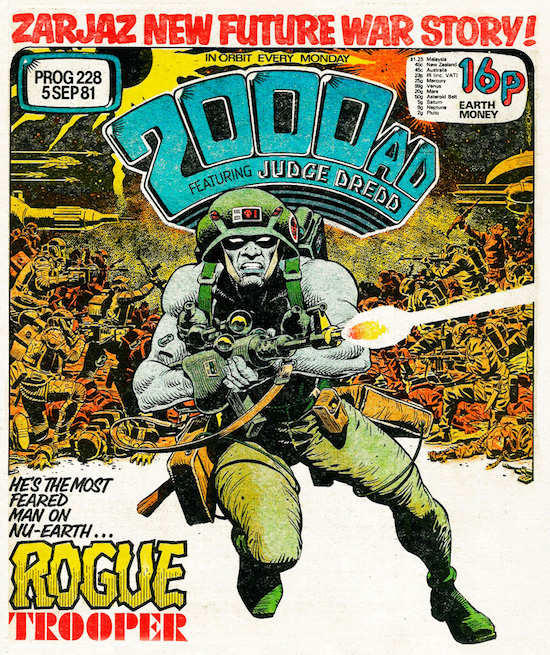

Judge Dredd® Judge Dredd Is A Registered Trademark, © Rebellion A/S, All Rights Reserved

In 1982 or thereabouts, when I was around 11 years old, I got hold of a copy of 2000AD – I don’t know how, an older kid than me must have had one. I still remember the feeling of raw fear that filled me when I opened the page to see a character called Nemesis The Warlock. An eyeball-searing hybrid of Satan, a goat, a gazelle and a pterodactyl, Nemesis was engaged in a war with a cyborg parody of a Catholic bishop called Tomas de Torquemada, named after the real-life 15th-century Grand Inquisitor. In a deeply disturbing version of hell, Nemesis and Torquemada were battling it out with spears and magic, while all around them people were being burned alive.

It was truly horrible, and I wasn’t even from a religious family. I can’t imagine what the impact of Nemesis would have been on a Catholic kid. Through the fear, I thought it was amazing.

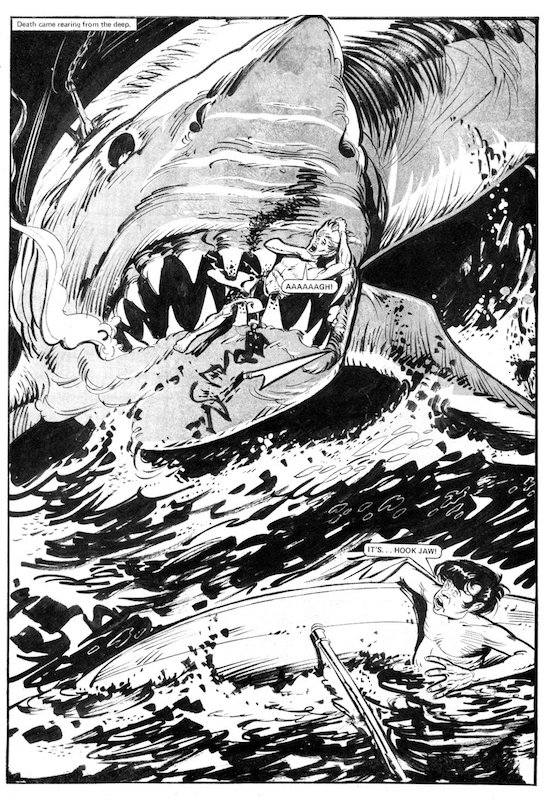

Around the same time, some kid at school showed me a copy of Action magazine. The most popular strip in the comic, which had been banned a few years before for its graphic cover, was about a great white shark called Hook Jaw who chewed people to pieces, in full colour. Again, I nearly pooped my pants. It felt great.

The next time I read 2000AD, I saw Judge Dredd for the first time – and that was it: I was addicted for life. Not because Dredd is a nice guy or anything. He’s essentially a total bastard of a policeman who hands out death sentences to criminals all day, every day, while patrolling the streets of an unpleasant future metropolis called Mega-City One, set on the east coast of the USA. Dredd is part Dirty Harry, part psychopath, and at the same time a confusing but somehow appealing blend of left- and right-wing values. You wouldn’t want to meet him.

