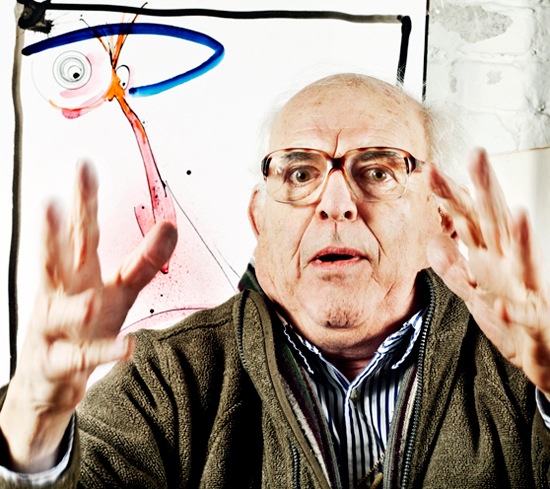

Photographs taken for The Quietus, by Phil Sharp

(This interview is part one of a two part feature, you can read the second instalment here.)

‘Dealing with Ralph made the whole rotten trip worthwhile for me, in some odd sense. I liked the bastard immensely, and his awkward sensitivity made me see, once again, some of the rot in this country that I’ve been living with for so long that I could only see it, now, thorough somebody else’s fresh eye.’ –Hunter S. Thompson, letter to Scanlan’s magazine, 27 May 1970

‘Before I left New York a month later, I asked Warren Hinckle III out of curiosity about my Kentucky drawings. I rarely part with my work and I certainly would not have willingly parted with those ones… I never did find out, but, wherever they are, they still belong to me…’ –Ralph Steadman, The Joke’s Over: Memories of Hunter S. Thompson

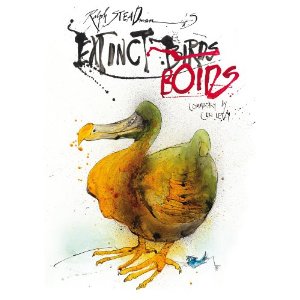

YOU KNOW IT when you see it, the Steadman style, exploding inks like the splashing aftermath of a man thrown overboard, darts and lime lines like needles, concentric circles, reds like merlot thrown over snow. While Steadman’s illustrations are immediately associated with figures like George Orwell, Kurt Vonnegut or Hunter S Thompson, focussing on his literary associations and ‘bitter cartoons’ of politicians overlooks a breadth which includes books on wine and wildlife, his interpretation of Alice in Wonderland, or his child’s eye view of adulthood, That’s My Dad. Into this comes Extinct Boids: his serendipitous collaboration with conservationist and film-maker Ceri Levy, capturing one hundred species of bird, some extinct, others last spotted only in the farthest reaches of the duo’s imagination.

Beginning after Levy chanced upon a mural by Steadman at the 2010 Port Eliot Literary Festival, the book is a result of an email asking for a single contribution to Levy’s exhibition The Ghosts of Gone Birds. Their correspondence and friendship developed, however, and the birds kept arriving, Levy’s commentary capturing the construction of the book as it happened. Extinct Boids has a suitably Gonzo air, reasserting Steadman’s equal claim as originator, defining and continuing a visual style which began in the counter-cultural foment of America in the 1960s and 1970s. Steadman first met Hunter Thompson for ‘The Kentucky Derby is Decadent and Depraved’, a story appearing in the short-lived Scanlan’s magazine, his splashes and dashes capturing Thompson’s high-octane misanthropy and dramatic vandal’s worldview. The attitude resonates to this day in Steadman’s earthy timbre, the diction of a weathered thespian enlivening his talk, his jokes and reminiscences of Thompson, who eventually ended his life with a self-inflicted gunshot to the head in February 2005.

