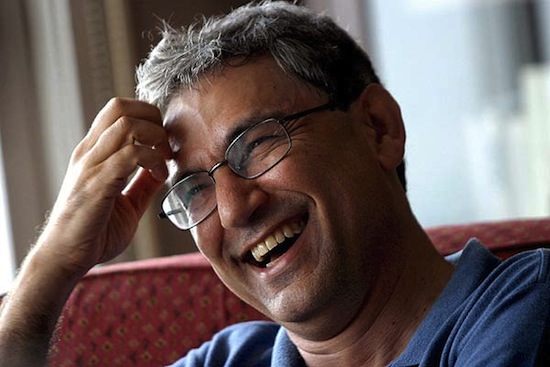

Orhan Pamuk arrives in Bloomsbury carrying Japanese paintbrushes. It’s a crisp autumn afternoon and the 2006 Nobel Literature Laureate has spent the morning shopping for art supplies. “The painter in me has been resurrected,” he says with a playful smile as we settle down to drink strong black tea at his publisher’s office.

Pamuk was born in Istanbul on 7 June 1952. Growing up on the fault line between Europe and the East, the child who would become the most widely-read Turkish writer in history dreamed not of prose, but of painting. His family supported his art and architecture studies and were surprised when, at the age of 23, something changed. “Suddenly a screw was loose in my head and I began to write novels,” he says. “I could never explain why that happened, but it’s an essential fact of my life. My mind is still busy with it. I wrote My Name Is Red to try and understand the joys of painting and Istanbul to try and understand why I did what I did. The Museum Of Innocence also addresses the dead painter in me. The dead painter in me helps the writer in me. They are getting closer. Perhaps I will try to combine pictures with text more often in my books in the future.”

What happened to Pamuk to make his life skip a groove? In The Silent House, the novel which he wrote in 1983 but is now being published for the first time in English, there is a character who “read so many books that he went crazy.” This is an autobiographical nod. He is the boy who read so many books that he went crazy. “Not one particular book, but Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Thomas Mann, Borges, Calvino… these writers and their novels made me. Reading novels changed my life. I’ve said that I mysteriously moved from painting to novels but at that time I was reading so much that it’s really no mystery. Discovering these writers, as Borges once said about reading Dostoevsky for the first time, is like the experience of seeing the sea for the first time in your life. Discovering these writers, all of them, was like seeing the sea for the first time. You’re stuck there. You want to be something like that. You want to belong to that.”

So he put down his paintbrushes and began to write. Actually, the truth is he had already started experimenting with language. At 19 he had some of his poems published in one of Turkey’s leading literary magazines, but he quickly realised he wasn’t born to write poetry. “My little poetic success helped me to move from painting to literature, and gave me some self confidence, but frankly I didn’t believe that I was a poet. Turkey and the Ottoman Empire have a long tradition of poetry. The poet can pose as someone who is possessed by God. He is not a calculating spirit but is frank and honest under the command of a higher being. The poet has a certain status in the culture, while writing novels is a lesser thing. You are a long-distance runner. This distinction still exists. A poet is a saint, a novelist is a clerk.”

Pamuk explores this idea in his novel Snow, which features a poet who hears voices. “This is related to Coleridge’s experiences of writing Kubla Khan,” he explains, “where poetry comes under the influence of God, and also opium perhaps, and then disappears. Poetry is something that you are not doing, but you are possessed by some outer force. It is moving your hand while you watch with amazement.”

Unexpectedly, I’m reminded of Shane MacGowan. I tell Pamuk that The Pogues frontman recently told me in an interview for this website that he believes some of his songs came from a ghost standing behind him and writing for him.

“That is sweet,” Pamuk replies, “It’s a rhetorical thing that makes you relax. To a point I agree with it. All novels have those kind of poetical pages, which later you have to edit and manage, but there are also pages where this kind of poetry doesn’t help. I like surrealistic writing, or what they call automatic writing, but not always. It has to be balanced with a calculating, managing, orchestrating sensibility. I argued in My Name Is Red that Western Civilisation puts artistic creativity on a pedestal. That’s a nice thing. We respect artists. But most of art, I tell you as a novelist, is really craft. I turn around sentences again and again. Yes, there is some artistic element, but lots of craft. Now the poor craftsmen of medieval time are discredited, but all the Picassos and Turners and Coleridges of history were also craftsmen.”

Pamuk spent seven years in the mid-Seventies learning and honing his craft, reading and writing during the days before wrapping up “in two sweaters and an overcoat” to go to the film screenings at the European consulates. There he discovered yet more great storytellers: Orson Welles, Roman Polanski and Wim Wenders. Under all of these influences he published his first novel, Cevdet Bey And His Sons, in 1982 at the age of 30.

