In ‘Ritual Music for the Accumulation of Energy’, a 2014 article for The Quietus, Jimmy Martin interviewed the London-based solo musician Anji Cheung. During the conversation Cheung discussed her influences, including such interrelated artists of the ‘Hidden Reverse’ milieu as Throbbing Gristle, Coil and Cyclobe.The article also looked at Cheung’s album-length piece, ‘Oakseer’. Recorded in 2013, the track is composed of slowly building noise, looped ceremonial samples and layers of guitar. As befits the druidic connotations of its title, ‘Oakseer’ is intended to act as a kind of audiophonic spell or, as Martin puts it, a “ritualistic serenade”, one that opens “murky portals to dimensions unknown”. Offering a further gloss, Martin adds:

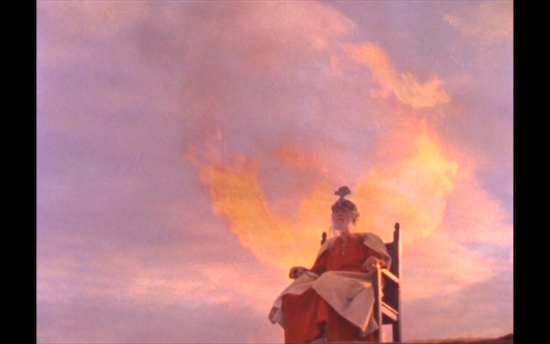

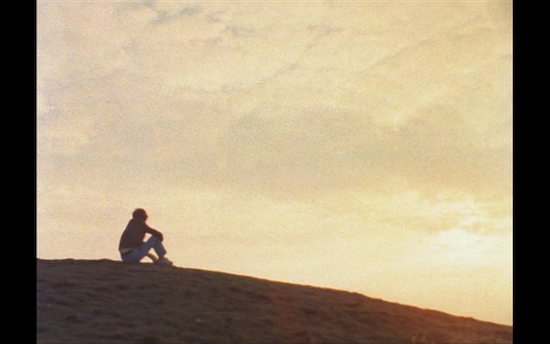

‘Oakseer’ in particular summons a peculiarly British kind of bleak and wyrd eccentricity, not in itself a million miles from the recent work of English Heretic, from the visual spell-casting of [The] Blood On Satan’s Claw, Penda’s Fen or The Wicker Man, or from the cosmic horror of Nigel Kneale and the work of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop.

As a critical act, there is certainly nothing unusual about the attempt to evoke, for the benefit of one’s readers, the tone of a high concept piece via a royal flush of additional reference points. Like reaching for a convenient tarot pack, this micro-catalogue helps to bring out the essence of the work under discussion and, crucially, helps to inform the reader whether they are going to like it or not. It is not unlike asking Cheung to identify some of her own influences. That said, in contrast to the sequence of interconnected musicians she cites, all of whom could be said to occupy a similar artistic territory, Martin brings to the fore a peculiarly wide range of reference points when describing ‘Oakseer’, the single work under discussion.

The examples offered are cross-formal and trans-historical, and across the paragraph above, the reader encounters contemporaneous recording artists like English Heretic; 1970s film via reference to Piers Haggard’s The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971) and Robin Hardy’s The Wicker Man (1973); 1970s television by way of Alan Clarke’s Penda’s Fen (1974) before reaching a seemingly associated writer in the form of Nigel Kneale and, most anomalously in terms of its formal difference to the other examples cited, a department of the BBC in the case of the closing reference to the Radiophonic Workshop. The latter two examples appear to signify yet more lines of implicit connection unspoken in the text.

