Poetry: In the last year it’s been either dead or new. It’s been either the sad end of the long running literary genre or the new rock ‘n’ roll. Or the new comedy. Or destroyed by spoken word. Or the new way to teach. Or stuck in a bygone era of dead white men writing about months, clouds, clocks and tigers. Or the new voice of youth. Or plagued by plagiarism.

The way some of the British media talks about poetry is very strange. I understand that editors like ‘angles’, but it sometimes feels like an article can’t be written about poetry that is just simply about poetry. Sure you get the odd review of the latest Faber, maybe a nod to a Bloodaxe collection – but it feels like poetry is not discussed without some squealing polemic declaring its rude health or newly rotting carcass.

I don’t profess an intimate knowledge of the poetry world, even though I have published poetry myself (through my imprint Influx Press), read a few contemporary poetry blogs and attend readings or spoken word events regularly. However, even without that involvement it’s pretty easy to see that parts of the mainstream media have no idea how to talk about poetry or how to write about its changing nature without resorting to exclamatory headlines.

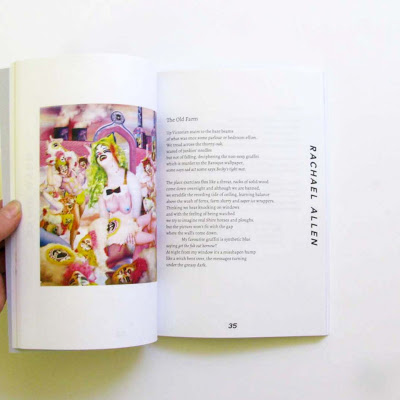

With this in mind, when I picked up a copy of Clinic III – an anthology of new poetry put together by south London platform Clinic – I felt inspired to write about it: I wanted to meet the editors and hear what they had to say about poetry and about their output. A straight article, old fashioned perhaps, but there you go.

Clinic have been doing their thing for a while now. Over the last three years they’ve been hosting nights around the capital, releasing pamphlets, anthologies and blogging fiercely. Clinic is run by poets Rachael Allen, Sam Buchan-Watts, Andrew Parkes and designer Sean Roy Parker. Their third anthology features some genuinely brilliant poetry.

The collection isn’t thematic, so it’s hard to say what it’s about per se: It feels more like a collection that is presenting a future of poetry. Not the sole future of course, but there is a sense that many of the writers feature in the collection could go on to be very successful, artistically. Some of them already are, Sam Rivere and Emily Berry for example – but they also featured in earlier Clinic releases before joining the Faber roster.

‘There’s never a theme with Clinic,’ says Sam Buchan-Watts, ‘we go to loads of readings and hear lots of different poets at different stages and ask some of those people to submit something for the next anthology. But it’s also a submissions process, anything we get is always looked at and considered.’

The book is organised on the basis of the poets, rather than the poems. Many of them have more than one poem in the anthology and this gives Clinic III the feel of having a number of mini collections within the book. Personally, I struggle with poetry collections that don’t pull together to present a discussion or idea. However, the poems in Clinic III are very well selected, so it almost passes me by. There is a political thread through the book, though. Not explicit, but it connects such poems as Nia Davies’s, ‘in the year ninety’:

‘we knew about saddam and maggy

and out out out

and oi,

we say no

to texaco,

the petrol blooms desert spooled through with black smoke

like our own sandstone flushed black

& the stained soil

in the field we called the park

we were for texaco

but

we weren’t for the war’

and Charlotte Geater’s ‘avoid using the word pussy’:

‘the trampled tents laughing

i hate i despise / the empty church

& do not respect

your festivals / what if we had two hundred thousand years more of this

& if you are not angry from before

these times / what riots

will you have had enough /stop

will you stop? pussy like most slang terms

(see also: cunt) an endearing name

for a girl / do not endear

when riots are / which anger is this’

However, Rachael Allen disagrees. ‘If the poem is political and it’s political unto itself, then that’s fine. But we’re not deliberately collecting political poems.

There are more political poems in III – but that might be just a reflection of the current climate.’ Rachel also fairly points out that, ‘themes can be quite dogmatic, we think very hard about the way collection is presented.’

