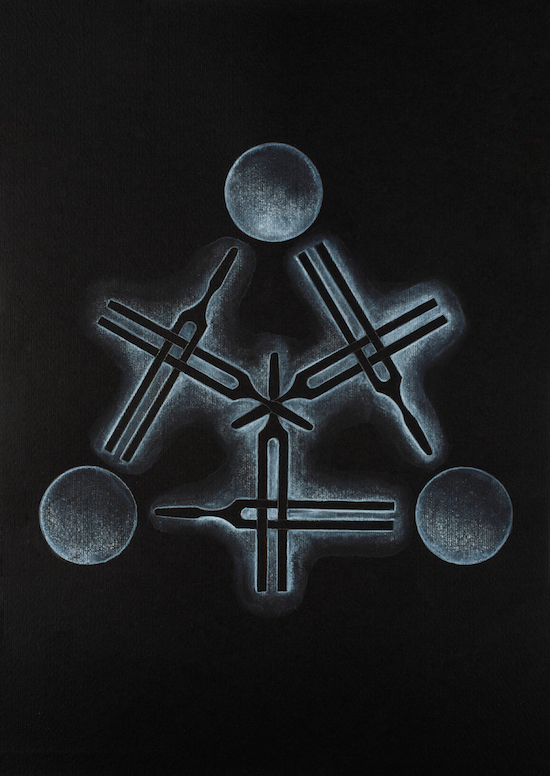

Aura Satz, Tuning Fork Spell 27, ongoing 2020-22 (photo Pete Moss)

On the Zoom screen before me, Laurie Anderson is testing her microphone. I’ve accidentally signed in fifteen minutes early to the online launch of Quantum Listening, a new edition of Pauline Oliveros’ 1999 manifesto from Ignota Books. An alert signals that Annea Lockwood – the avant-garde composer famed for her Fluxus-inspired burning and drowning pianos – has arrived.

“Hi, Annea!” Laurie drawls. The pair share familiar words of greeting as more and more people turn up – Stuart Dempster logs on and nods a hello, followed by Morton Subotnick and Ramon Sender. It’s as if I’ve wandered backstage, into a virtual green room where a cast of some of the most iconic avant-garde composers of the last century are hanging out and catching up.

It would have been Oliveros’ 90th birthday. To mark the occasion, her friends, collaborators, students of the San Francisco Tape Music Center and Center for Contemporary Music, and her partner in life as well as art, IONE, have joined together for a series of digital talks, performances and a sonic meditation.

The atmosphere of the evening encapsulates the tender tone of the slim, seventy-two-page publication, which opens with Anderson’s words: “Whenever I think of Pauline I think of laughing.” A purple dustjacket enfolds the volume – the visual identity of Ignota’s Terra Ignota series, which launched in 2019 with a reprint of Ursula K. Le Guin’s seminal 1986 essay, The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction. In cartography, the phrase terra ignota or terra incognita refers to unknown, unexplored areas of land or sea. These uncharted expanses would often be marked by the apocryphal line, “Here Be Dragons”. With these reissued texts, the publishing house strives to unveil illuminary writing – perspectives which cast light on new ways of understanding art and technology.

Draped in pastel fabrics, strings of beads and a large pair of tinted sunglasses, IONE launches into one of the playful exercises outlined in Quantum Listening. “Think of a sound you loved to make as a child,” she guides. “There was likely a moment in your childhood when it was really fun to make sounds – especially ones that adults admonished you for making. Let’s begin with a nice deep breath – and exhale the air audibly. On the next inhale prepare, then make your first sound on the exhale. Continue by listening for a space for your sounds before, after, or with someone else’s sound…” The video erupts in a cacophony of noise: wails, screams, shouts, stammers and giggling.

Grounded in these simple yet profound exercises, Oliveros set out to develop deep listening. She defines this practice as a lifelong endeavour, one that spanned her fifty-year-long career and compositional oeuvre, which includes a vast repertoire of electronic works and improvisations designed to deepen everyday engagement with sound. Its namesake stems from 1988 when, together with Stuart Dempster and Panaiotis, she descended into the Dan Harpole Cistern, a long empty receptacle for water fourteen feet underground, built by the US Military near Seattle, Washington. In the depths, they listened intently as their sounds reverberated back to them with an extraordinary delay of forty-five seconds. Later on, the group returned with recording equipment, resulting in the 1989 album Deep Listening – its title a pun on the subterranean location.

Albeit ever-morphing into new forms according to shifting political, pedogogical and sonorous contexts, as laid out in the book, deep listening can be understood as “listening in every possible way, to everything it’s possible to hear, no matter what you are doing.” So much, after all, is lost to the white noise of existence. But by tuning in, sensing one another and the world differently, we can embody a heightened state of awareness. “It is through such listening,” writes IONE in her introduction. “That transformation is possible.”

