if not the wider grebo genre. If you’ve never heard the Bykers or Crazyhead before, scratch beneath the surface of any pre-conceived perceptions and give them a listen!

Gaye Bykers On Acid are on tour in the UK 11-20 November 2021. Grebo! The Loud & Lousy Story Of Gaye Bykers On Acid And Crazyhead by Rich Deakin is available from Headpress