In the Clinic Anthologies Sean Parker (not that Sean Parker – the anthology’s designer) is given all the selected poems as a bundle and it is up to him which order he places the poets (apart from the first and last). This is means the visual look of the poems are given due thought from a design perspective. I like this, it seems a fresh way of looking at poetry on the page. It lends a visual lucidity to the book, which matters. Sometimes poetry can be alienating when it is formed like

this

with spaces that may

meaning.

However, with a designer’s eye all over the book, it feels more accessible.

And Clinic III, like II and I before it is very accessible. Accessible in the sense that the poems have depth and emotion, but don’t obfuscate or confuse just for the sake of it. There is no pretention, no loftiness.

Rachael explains that this was part of their aim: ‘It’s really important to us to present as many types of poetry as we can. But the newest of those many forms. If we find we’re too heavy one way, we actively look to balance it out with something else. There are lots of late nights with us rowing about what poem should go in or not. But it’s so important to be accessible. From the beginning, we wanted to make sure that people who don’t read poetry, necessarily, can read this. So it’s the strongest of the batch of poets’ poems.’

A good example of this accessibility is Emily Toder’s short number, ‘A lot of Free Trials’:

‘A lot of free trials in conjunction should be

either prohibitively expensive

or one single free and lasting thing

This struck me as I continued

signing up my name on them

I had just heard word

It feels good to try something new

They had just come in with the news

I had just been my own posture

I mean my posture overcame me

I just let my posture overtake me

My torso bolted

Now if I don’t cancel this thing

within a month

I will have lost once again

in battle’

It’s very hard to imagine Rachael and Sam rowing. Sam is a laconic, laid-back man with a head of thick curls he constantly brushes away from his eyes. Rachael, by contrast, talks at bullet train speed sporadically interrupted by a loud laugh and a wicked smile. It’s clear that they favour different poems in the anthology but that makes for an interesting collection. I don’t like all the of the work in Clinic III, but I don’t think I’ve ever read an anthology, or multi-author collection in which I’ve loved absolutely every single piece. It’s inevitable that some will pass the reader by while others will speak to them very deeply.

In the last week I’ve been to four poetry nights out of seven evenings. Partly due to the Stoke Newington Literary festival, but also because, well… there are a lot of poetry readings and spoken word events going on in London. If there’s an environment to discover poetry it is the live arena and currently London seems to be the place live poetry is blossoming. In this tradition, Clinic started as a night out, combining music, art and live readings. It seems an important part of the Clinic identity:

‘It was always surprising in the first few events,’ Rachael says, ‘because we thought people would be coming for the music, but we’d get people at the door asking if ‘the poetry had started yet?’ We’ve been really lucky that they’ve go down very well. We let the poets have free reign. We say, you do what you want, have fun with it.’

After I suggest that performance is a strong part of poetry reading, at least in the spoken word scene with which I’m more involved, I’m swiftly rebuked: ‘We’ve never had a ‘spoken word’ event,’ Rachael says, ‘it’s always been inviting people saying – we like to read this, so we’d like to hear it too. If anything our poets are not performative in the way that they read. I like that, it feels like… they’re reading something truer to the page. Not that we’re for that page in that sense – I love to go to readings, I love hearing poems and I love to read out loud. But there’s no ‘style’ for the readers. We never worry if the readers are going to be bad, usually they’re just drunk. But we’ve never had a reading where something’s gone wrong with the poet.’

Sam tells me a story about one event they put on with a live Skype reading in collaboration with an American press called Ugly Duckling. One of their poets, Eugene Ostachevsky, even fielded a phone call from his mum during the reading. Even with the glitches in internet connection and interruptions the reading was a resounding success.

In Clinic III, there are a number of North American writers – more so than the previous anthologies. No bad thing, it even adds a strong burst of diversity to the collection. ‘In America they’re really making strides. There is so much out there. So much dialogue.’ Sam adds, ‘the criticism in America is just so much better. The national press reviews here often just read like blurbs. Publishing has become democratised. Loads of poetry is happening online which means it’s more easily available if you look for it. The old publishing models are breaking down, really slowly. And poetry is perfect for being read online because it suits that tiny window format – for example, [Sam Riviere’s] Austerities – that was on Tumblr to start with, it was wildly successful and perfect for that format. Online is where the readership is.’