But you’d definitely like to meet the people who dreamed him up. As writer, editor and 2000AD founder Pat Mills explains in his new autobiography Be Pure. Be Vigilant. Behave! (the rallying cry of his Torquemada creation), Dredd was invented between three people in 1977, when Mills was asked to create the 2000AD comic. Mills came up with Dredd’s name, riffing on the reggae band Judge Dread, and wrote many of the strip’s early stories; meanwhile, the character’s writer-creator was John Wagner and the artist-creator Carlos Ezquerra. It’s a complex situation but one which Mills clarifies in his book, fortunately.

Mills also came up with Nemesis The Warlock, and – surprise, surprise – had also previously been responsible for Hook Jaw and Action, making him the guy responsible for scaring me half to death as a kid. However, in Be Pure he has rather more important points to make than merely being the man who caused a generation of comics fans to collectively crap its pants.

Nemesis™ Rebellion A/S, © Rebellion A/S, All Rights Reserved

The big stuff which Mills reveals is as follows; some of it will be depressingly familiar. One, the British comics industry is in deep trouble. As with the rest of the print environment, digital distribution has eroded profits, while a broader range of entertainment options for the public has reduced revenue. Two, creators – by which Mills means artists, editors, letterers, developers and the like – are underpaid and overstretched, with pressure to produce at scale leading to miserable working lives.

Three, and the worst part of this is that it’s a largely British phenomenon, our comics industry is stingy with its intellectual property rights, meaning that creators are often deprived of legal ownership of their work and therefore a traditional career income from royalties and reuse fees. When you consider that a large, and lucrative, sector of the comics industry is devoted to luxurious collections of previously-published stories (does this sound familiar, musicians?) it’s even worse.

Along the way, Mills provides example after example of the appalling behaviour of those in charge, largely publishers and editors. Although he clearly isn’t referring to all publishers or all editors, those most responsible for insulting, harassing, demeaning and excluding their creators tend to fall into those categories.

A few anecdotes come to mind – one where priceless original artwork is used to block a leaky pipe; another where a budding 25-year-old writer is told that no matter how good he is, he won’t be an editor until he’s 30; one where a fictional invasion by a Russian army has to be attributed to the ‘Volgs’ for fear of causing ructions; and yet another where a black character is replaced with a white one with no explanation.

It’s grim stuff, although leavened at every step by the funny, crazy stuff which Mills has seen and done over the decades. He explains that Dredd and Torquemada were both partly inspired by a priest at the Catholic school which he attended as a kid. Said cleric was so moved to apply corporal punishment that he would literally run across the classroom to his victim, cane held above his head.

Mills’ views on a variety of relevant subjects are educational. He roundly despises the usual American superheroes, or ‘men in tights’ as he calls them, for their straight-laced, conservative politics. His own Marshal Law, a satirical character first published in 1987, is the antithesis of the DC/Marvel canon. He also explains how the thinking behind girls’ comics – which were massive sellers in the Seventies – influenced boys’ equivalents, making it clear that masculine as Dredd and the rest of the 2000AD heroes are, they’re not mere testosterone.

Surprisingly, Mills is tolerant towards the first Judge Dredd film from 1995, a routinely hated adaptation ruined by its lumbering comedic nature and the casting of Sylvester Stallone as Dredd. As he accurately points out, getting a Dredd film made at all – given that the character is barely known in America – was a hell of an achievement.

