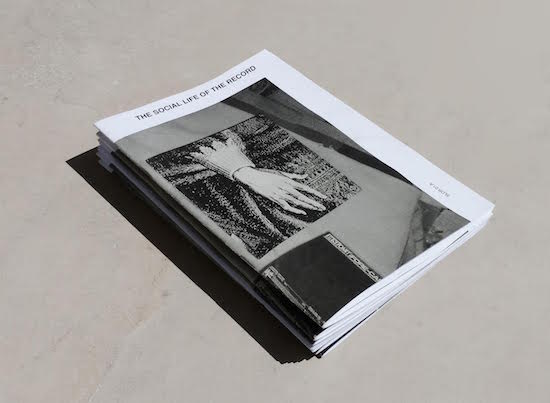

Last year, while walking around the booths at the Whitechapel Gallery art book fair in London, I found and bought a publication called The Social Life of The Record (The Social Life of the Record #1, Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere, 2013, Edited by Jon Bywater, Julien Laugier and Louise Menzies. Designed by Louise Menzies and Julien Laugier). As soon as I opened it, I immediately felt a connection; the little pamphlet mentioned an art show, which was not only music-related, but also serendipitously titled ‘Everybody Knows This is Nowhere’ — one of my favorite songs by Neil Young and, together with a few other pieces, the soundtrack of my two years as an Italian expat in Australia.

No matter how much Melbourne will always be the place to be for me (for the locals: I don’t mean this as a driving reference), and despite the cosmic nostalgia I still suffer nowadays when I think of it, there were times when I thought that place – Australia – was nowhere, that I wanted to go back home, and take it easy…

So I decided to get in touch with Jon Bywater, one of the authors that contributed to both the show and the pamphlet; I wanted to know more about a project that sounded familiar even though I haven’t heard of it before.

The exhibition was held at castillo/corrales in Paris (December 2012 – January 2013); it was a collaborative production on a “New Zealand character”, spun-off from the appreciation of New Zealand’s music from a foreign point of view. As the press release mentioned, the show touched on “the long-standing love affair in France for music produced in Aotearoa – New Zealand since the early ’80s".

Can we start by talking about the title of the exhibition and what it is concerned with specifically? ‘Everybody knows this is nowhere’ seems in fact to be a very evocative expression that describes not just a personal, but also a collective feeling of uneasiness — of being in a place which is desolate, far away from home and, to certain extends, unsettling. It’s that kind of phrase that sticks around in your head, easy to connect to on a sentimental level.

It has been quoted extensively (one example amongst many being the 2010 exhibition and book by the American photographer Ryan McGinley of the same title), which proves once again the expression’s universal value.

John Bywater: Neil Young’s ‘Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere’ was the A-side of the first single The Human Instinct recorded back home in New Zealand after a stint in London in the late ’60s. What attracts us to it as a title, to borrow in our turn, is that while it could seem that these Kiwis found their home country a kind of nowhere – they even chose to record a song by a Canadian – as underground rock aficionados know, they could also be said to make the song their own, and they re-titled it as an affirmation of a return: ‘I Think I’ll Go Back Home’.

Titles are fun. For me, the icing on the cake of a mixtape, for example, is a good title. Perhaps exhibition-making is like making a mixtape?

The show developed from various collaborations; how did they start?

JB: The exhibition grew out of the initial proposal that castillo/corrales make a presentation of a book, that I was a contributor to, Erewhon Calling – a good book about underground music in Aotearoa / New Zealand.

Louise Menzies makes artist books, works in other relationships to print, and was a fan-at-a-distance of castillo/corrales and Section 7, Paris’s best art bookshop. So when she and I were staying in the city for a month in the summer of 2012, we went to visit. On their side, music from NZ was an old interest, and so the book came up in conversation. From there the possibility of extending the book presentation into the exhibition developed.