With Extinct Boids, Steadman, now aged 76, and Levy have become the inheritors of a stance and attitude that echoes, more than thirty years after its invention, a sense of fun and defiance which makes even their press part interview and part eavesdrop on a wayward and provocative conversation that laughs not only in the face of authority, but extinction as well. Coming from a career built in the overlapping edges of illustration, art, journalism and literature, their partnership stands on the same certainty of vision that allowed Thompson’s writing to flourish. In the popular press, more so than text or even photography, illustration defies editorial intervention, which means that with Ralph Steadman what you see is exactly what was meant. This explains his first assertion about journalism: ‘What you should do is make it quite clear to any editor you work for: you do not have your articles edited. Hunter never did.’

Never?

Ralph Steadman: If he put it in, it was meant to be there.

But that didn’t stop things from being cut out from time to time. The Kentucky Derby story lost about 4,000 words between production and eventual publication.

RS: It might have done, but that would have been by skulduggery and underhand methods. They were afraid of what he would say, and he’d scream and shout.

In your memoir The Joke’s Over, you tell of sending the original Kentucky artwork off and never seeing it again. Is that still the case?

RS: That’s right, the ones that I did for the Kentucky Derby. It was a ‘derby’, though, they call it that there – I have to keep saying it, the derrrby. It’s a derrrby. I did drawings for it. And I got one of them back by the way! I’ve got an original. It’s got the owner leading the horse, a little dwarf-like jockey on the saddle, and the horse has got a big dong on it, and so has the owner. He’s got a big dong. It’s hanging out of his trousers.

Was it difficult to track down?

RS: No, somebody sent it to me! Thought, ‘I’ve had this long enough, it’s time I sent it back to you!’ Unbidden. I didn’t ask – it came. So I gave him two or three prints, things like that, thanking him very much for being so kind.

That’s a very good deed.

RS: That’s the only thing that anyone has ever done of that kind. Usually they’ve been stolen, which is what Jann Wenner did. He stole all my originals that I did for him, and they’re on the wall of the offices of Rolling Stone in New York.

Were they the original pictures for Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas?

RS: All the Fear and Loathing pictures. They’re all with Jann.

Why did you send the originals instead of copies?

RS: Well because at the time that’s what y’did. In 1970 we still hadn’t got email and stuff like that, y’know. I could have sent photocopies, I suppose… But I had them done and I thought, ‘Well, I don’t want to spend any money before I’ve made anything,’ if y’know what I mean. That’s how I felt then. But it was a mistake.

Have you raised the matter subsequently, with Wenner?

RS: No, because Jann Wenner is a crook, and a cheat, and a liar. I didn’t like them being there, but it’s OK then pal, I hope it chokes you one day. There we go –

Ceri Levy: Just to let you know I’m still here!

RS: I know! Haha! Occasionally, Kiran, you go away from the phone. I mean, you go, what I mean is, your voice breaks down. I think, oh dear, what’s happening? I think you move backwards from the phone.

Oh I see – it could be the proximity of the microphone, or the wireless signal connecting the computer to the internet…

RS: Oh that might be it; it’s probably something to do with the satellites that are going round the Earth, hitting each other… there are tonnes – there’s too much of it around. I mean there’s electronic pollution now, and that’s what we have to work with.

It’s a big concern for parents with newly-born babies.

RS: I’ll bet. Do they have radioactivity in them, stuff like that?

I think so, or something more akin to microwaves.

RS: Well that’s even worse – suddenly you’ve got a cooked child! Or an under-done child, even worse!

CL: It’s very hard to work out because they grow all the time. They’re not the same from month to month.

RS: They’re much more tender when they’re little. A few months old. Or a few days old. Then they’re perfect. Put ’em in the microwave, they’ll be just right!

CL: I’ve given up microwaving – and not just children. But I’m not sure this is where this needs to go… it’s kind of where we’ve ended up.

No more dong-talk. Before today Ceri and I had a great talk about the new book, Extinct Boids.