Kneale was the author of the Quatermass series that had television and film incarnations between 1953 and 1979. He also wrote The Stone Tape (1972), a television film directed by Peter Sasdy that linked supernatural phenomena to architectural resonances. These ideas as well as concepts used in Quatermass and the Pit (1959 / 1967) reflected the work of the archaeologist and dowser TC Lethbridge who, in his book Ghost and Ghoul (1961) proposed a theory of paranormal phenomena that became known as ‘residual haunting’ or, more colloquially, ‘The Stone Tape Theory’. Meanwhile, citing the Radiophonic Workshop invariably brings to mind Doctor Who, the series which requires no introduction other than to say that it has often covered similar themes to those dealt with by Kneale. More specifically and with greater relevance to Cheung’s work, mention of the Radiophonic Workshop brings to mind the pioneering electronic musician Delia Derbyshire who arranged the now iconic Doctor Who theme. Compressed into Martin’s brief survey, these potent references are combined with an underlying sense of magical practice, underground culture and national identity. A heady mixture. And yet, despite the thematic and formal variation at play, the signposts all seem to work. I get it. A field, it seems, is mapped out. And there, in the middle, is the subject of the present volume: Penda’s Fen.

In ‘The Field of Cultural Production’ (1993) Pierre Bourdieu argued that an understanding of “literary production” requires a “relational approach”, one that departs from modes of thought which tend “to foreground the individual” and which highlight instead “the structural relations” between “social positions that are both occupied and manipulated by social agents”. Bourdieu was concerned not with the fetishism of “‘great men’, unique creators”, but with the matrix of competing forces that surround and constitute a given ‘work’. This ‘field’ involves matters of genre, linguistic context, contexts of production, distribution and readership as well as the infrastructural “institutions” that permit access to the work: journals, publishers, reviewers. For Bourdieu, the persistence and resonance of a given work – its relative access to cultural capital – is dependent on an act of “artistic position-taking”: the traction gained by a work-as-agent within the field of “forces” and “struggles” – often deeply hierarchical – that constitute the literary or artistic field as a whole.

Consciously or not, when Penda’s Fen appears in Martin’s article, it does so as an artistic agent in the sense understood by Bourdieu. It assumes a position that calibrates the critical and definitional work of the discussion conducted. It helps shed light on ‘Oakseer’ and position it within a relational grouping. For the record, ‘Oakseer’ is rich and rewarding enough to warrant such comparisons and it certainly does not suffer from being placed in relation to Penda’s Fen. But we still might reasonably ask about the specific agency of the name. Placed amongst a powerful but somewhat familiar pantheon, what type of force does the name Penda’s Fen exert?

When approaching the task of critical evaluation, it seems fitting to focus on the distinctiveness of Penda’s Fen: its uniqueness. It can easily be read as a ‘classic’ in the sense understood by T.S. Eliot. In his essay ‘What is a Classic?’ (1944), Eliot argued for ‘maturity’ as the key criterion of a work’s classic status. The classic, he posited, “can only occur when a civilization is mature; when a language and a literature are mature; and it must be the work of a mature mind.” Further, it “is the importance of that civilization and of that language, as well as the comprehensiveness of the mind of the individual poet, which gives the universality. What the current re-appraisal of Penda’s Fen indicates is that the film stands as a similar work of artistic maturity: a text that exceeds comparison, stands apart from parallel works and pushes at the limits of its content and form. In the light of such a trajectory, naming the film as part of a sub-genre of sorts, could be seen to blunt its singularity. This is very much the point made by Graham Fuller in his 2017 essay on Penda’s Fen, ‘In Quest of the Romantic Vision in British Film’:

[…] Penda’s Fen is often lumped with ‘folk horror’ or folkloric movies and television dramas of the late 60s and early 70s: Whistle and I’ll Come to You (1968), Witchfinder General (1968), The Owl Service (1969-70), Robin Redbreast (1970), The Blood on Satan’s Claw (1971), The Stone Tape (1972), The Wicker Man (1973, a virtual son of Robin Redbreast) and Red Shift (1973); contemporary equivalents would include Ben Wheatley’s Kill List (2011), partially, and A Field in England (2013). Yet none of these works has the religio-philosophical reach or political urgency of Rudkin and Clarke’s masterpiece.

There is that distinction and maturity. In its ‘reach’ and ‘urgency’, Penda’s Fen stands apart from the competition: a ‘masterpiece’.

