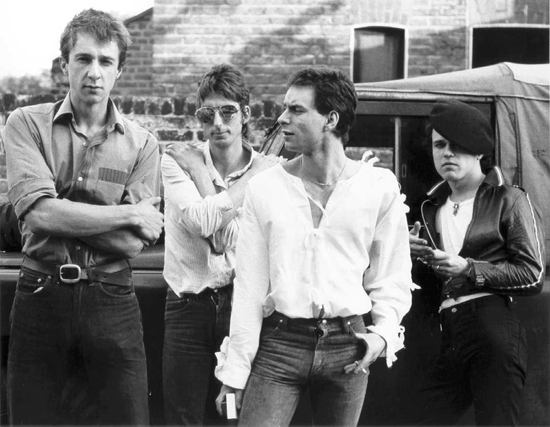

Continuum’s 33 1/3 series offers an excellent opportunity to explore the stories behind albums outside of genre round-ups. Wilson Neate’s forthcoming book on Wire’s Pink Flag is a superb addition to the series. Neate interviews all four members of Wire (and gets told to clear off by fifth member and founder George Gill) along with the likes of Glen Matlock, Jon Savage, Steve Albini, and Graham Coxon. In this extract, he looks at the early days of Wire’s emergence onto the dying embers of the London punk scene

By the time Wire debuted as a quartet at the Roxy on April 1, 1977, British punk’s seminal events had taken place, its most creative phase was over and it was a tabloid staple. In summer 1976, Wire had been inspired by punk’s early rumblings, excited by the space and access this cultural revolution promised. "This was something that one had to be paying attention to," asserts Colin Newman, while Bruce Gilbert was guardedly intrigued ("I was less excitable"). Wire shared punk’s general consensus that music had become stagnant, a closed corporate shop, open only to those displaying musicianship or meeting the labels’ short-sighted notions of commercial viability. Punk seemed fresh and democratic since anyone could get involved: "There was excitement about a new type of music," remembers Robert Grey. "Punk was the biggest influence at the time, and with our musical abilities, what other

options did we have? I certainly couldn’t say I was a musician." Gilbert agrees: "The idea that there was a new way of making

music which meant you didn’t have to learn, say, 400 songs seemed very attractive."

The nascent Wire had been caught up in the initial excitement. The bandmembers and their eventual producer saw the Sex Pistols and others at the 100 Club on September 20, 1976. This was "something unique," according to Grey, who recalls a clear sense that "something was happening." Gilbert, too, was a willing participant. He appreciated early punk gigs as vibrant spaces where the audience contributed to the rich, dynamic canvas as much as the performers: "I viewed it as a bit of a laboratory, not musically but culturally, because the people were experimenting with themselves: with their behaviour, their appearance and their clothes. Everything was up for grabs."

Nevertheless, Wire’s maiden gigs (still with George Gill) in December 1976 at the Nashville Rooms and St Martins School of Art didn’t augur success. Their first performance was denounced by the singer of R&B headliners the Derelicts (Susan Gogan) as "the death throes of cock rock," laughs Grey. The meagre audience remained apathetic. At St Martins, the students pulled the plugs on them. As Gilbert explains, "The audience for this kind of thing hadn’t really developed. They were still expecting pub rock." Newman soon saw more encouraging signs when Wire played at the Royal College of Art: "Somebody smashed up a chair. I think that was Shane MacGowan. The smashing up of the chair was meant to be telling us how good we were because, obviously, that’s what you do."

Wire’s similarities to the other new groups gigging around London in 1977 were superficial: they witnessed punk’s foundational moments; they had short hair and straight trousers; they played venues where punk bands performed; their songs were short, fast and noisy; they played the usual instruments, not entirely competently, and they had an intimidating live presence. They even briefly had punk aliases: Newman was Klive Nice (in contrast with Johnny Rotten), Lewis was Hornsey Transfer (a more abstruse pseudonym referencing his art-school background, nomadism and love of football). However, Wire’s differences were more striking, as hournalists noted almost immediately. "No Pun(k)s Please, We’re Wire" proclaimed their first NME cover in December 1977. Wire weren’t like the other punks: they shared some of the vocabulary but spoke another language.

Also, Wire didn’t join any cliques. "They were always outside of everybody," remarks writer Jon Savage. "They weren’t matey with the main players. They weren’t keyed into the groups around the Clash and the Sex Pistols, the punk inner circle. They were always quite separate." Looking back, ex-Sounds journalist Pete Silverton paints a depressing picture, specifically of the Sex Pistols’ orbit: "The snobbish attitude within punk was extraordinary— and it changed day to day. It was like a medieval court at which Johnny Rotten presided, where people were in and out on the whim of the king. It was pathetically antithetical to its supposed ideology. For a supposedly egalitarian, revolutionary movement, punk made more judgements on smaller points of etiquette and trouser finish than the Court of Versailles." This environment held no interest for Wire.

Wire stood apart, a self-contained unit. As Graham Lewis told Melody Maker’s Ian Birch in December 1977, "We felt an affinity but we weren’t part of the social scene." Looking back, Grey agrees: "Although we were playing in a punk arena, we did try to separate ourselves from the rest of the bands." Cally Callomon noticed Wire’s insular nature, his abiding memory of the band encapsulating their self-reliance: "They travelled around in a Land Rover pulling a trailer. They weren’t part of the scene. They didn’t hang out. They didn’t make friends. They came across almost like a straight-edge group. I think people found that quite hostile." Keith Cameron’s summation of Wire for a 2006 Mojo retrospective is more succinct: "No guitar solos, no clichés, no mates."

Lewis’s comically brief recollections of fellow musicians illustrate that lack of kinship. He once politely asked Rat Scabies to extinguish a discarded cigarette for him, only to be accused of trying to "out-punk" the Damned’s drummer. His interaction with the Clash was equally substantive. Before a gig, Joe Strummer looked up from a Bruce Lee biography to ask Lewis if he’d heard of the martial artist. Lewis said yes, and Strummer continued reading. Newman has similar memories: "One of the Clash may have said hello to me, and once George Gill told Rat Scabies to get on his bike." Ironically, Scabies recalls Wire fondly: "They used to come down and see us play at the Hope & Anchor and tell us they were better than we were, in a very obnoxious, drunken manner—but we loved Wire, so we didn’t mind."

(During the anti-monarchist days of 1977, Wire would certainly have been ostracised by London’s punk elite, had it been known that Newman once met the Queen. In mitigation, he notes that the occasion was an official visit to his school, attendance was mandatory and he was mistakenly introduced to Her Majesty as Paul Newman.)

Age also contributed to Wire’s isolation in punk’s superficial milieu, inevitably colouring perceptions: in 1977 Gilbert was 31, Grey 26, Lewis 24, Newman 23—and in a youth subculture privileging image, street cred and rebelliousness, a couple of years’ difference can be crucial. "They were a bit older," Savage points out. "They weren’t completely adolescent, and they weren’t

pathetic."

Pink Flag _by Wilson Neate is published by Continuum on April 30th in the UK, and is already on sale in the USA. Order a copy here.