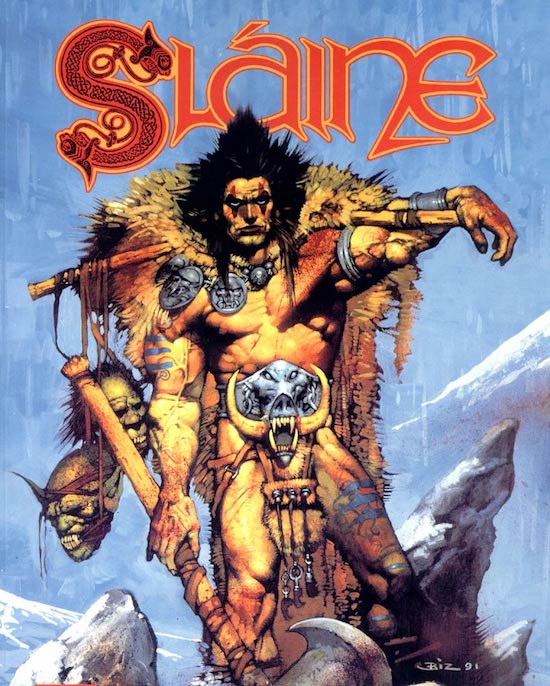

Above all, Mills exults in his recollections of the heyday of 2000AD, before readers moved on, the industry began to collapse, the publishers panicked and one or two unwise editors tried to turn it into Loaded (or worse). The happy ending, where the comic is picked up and managed properly by its current owners Rebellion, continues today, although Mills laments the clinical way in which he is treated compared to the old days. Back then he, his artists and writers would collaborate in a kind of drunken comradeship, knocking out all-time classic series such as ABC Warriors, Slaine, Strontium Dog, Flesh, Ro-Busters, Nemesis, Rogue Trooper and the rest of the great 2000AD canon.

These were truly team efforts, Mills explains, taking great care to assign credit where it’s due and to explain the contribution of each creative. Any comic editor would be lucky these days to employ talents as fierce as those of Kevin O’Neill, Alan Moore, Grant Morrison and John Wagner. Even on the Dredd strip alone, the differing styles of Carlos Ezquerra, Brian Bolland, Mike McMahon and the late John Hicklenton gained them huge numbers of devotees.

This golden age is long gone, but Mills – now 68 and travelling the world – isn’t sitting back and relaxing just yet, with his own publishing venture up and running at millsverse.com. Always something of a firebrand, he featured memorably in 2014’s Future Shocks documentary, signing off with a seething ‘You don’t know what the fuck you’re doing with 2000AD, so leave it the fuck alone!’

Pat, can I start by saying that the most frightening moments I experienced as a kid were thanks to you? When I read Nemesis The Warlock and Hook Jaw, I was terrified.

Pat Mills: Ha ha! That’s great to know. Things like Hook Jaw and Flesh are about cathartic fear. I think there are such things as wholesome fear and unwholesome fear, although I don’t know if anyone has ever defined them properly or done any work in that area. The aim was to really excite people. When I was growing up and reading endless amounts of pulp fiction, it was always the books that scared the living daylights out of me that I went back to over and over again. It was a more entrancing world than the council house I grew up in.

Has Be Pure been a long time in the making?

PM: Yes and no. I did a blog which covered some of the items in the book, and then expanded from there. What really prompted the book was that it’s 2000AD‘s 40th birthday this year, and I thought ‘If I don’t write about it now, when will I?’ All of us have kept very quiet about some of the things in British comics which are incredibly awful – and it really is time to say something about them.

I thought you had balls saying what you did, especially as you’re still working for some of those people.

PM: Yeah, ha ha! I thought that too. If I wasn’t working for them, I’d probably have been harsher still, so there’s a certain restraint there. But these things should be about transparency and honesty. If you’re just a robot, working for a machine, that’s no fun. Eventually you have to say something.

You talk at length in Be Pure about the shoddy treatment of creators by publishers, especially when it comes to intellectual property rights.

PM: That’s probably the most important point in the book. I hesitated about how far to go into it, because I thought it might be a bit boring for the general reader, so I didn’t get too carried away – I hope! But I had to say those things, because the lack of rights is what has destroyed the British comic industry. The only thing that keeps us going is a love for the comics. We’re hanging by a thread.

You compare the British industry to the more robust French equivalent, where creators are paid appropriately for their work.

PM: Absolutely. Japan, France and the USA are the leading countries for the comic industry, in that order. I said that to an American journalist and he said ‘Are you sure?’, but it’s correct because I’ve seen the sales figures. In the case of France, the Asterix series is obviously exceptional: orders of those comics can be around five million. Even the biggest American comic book will do 100,000 at the most.

How do British comic sales stand up?