The Silent House was his second novel to be published, but the third he had written. He was forced to abandon an “outspoken political novel” he had been working on when there was a military coup in Turkey in 1980. He didn’t think the next book he wrote was political at all, but 29 years on The Silent House seems remarkably prescient about the tensions between the West and the Muslim world which have surfaced over the last three decades.

“It does foresee the future in a sense,” Pamuk agrees. “The character Hasan is an angry and resentful 18-year-old high school student who flunks his classes and goes around with right-wing militants. He collects money from shop owners, terrorizing them. His language of anti-Western resentment is something that everybody knew about in Turkey but nobody cared. That resentment grew and grew. Now it is on the agenda. You can call it ‘political Islam’ or ‘Islamic fundamentalism’, but it’s not necessarily Islam. It could be Hindi or Japanese anti-Western sentiment. The voice of Hasan is based on the confessions of Turkish right-wingers who were arrested after the military coup of 1980. The army not only rounded-up left-wing militants but also some of the right-wingers who had killed people. They were forthcoming in their confessions about what they did but also about their daily lives and political fantasies.”

Has the political landscape changed significantly in the last 29 years?

“Istanbul had changed. My city grew from one million to 14 million. Swallowed by this development was all the Mediterranean flora of fig trees and olive trees, little shantytowns and factories, Ottomans ruins, railroads and hills. The whole landscape has changed, swallowed by high-rises, bigger factories and working-class districts. On the other hand, the problems of modernising Turkey and the ambitions of modernisation, the contradicting resistance and anger, the anti-Western resentment: they’re the same. One more thing changed: the country grew richer, Istanbul is not as frustrated anymore. In the novel, even the upper classes are frustrated. They feel all sorts of inferiority, troubled by their self-image: those angry and resentful voices on the street are fading away because the country is getting richer.”

You’ve said recently that you think the European Union is turning away from Turkey. How concerned are you by that?

“I was eager for Turkey to join the EU, but I understand that the EU has bigger problems now. Enlargement has slowed down as everyone is busy with the Euro problem, which is more than a European problem, it’s a global problem. I’m a bit disappointed about Turkey’s entry, but I’m not crying about it.”

Are you concerned though that Europe’s resistance to admitting Turkey was a product of religious divisions?

“Yes. Europe has every right to ask if Turkey is getting religious or parochial, but also we outsiders who believe in Europe have the right to say that if Europe defines itself not by liberté, égalité, fraternité, but by Christianity or ethnicity then it is going to end up just like Turkey too. If your definition of Europe is based on religion then yes, Turkey has no part in it, but if it’s something else, like liberté, égalité, fraternité, then once Turkey satisfies these criteria it should have a place.”

As he’s mentioned, parts of The Silent House are drawn from his memories of being a young man in Istanbul, and I ask him if there was a certain nostalgic melancholy that came from revisiting the work during the process of translation: “No. I’m happy that the whole nation got rid of this frustrating sense that nothing was happening, and stopped killing each other. Don’t forget that the book describes an Istanbul of the late 1970s and early 1980s where left wing militants and right wing militants were seriously shooting each other. If you read the wrong newspaper in the wrong neighbourhood you could get shot. So I’m not nostalgic about that period, but I may be nostalgic about the old streets of Istanbul. This is not about that. This is about the intensity of living in a country where the expectation of unhappiness is so intense.”

If you could speak to yourself in 1983, would you give yourself any advice?

“I would say to myself: don’t make the ending that tragic. I would definitely say that. I may be wrong, but I would make the picture broader and the book longer, adding more characters, but the rest I’m happy with. I’m happy that I did not give too much prominence to inner monologue or stream-of-consciousness, as other people did at that time. It’s balanced. I’d argue that there’s no such thing as inner monologue. It’s really inner dialogue. We don’t talk just to ourselves, we talk to some real or imaginary person or maybe something that somebody said 20 years ago, but there is another text to think against and other beings. It’s a literary concept, but actually inner monologue, I argue, is inner dialogue. You always answer someone in your mind.”

This statement strikes me as startlingly lucid, the sort of keen observation which makes Pamuk such an enthralling and humane writer. There are many reasons to love his books. He is wise and kind and treats his characters with empathy, but perhaps more than anything what brings me back to his novels is the elegiac ocean of melancholy which dwells within them. In his 2003 memoir Istanbul: Memories Of A City, he dedicates a chapter to Turkish melancholy: hüzün.