For this edition, the editorial team at Ignota have honed into the context of the invasion of Ukraine, drawing parallels between the anti-Vietnam war movements of the 1960s and the present-day conflict. Oliveros’ sonic mediations were in part a response to the self-immolation of George Winne Jr., who set himself alight in 1970 at the University of California, San Diego, where she taught. Following this traumatic incident and deeply affected by the ongoing violence of the war, she set out to utilise communal, immersive encounters with sound as conduits for a radically transformed social matrix: one in which compassion and peace form the basis for our actions.

Deep listening can also be a profoundly psychoactive experience. Becoming attentively submerged in sound can cause auditory hallucinations – spectral utterances emerging entirely from the imagination. In Quantum Listening, this facet is touched upon with IONE’s observation that scientific experiments have shown that the tympanic membrane of the ear, commonly known as the eardrum, responds to sounds in our dreams as if such noises were real.

In relation to nature, the practice cultivates an awareness of landscapes and non-human creatures as active, sentient and resonating beings, rather than as passive resources for plunder. We are urged to engage with hearing from a non-anthropocentric perspective: “What if you could hear like a bat zipping and swooping around the night sky, or a whale sounding the depths of the oceans, or elephants sounding the earth?”

Combining the mystical, the ecological, and the technological, as well as the capacity of our own bodies to hear, sing and harmonise, deep listening emerges as both a social and auditory practice – one which holds the potential to radically re-orientate our relationship with the world around us.

But precisely what the “quantum” refers to is somewhat opaque. Notoriously difficult to grasp, in physics, quantum theory describes the behaviour of matter and energy on atomic and subatomic levels. My own, limited understanding is rooted in the work of theoretical physicist and feminist thinker, Karen Barad who elaborates on agential realism in her book Meeting the Universe Halfway (2007). Like Barad, Oliveros thinks with entanglement – the irrevocable ties between all matter, actions and encounters – as well as what scientists call “the field” – or the physical manifestations of forces. She articulates how sounds are impacted by each other, how they merge, echo and combine, and how listeners both simultaneously affect and are affected. For instance, in the case of the Dan Harpole Cistern, noise emanates from the instruments of the musicians, reverberates off the concrete walls and bounces back against the human bodies standing in the space, rippling out and interacting with every surface they touch. In this way, sound has no focal point and we are encouraged to tune into every fluctuation accordingly.

Over the decades, Oliveros’ resonance has waxed and waned. Certainly, in niche circles, she is known as a tour-du-force; an exceptionally talented, classically trained composer who took a visionary, philosophical approach to sound. Yet in dominant narratives surrounding the emergence of electronic music, her contribution – alongside the role of women more generally – has remained relatively obscure. In recent years, this has begun to change. Notable retellings include the 2020 documentary Sisters with Transistors (2020), a feature-length documentary focusing on electronica’s female pioneers, featuring the likes of Delia Derbyshire, Laurie Spiegel, Suzanne Ciani and Oliveros herself. Or the forthcoming publication by Cosey Fanni Tutti, Re-sisters (2002) is a hagiography that sets out to draw links between Tutti and Derbyshire, as well as the life of Margery Kempe, the 15th-century mystic visionary.

Although, as Quantum Listening makes clear, the category “female musician” as a genre or uniform category is not without limitation. In the book, Oliveros emerges as an idiosyncratic character who braided together many different realms as influences. Her methodology was borne as much from rejections of masculinist “control” or “mastery” over instruments, as her devotion to Buddhist teachings and Tai chi. It is at least partially the openness of her doctrine – her malleability and receptiveness, which marked her relationship with other composers and her students – which is responsible for deep listening becoming so rich as a concept.

In one of my favourite anecdotes in the book, IONE recounts the final performance of Oliveros’ Tuning Meditation. Intended for healing, the meditation can be enacted anywhere and involve two people or thousands. The assembled group is encouraged to sing a single note and then find one another in a harmony. The resulting piece is unique each time it is presented, completely dependent on its participants and environment. Taking place in London at St John’s Church in Smith Square, Westminster, the very last mass transmission of Tuning Meditation occurred just after the Brexit vote in June 2016. Oliveros directed the score from the stage for over 500 singers, whose voices rose and fell, filling the cathedral to the high, vaulted ceiling, then ending breathtakingly, entirely in unison. I was able to locate only one recording, made by an audience member who had a phone hidden inside their pocket. It’s in extremely low quality, but even so, it’s worth a listen – the magic atmosphere of togetherness that Oliveros was able to conjure is palpable. It’s here, in the voices of this intuitively led choir, where the practice of deep listening is at its most captivating.

Pauline Oliveros, Quantum Listening, is published by Ignota Books