Peter Buwalda is an enviable concoction – tall, charming, humble, talented and successful. But, while the first four presumably hold true universally, the latter is yet to be proven in the UK at least. When Buwalda’s debut novel, Bonita Avenue, was first published in his native Netherlands (where he’s known not only for his fictional contributions, but also as founder of the literary music magazine Wah-Wah) it cleaned up commercially and critically, with impressive sales figures and winning a whole host of literary prizes. As we sit down in a well-know chain chocolaterie – for which Buwalda will later express a fondness while crunching loudly and enthusiastically on a confectionary rabbit’s head – I acknowledge that this must be difficult for him and he shrugs. It’s just how things are, he says: no one knows him yet in England and he has to do the rounds. He doesn’t mind. He’s grateful to everyone – he just wishes he had more time to actually write. But it’s a hard slog, I’m sure.

That being said, I’d also be willing to bet it pays off. Not so much thanks to any kind of intensive publicity schedule, but for what you’d probably call "the right reasons": Bonita Avenue is an excellent book. It’s a two-pronged coming of age drama – a personal and social bildungsroman – charting, both, the dramatic advent of a young woman’s sexuality, seen through her eyes and the gaze of the two influential male figures in her life (her boyfriend and grandfather) and the seemingly-meteoric rise of internet pornography, inextricably bonded through a single narrative arc.

Buwalda’s prose, in their glorious, near-melodramatic minutiae seem to presuppose contemporary internet culture even as his narrative convulses with the early stages of its gestation: democratisation of information, invasion of privacy, the digital flaneur and voyeur all throb under the surface of Bonita Avenue. But so does a more recognisable conflict, ages old and relevant now as it has ever been, if not more so: the generational divide, the difference between and inevitable supplanting of the ideologies of the father with those of the child. It’s fiercely observant without ever seeking to occupy or define the moral high ground – a novel as primal as it is contemporary.

Your writing is quite detail heavy – is that something you think has transferred quite well from writing non-fiction to writing a novel?

Peter Buwalda: No, because in practical terms when you use a lot of detail then you use a lot of space. It’s a thick novel and I was used to have to compress the stories that I wrote. It’s totally different; it’s a different way of writing.

There’s a long history of journalistic and essayistic writers overlapping in to fiction – two of the most notable being Orwell and Hemingway, I guess – and on the back of Bonita Avenue you’re compared favorably to Jonathan Franzen. Was that something you were happy with?

PB: I’m not the sort to make comparisons my self, I don’t like it that much, but I’m an admirer of The Corrections for instance and he was writing Freedom when I was writing my novel. Freedom was not so convincing as The Corrections, but my novel doesn’t resemble The Corrections so I don’t know why they’d say that. But I’m flattered, of course – he’s one of the more important American writers of Today.

He recently wrote a piece about how the Internet is affecting us a society and how it has impacted publishing and “being” a novelist in general – the good people at Slatehave kindly put together a representative juxtaposition in “the quiet and permanence of the printed word,” which “assured some kind of quality control,” versus “an apocalyptic hellscape punctuated by “bogus” Amazon reviews and “Jennifer-Weinerish self-promotion.”” – is that something you’ve experienced at all?

PB: I’m used to it. He started writing before the Internet and I’ve only written while it’s existed – but I was around before. I’m not so happy with Facebook, for instance, or Twitter. For a writer especially what has changed is that feedback has exploded: there are so many responses you can find on the internet – websites like Goodreads as well as the two I just mentioned. That has some good points, I think. Drifting away from the reader is not happening so easily anymore. There were times when writers – you know, in the postmodern days, people like Pynchon – weren’t aware of people who have to read the crap you’re writing. And now we are. Thanks to the Internet.

Do you read the feedback at all?

PB: Yeah, I read it. And the interesting thing about it is that the numbers of feedback is so big that you can see a kind of average. I’ve noticed that every novel that’s reviewed on Goodreads, for instance, gets a certain rating, let’s say, 4.12 stars and it stays like that for years. There’s a bell curve of reaction. It’s soothing – it gives you a little peace. But I try to keep a way from it to a degree – one of the things that I experienced from all the reactions is that they’re conflicting. There are people who say ‘the start of your novel is a little complicated but I loved the end,’ and someone else will say ‘I loved the start but I hated the end,’ and they both gave three or four stars. I just learned that you can’t make anything that everyone will like for the same reasons. My conclusion is that you have to make something that you like yourself – but maybe now I sound like Pynchon.

That’s another thing that’s different from journalism, I suppose, in theory there’s no brief here – no ‘target audience’ dictated from an editor up on high before you’ve even started to write…

PB: Exactly: I invent my self as my favourite reader. If you gave it to me – if you recommended my novel to me – and if I like it then I’ve succeeded. Maybe that’s the only way to survive in this new world of responses.

It’s not entirely removed from that, then – the idea of this mass of entirely accessible information – that the main conflict in the novel occurs essentially because one of the three main characters discovers photographs of his daughter on a pornographic website.

PB: Yeah, one of the main thoughts I had starting writing the novel was not precisely this problem, but a generational conflict, I think – albeit one that is resolving because the Internet Generation is getting older. But at the moment, in the time the novel is set, we have this satiation that younger people, let’s say grandchildren, sat on their grandparents’ lap are wiser or more-knowing – about things like porn, sex, other women, other men – than the grandparent. That’s for the first time in history, I think. When I was a kid I could swear that my father or my grandfather knew more about sex than me. But that just isn’t anymore – and that’s interesting, conflicting and even disturbing for some people. That’s what I try to depict in the novel: it’s not so much a case of issues of privacy, though that is important, of course but of differences between the ages.

