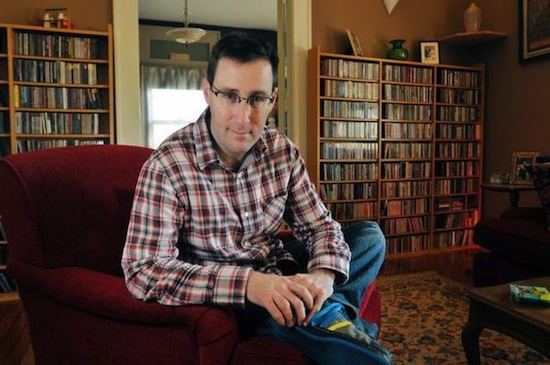

When Jeff Jackson’s agent submitted the manuscript for Mira Corpora to me at Two Dollar Radio, it immediately stuck out: it arrived accompanied by an endorsement from Don DeLillo. That is something, as an editor, you don’t see very often.

But, that aside, what initially attracted me to the work was the manner in which Jeff took something well-trodden – the coming-of-age story – and made it feel fresh and new again: his prose is so refined, so cautiously constructed, that it sears the page. While Mira Corpora is his first novel, Jeff is well-known as a playwright, where much of his work for the stage concerns the sensual experience of viewing art. It was jolting, in a very positive way, to see how he managed to introduce some of these sensual flourishes to prose.

It is a long process from acceptance of a manuscript to the point where it becomes known popularly, commercially, as a "book," which affords me the opportunity to get to know the author, oftentimes quite well. Following is an interview conducted over email, inspired by many of the conversations that Jeff and I have had, where we discuss the possibility of making reading hip again, the films of Terrance Malick and Harmony Korine, and the conservatism of popular authors.

Why is it okay for literature in translation to be tagged ‘experimental,’ but when the label is applied domestically, to books by U.S. authors, it’s a curse?

People don’t seem aware of the double standard. Often I think readers pick up literature in translation expecting it to be adventurous and experimental. There’s a long tradition of fiction from writers like Calvino, Borges, Murakami, Cortazar, and Kobo Abe where the formal experiments are part of the attraction. They’re a key ingredient in what makes their fiction so enjoyable. Maybe readers are willing to embrace this because translated titles seem like they’ve already been vetted: another publisher thought enough to translate them and they’re often accompanied by glowing reviews from around the globe. When these books get strange, the reader is willing to give them the benefit of the doubt. Or maybe it’s a case of believing that writers construct books differently outside the U.S. and therefore aren’t bound by the same rules. Because, certainly, describing a book by a U.S. author as experimental seems to be shorthand for "difficult," "pretentious," and "no fun." Most people suddenly feel like they’re being asked to eat their vegetables – and these vegetables also happen to be covered in shit.

Maybe there’s just something conservative at the bedrock of American fiction. It’s as if the great work of the 1960s by heroes like William Gass, Thomas Pynchon, William Gaddis, Donald Barthelme, etc. was an aberrant blip rather than a cavernous opening of new possibilities. Or maybe it’s just another symptom of the creeping conservatism that’s infected so many aspects of the culture. It’s sad because our country’s literary heritage springs from some of the most radical writing of the 19th Century: Emily Dickinson, Walt Whitman, and Herman Melville. You could throw Nathaniel Hawthorne and Henry James in there, too. Of course it also took a long time for some of those folks to get recognised for their achievements.

Dennis Cooper talks about how it was considered hip to read experimental literature in the early 1970s. If you liked cool music, you wanted to have equally good taste in movies and books. But I often find people who listen to interesting bands have no shame in reading and watching the absolute worst stuff. I couldn’t convince anyone in my independent film class to check out Spring Breakers, but several students saw the other James Franco movie that opened that weekend: The Wizard of Oz remake. Do you think it’s possible to make reading adventurous literature hip again on a mass scale?

I’m hopeful. I think a lot of the trouble was that we had a small pool of tastemakers in the print media who didn’t offer much diversity or range in what they covered, so literature and writers appeared very middle-of-the-road, very stiff, and were mainly only re-treading the same bourgeois topics. Franzen’s only interesting when people steal his glasses. In an interview with Creative Loafing, you had a great line about contemporary literature, where you said, "’ ‘Literary fiction’ is a great name for it, because it’s not actually literature — it’s fiction that has a literary patina. It’s this NPR-ification of literature."

The internet has fragmented society and made it easier to connect with niche audiences. Folks were bored seeing the same books reviewed redundantly, so many excellent web-based magazines sprouted up, and as their reputations blossomed, it became harder for traditional print media to ignore the books, authors, and presses they were covering. Now, it’s like Scott McClanahan said in an interview with The Rumpus: "The barbarians are at the gate." I believe we’re going to win.

Mira Corpora has been compared to punk music; in many ways you deconstruct and then re-construct new notions of what literature can do. You’re very well-versed in music and film. You founded the NoDa Film Festival in Charlotte, teach film, and run a popular jazz site, destination-out. Can you see any correlations between other mediums and the present state of literature?

