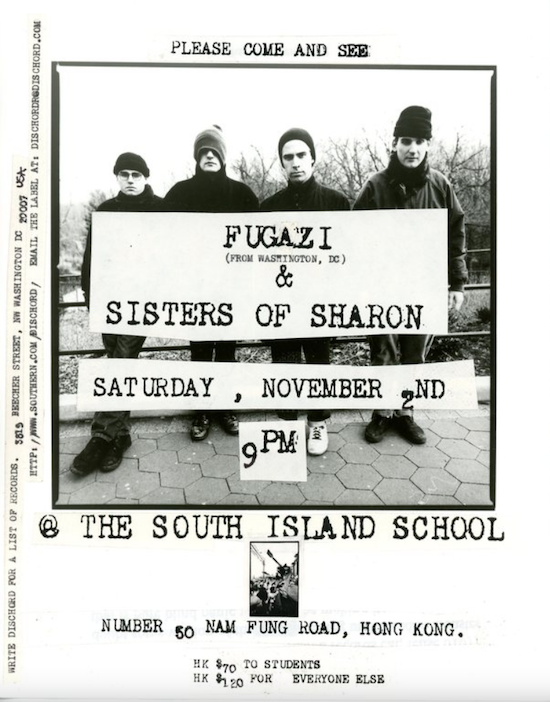

On my seventeenth birthday, 2 November 1996, underground American punk heroes Fugazi played a gig at my school in Hong Kong. By a quirk of fate, I was wearing a homemade Fugazi t-shirt the day the organisers of the gig were in the school hall looking at the sound system. They saw me and saw an opportunity. First, they let me in on the big secret (Fugazi were coming to town!), then they offered me the chance to sell tickets to the show in exchange for free entry and the chance to have dinner with the band. Of course, I leapt at it and so began my short career in door-to-door sales and grassroots marketing. I don’t remember whether I sold all the tickets I was given but I sold enough to move Ian MacKaye, guitarist and co-lead singer, to dedicate the song Birthday Pony to me from the stage (a dubious honour given the sentiment of the song, but still) and to grant me an interview.

The forty-five minute interview took place shortly after Fugazi had played a second, free show in Kowloon Park and just before we went for dinner at an Indian vegetarian restaurant. Ian was very accommodating and gave long, thoughtful answers to my questions. Listening back to it many years later I was struck by just how little the conversation was about music. I was almost entirely interested in asking him about Fugazi’s do-it-yourself ethos: the minutiae of how they operated as a band and how he operated his label, Dischord Records as a small business. I don’t think this was unusual. If you watch other interviews with Ian and Fugazi the interviewers almost always want to talk about their business practices and they are only too happy to oblige. On the rare occasion when they’re asked specific questions about their music they shy away from answering, mumbling about letting the music speak for itself. Their legacy is based less on what they did as it is on how they did it.

This is part of a broader narrative about the legendary American alternative music underground that’s celebrated in books like Our Band Could Be Your Life by Michael Azerrad, and documentaries like 1991: The Year That Punk Broke by Dave Markey, and extolled as an influence by the likes of Frank Turner, Biffy Clyro and Charli XCX. If you zoom out and look at this bigger picture, the same perspective applies: its lasting cultural impact was the means not the music. Punk remains relevant today because it built its own networks of operation instead of trying to hitch a ride on the mainstream music industry. The ethic of do-it-yourself inspired people around the world to set up their own performance venues, record labels, pressing plants, distribution companies, booking agents, management firms, and media channels.

Punk changed the world, becoming a part of the mainstream by making the mainstream adapt to include them. They weren’t the only ones.

After World War II very few people dared call themselves conservative in America. Conservative fringe groups were accused of being un-American. Liberalism, it was argued, was the true American tradition. Conservatism was considered a treacherous European import, a sort of fascism-lite. Fast-forward seventy years and ‘conservative’ is the most popular political identity in America. Republicans have been President for ten of the seventeen terms since the mid-twentieth century. Not only that: Democratic presidents have become consistently more conservative. At the policy level, Barack Obama’s administration was no more progressive than Richard Nixon’s.

Since the 1970s, the Supreme Court has leaned consistently conservative in its judgements. Americans also have a tendency to describe themselves as more conservative than their policy preferences suggest. Conservatism as a cultural identity keeps growing. So, how did America become so conservative – and what can progressives learn from this if they want to turn the tide?

If you want to change the present, you’ve got to have a good feel for the future. Historically, progressives have always been good at this – bargaining power for labour unions, the creation of the welfare state, as well as rights for women, ethnic minorities and the LGBTQ community were all won by farsighted leftivists.

The vanguard of the American conservative movement closely studied the grassroots method of change pioneered by the left. In the second half of the 20th Century, conservative activists hacked the method in the service of family values and individual self-reliance. This was precisely the moment – the late 1970s – when liberals became more short-termist, losing their grip on a coherent and compelling vision of the future. And what a moment it was.

In the 1970s violent crime rates doubled across America. By 1980, violent crime and property crime rates were four times as high as they’d been in 1960. In the 1990s, the effects of globalisation were increasingly being felt in America’s industrial heartland, and disillusionment with the labour unions’ inability to alter the direction of travel aided the rise of the cult of the entrepreneur. On the eve of the twenty-first century, the country seemed to many Americans a much less safe and secure place than it once was.

