Even when observed through the emotionless glow of a computer screen, the photos framed within Silent Weapons’s ample negative spaces feel heavy. As if the energy emanating from the black and white snapshots of musicians frozen mid-motion was somehow transformed into mass. States of spiritual and physical rapture trapped for eternity. Combating the Deleuzian notion of photography as medium that destroys creativity and pacifies the viewer, Richard R Ross’s concert photos are provocative invitations. Here, the static becomes dizzyingly dynamic. Sifting through the book’s pages, narratives coalesce in time and space. Their protagonists – performers and audiences and spaces and ideas – flow into each other. From them, a call to action and a statement of intent emerge.

The Silent Weapons photo book, its title inspired by Milton William Cooper’s Behold a Pale Horse, is a multifaceted document. For one, it serves an archival purpose as it immortalises the impetus and first year of the eponymous concert series that the PTP imprint organised in and around New York City. Speaking from his home in New York, PTP label boss and musician Geng underlines this aspect, “the opposite of that preservation is erasure, it’s revision.” While still primarily a channel for the dark, ugly, and aggressive, but really beautiful and engaged experimental music of Dis Fig, Armand Hammer, YATTA, and Saint Abdullah among others, PTP’s mission has gradually grown beyond just the sonic, adopting an ardent activist stance.

As Geng puts it, “we should be doing things that give back to the neighbourhoods and communities.” So the artists and audiences worked together towards a common goal. The first four Silent Weapons shows in 2018 raised money for bail abolition organisations and immigrants’ rights groups, and collected books for library services at Rikers Island jail. “We’re realising the power that we as individuals and artistic community have with our voices and so called platforms,” Geng explains, “what happens if we come together, if we become useful in the socioeconomic and political climate that we’re in.”

While not directly intended to be one, Silent Weapons fulfils its second role by becoming a manifesto for localised action and mobilisation. It all started with Geng’s own Pain of Mind album under the King Vision Ultra moniker, a noisy amalgamation of hiphop and doom that is equal parts intimate confession and cure for systemic neuralgia. “I didn’t want it to exist as only an art project, to me it was more about actually putting in work on foot and making it work for others who are going through a lot of injustice.” Reflecting on the current state of the global music scene, he continues, “we don’t need this big budget, big platform bullshit, we don’t need these corporations with energy drinks and this other bullshit – we need to maintain control of what’s ours.”

From there, everything else followed. “That’s the point of the book, the series, the PTP ethos: a lot of people don’t have the privilege to be comfortable with the status quo.” While PTP communicates with listeners around the world and has recently expanded Silent Weapons beyond New York, the movements need to rise in local communities, and Silent Weapons is a blueprint for inclusion and diversity. “Showing that it’s possible is part of the goal of the book – this is happening, can be happening, and is attainable, and we are showing the representation of voices.”