One can readily agree with Fuller’s assessment and it is reasonable to expect critical discourse to posit the non-generic as a marker of value. That said, generic groupings come together for a reason. Field boundaries, one might say, are expressive. As such, then, rather than continuing to speak about Penda’s Fen in terms of its exceptionalism, my interest lies in the work done by its name when invoked and placed in such groupings. Clearly, the content of Penda’s Fen is deeply, deeply symbolic, but what work does the film do when taken as a symbol? What does it stand-in for when cited in commentaries regarding seemingly comparable material?

To posit an answer, it is worth considering another example, one that will likely be familiar to anyone interested in Penda’s Fen and seemingly proximate works: a passage from Rob Young’s book Electric Eden (2011). This study of “England’s visionary music” starts with a description of a screening at the British Film Institute. Young attends an evening curated by the English Folk Dance and Song Society that includes a series of pre-WWI films by folklorist and collector Cecil Sharp. Towards the end of the book Young describes another event, an evening of film and music organised by the “boutique record label Ghost Box”. Here, we are told that DJs play a “strange brew of samples from sources that rarely seem fashionable: cocktail jazz drums, Hammer horror movies, synth burbles from Open University lectures”. Although it is heavily implied that the musical and visual languages in evidence in each instance are very different, the suggestion is that these events are intended to book-end the narrative of Electric Eden. They point to a line of spiritual inheritance. Cecil Sharp working in the early to mid-twentieth century and Ghost Box in the twenty-first, both appear to be interested in the idea of a ‘hidden’ England and, in the work of the latter, Young sees a useful departure point to survey a wider cultural field:

In the opening decade of the twenty-first century, there are a surprisingly large number of musicians, working underground, churning out similarly haunting and disquieting sonic fictions that chime with the notion of an alternative Albion […] There’s even a shadowy collective calling themselves English Heretic who undertake psychogeographic walks to install ‘black plaques’ at sites of occult significance, such as the grave of Witchfinder General director Michael Reeves.

From these sonic elements the DJs are spinning an impromptu soundtrack to cult 1970s TV such as Children of the Stones, The Stone Tape and Penda’s Fen.

Again, the unholy trinity are present and correct: Children of the Stones, The Stone Tape and Penda’s Fen. With the worthy and necessary addition of English Heretic, Young marks out virtually the same map as that drawn by Martin when discussing Anji Chueng. However, there is more going on in this marshalling of cultural references than a general approximation of a haunting or otherwise haunted musical climate. Young describes how “these sonic elements” are being used re-iteratively; to re-soundtrack the likes of Penda’s Fen. In addition to creating a distinct sense of connection – if not dialogue – between the material of the 1970s and that of “the twenty-first century”, there’s a pervasive sense of simultaneity running through the paragraph. The image of the DJ mixing and re-mixing moves away from notions of lineage and influence and instead suggests that each of the works cited collectively inhabit the same territory. The issue is not that of arranging works as part of an historical continuum but one of highlighting instead the persistence of a shared sensibility or even a collective paradigm.

One might note also that Penda’s Fen is the third and last in the passage’s short sequence of, as it were, ‘classic’ examples, a list which is not arranged chronologically. Young offers “Children of the Stones, The Stone Tape and Penda’s Fen”, when The Stone Tape was the earliest, first broadcast in 1972, followed by Penda’s Fen in 1974 and then Children of the Stones which appeared in 1977. Coming at the end of the sentence, out of temporal phase with the other works cited, Penda’s Fen establishes an implicit hierarchy in the sequence. Whether this was Young’s intention or not, when reading passage, one’s attention is ultimately draw towards the name Penda’s Fen, as if it functions as the point of gravitation for the other examples: the texts that all the others look towards.