RS: Oh yeah. You know I hate birds, don’t you? I’ve had to look at some this morning! Bloody things, pecking away everywhere… peck, peck peck! I can’t stand them. No, they’re horrible things. I saw a bird this morning, and I thought for a minute, oh, it’s a crow, but no – it’s got orange under the wings. I don’t know what it is because I didn’t do many birds with their wings up. Ceri might know. Ceri knows more about birds than I do. He knows two years more than me, about birds, I think.

CL: What’s the question?

RS: The question! What was the bird, what did I see this morning?

CL: What did it look like? What colour was it?

RS: I told you – it was a lovely orangey-brown, under the wing.

CL: A jay.

RS: I thought it might be. It could have been a jay, yes. It’s quite possible: it was about the size of a crow, but it wasn’t a crow, no. Definitely. In the garden. So, now we’re arguing on the phone. We’re not even talking to you. I don’t know what we’re doing.

CL: Jays are beautiful creatures – I love them. They’re quite mysterious as well, and then when people see them they often phone in to bird people saying, ‘I’ve seen this most amazing bird, it must have travelled from thousands of miles away.’ They look like very exotic birds, because they’ve got that flash of light blue across the wing and things. An electric blue, really. They’re like no other bird we have in this country, a peachy sort of brown body.

RS: It’s a bit like seeing a dodo fly past, really.

CL: Exactly – it’s unexpected.

RS: Well that’s what we’ve got to see now: we’ve got to reintroduce the dodo, somehow. I don’t know – cross a chicken with lame dog or something.

CL: That’s possibly not the right combination, but we’ll have a look at it and see what we can get in the melting pot.

RS: Oh yes, you’re coming down. Are you coming, Kiran? From America. Are you in America?!

West London—

CL: Come down tomorrow. Your photographer’s coming down.

RS: You could come down; I’ll give you something to eat and a bit to drink. Or you can have a cuppa tea, whatever. That’s what you could do, you know. What you’re doing now is what you’d be doing. Today you’ll say afterwards, oh shit – I didn’t ask him about so-and-so. You know?

A follow-up interview.

RS: Because you forgot something.

CL: Everything, he forgot. ‘All he did was talk about jays in the garden, and how to cook a baby.’ Or children. You gotta be careful. People draw the line at putting babies in microwaves. Small children, that’s acceptable.

RS: I think preferably, Irish babies.

Ah… they tend to be plumper, bred on carbohydrates. More meat on the bone.

RS: Oh of course! That’s true, yes. But how did we get on to this cannibalism?

CL: I think you did it.

RS: Look, I’m a corrupting influence, I really am… I shouldn’t be like this. But I don’t know what else there is to talk about.

Given revelations about the world of late – widespread paedophilia, horse meat in burgers – it’s as if the people who are generally considered weird are amongst the purest and most innocent people around. I don’t feel that you’re a corrupting influence.

CL: He’s corrupted me!

RS: Ceri used to be a nice fella. Now he’s filthy!

Ceri since you’ve come to know Ralph, how far has your life gone off the tracks?

CL: I’m a mess. I’m invariably unshaven, unkempt, I find myself looking at strange “cartoons”… It’s terrible, the way my life has become now—

RS: He doesn’t wear a belt. I distrust people who don’t wear belts. Or braces.

CL: No braces, no sock-garters—

RS: He doesn’t do any of that.

CL: None of it! And this is all because of Ralph. I used to be nine-to-five and work in the City and now look at me. It’s all gone pear-shaped. Things have definitely changed: my days are a different shape in a lot of ways since I’ve known Ralph, because I speak to Ralph pretty much every day, and we discuss things and go through ideas…

RS: I ring you up and say, ‘shut up!’ and he’ll say ‘shut up!’ back, y’see. What did you say shut up for? You said it first! No I didn’t! You’d get an argument going, that way. That’s a good way to do it.

CL: And the best is to argue when no-one’s got a clue what you’re arguing about. Needless and pointless.

RS: Needless smut. There’s a Needless Smut in the book. And the Needless Smut is our favourite bird.