It was important to all the elements of the project that a variety of standpoints on what ‘New Zealand’ is might show up, and so the exhibition included artists (and writers) with varying claims to an NZ identity, including a self-proclaimed ‘ex-New Zealander’ and people who were simply not New Zealanders, as well as expatriates and affiliates of various kinds. The exhibition itself wouldn’t have happened without the exchange between Louise and I and castillo/corrales (we worked most closely with Thomas Boutoux, Benjamin Thorel and Julien Laugier), and so it was in a way about staging an encounter more than a completely shared outlook.

An exhibition such as ‘Everybody Knows This is Nowhere’ shows perfectly art (and music) as relational objects; their particular products/artifacts – artworks, records, etc. – embody a relation, a connection, which can be sentimental, logical or cultural at large, between the people that participate in the artistic event. How do you think music, as an object-driven matter, (i.e. the obsession with the collection of paraphernalia, or even a sort of record-fetishism), is a relation-making tool for people who communicate and bond even though far away?

JB: I am a record collector myself. My own relationship to music, as well as to many far-flung places and phenomena, has been shaped by the global circulation of LPs, 45s, tapes and CDs, and music magazines – as well as and in concert with the Internet, of course. I am a witness to this ‘fetishism’, if you like, to what is undoubtedly a partly generational practice of using –remembering, sorting, valuing – music through physical media, rather than through data that might be physically stored however, wherever.

Of course, music forms relations between musician and listener, between one listener and another, and so on, whether it is live or recorded, a seven inch or an mp3. But the formats that move through the postal system rather than through the internet can intensify some of this in certain ways; to start with perhaps because they can be better mnemonics for the things they express, as well as the way they can accrue the special value of the scarce.

In one way, the ‘far away’ was what the exhibition was about: how artifacts can accrue value for the way they are exotic, and perhaps also how that in this they might refresh for us the value of what is under our noses.

You often write about the significance of place. I totally agree with the idea that geography matters; growing up in a small town in Italy I always felt a distance – both annoying and challenging in some respects – between me and the music world I was looking at (punk, post-punk, new wave). On the one hand, this was frustrating because of the language, which acted, and still does, as a barrier (all the music I loved was written in English), and the geographical misplacement, always being ‘elsewhere’, where very little happened. On the other, I guess, this situation was challenging in terms of imagination and desire; I learnt how to desire (desire to be somewhere else, for example), which is a drive that later on in life has brought me to travel extensively.

How was this topic, the significance of the place, expressed in the visual outcome of the exhibition?

JB: You are describing precisely the dynamics that the project might have hoped to figure forth! To begin to transpose your description of these orientations and desires to the New Zealand case, we need only substitute accent for language…

In the exhibition, the question for the audience was exactly as you put it: does where this work comes from, or the identification with New Zealand show up? Is it visible? Does it matter? In simple terms, one or two works thematised place, others represented it, directly or in passing, while others just happened to be by a ‘New Zealander’. Who saw what in the visual outcome, I imagine, varied. And that, fundamentally, was what seemed interesting, and a relativity that we hoped to foreground.

Identity has always been a pivotal theme in art; artists constantly feel the need to question themselves and their beliefs as a product of their location and culture. Is there a particular New Zealand band that, in your opinion, has focused on this exact topic with their lyric and music?

JB: Certainly from early rock’n’roll to more recent hip hop, the question of whether it is more or less correct to not slip out of your New Zealand accent has come up; but no, I can’t think of an interesting, sustained musical response to the question. As Louise reminds me, Tori Kudo of the long-running group Maher Shalal Hash Baz was interviewed recently by Bomb, and he talked about the way a Japanese musical identity is subject to a feedback loop.

I’ve long been curious about the way that some of the most ‘New Zealand’ music has been seduced and in some cases sent off the rails by an awareness of its international reception. If this suggests that the best musical expression of ‘New Zealandness’ might be the most self-consciously defiant continuation of an emulation of something from somewhere else that came out strangely, here, the answer is easy: the Dead C.

Jon Bywater is a Senior Lecturer at Elam School of Fine Arts, the University of Auckland, Aotearoa New Zealand, and writes on art and music. His work has appeared in periodicals such as Afterall, Artforum, Frieze, Mute, Landfall, The Listener, Art New Zealand and Reading Room, and in numerous monographs and exhibition catalogues