As regards the specific sensibility made manifest by this use of the title, it is foregrounded in Young’s reference to a contemporary cultural ‘underground’, a milieu he connects to an interest in “sites of occult significance”. One might better call this ‘occulture’, a word used here not as a convenient coinage but with a specific reference point in mind. In an introduction to one of the later editions of his fanzine-cum-journal Rapid Eye (1979-1997) the late Simon Dwyer used ‘occulture’ to describe his signature interest in music, politics and the occult:

Occulture is not a secret culture as the word might suggest, but culture that is in some way hidden and ignored, or willfully marginalised to the extremities of our society. A culture of individuality and sub-cults, a culture of questions that have not been properly identified – let alone answered – and therefore, do not get fair representation in the mainstream media. It is a culture that has been misinterpreted. […] It is a sub-culture that is forming a question that ‘reality’ alone cannot answer.

This was a fair summation of the topics Rapid Eye covered. In a typical issue one could find articles on Genesis P. Orridge, Kenneth Anger and Derek Jarman, sitting alongside discussions of mind control, UFOs and psychedelic drugs. One could equally take Dwyer’s description as an unconscious summation of Penda’s Fen. In the film’s overt embrace of chthonic energies, it departs from the likes of Children of the Stones and The Stone Tape insofar as the drama’s occult elements are not a trap, not that which is to be escaped from or that which thwarts an attempt at escape. Instead, the narrative is one of conversion. It charts “the slow formation of a question that reality alone cannot answer”: what lies beneath, why has it been buried and how can it be revivified?

Inserted into commentaries and analysis, it is this occultural perspective that Penda’s Fen and specifically the name Penda’s Fen is used to signify. It offers a shorthand for work that triangulates landscape sensitivity, visionary consciousness and radicalised creativity. This is precisely what we see in the work of English Heretic, the artist who has shadowed the citations considered thus far. Across his decade-long excursus into the dreamtime, English Heretic has effectively acted as Stephen Franklin’s field agent. The project – in the form of music, writing, video and visitation – has mapped out, excavated and amplified the psychic leys embedded into the country’s sediment.

When Young speaks of English Heretic undertaking “psychogeographic walks to install ‘black plaques’ at […] the grave of Witchfinder General director Michael Reeves”, he is referring to a specific, early iteration of the project. This was described by English Heretic in the essay ‘Locus Terribilis’, published as part of the book, The New Geography of Witchcraft (2005):

The idea for creating a black plaque CD and placing it at a symbolic location was influenced by the terma tradition of Tibetan Bon Buddhism. A terma was an object secreted in a rock, buried in the ground or lodged in a tree. These were hidden teachings that were intended to be discovered some time in the future. They were a way of passing on wisdom, partly necessitated by the persecution of openly practicing Buddhism. The future recipient of the terma was known as a tertön. Applied to the Black Plaque project, the tertön was the future creative self, though I sometimes wonder if a groundsman at Ipswich crematorium is the spiritual heir of my conceit.

This time-capsule approach explicitly creates that which is occult, i.e. hidden, as a means of inspiring generative acts to come. Pitched in the shadow of historical persecution, the act also speaks of the political efficacy of that which is dormant: held in stasis, the terma awaits its re-discovery as both a marker and herald of political change. Like ‘The Buried Jesus’, this English Heresy is one that acknowledges the superficiality of the status quo and is prepared to draw upon that which lies deep. As with Penda’s Fen it is a powerful message and one that is very much relevant.

During the 2017 General Election campaign in which Conservative Prime Minister Theresa May attempted to cement the hegemony of her premiership, she was interviewed by Julie Etchingham for the ITV programme Tonight. May thankfully lacks both the condescending horror of her oft-cited doppelganger Margaret Thatcher and the Oxbridge braggadocio of her predecessor David Cameron. The result, however, is a kind of crushing normalcy which makes the problematic nature of her views all the more disturbing: her one-nation Conservatism is constantly served up to the public like common sense advice from an uninspiring school teacher. A classic moment came when Etchingham, towards the end of the interview, asked May something of a leftfield question, “What’s the naughtiest thing you’ve ever done?”. When compared to Jeremy Paxman asking Cameron about gynaecologically-themed cocktails served in the bars he used to have a stake in, this is perhaps not the most difficult of questions. That said, May struggled to respond:

Theresa May: Oh, goodness me. Well, I suppose… gosh. Do you know, I’m not quite sure. I can’t think what the naughtiest thing […] I have to confess, when me and my friend, sort of, used to run through the fields of wheat. The farmers weren’t too pleased about that.