PM: Not very well, certainly when you compare them to their heyday, when Tammy was selling over 200,000 copies a week, and over a quarter of a million a week when it merged with Sandy. 2000AD sold 200,000 copies a week as well, and it maintained those figures for quite a few years. They went down, of course, but significantly, they went up again with The Horned God [in 1989-90]. What does that say? It says that when you find a superstar like [artist] Simon Bisley, and you get fully painted artwork, people go out and buy the comic who normally wouldn’t do so. In recent days, the circulation of comics like 2000AD is way, way low. It’s a guarded secret, but I think it’s south of 20,000.

Is that connected to the all-round slump in the publishing industry in the digital age?

PM: Those factors do come into it. Comics professionals will say ‘Well, we lost our readership because the print industry is changing, and kids play computer games instead’ and so on. The very clear answer is that they have computer games in France as well. Critics will say ‘Ah, but the French are different. Their culture is different and you can’t draw parallels’. Well, you can, because of [fantasy games manufacturer] Games Workshop, which started at the same time as 2000AD and is one of the most amazing success stories of all time. I would have thought that selling comics to kids would be easier than selling them tabletop games, too.

Strontium Dog™ Rebellion A/S, © Rebellion A/S, All Rights Reserved

The Nineties were rough for 2000AD. Why was that, do you think?

PM: There was a strange period in that decade when some of the established names on the magazine were being publicly pilloried by the editor. A classic example was [artist] John Hicklenton. Here was a guy who was suffering from multiple sclerosis and was getting publicly trashed in quite unpleasant ways. For most of the Nineties I was busy writing and having a life, and thinking ‘Just ignore it! Who cares?’ but by the end of the decade I thought ‘Shit, I’ve got to do something’.

John was a force of nature, wasn’t he?

PM: He was. The sad thing is that a lot of cult artists like him will never have the same success as mainstream artists. Take Brian Bolland, who is both a wonderful cult artist and a mainstream artist, so everyone loves his work. An artist like John Hicklenton will tend to have a cult following: it will be very strong, but it will be a minority. Those are the guys that have been squeezed out of 2000AD.

So the magazine has suffered?

PM: Yes. In recent years I’ve been in absolute despair, because there was a time when I could introduce an artist to an editor, who would say ‘Okay, let’s go for it’. On balance, I think my choices were more right than wrong. Occasionally there would be one who wouldn’t fly at the box office, so to speak, but even then there was a good case for them. A great example is the one I mention in the book, Fay Dalton, who is now very successful elsewhere. If you look at her work, you think ‘Wow!’ But can I get her into 2000AD? No. I ask myself why. It’s not like her work is obscure or too cult-orientated: it’s slightly chocolate-box, and it’s very sexy. The only conclusion I can come to is that she doesn’t fit some kind of narrow perspective of how things should be. I hope and pray that isn’t what’s happened to 2000AD, but there are some indications of that kind of conservative thing that goes on with a lot of successful characters in media. You get publishers saying ‘This character has to have six buttons and you’ve only drawn five!’ and all that kind of stuff, with a very defined look for the characters – although one of 2000AD‘s successes was that it’s quite random and quite wild. One Slaine could look very different to another in the early days, for example.

So what’s the solution?

PM: The problem is that when you have relatively low sales, and you’re under a lot of pressure, the inevitable thing that editors do is play is safe. But if you play it safe, especially on a comic like 2000AD, you’re going to get readers complaining and saying ‘It’s not as edgy as it used to be. Where’s the spark?’ You need that edge, not just for the existing middle-aged readership, but if you want to attract kids. Maybe not as edgy as John Hicklenton was: I’m not sure his work would go down well with a 13-year-old, who might look at it and say ‘I don’t understand this’. But you need to be edgy on some level. Look at the computer games that kids play – Assassin’s Creed, and Halo, and Grand Theft Auto and so on: they’re all pretty sharp.

Is your voice being heard, do you think?

PM: No. The argument I raise is one that people really don’t want to hear. I know it’s a genuine argument because I, as much as anyone else, am responsible for losing those kids. We all collectively have to take some responsibility for the fact that we lost those young readers, the 11, 12 and 13 year olds.

Slaine™ Rebellion A/S, © Rebellion A/S, All Rights Reserved

You mentioned the C word, conservatism. It’s a prevalent theme of Be Pure, starting with the violent priests at your school who inspired Dredd and Torquemada, through to the old-school publishers in 2000AD‘s early days. Surely the comics industry is less conservative these days?

