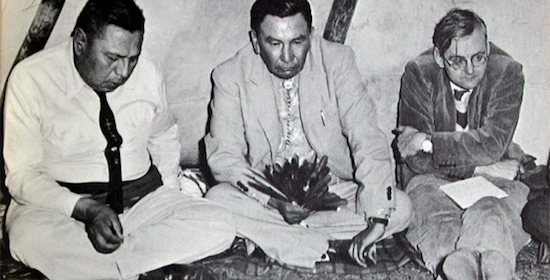

Humphry Osmond at a peyote ceremony

When I saw drugs expert David Nutt give a lecture a few years back – the man famously sacked by the government for saying that horse riding was more dangerous than taking ecstasy – he described the effective ban on utilising psychedelic drugs in mental health research from the 1960s to present as one of the greatest and most damaging scientific suppressions in history.

P.W. Barber’s new book traces a specific thread of this story, focusing on three scientists in the Canadian province of Saskatchewan, the work they did in using LSD as a treatment for schizophrenia and alcoholism, and the repercussions of their research over the following decades. The book focuses on two eminent psychiatrists who approached these powerful new drugs from a clinical perspective, Canadian Abram Hoffer and the British-born Humphry Osmond, as well as a more enigmatic third figure, psychologist Duncan Blewett, a former soldier whose interest in acid concentrated more upon its spiritual components and its potential for societal renewal.

A recurring theme throughout the story is the group’s struggle to maintain a rigorous and objective scientific standard in their work, a tendency which left them open to easy criticism from their detractors. Barber vividly describes the group’s occasionally cavalier attitude to acid, with experiments that broke down the established separation between patient and practitioner, such as Blewett’s tests which saw both patient and psychiatrist take LSD in each other’s company “in order to increase the empathic bond.” This radical method of therapy proved to be of limited use as, perhaps unsurprisingly, when trialling the approach on two psychiatrists, the researchers found that at the height of the drug experience a “complete block seemed to exist between them while under the drug” and that “neither had any idea of how the other felt”.

Providing further ammunition to critics who claimed that self-experimentation disqualified their work as “sober research”, Blewett and his colleague Nicholas Chwelos had to give up using acid themselves after taking the drug with their patients in 120 sessions. Barber quotes Blewett as saying that the programme’s superiors “had become deeply concerned that we were addicted. We had to knock off taking acid for 6 months before the absence of withdrawal symptoms satisfied our compatriots.”

The situation wasn’t helped by the researchers blurring the line between a professional and a personal interest in LSD, with several walk-on parts for early psychonaut and writer Aldous Huxley, who struck up a friendship with Osmond. In correspondence with Huxley, it was Osmond who coined the term ‘psychedelic’, with the rhyme: “to fathom hell or soar angelic, just take a pinch of psychedelic”. With such imagery and acknowledged self-experimentation, it isn’t hard to see why the scientific mainstream suspected the Saskatchewan team of a conflict of interest. Osmond even became an unwitting hero of the growing counterculture – “See what your word is up to”, Hoffer teased Osmond in a 1967 letter, enclosing a clipping from the Wall Street Journal about the term’s sudden ubiquity.

With the heyday of psychedelic research over by the early sixties, partly thanks to new restrictions on the availability of psychedelics and partly due to a change of government in the province, Barber goes on to chart the often acrimonious battles over the validity of the Saskatchewan research in the sixties and seventies. For Osmond and Hoffer, the charges levelled against their work were often tinged with the suggestion of unprofessionalism and unscientific practice, with the author making a fairly convincing case that regardless of the objective merits of the research, the pair’s work was perceived as threatening the founding tenants of the fledgling new discipline of psychiatry.

Barber declares in his introduction to the book that as a historian it is not his intention “to confirm or deny the scientific validity of the research”, and readers without a scientific background are in the same boat. What the author does do is highlight many of the vested interests and elements of scientific conservatism that prevented Hoffer, Blewett and Osmond’s ideas from receiving a fair hearing. What remains astonishing is that thanks to the near-impossibility of obtaining psychedelic drugs for research, little more is known about the effects of these drugs now than it was half a century ago, although this is slowly changing, in part thanks to the pioneering work of David Nutt and his team at Imperial College London.

Later chapters hint at the reasons behind the downfall of psychedelic research, but mostly through the prism of the work in Saskatchewan. Those after a broader overview of the subject, particularly the impact of psychedelics on popular culture, may wish to look elsewhere. What ‘Psychedelic Revolutionaries’ provides is a detailed look at one area of research, with figures such as Albert Hofmann and Terence McKenna mentioned in passing. Timothy Leary, in his rapid transition from psychedelic provocateur to the Johnny Appleseed of LSD, crops up as a source of frustration to Hoffer and Osmond, who quickly recognised how his flamboyant enthusiasm for the drug would lead to the downfall of their research (even Blewett troubled them in this regard).

Throughout the story, Barber implies that the ineffability of the psychedelic experience has led to a limited acceptance of its medical value among the scientific mainstream. The revelatory nature of psychedelics, especially at the time of their discovery, and their complete break with the nature of any drugs from the past meant that it was inevitable that even the medically-minded Hoffer and Osmond began to talk and write about spirituality and the expansion of consciousness. Blewett’s description of the LSD experience as being “a feeling of some direct contact with the infinite and the eternal, a feeling of being at one with the world’s Author and all His Works” must have incensed colleagues who hadn’t taken the same trip.

The prevailing view among key figures in the story is that it isn’t possible for people without personal experience of psychedelics to understand their effects and possibilities. This is touched on by Osmond, whose primary rule for practitioners using psychedelics in therapy is that: “One should start with oneself.” Barber quotes Osmond’s theory that “unless this is done one cannot expect to make sense of someone else’s communications and consequently the value of the work is greatly reduced.” Although talking specifically about practitioners, this quote sheds light on why the research faced such unrelenting suspicion from the medical establishment.

The lasting impression is one of anger and frustration. Whatever the scientific merits of the research carried out in Saskatchewan half a century ago, it’s clear that with further research psychedelic substances had the potential to enable people to live better, more fulfilling lives. Just looking at alcoholism alone, the number of lives that could have been saved if this line of research hadn’t been suddenly extinguished is incalculable. The moral burden of that lost progress rests on the shoulders of every politician who panders to right-wing populism in office, and then quietly admits to the lunacy of our drug policy when they’re safely ensconced on the backbenches. Books such as Barber’s allow us to learn from both the errors and the unexplored ideas of the past, and shift the conversation on drugs in a more rational and humane direction.

P.W. Barber, Psychedelic Revolutionaries: Three Medical Pioneers, The Fall of Hallucinogenic Research, and the Rise of Big Pharma is forthcoming from Zed Books