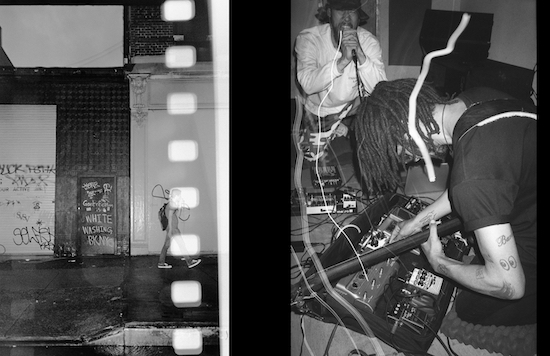

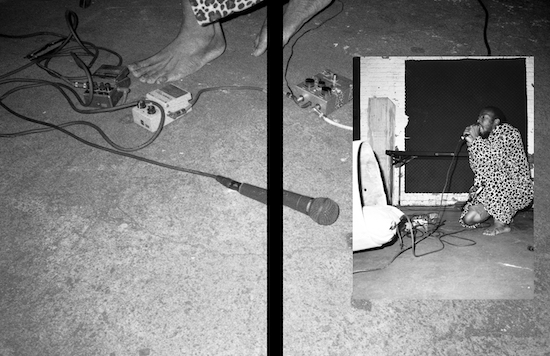

The book opens with an upside-down vista of New York before leading us through a sequence of pensive, relaxed photos from YATTA and L’Rain performances, mimicking their similarly reflective music. Then the mood changes as the queer nihilism of Dreamcrusher overwhelms and overflows the pages. Their body is on the floor, convulsed in a scream. The trail of light of a microphone traces their movements, splitting and joining the emptiness around them. Then during Violence’s set of glossy noise, Ross’s gaze descends below waistlines, capturing legs and feet in motion. Boundaries between people, the musician and the crowd, are erased. Looking at these pictures, stretched across two pages, you can hear the music’s deafeningly loud roar.

Where concert photography is often bland, pacifying reality in polished 4K resolution and projecting it through a voyeuristic, distantly bureaucratic prism; Silent Weapons is raw and spontaneous. Performers are rarely the centre of attention, instead they mesh with their contexts. Diffused images of crowds and spaces – a door tagged with “gentrification is white washing”, an exhausted man hunched over on a bench – are as important as those of musicians. Ross’s camera drifts around loosely to capture ephemerality and the intangible. It suggests rather than declares. A hand twists a knob. A scream takes form.

Within it all, Ross is an active participant, refuting any semblance of the objective observer. Geng calls him a “spectral photographer”, noting how “he catches energy and things that are floating in the sublime.” In that sense, Ross’s photography, while obviously informed by tradition, subverts and manipulates predefined patterns beyond the camera’s expected modes of use. “That’s what I call weaponisation, you weaponise traditional tools for your own needs, for self-preservation, survival, understanding, not just the physical vessel but what goes beyond, the unseen. That type of energy bleeds through these photos and definitely can be felt when you’re present in those spaces in those times.”

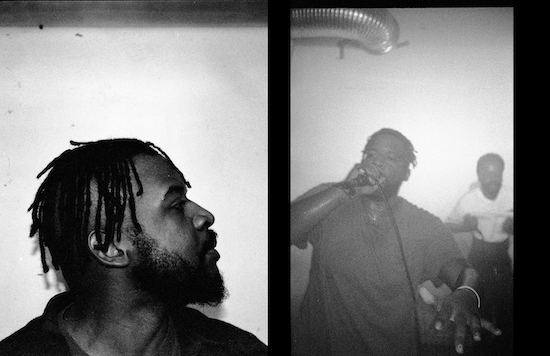

The images are positioned and laid out fluidly, accentuating their inherent symbolism and producing new meanings in mutual relationships. On the set during Greywulf’s concert, negative spaces around panels shape suggestive crosses. Armand Hammer’s Billy Woods explodes from a distorted, overexposed background like a deranged halo, his eyes blacked out, while a threatening closed-circuit television camera observes him from the adjacent photo. This composition is a deconstruction of the sinister object and implied culture of surveillance.

There is a methodological connection between the photos and the music of PTP artists. Talking about the importance of sampling in contemporary music and the similarity to Ross’s lens work, Geng explains “we challenge convention, we become wizards, we can bend, maximize, and minimize space, or change focus – sampling is a documentation, an archive, an alchemical kind of manifestation, you’re fucking with time in a crazy way, you’re taking something from an era and flipping it into something else completely, it becomes a bridge into this other narrative.”

The final photo in the book is then reserved for Felicia Chen alias Dis Fig. The New Jersey born, Berlin based musician clashes harsh industrial instrumentals and incisive vocals. Her anguished yet empowered stance transmits the rawness of emotion and theatricality of her latest album PURGE. It invites us to empathise with her story and to construct our own, around this and previous snapshots. This could be your town, your community, it tells us. This should be you, it directs us.

Silent Weapons is not a book to be revisited from a distance, from a tentative future. Silent Weapons is calling for action now. “It will continue on. That’s why I call it sustainable, it’s life work – it’s shit that doesn’t stop because it gets old. You can get tired and exhaust yourself, but as a mission there’s no set end goal.”

Silent Weapons is published by PTP