When conservative activists pictured honest Americans working hard to build a family home, they saw it like a Norman Rockwell painting – a fusing of cultural sentiments to pastoral landscapes that created a powerful vision of an American Arcadia. The backdrop was partly the South (which was religious and old-fashioned), partly the West (which was pioneering and freedom-focused), and partly the Midwest (which was down-to-earth and community-oriented). They called it Middle America.

And where else could these three regional cultures be combined into a single mythical geography of Middle America?

Suburbia.

Conservative organisers understood how suburbanites saw themselves – as proud homeowners, wary taxpayers, fearful schoolparents. Over the years, conservatives have refined their methods for gauging suburbanites’ fears and concerns and appealing to them. Today, this intoxicating vision remains as effective as ever – as Donald Trump proved so well in 2016.

The conservative movement was essential to America’s rightward turn, but they didn’t do it by themselves. They needed the money and reach of the conservative power elite. As fate would have it, the conservative elite was in the process of refining their very own method of culture change.

Back in the 1960s. Paul Weyrich had an idea. As a young press secretary in Washington DC during the height of the civil rights movement, he had watched a diverse coalition of church leaders, grassroots activists, campaigning journalists and policy wonks work with members of Congress to effect change. Behind the hard-fought victories of Loving v. Virginia (1967), the Voting Rights Act (1965) and the Fair Housing Act of 1968, Weyrich saw the work of a consensus-building network stretching all the way from civil society to the corridors of power.

Weyrich believed that conservatives should reverse engineer this liberal system. If the right were to once again attain hegemony over the American min, they would need their own consensus-building structures. Like the punks, they were going to need to create their own networks, their own institutions, their own infrastructure. There was just one problem. Conservatives had no organic base in civil society. So Weyrich bought one.

He tapped Joe Coors, heir to the enormous beer fortune, for a line of credit. In quick succession, Weyrich set-up the cornerstones of the conservative future, institutions like the Heritage Foundation, the American Legislative Exchange Council, the Committee for the Survival of a Free Congress, and the Council for National Policy.

These blandly-named organisations heaved into syncopated action. Heritage focused on the creation of conservative policy. Today, it’s one of the most influential think tanks in the world and the only one in the global top ten with an overtly ideological bent. ALEC helps Congressional representatives turn Heritage ideas into legislation. The Committee for the Survival of a Free Congress, now called American Opportunity, is dedicated to recruiting and training grassroots activists and politicians who can sell that legislation to the electorate. Perhaps the most important of all is the Council for National Policy, a networking forum that helps political doers, like Weyrich, connect with political donors, like Joe Coors.

Since then, many other conservative activists and tycoons have collaborated to build similar systems. For example, the Koch brothers, for so long the bête noire of the left, copied Weyrich’s model in the name of extreme free-market economics. Pragmatic conservatives with a feel for technology and entertainment, like Roger Ailes, Rush Limbaugh and Newt Gingrich, set up media outlets and the early infrastructure of what we now call a political echo chamber – two-way comms channels between the power elite and the grassroots. The conservative entertainment complex has become, of course, a key asset in the culture change assembly line first envisioned by Paul Weyrich half a century ago.

The first decade of my own professional life was shaped by constant change. I went through ten large-scale corporate restructures in as many years. I don’t think any of these restructures worked as intended – to make people more productive and the organisation more effective. We were trying to change the culture of the company by changing reporting lines, which is like trying to learn Spanish by going to French classes. Later, when I’d quit my job to become self-employed, I began to reflect on what we were doing wrong. I wondered whether there were lessons I could lift from the ways punk and the DIY ethos influenced me. The power of punk was a twofer: there was the promise of a destination (be the change you want to see in the world) but also the transformation inherent in the process (by being it you could change not just the world but yourself at the same time).

This was in 2016 and 2017, and at that time it was political populism, not punk, that was headline news. Like many people I was flabbergasted when Donald Trump was elected president. So I started reading about conservative American politics and began learning about a world I’d previously had little reason to understand. I felt a bit like an archaeologist, brushing away the sand to eventually uncover an enormous, longstanding edifice that had been hidden from view. The more I read about American conservatism the more I began to see it as a coherent and extremely effective culture change system. I discovered it had engineered its way into the cultural mainstream in much the same way as punk, by establishing institutions that worked together like an assembly line. They included academic research centres, policy-writing foundations, media companies, grassroots campaign groups, politician-training organisations, and coordinating committees that could herd these different cats into seamless alignment with one another.

In the forty-odd years since punk emerged it’s had to change its tune to stay relevant. Will it continue to evolve with the possibility that it will be reinvented again for a new generation as it was in the 1990s? Or will it simply be fossilised and used only as a stylistic anachronism that new fashions occasionally reference? By the same token, American conservatism now faces a reckoning of its own. Everything that the activists and elites held it to be ideologically was upended by Donald Trump’s 2016 election. They believed their constituents voted Republican because they demanded less government spending, ‘freer’ trade, ending welfare and deregulation. Trump won by campaigning on the opposite – trade isolationism, protecting Medicare and Medicaid, draining the swamp of elites who move with ease between government and industry and protect the 1% at the expense of the 99%.

The production line still works, but it’s making an increasingly irrelevant product. What happens next is anyone’s guess.

Red, White & Radical: What Organisations Can Learn About Change from the Rise of American Conservatism by Warrick Harniess is published by Routledge