The internet has obviously had a huge impact on all the arts. For music, it seems the ability to access so much rare music from far-flung eras and genres has been creatively harmful for many musicians. Everything feels a bit stagnant and flat right now. Maybe the amount of sonic options and the weight of history has become paralysing. I think that’s one of the reasons so many bands are recycling the past and playing out the phenomenon Simon Reynolds calls "Retromania." Sometimes this recycling is fascinating, but there’s also very little music these days that delivers the shock of the new.

For literature though, the ability to get and share information on the web about previously buried books has been a huge creative benefit. It’s provided writers with fresh inspirations and examples of different ways to shape stories and language. Great books by, say, Robert Walser and Anna Kavan now have a chance to be influential even though they’re not widely taught in MFA programs or prominently displayed in bookstores. There are parts of Goodreads where you can find people writing insightful reviews about authors like Raymond Queneau and creating excitement around wonderful books previously known only to specialists. Maybe this flood of information has been positive because books can’t be digested as quickly as songs. The slowness of literature is a natural defense against the internet’s tendency toward instant gratification. There’s less temptation to fill your hard drive with tons of novels that you’ll never read.

But even though exciting influences are seeping into the work of younger writers, there’s still the "literary fiction" problem you mentioned. So many people’s idea of good art seems to have become devalued. Maybe it’s easier to see this same thing in film. Take American Hustle, a movie that’s expertly hustled a lot of critics. It’s entertaining and well-made, but it’s an extremely conventional movie where the people you root for get rewarded and people you root against get a comeuppance. Yet it’s being touted as this amazing piece of art. Absurd. On the other end, a truly radical work like Terrence Malick’s To the Wonder is roundly dismissed as corny because it deals with spirituality and one of the actresses twirls in a field of wheat. The movie has its flaws, but it’s formally beyond anything being done in world cinema. Malick seems to be attempting nothing less than creating a new syntax with his editing, a new way of telling stories and moving viewers through time and space. His work is avant garde, but it’s also accessible. Thirty years from now people will marvel over it, but for now so-called Serious Critics are more interested in Christian Bale’s bad hairpiece. There’s a tendency today to experience art on autopilot, programmed with these received ideas that we rarely question. We’re not really seeing what we’re looking at.

I read the review that A.O. Scott wrote in the Times about To the Wonder, where he criticizes all the twirling in the film. One of Scott’s thoughts stuck with me in particular: he remarks that To the Wonder "look[ed] more commercial than cosmic, as if plucked from advertisements for perfume, high-thread-count sheets or other luxury goods."

As someone who I feel has done this successfully with Mira Corpora, how can artists subvert this ‘seen-it-in-a-commercial’ vibe to their work?

It’s insidious the way the media colonises our imaginations – often without us even realising it. Some film critics talk about the importance of "resisting images" that can’t be easily repurposed by mass media. I think it’s smart to avoid images that are too familiar. I like tweaking scenes so they’re slightly surreal and don’t instantly fit into a fixed mode – either realism or fantasy. I also try to short-circuit pre-existing associations whenever possible. I don’t want anything to feel lazily cut-and-pasted from somewhere else. For Mira Corpora, I also worked to particularise the images so they felt like they could only thrive within the context of the book. As soon as you put a group of kids in the woods, everybody thinks, ‘oh right, it’s like Lord of the Flies!’ I went out of my way to ensure the woods section of Mira has its own feel and imagery. Instead of rampant chaos, there are moments of tenderness and sacrifice.

This problem happens with more than just images – it also occurs with story arcs and prose style. There’s a danger of internalising marketing ideals about how a story should be told and what constitutes a satisfying narrative. Too often prose styles are either simplified so readers can easily follow every moment or authors craft sentences that are self-conscious trying to signify that they’re "literary." Both are ways of catering to the marketplace.

I felt that way about Rachel Kushner’s The Flamethrowers. I could certainly see that book being the literary equivalent of American Hustle in 2013. I was excited to read it – it was all over critic’s best-of-the-year lists, and many readers whose opinions I genuinely value thought it was pretty righteous. Once I finally got around to reading it, I was disappointed. Fiction is subjective, sure, and I feel as though my disappointment could be a result of my own bloated expectations. I found The Flamethrowers to be mostly unexceptional, conservative, and – as you say about prose styles in your previous response – simplified. I know based on our past conversations that you had something of a similar reaction

I was excited to read it, too. And like you, I was underwhelmed. The opening chapter with the speed trial at the Salt Flats was impressive, but the book lacks propulsion after that. While there were some interesting elisions and descriptive flourishes, it felt closer to generic literary fiction than I was expecting. I’m interested in all the topics in The Flamethrowers: New York City in the early 1970s, conceptual art, violent communes, Barbara Loden’s movie Wanda, the Red Brigades. Unfortunately, the book’s style and structure isn’t nearly as adventurous as its subject matter. These disruptive topics are handled in a largely conservative way – and they’re tamed by the novel’s traditional approach.