PM: Not conservative, perhaps, but emotionally detached. I don’t even get a Christmas card from Rebellion. I’m not just paranoid, it’s the same for all of us! When you’re short of time, something has to go out of the window, and perhaps it’s the emotional connection with staff. It does seem to be a sign of the times. It’s so different to the pre-computer era that I grew up in. It was very normal back then for everyone to spend long, drunken lunchtimes – not just in comics, but the whole of Fleet Street – and to come up with great ideas out of that admittedly pretty awful way of doing things.

Be Pure explains in detail the difference between a creator and a developer, and also points out that being the latter might entail a period of six weeks developing a series, without being paid for that time.

PM: It’s a bad one, isn’t it? And it’s been largely unknown before now that a long period of creative development is required. Six weeks is the minimum time for a great character, someone like Judge Dredd, Strontium Dog or the ABC Warriors. If you think how long it takes to write a novel, six weeks is cheap at the price. Again, it’s all a part of the contraction of the British comic market. In the past, publishers knew that you needed that development period, and they would try different ways to help you do it.

What is it like to be a comic creator in 2017?

PM: It’s all a little bit wretched. All the creators on 2000AD are faced with the problem of getting it done very quickly. British creators are no less talented than the French or anywhere else: they don’t want to cut corners, but eventually they have to. If you’re an artist who is supporting a family, you’ll have to work incredibly long hours, as I know from a couple who I’ve spoken to recently. You’re talking about eight in the morning until 10 at night, which you can get away with when you’re 25, but once you get to 50 or whatever, it’s not a particularly healthy thing to do, and you also want to have a life.

Are you the only person pointing out that there’s a problem?

PM Pretty much. People really keep their heads down, but for some reason, I don’t! Ha ha! I just had to say ‘Fuck it’ and put my head above the parapet – and as I started the comic, I guess it’s appropriate that it should be me. There’s a certain pleasure in being subversive.

Your work has been reprinted in collected form many times. Is it a mixed emotion when you see a new Pat Mills book, because it’s such a beautiful artefact but the royalties you get are so crap, or even non-existent?

PM: That’s a very good way of summing it up – it’s a mixed emotion. You think ‘How much am I going to make out of this new edition?’ and it’s a hundred quid. Now, those aren’t royalties as freelance authors know them. Because I’ve got so many books out there, collectively they’ll add up to something, but it’s still a mixed feeling and I don’t really know how to cope with it. With a book of your own, with a proper rights deal, you get a sense of satisfaction that is missing with a collection for which you get almost nothing, even though it’s absolutely beautiful, as some of these Rebellion books are. These deluxe ABC Warriors books are on high-gloss quality paper and beautifully put together. So yes, it does pull me both ways.

Hook Jaw™ Rebellion Publishing Ltd, Copyright © Rebellion Publishing Ltd, All Rights Reserved

Perhaps this spurs you on to take care of business more diligently with your own books?

PM: Yes. To be honest, I would have been quite happy writing for comics until retirement, but as the money shrank and shrank I realised that I couldn’t do it. I would have ended up working seven days a week, which I’ve done from time to time, and it’s madness.

You’re now building a publishing business.

PM: A couple of years ago my wife Lisa and I started digitally publishing my French series, Requiem Vampire Knight, in English. We then started publishing properly in January this year, with Serial Killer, a comedy thriller co-written with Kevin O’Neill which is a twisted, alternative history of British comics. I followed that with Be Pure, and I’m currently finishing the sequel to Serial Killer, which is Goodnight, John Boy. We also have another two or three projects which are being launched shortly. The speed with which we can originate and then publish is refreshing, because we’re not dependent on artists creating the artwork, or publishers fitting us into their schedule. We’ve found that sales are sufficiently high to be a viable business: Be Pure in particular has sold exceptionally well. The sales easily surpass any money I would make writing a comic story in the same amount of time. That’s a really nice feeling.

So is the comics industry in this country likely to keep going downhill?