CL: Yep. He is. He means everything to us.

RS: Ceri just warned me: ‘I don’t want you to talk about any needless smut.’ And I thought, “Hoo! That’s a good name for a bird!”

That’s all to be found in Extinct Boids, that background, as well.

RS: Yes. It’s one that I like. I like the indignant look on the face of the Needless Smut: How dare you. It’s a marvellous way to think about things. It’s like the joke I heard. I think it was Barry Cryer that told it. Very funny. I’ll tell it, if you’ve got a moment. It’s about a man who’s got a parrot:

The parrot starts acting up. Who’s a pretty boy then? ‘Well you’re not’. Starts being rude to his owner who says, look, if you go on like that, I’ll put you in the fridge for five minutes. But the bird is rude again, so the man says right! That’s enough! I’m putting you in the fridge. So he puts him in the fridge for five minutes then brings him out and says: ‘Well, are you going to be better? ‘No, you shit-face! I think you’re uglier than ever! Bugger you!’

So the man says right, you’re going in the fridge for ten minutes. So he puts him in the fridge for ten minutes, then brings him out again and says, Right! Are you any better now? ‘No you old fart! I’m not going to bloody well bow to your wishes! I don’t give a damn! I shall make a rude mess on the floor if I need to! I’ll do it now!’ Right, wow, and he does it.

Right! You’re going in the fridge for fifteen minutes! He brings him out again and says, right, you better now? ‘Well,’ he says, ‘I don’t feel any different, but I’m a bit worried. You’ve got a chicken in that fridge. What’s he done wrong?’

CL: Ah… didn’t he say… ‘He must have done something really bad?’

RL: Yeah right – something like that! Sorry I haven’t… I got the punchline wrong. Haha – a de-feathered chicken, and it’s been roasted. OK… never mind. We have a thing going, for fridges and microwaves.

CL: Kitchen destruction of creatures and children. Sorry Kiran, you probably have a very serious point to make now.

RS: He won’t be forgetting this now: and we’ve got some stories we could tell about you, pal.

Which stories do you have about me?

RS: About you? OK: You’ve just lost your job. And have been sending sexually explicit messages to a fifteen-year-old girl! How’s that? It was in the Kent Messenger…

CL: He sends me the Kent Messenger emails. And the story probably is there, now that you’ve asked him to do that. The world’s going to be very different once you’ve finished this call. That’s what happens. Don’t ask Ralph to tell you a story, because it’s like asking him to draw something. It comes to life, like he did with these Extinct Boids.

RS: It’s a frightening and fraught business. I’ve just done a thing on Orwell, by the way.

I wanted to ask, as you’ve previously illustrated Orwell’s books.

RS: I’ve illustrated Animal Farm, and I’ve done drawings for Orwell in different forms and ways. I’ve done several drawings of Orwell, and they’ve used one, full-page, in the review section of the Guardian. It’s George Orwell, with a pig wearing his hat. It says on it: ‘George’.

How do you feel about Orwell? He’s sometimes considered a bit of a saint. Is he untouchable?

RS: He’s not untouchable, but in fact, I was thinking that if he was down and out around the high streets of any town in England today, he’d do pretty well behind the superstores. There’d be food bins, and he could live quite well, on the stuff they chuck out. I’ve written here:

For protection, he wears dark dungarees and a cloth cap, and holes up in a spike, which is a doss-house, as it is more familiarly known, he lives in a room along with variously six to twenty other tramps, some still in bed all day. He tramps around Waterloo Road, Tower Hill, Pennyfields, and spends more time in South London. He writes of the current pension rate being ten bob a week, which I thought, sounded pretty good.

Of course George shunned the religious fringe of Mormons, Jehovah’s Witnesses, any of them – ‘show me god, and then I’ll believe’, he said. Hoped for butter but got margarine. He was prepared to kneel but not say prayers. But it got him a bun and a cup of tea. Maybe he could have written a tramp’s charter, or perhaps Down and Out is exactly that. It occurred to me that poor, as some may be, they do not actually respond favourably to, or accept the condition for themselves, but only as being temporarily down on their luck, having known better times. Down and Out, however, is even today, a graphic tour-de-force.