“I asked myself what feeling does Istanbul evoke in me? The obvious answer, not just in me but in everyone in Turkish poetry and music, is hüzün. Istanbul was my autobiography until the age of 23. It ends in 1974. The young generation of Turkish readers said: ‘No, our Istanbul is not black and white and melancholy. It’s a happy, colourful place.’ They were right, and today they would be even more right. The economic boom made the city, at least its historical and touristy parts, a very colourful and happy place. However, that historical and touristy Istanbul is not the only Istanbul. There remain 13 million people who are living in the peripheries in the working class districts. Go to those places in winter and again you will find the melancholy I mention in Istanbul.”

Are you still trying to capture that in your work?

“My Istanbul book, The Museum Of Innocence and The Innocence Of Objects have the same sentiment. That this city was provincial, that it generated sadness and inwardness not in individuals but in the whole community, but as I say it is changing now.”

But can economic changes really do anything about the underlying melancholy?

“Hüzün also has communal ethical and moral dimensions that can be compared to what an American scholar said about Japanese culture: ‘the nobility of failure’. Hüzün advises you: don’t venture too much, you’re not going to succeed. Be modest. Don’t be individualistic or capitalistic but belong to the community. I respect some of these sentiments, but it is also sometimes important to have the creativity of the solitary artist. Hüzün advises too much to respect the elders or establishment. That melancholy has a negative medieval side to it. A terror of being yourself. It tells you to belong to the community, just don’t be distinct. Be like others. Some of these ideas may work in pre-modernity,” he laughs, “but I don’t like them.”

Is hüzün related to the existential terror of death?

“No, belonging to a community doesn’t avoid the idea of death, really,” he laughs again. “Fear of death, all the anxieties about that… maybe that fear is not around in me. Maybe it will come to me, but I don’t think of it too much. In my youth, say, reading Albert Camus: “The greatest philosophical question is whether to commit suicide or not.” I loved these questions as a teenager, but not as someone worrying about the other world or what will happen to me. Maybe that will come. Now in my mind I’m not as busy with teenage metaphysics. Maybe my paintings are a bit, but I’ve changed. Now I think of death as a very natural ending. I hope it happens naturally, but my mind is not busy with death. I am busy with the novels that I will write. Yes, of course I should have characters whose minds are busy with it, but I have acknowledged death. Maybe because of the likes of Camus or Dostoevsky and that sort of existential thinking in my early twenties. It is not news for me. I’m not worried about it, but perhaps I will begin worrying as it gets closer.”

In 2006 Pamuk had just started teaching at Columbia University in New York and was working on his next novel, The Museum Of Innocence. One morning, at seven am, he received a phone call to tell him he had won the Nobel Prize. “My automatic reaction was to say: “This will not change my life!” The words came out of me in a hurry, in a panic. That is the cliché about the prize. As a writer, it didn’t change me. I continued the novel I was in the middle of. I was lucky, because I didn’t have to say: ‘Oh, what am I going to do now? What is my next project?’ I was deeply buried in a project that I could continue. However, it did change my life in many ways. It made me more of a diplomat of Turkey, with more political responsibilities and pressures. Everyone is watching, so you cannot be playful or silly or irresponsible. I am doing my best to keep the irresponsible, playful child in me alive. This is the one who helps me write my books and find new ideas. That is what I have to protect above the formality or snobbishness the prize may give you.”

Do you think of yourself as the voice of a generation?

“I’d prefer that to be ‘voice of a nation’. Inevitably, you represent both your nation and generation. From the visitors to the Museum of Innocence, I know that they tell me they had the same things in Spain, and Italy, and Iran. That immediately places you in your generation, but of course we all write to address something beyond our generation. The problem about being a famous Nobel Prize winner, particularly as there are not many other high-profile Turkish intellectuals, is that the burden of both explaining the country to the world and addressing political issues is sometimes too much.”

That next novel, The Museum of Innocence, became one of Pamuk’s greatest projects and helped to resurrect the painter within him. “The Museum of Innocence is a novel about love that doesn’t put love on a pedestal. It treats it as a more human thing, something like a car accident that happens to all of us. We all behave the same. All the negotiations with the lover: anger, resentment, impatience and so on. In the story, the upper class spoiled man collects the things that his beloved touches, and after the sad ending he wants to exhibit these objects and even tells us how to make the museum. Four years after I published the book in Turkey I created the museum, and opened it this April in Istanbul. Both the novel and the museum were conceived together. It’s not that I had a successful selling novel and then wanted to illustrate it. They are telling the same story. When I opened it the welcome from the Turkish media was very sweet, which was surprising but I was very happy. We have a good number of visitors. In 2011 I did not write as much in the last six months as I had been for the last 38 years. I quit writing fiction and gave all of my energy to the eleven or twelve artists, carpenters, friends and assistants who were working together. That was a really great time. The painter in me was so happy, but so was the writer in me. Now that period is over I’ve returned to my old self. Empty page. Discipline. Working all the time. Which I like.”