PM: My experience of moving away from the industry is going to be mirrored by others, who will also move away. Doubtless people will come forward to take our place, but the net result is a dilution. The editors of the past thought ‘When these guys go off to America or France, fuck ’em – we’ll get new guys to take their place’. And for a while, that was true, if you think about guys like Glenn Fabry and Simon Bisley and Jock coming along, but in the last decade, as far as I’m aware, that’s no longer the case. The majority, and perhaps all, of the new kids on the block will go straight into computer games or American comics, and occasionally to France, as I did.

Is there any good news?

PM: The wonderful thing is that 2000AD is no longer under threat, as it was in the Nineties. I don’t study it in sufficient detail to comment, because I made a promise when I left my editorship that I wouldn’t do that, and I’ve stuck to that promise. However, at the heart of the comic is a counterculture. The stories should always be countercultural. My way of doing that is very different to Grant Morrison and Alan Moore and John Wagner, but the common thread running through all four of us – and other writers – is a sense of challenging some aspect of the status quo, taking the piss out of it and criticising it. If the stories ever became ‘regular’ science fiction, if there is such a thing, that would be a dilution. The reader is looking for a collective, challenging experience through all those stories, and if in one story they don’t get that, my God the readers will hang them out to dry.

For better or worse, isn’t the world less about protest these days? A lot of people accuse anyone under 30 of being totally uninterested in challenging the status quo, because they’re too busy looking at their phone in Starbucks.

PM: It’s possible. In the Seventies, when I was writing countercultural stories, there was nothing remarkable about them. Charley’s War was anti-World War I: so what? It didn’t really stand out from the herd. That went on right through the Thatcher era. When Crisis – the 2000AD spinoff – appeared, that wasn’t some minor aberration by the editor: it was a reflection of the fact that teenagers buying 2000AD were pretty bolshy.

When did things change?

PM: In the early Nineties, when there was a backlash against these political stories. Readers were saying that they wanted Slaine to be slaying dragons in Simon Bisley’s pictures, rather than discussing mythology. This is a guess on my part, but as the decade progressed, and sales went down, I imagine that the editors said, ‘Why are we losing sales? We must be too political. Let’s get Pat off his soapbox!’ I was definitely told to tone down my act, which I did a bit, because I needed to eat, and retreated into science fiction. I created a character called Finn, a green activist with an occult side and lots of action, although he’s never been collected in book form. But yes, society has become very dumbed down, and it’s probably going to take some awful political event for that to change, the equivalent of the poll tax riots.

Talking of occult matters, in the book you mention your experiences of seeing UFOs.

PM: I would have loved to write more about those things, but I didn’t want anyone to throw the book away in disgust! I was on a late-night programme about UFOs once, and another guy was on there who thought the show was taking the piss out of him, and he trashed the studio and had to be removed by security… I was fascinated by other people’s reactions when I told them I’d had a close encounter of the third kind. My twin daughters were in their mid-teens at the time. One of them said ‘Can I come along and see them next time, Dad?’ and the other one said ‘Have the police been called?’ Ha ha! Everyone reacts to these phenomena differently. A lot of people who have had UFO experiences rarely talk about them, because they don’t want to be taken away by men in white coats – although of course it’s all right for a comic writer like me, because we must be nuts anyway!

What did you think of the 1995 and 2012 Dredd films?

PM: It’s become so standard to rip the first one to shreds that my natural instinct is to defend it, but I’m not going to put my head on the block and go that far! I think the robot was great in it, and some of the special effects were good, but what puzzles me is that it was quite leaden in places. Most science fiction films do well at the box office even when they’re not very good, but the 1995 Judge Dredd was really castigated. I’m looking for some new insight into it, rather than just saying ‘It was awful because Dredd kissed Judge Anderson’ or ‘He shouldn’t have taken his helmet off’. I think the real problem is that the character wasn’t known in America at the time, and barely is today. Perhaps there aren’t the necessary cultural links for Dredd to do well in America, and I think this applies to the 2012 Dredd film as well, which I preferred, of course. The sad thing is that Dredd originated from the American underground, from a script called Manning that John Wagner and I loved.

If Rebellion and 2000AD‘s current editor Matt Smith said ‘Pat, we’d like you to be the editor again’ and offered you the right package, would you say yes?

PM: Oh yes. I’d have to, wouldn’t I? It’s not going to happen, but I would be tempted, because the emotional bonds that link us all to books and magazines and comics which we’ve been involved in never go away. You’re still tied to them.