Rachael cites her friend Harry Burke, who has <a href=” http://www.harryburke.tv/harryburke.html “ target=”new”>recently changed his website to become just drafts of poems as a google doc. ‘It’s this wonderful blend of experimenting with format, and with the poem at the same time. That feels perfect for an online space.’

Clinic certainly has a breadth and knowledge that comes from what could be seen as an obsession with poetry (‘We’re just nerdy. That’s it. We talk about poetry all the time, we read it all the time, we’re constantly sharing it’ – Rachael). The anthologies are impressive, well edited, well thought through and artistically innovative. As an editor myself I’m often curious about the thought processes that go on in selecting work for anthologies and the like. I ask Rachel and Sam what they look for in a poem and what is it that they see as necessary and relevant in poetry.

Rachael: ‘I’m into poetry that gives me a punch in the gut, emotionally. I started out by reading Sharon Olds and lots of confessional poets – and I was like, oh my god – blood, and women and guts and feeling. And it was only after I went to University that I began to theorise, and look at more complex poetry, language games etc. It becomes more critical then and you apply that sort of thing. But I think I still hold in my heart that I like to be punched in the gut by a poem. I like it to make me feel something. There’s a poem in Clinic III by Olly Todd that just makes me cry every time I read it.*

It’s very powerful and so concise. Ands he’s just managed everything in it so well. But at the same time I’m looking at things that are being experimental within the form, searching for something new, maybe something conceptual.’

Sam: ‘When I’m reading a poem, I’m looking for a kind of truth. It’s offering, to me, something that I know but have never recognised in those terms.

With some of the poems, it’s instant – this is incredible – but with others, they take some digestion. And a bit more labouring over understanding.’

Rachael: ‘Newness is absolutely necessary – in a way that your not replicating format. Or, if you are working within a format you have to be thinking about how that can be made relevant. Everything is changing. Context is changing all the time. There are new things in the world every single day and these things need to be worked with and made artistic. So if you’re going to carry on writing about love all the time, you have to write about love in a brand new way. For example, Harry Burke writes about heartbreak in a certain way, it feels very glib but it’s also really punchy and affective. It’s tight and quick and it feels like he’s rushing through heartbreak. Which feels new to me. Most poets dwell on it!’

Sam: ‘I think about Austerities in terms of newness because it’s in an old place to start as the book is a Faber publication. But… there’s such a concept involved: this sustained, insane register carrying through all 81 poems. But it’s totally subjective – what’s new for me might be old for someone else.’

There is definitely a big appetite for poetry in the UK. It comes in many forms and exists mainly outside poetry’s established spaces of production. At least, there is a willingness to entertain giving it a go amongst a lot of people now. I’ve lost count of the number of times someone has said to me at a poetry gig or spoken word event, ‘I’ve never really read poetry before, but that was great. So I might start.’ I can’t speak for everyone, but I’ve been surprised at the number of copies our poetry collections have sold and also that of other small publishers I know. Even then, as Rachael pointed out, it’s read online far more than anywhere else. She adds, ‘there’s no money in poetry, there never has been – but now the processes are more democratic it’s really burgeoning.’

Digital publishing has certainly changed the way small presses can afford to operate, for the better, and blogs, journals and collections online give poets far greater access to their audience. As Sam said, ‘there isn’t a gulf between the poet and the reader because the poem doesn’t exist without the reader.’ Therefore once the distribution gulf is reduced, poetry is reaching more and more people.

Clinic is doing a good job of keeping that accessibility open wide.

Perhaps one day in the future people will look to the anthologies as a classic example of contemporary poetry during our times. Maybe they won’t. But I’m definitely keeping the books as a record for myself.

(*) Harpists at the BBC

What you lost won’t be forever

Lost. It is simply a vanishing point,

a horizon the Greyhound driver’s

hand levelled at your brow,

a hack game in Girffith park –

the sack rasta colours and leaking

beads, losing weight with the sun.

It is things like searching stupidly

ovens for tupelos (or swamp trees),

falling, as airman, with grace to the sea.

It might be a letter shelf, fire grate,

Ray Bans, a photo of her dressing

harpists at the BBC.

Clinic III is out now, available at clinicpresents.com