Have do you feel when you face the blank page?

“No problem. I never have what Americans call ‘writer’s block’. Perhaps it’s because I plan ahead, and if I do feel blocked I can move to another chapter. Perhaps it’s because I’m optimistic. If I know what I’m going to write, and I always prepare that the night before, then a blank page gives me not anxiety but freedom. The freedom of creativity and being alive.”

Thomas Mann said that writers are people for whom writing is more difficult than other people. Do you agree?

“Writing is always difficult, but you have your rewards too. You are writing something that nobody else has done. Even a little detail, if no-one else has done it then you’re happy. It’s your invention. There is that kind of happiness. Writing is difficult, but it’s also rewarding. If you’re happy with what you do then you smile all night. Sometimes you can’t. Then I’m sulking and my daughter says to me: “You didn’t write well today, is that it?””

Do you enjoy holding court in public?

“I didn’t. I’m not a good party person, especially when I was a teenager. I was not good at parties. That is represented in The Silent House, there is lots of nervousness and inner dialogue going on. I learned to do it because of the success of my books, learning to introduce and read from them. Contrary to my youthful days I now enjoy listening to other people talk. In my youth, just like the characters Hasan and Metin, I tried to prove myself. That has changed, and I’m not complaining!”

I asked that because I was wondering if you consider yourself a natural storyteller?

“No, I don’t. I’m a modern novelist and a modern novelist should perhaps occasionally, like Albert Camus in L’Etranger, be a natural storyteller, but most of it is planning, making decisions even before you start to write. I’m also a photographer. You don’t mind, right?”

While he was speaking Pamuk has taken his digital camera out of his jacket pocket, and has crooked his arm over his shoulder so that he can photograph himself with me in the back of the shot. The phrase ‘MySpace pose’ flashes across my mind. I tell him I don’t mind as long as he takes one for me as well. He does.

From the look on Pamuk’s face I get the impression that the “irresponsible, playful child” within him is at work, so I ask him to tell me a joke. He thinks for a moment, then says: “This comes from life, and it’s about a subject that I deal with in my books: sibling rivalry. I used to exchange letters with my brother full of this rivalry. Eventually I wrote to him: ‘Look, the two of us have wasted a lot of energy on resentment. Now that we’re going to university, we should forget this competition between us. He wrote back: ‘Yes, you’re right… but I observed it first.’”

He smiles at the memory. “I like these oxymoronic jokes and self-contradictory observations. It is like the guys, and I come across a lot of them in Turkey, who say that they are ‘probably the most modest person in the world.’ They are proud of their modesty, and say: ‘I’m very, very modest. Perhaps you didn’t notice it. There’s nobody more modest than I am.’”

What are you proudest of?

“I’m happy that I did not waste much time in life. I’m happy that I did not spend too much time hanging out with the boys, that I locked myself up. I was partly like Metin, my character who wants upper-class mobility or some success and wants to try and prove his intellect. Perhaps I did that, but only through writing books, not through other venues like business. I’m proud of the fact that although this or that happened I never left writing. I continued to write and from the age of 23 I’ve never stopped. Through hard times, political and personal problems, I wrote my novels. The experience of writing a novel is the experience of looking at the world through other’s windows, from other points of view. This teaches you a sort of humility if you do it for almost 40 years. I’m proud of that humility, if I have it. I hope I have it.”

I can’t resist telling him that being proud of his humility sounds like one of his oxymoronic jokes.

He laughs. “Yes, another joke! Another contradiction!”

Have your writing habits changed since you started at 23?

“No, I still handwrite with a fountain pen into squared notebooks.”

Why squared?

He shrugs. “I don’t know. I’m used to it. It’s just easier. The comfort of it. Probably I am working more now. I’m more careful not to waste time. I plan out more, because if you don’t plan then you’ll waste a lot of time, but the rest is the same thing. Sitting at the table in the morning, and if you know what you’re going to do that day then you’re the happiest person alive.”

His playful smile is back. “I’m still like that.”

Silent House is available now on Faber & Faber

Follow @theQuietusBooks on Twitter for more