Dave Hann, anti-fascist and writer, pieced together a collective history of anti-fascism that also re-defines political activity as participation in street protest rather than adhering to a party line. That history is Physical Resistance: assembled from his manuscript and completed following his death in 2009.

Physical Resistance is part of a culture of resistance, which has always included music and never more so than in the late 1970s:

One, two, three and a bit, the National Front is a load of shit…

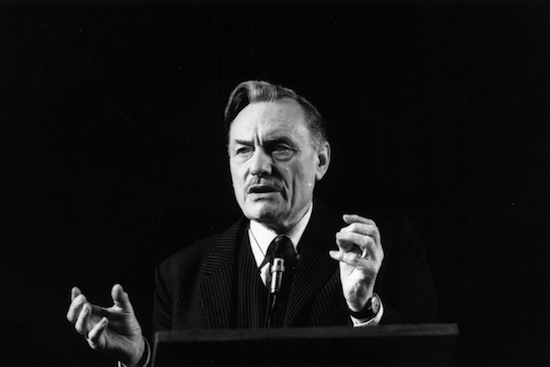

1976 was a busy year for anti-fascists. Rock Against Racism

(RAR) was launched in the autumn. The story is a well-known

one, but bears repeating. In August, Eric Clapton interrupted his

set at the Birmingham Odeon to advise his fans to ‘Vote for

Enoch Powell’ and ‘stop Britain becoming a black colony.’ In case

his audience didn’t get the full implications of his message,

Clapton expanded: ‘Get the foreigners out. Get the wogs out. Get

the coons out’ and repeated the phrase ‘Keep Britain White’. His

outburst prompted the photographer, Red Saunders, to write to

the New Musical Express, Sounds, Melody Maker and the Socialist Worker to remind the guitarist ‘Half your music is black. You’re

rock music’s biggest colonist.’ Saunders concluded his letter with

the declaration: ‘We want to organise a rank and file movement

against the racist poison music. We urge support for Rock

Against Racism.’

Clapton was unrepentant. He told Melody Maker the

following week that Powell ‘was the only bloke telling the truth,

for the good of the country.’ Maybe he was hoping that being a

rock star would immunise him from public opprobrium. After

all, Rod Stewart had made similar remarks without provoking

too much in the way of public disapproval and David Bowie,

whilst in a drug-induced haze, had declared that that Britain was

ready for a fascist leader and had ridden around Victoria Station

in an open top Mercedes giving a Nazi salute. The Bowie

incidents did create a brief furore in the press but the anti-racist

and anti-fascist movement had failed to muster any meaningful

response. Clapton’s outburst was the tipping point. The growing

anti-racist sentiment of a younger generation challenged both the

casual and the politicised racism of their elders. Hundreds of

letters supporting Saunders flooded into the papers. Within

months, Rock Against Racism (RAR) was born.

Blues singer Carol Grimes topped the bill at the first RAR gig

at the Princess Alice pub, East London, on 10 December 1976. On

the door were a group of dockers organised by Mickey Fenn,

Eddie Prevost and Bob Light from the Royal Group of Docks

Shop Stewards Committee. Fenn and Prevost had left the

Communist Party in 1972 and later joined Light in the International

Socialists. Stewarding RAR events was to become an important activity for

anti-fascists. Hundreds of gigs followed the one at the Princess

Alice. The RAR movement was sustained by the energy and effervescence

of the punk rock explosion. Punks loudly rejected the

self-indulgent musings of the earlier generation of ageing rock

stars. Their opposition to the musical establishment was part of a

wholesale political rejection of an old order. RAR platforms

reflected the anti-racism of punk and brought together bands that

wrote songs about disenchantment of a white working class with

reggae musicians whose lyrics expressed the desire for freedom

of African peoples. The manifesto set out in the first issue of

RAR’s magazine, Temporary Hoarding, demonstrated the

optimism of the movement’s founders, including Ruth Gregory,

Roger Huddle, Red Saunders, Syd Shelton and Dave Widgery. It

expressed their belief in the power of music to create political

change:

We want rebel music, street music. Music that breaks down

people’s fear of one another. Crisis music. Now music. Music that

knows who the real enemy is.

Rock against racism.

Thousands of people got involved in RAR. One who threw his

hat into the ring was John Baine, now better known as Attila the

Stockbroker:

I went to Kent University in the mid Seventies, just at the

beginning of punk. I got involved in Rock Against Racism.

RAR had been formed to counter a shift to the right in the

music scene, which was epitomised by some rather crass and

reactionary comments made by David Bowie and Eric

Clapton. Coupled with this was the worrying rise of the

National Front, which by the mid to late Seventies was

beginning to look really dangerous. I was also involved in the

music itself as a punk bass player before I became Attila the

Stockbroker in 1980. A group of us got together at Kent

University and started up a local RAR group. We organised

gigs, we sold badges and stickers and ordered loads of copies

of the RAR fanzine Temporary Hoarding.

It would be difficult to underestimate the importance of RAR. It

did more than swell the ranks of anti-fascists. A few key RAR

organisers were International Socialists, soon to re-name

themselves the Socialist Workers Party. The relationship between

RAR and SWP helped the Trotskyist movement to become an

increasingly important force in the battle against the NF.

Local anti-fascist committees were also growing in number

and membership throughout 1976. The launch of one in Brighton

was attended by 70 people. Tony Greenstein describes its political

composition:

It was chaired by Rod Fitch, a Prospective Parliamentary

Candidate in Brighton Kemptown for Militant and the Labour

Party and it used to meet at the Labour Club, 179 Lewes Road,

in the basement. I was one of those who were in the far left,

direct action, part of the opposition in the anti-fascist

committee, along with the SWP/IS and students and IMG as it

was then. There were trade union delegates and a couple of

people from AJEX, who we didn’t get on with. The Anti-

Fascist Committee leafleted the whole of Brighton.

Differences and divisions in the anti-fascist movement over the

acceptable forms of resistance, peacefully opposing the NF or

physically stopping them, did not disappear with the optimism

of RAR or the growth of the local committees. Both strategies

were pursued as the movement continued to expand. Fascist

violence, such as the involvement of NF supporters in racist

attacks in East London towards the end of 1976, increased the

militancy of anti-fascists.

On Saturday 23 April 1977, the NF tried their hand at intimidating

The North Londoners that lived in and around Green

Lanes. They assembled at Ducketts Common to march to

Palmers Green. The pattern of opposition will be familiar.

Religious leaders, local dignitaries, supported by members of the

CP held a counter-protest while the International Socialists/Socialist Workers Party, the International Marxist Group, Labour left-wingers, anarchists, members of the Indian Workers Association and local youth from the West Indian, Turkish and

Greek communities assembled away from the official rally. In

numbers equal to those that listened to the speeches, they lay in

wait for the NF. When the NF reached the junction of Westbury

Avenue and Wood Green’s High Road, the march came under

sustained attack. It was subjected to a barrage of missiles,

including marine flares, paint bombs, flour, eggs, rotten fruit and

every single shoe from the racks outside Freeman Hardy and

Willis. Fights broke out. The march, protected by a large-scale

police operation including the Special Patrol Group (SPG),

buckled but did not break. Eventually, those fighting to stop the

NF were cordoned off. The shaken NFers regrouped and

continued with their march to be harried the rest of the way by

the remnants of the militant opposition. There were 81 arrests, of

which 74 were anti-fascists.

Physical Resistance: A Hundred Years of Anti-Fascism is out now, published by Zero Books

Follow @theQuietusBooks on Twitter for more