Occasionally running through fields of wheat: when the history of transgression is written, it is unlikely that the details of May’s childhood in Sussex will warrant much of a mention. That said, while it is easy to mock an awkward interview (particularly considering the lacklustre election performance that followed), May’s sedate image of rebellion invites some pause. It carries with it a stark inverse, her imagined and implied ideal of how the English landscape should be: pristine uninterrupted fields; farmers knowing their place; a Country Life landscape free of any disturbances; migrant workforces either wholly absent or at least pleasingly out of sight; a landscape open to occasional escapist forays but only to the children of parents rich enough to afford converted barns lying at the field-edge.

May’s party have form when it comes to such social and geographic conservatism. In 1994 Michael Howard, then John Major’s Home Secretary, introduced the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act. A sweeping supplementation of the existing parameters regarding the remit of “the criminal law and powers for preventing crime and enforcing that law”, the Act was widely opposed and derided for its antipathy towards the public performance of music that contained “repetitive beats”. More seriously, the Act constituted a wholesale attempt to expunge certain subcultures and adherents of ‘alternative’ lifestyles from sites previously recognised as “common” land. The criminalisation of “repetitive” music was part of a rear-guard action against the burgeoning rave culture of the 1990s and was shored up by the Act’s tightening of legislation regarding collective trespass, “nuisance on land” and squatting. It was not just raves that were affected. Protest actions, particularly those directed at fox-hunts also came under the sweep of the Act. Similarly, the withdrawal of grant provision previously afforded to local councils to provide space for traveller camps also pushed this traditional nomadic culture further into the category of “unauthorised” camping. Not in my back-yard.

One recent text that presents a response to this ideological construction of the English landscape is Jez Butterworth’s play Jerusalem (2009) that features as its central protagonist the ex-stunt man and local ‘character’, Johnny ‘Rooster’ Byron. Byron lives in a caravan at the edge of a village modelled on Pewsey in Wiltshire. It is set on St. George’s Day which, in the play, is also the day of the local Flintlock Fair. In addition to detailing Bryon’s interactions with the other village locals, both hostile and affectionate, the play’s jeopardy is also based around the threat of the local council serving him with an eviction notice. Jerusalem reaches its climax with Bryon – physically beaten and duly served with said notice – rallying himself with a type of curse, a monumental, tub-thumping invocation of folkloric entities and strange children:

Johnny ‘Rooster’ Byron: Rise up! Rise up, Cormoran. Woden. Jack-of-Green. Jack-in-Irons. Thunderdell. Búri, Blunderbore, Gog and Magog, Galligantus, Vili and Vé, Yggdrasil, Brutus of Albion. Come, you drunken spirits. Come, you battalions. You fields of ghosts who walk these green plains still. Come, you giants!

Butterworth wisely leaves it unclear as to whether the spirits respond to his call. Either way, that Bryon marshals a folk tradition as a countercultural technique; a means of disobeying and confronting the legislative forces that oppose him, keys directly into the central message of Penda’s Fen. Byron literally and symbolically stands his ground by calling on the sacred demons of ungovernableness specific to his locale and regional history. Read in light of the discourses emerging from Theresa May’s government, and indeed the wider context of Brexit and its divisions, the power of Bryon’s clarion call can also be found in its defiant heterogeneity, its focus not just on English folklore but the extension of a territory that is radically European. If the current focus on Penda’s Fen and other works of occulture is to be taken as in anyway indicative of a contemporary zeitgeist, then it is perhaps because a sense of this strategic spirit – ‘real’, imagined and folkloric – is ever more necessary.

A Penda’s Fen Sourcebook: Of Mud And Flame, edited by Matthew Harle and James Machin, is published by Strange Attractor Press. There will also be a launch event for Of Mud & Flame at the Whitechapel Gallery on Saturday 29 February