He adds a caveat, at the end of the book, that ultimately he has only seen the fringe of poverty, but has never truly suffered a tuppenny hangover at the end of rope. I believe that if Orwell were around today he would say ‘Holy god! Things are worse now than they ever were!’

I would say that, wouldn’t I, having swept the floors of Woolworths, and then oiled them, on a Friday night. My hated old grammar school headmaster saw me and treated me with the contempt I probably deserved.

OK? That’s what I wrote about George Orwell. Today’s Guardian, if you can get a copy.

You wrote and illustrated the piece?

RS: A guy called Stuart Jeffries wrote the article but he included some of this that I wrote. I wrote a letter directly to him, saying, if you like, ‘put my comments in if they’re relevant.’ That’s what I sent. They used part of it.

That’s exactly the kind of thing that compels people to buy a printed paper these days.

RS: I bought two copies of it! It’s nice to be offered work to do, you know?

I recall once writing an article on the Orwell Prize for political journalism named ‘Orwell with an iPad’. But the exciting part was the illustration by an American named Rebecca Hendin who showed Orwell gazing at a flower held gently between his hands, while around him distracted young people looked at images of flowers on iPads.

RL: If it’s true, if it was more powerful than whatever the article was about: as Ludwig Wittgenstein said, ‘the only thing of value is the thing you cannot say.’ It means that you can draw things in pictures that you just can’t put into words. That is what I think might have impressed you about it. Sorry, I was going off the point there. That’s the problem with me, I go off the point! What were we talking about? Was it birds? Oh! Fridges, and…

CL: Ralph, do you think Kiran might be the perfect man to try and work out Grossenheimer’s Laws of Adiabatic Masses?

RL: Oh you shouldn’t mention that! That’s absolutely – that’s the whole subject of my – that’s my next premise.

CL: Let’s not mention it again. Let’s never mention Grossenheimer’s Laws of Adiabatic Masses, ever again.

RS: I don’t know where I got it from. Years ago. But I knew immediately. I would say it: ‘Grossenheimer’s Laws of Adiabatic Masses’. And god knows what they are, but I’d love to find out. I looked it up, and I found ‘adiabatic’. I think it somehow came together as a combination of words.

Is this something that cropped up during the work for Extinct Boids?

CL: I think Ralph’s been working on this for a long time.

RS: Nothing to do with birds – I think it was already there.

CL: Because, as everyone knows, Grossenheimer’s laws have been laws for a long time.

RS: Have they? Yes, well… maybe and maybe not. I don’t know. The jury’s still out, on that one. In the case of Grossenheimer versus the state – it’s still out.

Before Grossenheimer you mentioned Orwell, but whenever people think of your work, Ralph, the immediate association is with Hunter Thompson.

RS: It is, yeah.

However throughout your working life you’ve illustrated a number of great writers. I was curious about Kurt Vonnegut.

RS: He was the most wonderful man and such a lovely friend, he was. God, I thought he was a nice man.

Your book with Will Self – rather the second one, Psycho Too – is dedicated to Vonnegut, opening with a tribute sketched on the tablecloth of a New York restaurant.

RS: That’s right, yes. And also he sent me something that said ‘life is no way to treat an animal.’ He had lovely thoughts, like that. I’ve got a thing from him. It’s right here, on a black sheet of paper. It’s called ‘Trout’s Tomb – Kurt Vonnegut, 2004.’ Hand-printed by Joe Petro III. He’s our friend in Kentucky.

‘For Ralph, TP’. I don’t know what TP stands for. One over two, so there were two of them. He sent one to me and he must have sent one to Joe. And it’s written in gold, on a tombstone: ‘Life is no way to treat an animal.’ Lovely, isn’t it? It’s such a lovely phrase.

