It is well known that the Banshees were formed as a result of the future Siouxsie and Severin meeting at a Roxy show in 1974. Unlike the Birthday Party, who were famously disgusted when they arrived in London to find it dominated by new-romantic poseur-pop, the Banshees belonged to an art-pop lineage which had a relationship to music that was neither ironically distant nor direct. For all their inventiveness, for all the damage they wreaked upon rock form, the Birthday Party remained romantics, desperate to restore an expressive and expressionistic force to rock; a quest which led them back to the satanic heartland of the blues. By contrast with this carnal heat, the early Banshees affected a deliberate – and deliberated – coldness and artificiality.

Siouxsie came from the art-rock capital of England – that zone of south London in which both David Bowie (Beckenham) and Japan (Catford, Beckenham) grew up. Although Siouxsie was involved with punk from the very beginning, and although all of the major punk figures (even Sid Vicious) were inspired by Roxy, the Banshees were one of the first punk groups to openly acknowledge a debt to glam. Glam has a special affinity with the English suburbs; its ostentatious anti-conventionality was negatively inspired by the eccentric conformism of manicured lawns and quietly tended psychosis Siouxsie sang of on ‘Suburban Relapse.’ But glam had been the preserve of male desire: what would its drag look like when worn by a woman? This was a particularly fascinating inversion when we consider that Siouxsie’s most significant resource was not the serial-identity sexual ambivalence of Bowie but the staging of male desire in Roxy Music. She may have hung out with ‘Bowie boys’, but Siouxsie seemed to borrow much more from the lustrous PVC blackness of For Your Pleasure than from anything in the Thin White Duke’s wardrobe.

For Your Pleasure songs like ‘Beauty Queen’ and ‘Editions of You’ were self-diagnoses of a male malady, a specular desire that fixates on female objects that it knows can never satisfy it. Although she ”makes his starry eyes shiver”, Ferry knows “it never would work out”. This is the logic of Lacanian desire, which Alenka Zupancic explains as follows: “The… interval or gap introduced by desire is always the imaginary other, Lacan’s petit objet a, whereas the Real (Other) of desire remains unattainable. The Real of desire is jouissance – that ‘inhuman partner’ (as Lacan calls it) that desire aims at beyond its object, and that must remain inaccessible.”

Roxy’s ‘In Every Dream Home a Heartache’ is about an attempt, simultaneously disenchanted-cynical and desire-delirious, to resolve this deadlock. It is as if Ferry has recognised, with Lacan, that phallic desire is fundamentally masturbatory. Since, that is to say, a fantasmatic screen prevents any sexual relation so that his desire is always for an “inhuman partner”, Ferry might as well have a partner that is literally inhuman: a blow-up doll. This scenario has many precursors: most famously perhaps Hoffman’s short story ‘The Sandman’ (one of the main preoccupations of Freud’s essay on ‘The Uncanny’), but also Villiers de L’Isle-Adam’s lesser known but actually more chilling masterpiece of Decadent SF, The Future Eve, and its descendant, Ira Levin’s Stepford Wives.

If the traditional problem for the male in pop culture has been dealing with a desire for the unattainable, then the complementary difficulty for the female has been to come to terms with not being what the male wants. The Object knows that what she has does not correspond with what the subject lacks.

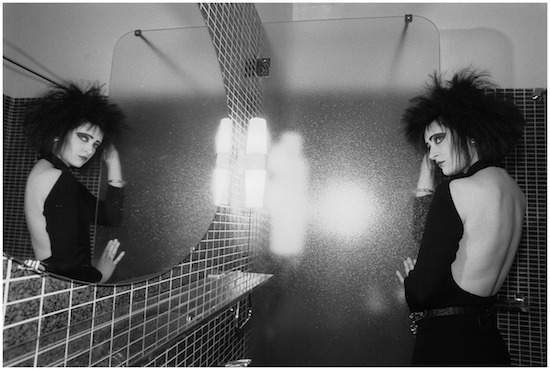

Remember that the original sense of glamour – bewitchment – alludes to the power of the auto-objectified over the subject. “If God is masculine, idols are always feminine,” Baudrillard writes in Seduction (1995), and Siouxsie differed from previous pop icons in that she was neither a male artist ‘feminised’ into iconhood by fan adoration, nor a female marionette manipulated by male Svengalis, nor a female heroically struggling to assert a marginalised subjectivity. On the contrary, Siouxsie’s perversity was to make an art of her own objectification. As Simon Reynolds and Joy Press put it in The Sex Revolts, Siouxsie’s “aspiration [was] towards a glacial exteriority of the objet d’art” evinced through “a shunning of the moist, pulsing fecundity of organic life”. This denial of interiority – unlike Lydia Lunch, Siouxsie is not interested in “spilling her guts”, in a confessional wallowing in the goo and viscera of a damaged interiority – corresponds to a staged refusal to be “a warm, compassionate, understanding fellow-creature” (Žižek). Like Grace Jones, another singer who made an art of her own objectification, Siouxsie didn’t demand R.E.S.P.E.C.T. from her bachelor suitors (with the implied promise of a healthy relationship based on mutual regard) but subordination, supplication.

In Rip It Up and Start Again, Simon Reynolds says that the early Banshees were “sexy in the way that Ballard’s Crash was sexy,” and Ballard’s abstract fiction-theory is as palpable and vast a presence in the Banshees as it is in other post-punk bands. (It’s telling that the turn from the angular dryness of the Banshees’ early sound to the humid lushness of their later phase should have been legitimated by Severin’s reading of The Unlimited Dream Company.) But what the Banshees drew (out) from Ballard was the equivalence of the semiotic, the psychotic, the erotic and the savage. With psychoanalysis (and Ballard is nothing if not a committed reader of Freud), Ballard recognised that there is no ‘biological’ sexuality waiting beneath the ‘alienated layers’ of civilisation. Ballard’s compulsively repeated theme of reversion to savagery does not present a return to a non-symbolised bucolic Nature, but a fall back into an intensely semioticised and ritualised symbolic space. Eroticism is made possible – not merely mediated – by signs and technical apparatus, such that the body, signs and machines become interchangeable.

This is a slightly revised version of an essay originally published in k-punk on 1 June 2005. It is collected in Punk Is Dead, a new anthology from Zero Books which also includes essays and new writing from Judy Nylon, Dorothy Max Prior, Penny Rimbaud and Simon Reynolds. There’s a launch party for the book this Friday (20 October) at Rough Trade West – more details here. Siouxsie photo by Pierre Terrasson.