In a Bomb interview, Kushner says "The art world is all change and reflexivity and the dematerialization of forms, while the novel is stiff, fairly unchanging, and conservative as a form." I could be wrong, but it doesn’t seem as if she’s lamenting this. To me, this is the crux of the problem with contemporary fiction. Writers often accept these received ideas of what a novel should be, when we need to push for new forms and fresh narratives and make the experience of reading fiction feel, you know, novel. I’ve always liked the Guy Debord quote, "The passions have been sufficiently interpreted; the point now is to discover new ones."

But maybe high expectations thwarted me as well. It’s strange because I feel like we’re the only two people out there who were underwhelmed by this book.

I think that social media dictates that we live in a polite age, where everyone enthusiastically reads one another’s books publicly on twitter. Writers seem very tepid, and not at all hardy. It doesn’t feel like a conversation. Scott Bradfield wrote a great essay for The Denver Quarterly about why he doesn’t like Toni Morrison’s Beloved – which is largely because it’s not okay for a reader to have their own opinion or any kind of original reaction to the book; you’re supposed to automatically accept it as classic literature. Why is it so tough for us to state publicly that we don’t care for a celebrated contemporary book like The Flamethrowers?

It seems that internet culture makes it difficult to maintain proper respect while asking tough questions as part of a genuine conversation. Maybe that’s because it’s hard to control how people hear the tone of your words in print. The web also seems better suited to clever quips than substantive dialogue. It’s too easy to seem like you’re callously – and jealously – shitting on someone’s hard work, rather than trying to explore your reactions to their aesthetic choices. Writing is a tough racket and I totally understand the desire to accentuate community and mutual support.

For me, it’s particularly tough to talk about The Flamethrowers because it’s clear from her essays and interviews that Rachel Kusher is stunningly knowledgeable about visual art, film, and literature. Her recent ‘By the Book’ piece in the New York Times is the best they’ve run: she talks about Alejo Carpentier’s fiction, unusual recent novels like Morvern Callar and Ingrid Caven, the artist Martin Kippinberger. I often find myself taking notes whenever she discusses art. I’d be curious to talk to her about the decisions behind The Flamethrowers. I’m surprised that someone who champions writers like Celine isn’t more adventurous in her own work.

I find myself taking notes whenever we talk, and coming away with excellent and unexpected books and films to check out. You’ve discussed Malick and Harmony Korine, but what are some other contemporary works that you’d recommend not be overlooked?

I haven’t been reading quite as much lately since I’m deep into a new novel, but I made sure to check out Dennis Cooper’s The Weaklings. It’s a stunning new collection of verse and prose poems, structured so the images and themes generate a series of dizzying echoes. Ken Baumann’s Say, Cut, Map is remarkable for how it shifts from sentence-to-sentence, but still propels the reader through an emotional matrix of family, sex, and sickness. I’ve been knocked out by Joyelle McSweeney’s use of language in Salamandrine: 8 Gothics, how the words slip, skid, pop, and burrow through the stories, creating a daisy chain of indelible effects. M. Kitchell’s Memoir: Death Spasm of the Sun is probably the closest thing I’ve read to J.G. Ballard’s work – a visionary amoral tale of the hyper-wealthy in an alternate future. Houston Rap is a combo photography book and oral history that was nine years in the making. I’m sure its intimate stories and images will haunt me for a long time to come. Ben Katchor’s latest collection of comic strips, Hand-Drying in America, is typically brilliant. With sections on "Hair Travel," "The Price of Tassels," and "The Pill Shearer," its fantastical sociology should appeal to anyone who likes Italo Calvino.

For movies, Criterion released Roberto Rossellini’s films with Ingrid Bergman for the first time on DVD. All those movies are worthwhile, but Stromboli in particular is a must-see. Rosselini is considered the founder of Neo-realism, but this is close to straight-up surrealism. There’s a desolate stone village, black sands, a brutal fish kill, an attempted priest seduction, and a prolonged sequence of Ingrid Bergman writhing on the side of an actual smoldering volcano. Upstream Color was my favorite new release last year: a puzzle movie about desperate love, stolen identity, and fetal pigs that’s also visually and sonically ravishing. I love everything by Jem Cohen, who’s best known for his documentaries about Fugazi and The Ex. I was glad that last year’s Museum Hours was a minor art-house hit. It combines a tender relationship story, a travel film about Vienna, and art history into a stirring and unique construction. I hope more of his work becomes commercially available, especially his highway strip-mall reverie Chain.

And if you’re anywhere near the Mike Kelley art retrospective that’s touring the country, that’s worth a serious drive. He worked in an astounding variety of genres and his stuff manages to be simultaneously trashy, melancholic, and sublime. It’s immediately gripping and deeply mysterious. The best combo.

Mira Corpora is out now, published by Two Dollar Radio