Vonnegut’s Breakfast of Champions was turned into a film starring Bruce Willis, but the book contains illustrations by Vonnegut himself.

RS: He loved drawing. That’s what he really wanted to do – he didn’t want to write. But he did, because you know, he went to Dresden: you know, Slaughterhouse-Five, which is a very harrowing book – but so wonderful. He didn’t write it for twenty-six years after it happened! And he was one of the people, holed up in the kind of fridge that they hid themselves in. It was in the slaughterhouse, that’s it, in a fridge. A slaughterhouse fridge, it saved them, from the bombs of Dresden.

Amazing story, really, and he didn’t tell it until twenty-six years after it happened, the war.

Another book with doodles and illustrations was published on the first anniversary of his death – Armageddon in Retrospect.

RS: I’m not familiar with it, but I can understand why he’d said that. It was like that, I’m sure. The end of everything was happening. But he survived. When he did really start writing, he spent the rest of his life pretty well writing to thank people – to give something back. I think the raison d’être of his life was to repay. This act of gratitude. How about that?

He held an incredibly sympathetic view but a subtle and tempered despair at the violence that we visit on each other.

RS: And a completely different man to Hunter Thompson, by the way. Totally different. Hunter said to me, ‘Don’t write, Ralph. You’ll bring shame on your family.’

That’s included in The Joke’s Over.

CL: You can’t fool him, he knows it all you know!

RS: I know, all right, I’m trying to just catch him out, but I’m not! Never mind – he could catch me out at any moment!

There’s a point of connection with Extinct Boids: Didn’t Thompson keep a green bird named Edward?

RS: Edward. He kept it in a cage, and occasionally it would sit outside the cage, on top of it, and be quiet as a mouse, really. And then suddenly say something. Whatcha doing? Hunter had a way of talking, like, Nevermind Ralph. And then the bird would be able to say it. A mynah bird. He talked, and it was his pal, y’know?

He grabbed the bird, one day, and said: ‘Now Edward, you’re going to die, Edward… you’re going to die and there is no bird god that’s going to help you now, Edward. You’re going to die…’ and the bird is sqwaaah! Squawking at him, and he’s holding on to it, you know. It was extraordinary. Bird torture! In Aspen, Colorado, he had that.

What this just entertainment, or was it something else?

RS: It was entertainment, really, and he was having fun. He loved to make fun of people, in a way. I mean me; I was like Edward.

Do you feel he ever mistreated you?

RS: Yes, in a way, I think he did. I’m rather kind-hearted. That’s the problem with me. I just drew filthy cartoons. He always used to call my work ‘filthy scribblings’!

In his letters there’s something that seems touching, or at least direct and honest, around the time of ‘Kentucky Derby’, in a letter to Don Goddard at Scanlan’s magazine. He said: ‘Dealing with Ralph made the whole rotten trip worthwhile for me, in some odd sense. I liked the bastard immensely, and his awkward sensitivity made me see, once again, some of the rot in this country that I’ve been living with for so long that I could only see it, now, thorough somebody else’s fresh eye.’ That suggests a great deal of affection, but…

RS: He has, but he hates to show it. He believes, it shows weakness. And that’s how he used to treat you, y’know, ‘you old bastard.’ And ‘the bastard was good to me,’ or something. He always had the addenda of… It was an insult couched in kindness. Covered in it, if you like, to soften the blow.

Was it a macho thing, a sportsman’s thing almost?

RS: It could be, and he liked sport. He liked to watch it – he didn’t like to play it much. He has been known to play. I think he played softball, and he played a bit of American football, and he always had a ball around the place, and was always throwing them. We always had to play with air rifles and different things. He had guns – he had twenty-three guns! All fully loaded, at most times. And he told me, he said: ‘I’d feel real trapped, Ralph, in this life, if I didn’t know I could commit suicide at any moment.’ Which was true. And he did.