Do you consider the novel to be critical of this – “New World Order” seems like large-scale hyperbole – what feels like a change in the traditional familial hierarchy?

PB: I hope that the moral side of the question is spread out over different voices – that’s why I chose to have the three main characters as opposed to a single protagonist – between people who haven’t the slightest problem with porn on the internet (Joni, the daughter), people who are very concerned (Sigerius, the father) and somebody who is in the middle (Aaron, the photographer). What’s important is that joni wants it – she thinks it’s okay, and she thinks it’s clean – she’s hiding it because she’s not so sure about her environment. Of course I have my own standard, but it’s not in the novel.

It’s not a morally critical novel, but maybe it is a critique of that shift in family paradigm and technology in this instance exacerbates the situation. It could still have occurred to some extent in a previous time with, say, polaroids but because this is on the internet there’s no damage limitation – it’s all out there for anyone and everyone.

PB: One of my presuppositions was that the Internet has multiplied the cases: there is a lot more content than there was before. One of my thoughts was that every nude picture on the Internet is a Trojan horse – it contains within it a family conflict. Somewhere it has to go wrong: you can’t let me believe when a girl the age of 20 makes a pornographic movie that her entire environment will agree with that choice. There will always be somebody who doesn’t – a person in the company where she works, or her brother or a friend.

Nothing happens in a vacuum.

PB: It’s like plastic. When you throw away a plastic package it stays there for ten thousand years. One of the interesting things, also, is that the dynamics of the Internet – of internet porn – are so fluid: things change by the year, almost. Right now we’re talking about it all so freely, on such an abstract level, but when I was writing I had never said the word porn before. It’s a really quick evolution.

When I started writing another one of my starting points was the idea that it was a kind of public secret – and at that time it was. In that sense the novel will be ageing – but which novel won’t? – not the topic itself, I hope that will still be interesting, but that part of it.

It’s integral to the story in a narrative sense, having a photographer in the middle of the whole thing, but what role does the camera play in the novel as a device – other than just literally in taking the photographs? The idea of the voyeur.

PB: I think from the perspective we have now, the camera has made a tremendous impact and it gets more important or at least more prevalent everyday – just look at the “selfie”. In those days, even though it wasn’t that long ago, when I was writing, it wasn’t as big so when I was writing… I hadn’t had a real metaphorical thought about it: I just needed somebody, Joni needed somebody, to take those pictures. For me what’s more interesting is that her love for Aaron, her interest in Aaron, isn’t that clear – whether it’s for his photographic knowledge, or whether she actually likes him. She doesn’t know it herself, in the end – they’re so stuck in that business of theirs, making that money, that she loses sight of her real motives.

She’s not a victim at all, in that sense – or any sense, really. Is that something you thought was important – to have a female character that wasn’t in any way a sub-character or subordinate?

PB: Yeah, for a start I wanted to make her funnier than Aaron. She makes the jokes. That’s one of her strengths. But her main strength is that she makes the decisions – she decides for her self that she wants to be on camera, to be on the internet, to make all this money. I wanted to avoid the patronising cliché that no woman would do this willingly. Part of writing a novel is to stay out of the clichéd – it would have been too easy to make her a victim.

There are women who are in control, but of course there are also women who aren’t and I don’t want to generalise – I chose to go that way for this story. The novel isn’t intended to say something about everybody, it’s peculiar to this situation. I created someone is clever and who is strong and who sees money, who wants money and who finds a way to get money for her self without getting her hands dirty because nobody touches her. She has a very sharp conception of what it is she’s doing.

Physical description is part and parcel of setting up a character, but I noticed that you really home in microscopically on specific body parts – it reminded me of Murakami’s ear fetishism initially…

PB: Well, I’m not “interested” in ears in that way, but I focused in on his ears because it was important for me to make clear from the first pages that Sigerius – the main protagonist – is of two worlds: yes, he’s a professor, an academic, but he’s also a very physical guy. Real physical guys – Judokas or boxers – they all have their mutated physical elements. And Judokas in particular, the best ones, they have cauliflower ears. It gave me a chance to show immediately that’s he’s a rare person in that sense – he’s not belonging to any one of the social layers that he’s supposedly a part of.

I started my self in physics. But I was on two paths – I had a two-track mind. I loved literature very much, but I also loved exact sciences. I was good at both, but then literature was more tempting and so I quit the sciences after six weeks.

They’re massively different, but there are similarities between the two – they’re both driving at the same sort of thing, they’re posing and answering questions like ‘How’ and ‘Why’ things happens just on a different scale.

PB: They’re both getting at something, yeah. And they both have certain aesthetic qualities – Sigerius gets emotional when a piece of math is elegant. A real mathematician can be emotional; they can be an artist. I interviewed some mathematicians about their work and they speak about it like somebody who speaks about Lionel Messi.

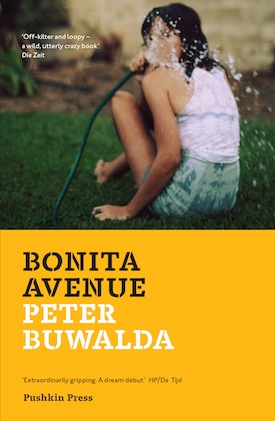

Bonita Avenue is out now, published by Pushkin Press. Author photo by Victor Schiferli