You helped him plan his funeral.

RS: That’s right. He was going to do it, when he was ready. We even went to the funeral director in Basalt, I think it was, or let me see… maybe Basalt, and he wanted to talk about it. No – we were somewhere else. One of the early trips together. I’m trying to think where the hell it was.

We wanted to talk about Hunter’s death. So it was, ‘well, are you sick?’ – ‘No, I just feel that one day I might commit suicide suddenly, but I need Ralph to know what exactly I need, on my tombstone, or whatever else.’ Which we honoured, of course – to the letter. Johnny Depp paid for it. We went to Aspen, Colorado, to have this big fist – it’s a two-thumbed fist, if you can imagine.

‘Don’t forget Ralph, two thumbs.’

RS: ‘Two thumbs,’ that’s what he said. And he wanted it on a tall monument, and the big fist, on top. And then his ashes would be in some kind of rocket, on top, and when the moment came it would burst open, and his ashes would be thrown up into the air, to communicate with heaven, if you like. I think he was secretly religious.

Why is that?

RS: Well only because I think that he was hoping that if there was a life after death, he would be accepted up into heaven, he could do his own Gonzo, up there, y’know. The first two letters of ‘God’ are the first two letters of ‘Gonzo’!

The Joke’s Over opens with a brief reminiscence of the ceremony and the 150ft tower. You also mention that Thompson took the easy way out with suicide.

RS: He did, yeah. I think he did. It’s the coward’s way out, to do that.

Do you still feel that way?

RS: In a way, yeah. I mean I’m finding it tough, you know, as I get older, thinking ‘oh my god…’ But all I want to do, when I go, is to go to sleep one night, and not wake up the next morning, and not know about it. That’s the only way I can think about making it worthwhile. Decent. I don’t want to go through – people shouldn’t have to go through – rest homes, and all that shit. I’m not going to do that.

The general public image of Gonzo and the art and the writing has you and Thompson pinned to the page at certain stage in your lives, as young energetic men, cavalier—

RS: We were. We were young then. A lot of people keep telling me, ‘Oh, no, Ralph, he loved you dearly, he thought the world of you…’ But he never treated me like that. He treated me terribly, in a way that I realised, ‘Oh god, it’s just him being him.’

A feature published in the Independent mentioned that Thompson had on occasion caused tears in the people around him.

RS: Tears of laughter, often.

But also tears of sadness.

RS: He used to grab his son Juan by the ear, and twist him round in a circle. He somehow couldn’t quite separate the love from… the peculiar nature of his tormenting. He wasn’t the best parent in the world, but he was an interesting parent. And he had a wife which he… well, she decided to leave him, go on somewhere else – Sandy Thompson – she went and married someone else. She went off for a year, round the world with some bloke.

He [Thompson] suddenly started making all kinds of liaisons with any woman who was around the neighbourhood. ‘Ooh! Meet Hunter Thompson? Yes, please!’ And they ended up in bed with him. The lucky bugger! That’s nice. Well, it’s either that or – what are you going to do, celebrate celibacy?

Reading William McKeen’s biography, I didn’t realise that Sandy had a stillborn daughter, Sarah. The doctors said they’d ‘dispose of’ the body but Thompson broke in to the morgue and gave a home burial.

RS: Yeah, that happened, but it didn’t stop Hunter’s way, or his philandering, which went on quite a lot, I think. He quite liked women, and that was it. Not a bad thing to like, really.

I was struck by the difference between the public image of the artist and the ongoing reality of aging.

RS: Listen, ah, wait a minute, wait a minute – Ceri’s only forty-three.

CL: Well that’s in inches!

RS: Haha! Ooh, good one! Good one!

CL: Thank you. Thank you. I’ve just been biding my time.

Extinct Boids by Ceri Levy and Ralph Steadman is out now, published by Bloomsbury. The Hunter S. Thompson back catalogue is published by HarperPerennial

Follow @theQuietusBooks on Twitter for more